The Tragic Explanation Of The Day The Music Died

The Day the Music Died was Feb. 3, 1959. That was the morning that a small chartered plane crashed in a cornfield in Iowa and killed three of rock n' roll's biggest and brightest upcoming stars. All three had only recently kicked open the door to stardom, and in spite of their relatively short careers, they left an undeniable mark on the world of music. What they may have done, had they lived, is unimaginable.

It was an earth-shattering end to the decade that Rolling Stone calls "A Decade of Music That Changed the World," and it absolutely did. Rock may have been born in the 40s, but it was in the 50s that it grew up, learned to dance and drink, and decided it was going to be something completely different. Rolling Stone also calls it "a sonic cataclysm," and it was that, too.

The decade was headlined by guys like Chuck Berry and Little Richard, Fats Domino, Jerry Lee Lewis, and — of course — Elvis. But 1959 kicked off at a crossroads, with the loss of Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and the Big Bopper. In the end, though, one of Holly's own songs summed up their impact on music — they would "Not Fade Away."

Who did the world lose on The Day the Music Died?

On Feb. 3, 1959, a chartered plane left Clear Lake, Iowa, and headed for the nearby Moorhead, Minn. The pilot was 21-year-old Roger Peterson, and according to Biography, he had no idea there was a severe weather warning in place when he took off with his passengers.

Buddy Holly was just 22 years old at the time, but he'd been performing since he was 16. He was a regular on his local radio station when he was in high school, and things seriously took off when, in 1955, he opened for Elvis. Just two years later, he and his band — Buddy Holly and The Crickets — scored a hit with "That'll Be The Day." Over the next year, they had a whopping seven Top 40 singles, and the world, as they say, was his oyster.

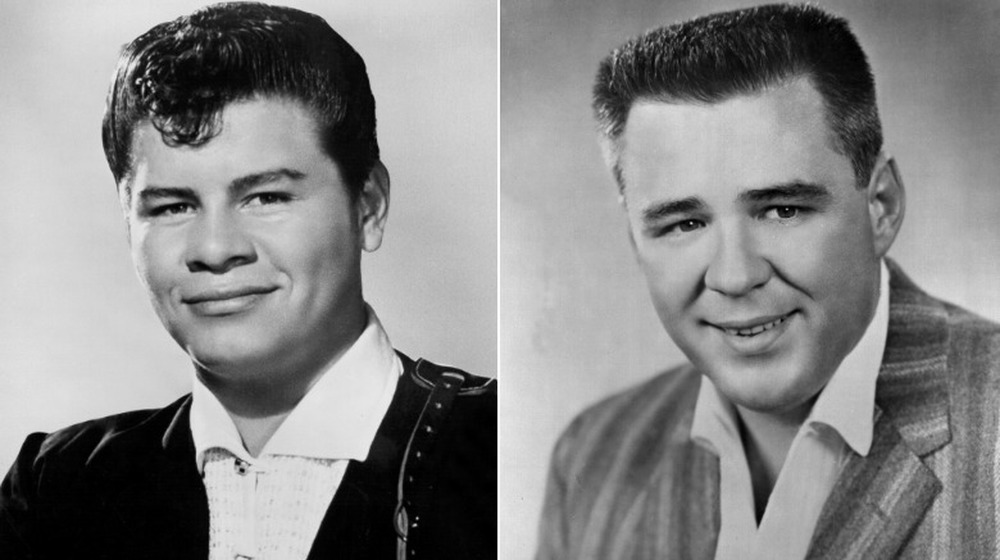

Ritchie Valens (left) was just 17 years old, but he was already known as rock's first Latino headliner. He'd hit it big with "La Bamba," "Donna," and "Come On, Let's Go," which is even more impressive considering he'd only joined his first band just a year before.

