The Tragic Truth About The Highway Of Tears

Cold cases aren't exactly unheard of. Far from it, really. Anyone who's seen a few episodes of a police procedural can probably think of a time that a cold case has made for a juicy hour of television. Obviously, the details would be embellished in a fictional story, but the basic idea of what a cold case is — that's not entirely wrong.

Missing persons cases or homicides go unsolved at the time they're reported, and sometimes they just remain unsolved years later. It's always a tragedy, no matter the details of the case. But when dozens — maybe hundreds — of cases go unsolved, all seemingly connected by the area in which they happen, then it's an incredibly tragic trend, one which leaves so many families in mourning and without closure. And if there's another factor connecting all of those cases, tying them all to decades of social injustice and discrimination? Then, there's something much deeper plaguing society, a tragedy very different than random killings and kidnappings, and one that can eventually lead to the existence of places like Canada's Highway of Tears.

Where is the Highway of Tears, exactly?

True to its name, the Highway of Tears does, for the most part, refer to a literal highway, according to the Canadian Encyclopedia. Tucked away in the northern part of British Columbia, Canada, lies Highway 16, with a 450-mile stretch of its full length constituting the actual Highway of Tears. At one end of the highway is the city of Prince Rupert, while Prince George sits at the opposite end.

However, these two cities aren't really the important part of this story. Far from it. Instead, the terrible truth lies in the area between them. That's because along that expansive stretch of land, many First Nations — the homes of various Aboriginal groups — border the highway. Largely cut off from the rest of the country due to poverty and the general remoteness of the geography, the struggles faced by the Indigenous people of Canada are what truly give this highway its tragic name.

The Highway of Tears is not just a normal highway

Those struggles faced by the Indigenous people are numerous, but in this case, it really comes down to the fact that the Highway of Tears is an area that is marked by tragedy of a pretty specific kind. It's basically an enormous zone where women — most of them Indigenous women — have mysteriously vanished. Some of them are found murdered, sometimes months or years after their disappearance, while others are never heard from again (via the Canadian Encyclopedia).

Officially, 40 different cases have been linked to the Highway of Tears, spanning multiple decades, from 1969 to 2006. But, in reality, that number could be much higher. Looking beyond that exact time range, some cases — considered unofficially linked to the highway — are as recent as 2014, adding nearly another decade's worth of tragedy to the already long list. The same can be done with the geography, with Indigenous groups claiming that the true number of victims far exceeds 40, were the officially recognized boundary of the Highway of Tears to be extended. Regardless of the exact status of the cases, whether official or not, most of them remain unsolved.

Hitchhiking is an unsafe necessity on the Highway of Tears

Now, it might seem strange to specify hitchhiking in particular as a risky behavior. Of course, it is a potentially dangerous practice in general, but it's also not an uncommon one when it comes to the Highway of Tears cases. According to Jessica McDiarmid in her novel Highway of Tears: A True Story of Racism, Indifference, and the Pursuit of Justice for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, going back to the 1970s, the practice was commonplace, especially in that area. People at the time just didn't have a way to get around, and teenagers would usually hitchhike to get to events or see their friends living in the next town over. Everyone did it, and that could've provided killers and kidnappers the opportunity to add another name to the list of the Highway of Tears' victims.

But that's still true, even now. According to CBC News, professor Jacqueline Holler launched a study on hitchhiking habits in 2012, which ultimately proved a few things. While some people did simply prefer hitchhiking, others did it out of necessity, with this particular area of northern British Columbia having very few of its transportation needs met via other sources. And a large number of the people who hitchhike are Indigenous, likely because they can't afford their own transportation, despite living in these remote areas.

The creation of E-Pana

Fortunately, it's not like the Canadian government has done nothing to try and address this problem, with the year 2005 seeing the creation of an organization called E-Pana. With a name derived from an Inuit word for a spirit goddess (specifically, one who watches over the souls of the recently deceased), Project E-Pana was made with the intention of investigating and solving the disappearances taking place along the Highway of Tears. Granted, they aren't actively looking into every potentially related case. Instead, they currently recognize only 18 of those many cases, 13 of which are homicides, while the remaining five are missing persons cases.

It's a relatively short list that comes from a fairly strict set of guidelines. All 18 of their cases involve female victims who were involved in some form of high-risk behavior at their time of disappearance, such as hitchhiking. Beyond that, all 18 victims were last seen within one mile of the Highway of Tears, which includes Highway 16, Highway 97, and Highway 5, in this case.

Race plays a part in all of this

The fact that Indigenous people live in communities impoverished enough that hitchhiking becomes a necessity really points to race as being the true tragedy, here. When it comes to the Highway of Tears cases, many of the victims are Indigenous women, including ten of the 18 officially recognized by E-Pana. That's not just a coincidence, and sadly, race is also probably at least part of the reason why these cases have been handled in the way that they have. After all, E-Pana wasn't founded until over three decades since the earliest disappearance. Before that, families of victims would cite police indifference regarding Indigenous girls, writes Jessica McDiarmid in her book. Rather than seeing an official investigation conducted, the families would have to conduct their own searches and raise their own funds to do so, while authorities would write off the disappearances in a way that painted it as the victim's fault — drinking, sex work, or consenting to sex.

With that in mind, it's really not that hard to imagine why so many cases went unsolved. That's not helped by the lack of visibility that the Highway of Tears and its victims had, at least until the 2002 disappearance of Nicole Hoar, a 25-year-old white woman. Her case was the one which brought the Highway of Tears to social media and larger news outlets, but her race is, again, probably not a coincidence and points to a pretty ugly side of society.

The Highway of Tears speaks to a larger issue

The truth of the matter is that the Highway of Tears and its long list of tragedies is ultimately a symptom of a much larger and more widespread problem. Indigenous people have been forced to deal with systematic racism for years — and in more direct, violent ways than police indifference surrounding missing persons cases. They've been forcibly assimilated into mainstream, white society, and a 2014 film titled The Highway of Tears shines a light on one of the ways this has been done.

Namely, it's a school system. A mandatory one, made to indoctrinate thousands of Indigenous children into mainstream culture and which reads more like a prison than a school. Taken from their parents, kids were forced into these schools, during which they weren't allowed to see their families and communities, speak their native language, or otherwise interact with their native culture. Honestly, there isn't much that needs to be said here about why this was a problem. A 2019 report, summarized by CBC News regarding the Highway of Tears cases and the treatment of Aboriginal women in general probably puts it the best, likening it to a genocide.

Systematic racism has been a long-time problem for Indigenous people

The situation on the Highway of Tears — even that of the residential school system — is really just underpinned by a long history of racism. The report, Indigenous Experiences with Racism and its Impacts, shines a light on that terrible history, going back to the settlement of British Columbia in the 1700s, when bounties were offered for the scalps of Indigenous people.

And the blatant acts of violence aren't just historical. Even well into the 2000s, Indigenous people (particularly women) have faced higher rates of violence compared to their non-Indigenous counterparts. But this violent racism also laid the groundwork for more systematic racism.

In 1876, the Indian Act was created by the Canadian government — an act which claimed to protect Indigenous people and their rights but really created federal organizations that could exert control over those rights. It was an ultimately racist policy, which only sprouted further discrimination. Some people saw the Indian Act as a problem, thus, their solution would be to eliminate Indigenous people entirely and absorb them into mainstream society in order to render the act unnecessary. Again, the problem there is pretty obvious.

Racism against Indigenous people has been present for a long time, rearing its ugly head in many forms — blatant violence, discriminatory policies, underfunded "Indian reserves," and schools meant to strip children of their native culture. The Highway of Tears is, in the end, another form of that problem.

Email Scandal

Knowing the racial factor in these Highway of Tears cases, as well as the incidence of long-standing racism, any other scandals then start looking particularly suspect. In 2015, reports came out regarding an email scandal within the government (via The Globe and Mail). An assistant to the transportation minister was asked to look into and retrieve information on the Highway of Tears, only for another colleague to arrive and "triple delete" all of the relevant files. Of course, that colleague denied doing such a thing but also resigned shortly after the incident (and then was convicted a year later for lying about his involvement).

To make things look even worse, CBC News later revealed that the scandal took place shortly after officials had spoken to a number of First Nations regarding transportation issues. While some of those meetings were cited as being productive, reports and correspondence didn't exactly make it back to those communities, with officials claiming that they had no records related to the topic. With the email scandal occurring around the same time, it's not hard to see why Indigenous people have doubts as to how the government is choosing to handle their issues.

Solved Cases - Colleen MacMillan

At the very least, despite scandal and deeply rooted societal issues, there are the occasional spots of hope when it comes to the cases linked to the Highway of Tears. All is not lost in these cold cases, with more recent investigations finally finding solutions. CBS News reported on the investigation regarding Colleen MacMillan, a 16 year old who disappeared in 1974, only for her remains to be found a month later.

Investigators at the time found her blouse and made the choice to keep the evidence — a smart move in the long term, because DNA samples were found on it. As DNA testing became more prevalent in investigative work, those samples were given a second look and entered into a database. There weren't any exact matches to it, but it was confirmed to belong to an unidentified male.