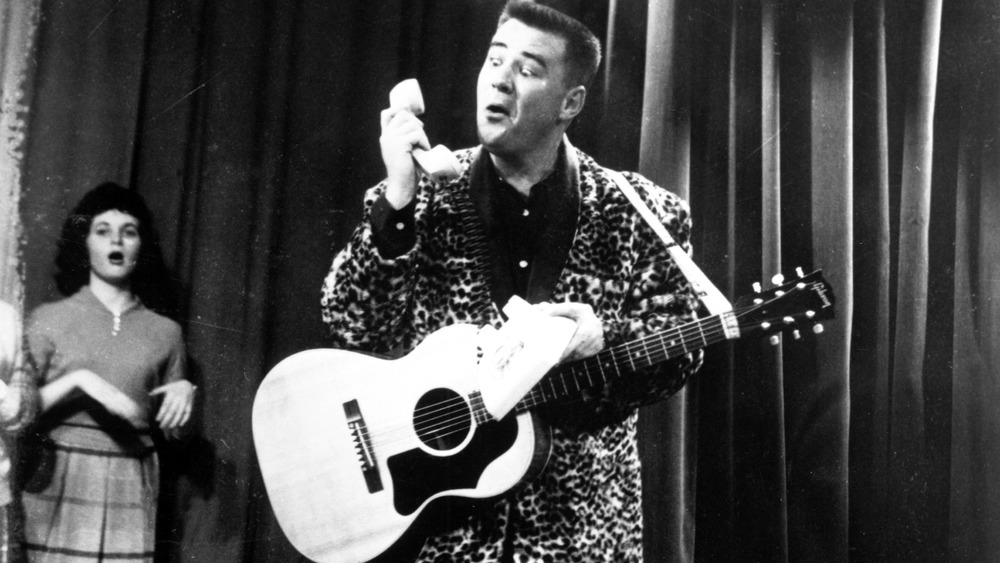

And then there was J.P. Richardson (right), a Texas native like Holly. He, says Bullock Museum, got his start — and moniker — as a DJ in Beaumont, Texas. A songwriter and performer, he had his own hit with "Chantilly Lace" and — having written several other number one hits of 1959 — ended up on the fateful tour.

The Winter Dance Party Tour was a nightmare from the start

In 1959, Buddy Holly had big plans. After an amicable split from The Crickets (and a less-than-amicable fight with his producer over royalties), Texas Monthly says he was planning on starting his own record label, his own publishing company, and his own studio. He was short on cash, though, so he signed on with the Winter Dance Tour, a grueling concert tour that haphazardly crisscrossed the Midwest.

It's not an exaggeration to say it was cursed from the start. It was mid-winter, and the performers traveled in old, retired school buses that had a tendency to break down during the drive from one gig to the next — which were usually hundreds of miles apart.

On January 31, Holly and his band were headed across Wisconsin when their bus froze and left them stranded in howling winds and 30-below-degree temperatures. According to the Star Tribune, they burned newspapers in an attempt to keep warm, and it didn't work — Holly's drummer ended up with frostbite. It wasn't the first time misery descended, either, and Holly historian Bill Griggs says, "The tour from hell — that's what they named it — and it's not a bad name."

In 1999, John Mueller and his Buddy Holly tribute band tried to recreate the 24-city, three-week-long (via the Star Tribune) tour. It was so grueling that by the time they got to the fateful gig, Mueller had lost not only his voice, but 15 pounds.

An ill-fated decision to alleviate some pain

After the group was rescued from the freezing cold and their equally frozen bus, drummer Carl Bunch was hospitalized with frostbite. The rest went on to Hurley, Wisc., and from there it was on to Green Bay, then Appleton for a show that had been canceled. The next day was supposed to be an off day, but they got word that they'd had a date added in Clear Lake, Iowa — 355 miles away.

According to the Star Tribune, Clear Lake was the point where Buddy Holly — and everyone else — had enough.

While they were setting up for the Clear Lake show, Holly chartered a plane from Dwyer Flying Service. Texas Monthly says it cost $108 for the plane and pilot, and after the end of the gig — and a round of autograph signing — the group headed off. Roger Peterson, the pilot, had promised to file a flight plan from the air but never made contact.

The 1947 Beechcraft Bonanza hit the ground about five miles outside of Clear Lake, skidded around 500 feet, and much of it disintegrated on impact. The remains of the pilot were later found inside, and This Day in Music says the three musicians had been thrown clear but died instantly.

Be careful what you ask for

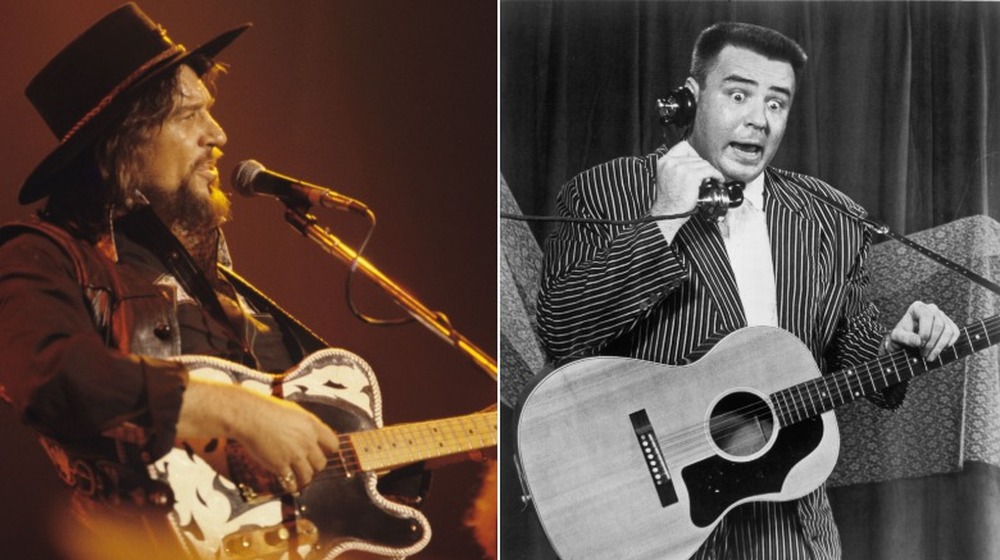

It was Buddy Holly, says Ultimate Classic Rock, who chartered the small plane, and it was a given that he was going to get one of the three seats. Originally, he had gotten it for him and his band members, guitarist Tommy Allsup and bass player Waylon Jennings (left). Fate had other ideas.