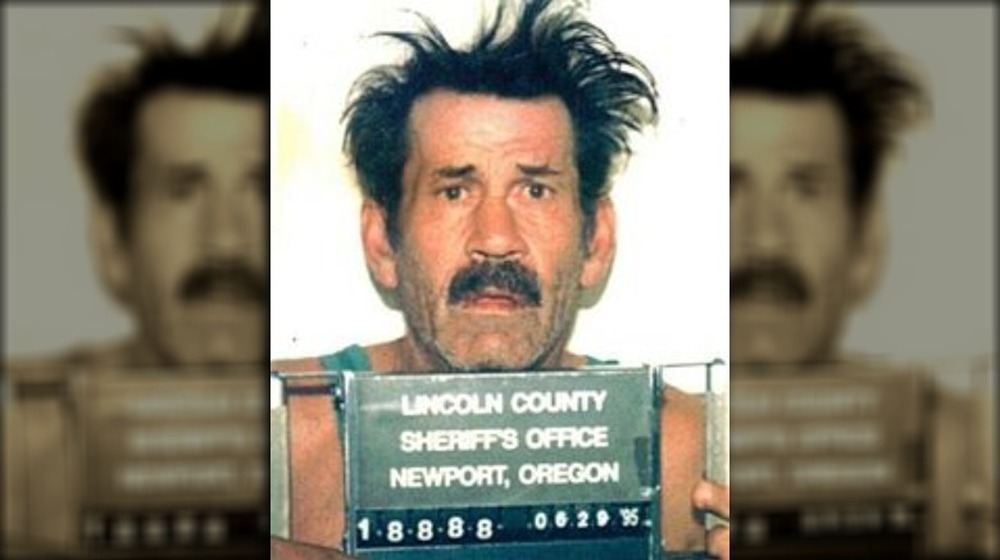

Fast forward a few more years and a few more scientific advancements, and more sophisticated analysis alongside the resources of Interpol returned a match for the DNA sample — Bobby Jack Fowler, an American criminal who had been working in Canada in the 1970s. In 2012, he was officially connected to MacMillan's murder, with the ensuing investigation also connecting him to two other unsolved Highway of Tears cases — those of Pamela Darlington and Gale Weys — albeit only circumstantially.

Fowler was also a suspect in the murders of 20 other people across the U.S. and Canada. According to the Huffington Post, he was imprisoned in 1996 for kidnapping, attempted sexual assault, and assault. He died in 2006, while still incarcerated.

Solved Cases - Monica Jack

Colleen MacMillan's case, while being one of very few solved cases, isn't alone in that regard. Reported on in 2018 by Global News, Garry Taylor Handlen was put on trial for the murder of Monica Jack, a 12 year old who went missing in the late 1970s, and whose body wasn't found until 1995 — a full 17 years after her initial disappearance. With a backlog of sexual assault charges, Handlen had already been a suspect in the case in the past, though he was never charged.

But that changed in 2014 with the start of an undercover sting operation, which put Handlen into contact with a fake crime organization and an equally fake crime boss, who informed him that he was being investigated for the murder of Monica Jack. In the process, Handlen confessed to the undercover officers, showing them where he'd kidnapped her, and explained the rather disturbing details of her murder. A separate sting operation also led to his confession regarding the case of Kathryn Mary Herbert (though that evidence was ultimately deemed inadmissible and the charges were dropped).

In the end, CTV News reported that he was convicted in early 2019, guilty of first-degree murder and given a life sentence.

Highway of Tears symposium calls for change

Aside from the answers to a few Highway of Tears cases, there have also been efforts made to bring about much wider change. A report detailing the work of a 2006 symposium (called the Highway of Tears Symposium Recommendations Report) opened with a recount of a walk that took place a year earlier, made in memory of the many victims and in honor of their families.

The report then went on to explain a fairly detailed plan to prevent the tragedies that lead to such memorials, providing specific goals, both long- and short-term. Of course, victim prevention was one of those, with the symposium report explaining that prevention could be attained by protecting hitchhikers or by eliminating the social conditions — like poverty — which continue to encourage the practice.

Other systems were recommended, too, in order to bridge the gap between officials and the Indigenous people. Support systems and counseling for the families of victims would hopefully allow for a greater amount of trust between the two groups, while a better system of communication would allow for a long-standing relationship, rather than one which only exists in times of tragedy.

Thirty-three specific recommendations were made, with some of them coming to fruition. Carrier Sekani Family Services made Aboriginal counselors available for families of victims as of 2006, and BC Government News reported that webcams were being installed along Highway 16 in 2018, an alternate take on the patrols that the symposium recommended.

Bus services for the Highway of Tears

In that same vein, the government has also taken some further strides in terms of problems surrounding the Highway of Tears, and the Canadian Encyclopedia documents those efforts. On the hitchhiking front, in 2017, BC Transit created three new bus lines that would service different areas of Highway 16. Granted, the recommendation was first made in the aforementioned 2006 symposium report, but it did eventually come to fruition, with over 5,000 people using the new bus lines within the first year.

Less fortunately, Greyhound Canada announced that it would stop servicing the Highway of Tears in 2018. The BC Transit lines would remain running regardless, though the local minister of transportation openly recognized that they don't make up for Greyhound's services and made a general promise to work with those affected. It's not a perfect solution, and one which, honestly, could — and probably should — have been implemented far earlier. But at least it's better than hitchhiking.

Inquiry Into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women

On the social justice front, August of 2016 saw the formation of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls — the MMIWG inquiry, for short. As described by the Canadian Encyclopedia, this inquiry was granted nearly $54 million in funding over the course of two years, with the task of finding solutions for lowering the rate of violence directed toward Indigenous girls, as well as doing away with systematic racism.

The MMIWG inquiry held many meetings with various communities and listened to thousands of testimonies over the course of the next three years, finally delivering their 1,200-page report in 2019. In it, they made recommendations — or, rather, "legal imperatives," according to the chief commissioner of the inquiry — including the appointment of more Indigenous judges or police officers in order to promote more equitable legal practices and to keep cases like those linked to the Highway of Tears from being swept under the rug (via CBC News).