It started, says Texas Monthly, with the Big Bopper (right). He'd been feeling sick, and by the time the Clear Lake show happened, he was deep into a bout of the flu. He hadn't had the chance to sleep, and the plane wasn't just more comfortable, it was a chance to grab some shut-eye on the other side. He approached Jennings, asked to swap, and they did.

Years later, Jennings told the Tennessean that the incident had haunted him for the rest of his life — and not just because of the swap. As they said goodbye for what would be the last time, Holly had joked that he hoped Jennings' bus broke down. Jennings responded, "I hope your ol' plane crashes."

Jennings later said, "... I blamed myself. Compounding that was the guilty feeling that I was still alive. I hadn't contributed anything to the world ... compared to Buddy. Why would he die and not me?"

Heads' up

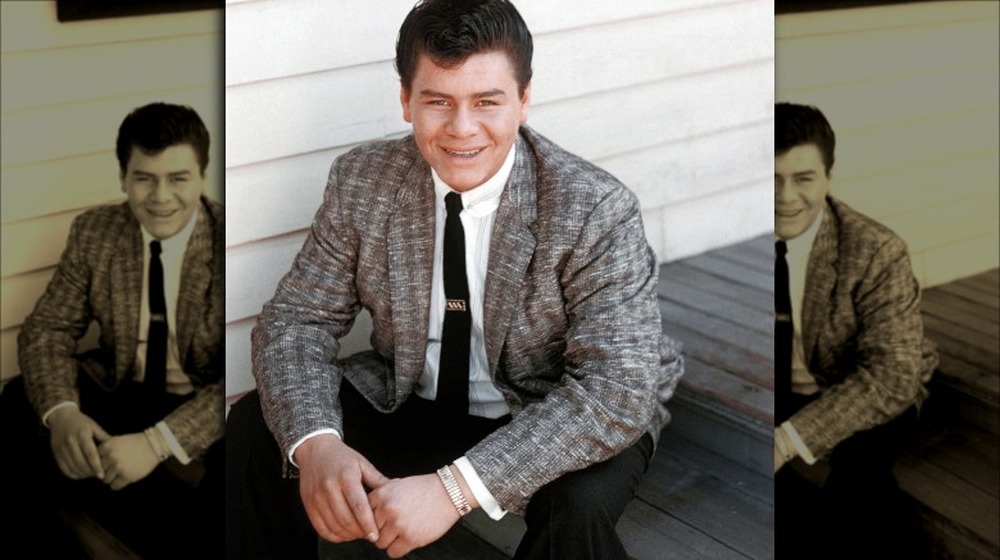

Hearing about the deal that J.P. "The Big Bopper" Richardson had made with Waylon Jennings, Texas Monthly says that Ritchie Valens (pictured) started working on Tommy Allsup for his seat. Allsup refused — repeatedly — until the very end.

It was when Allsup headed back into the club to make sure they'd packed all their gear that he ran into Valens as he signed a final autograph. He asked one more time, and Allsup pulled out a coin. They flipped, Valens called heads and won the seat. Still, the BBC says Allsup was originally listed as one of the crash victims — he'd given Buddy Holly his wallet and ID and asked him to pick up his mail when he got to Minnesota.

Allsup went on to a major career of his own, playing guitar for performers like Willie Nelson, Roy Orbison, Merle Haggard, and — appropriately — Jennings. He was also a talent scout, producer, and rep for Liberty Records (via Texas Hill Country). Allsup died in 2017 — at age 85 — and his son, Austin, said that he had always seen that coin toss as "a blessing," one that he paid tribute to in the name of his Dallas bar — Tommy's Heads Up Saloon.

Among those who reached out to Austin with condolences was Valens' sister. He told ABC that he had replied, "...now, my dad and Ritchie can finally finish the tour they started 58 years ago."

The official ruling

The plane Buddy Holly had chartered was only in the air for a few minutes, but it wasn't found for a while. According to Texas Monthly, Jerry Dwyer — the owner of the plane and Dwyer Flying Service — had spent hours trying to contact the plane and track it by calling airports along the presumed flight path, to no avail. Area airports were closed because of the blizzard, and it was only when Dwyer was able to get up in the air with one of his other planes that he spotted the wreckage. Since there had been no fire, This Day in Music says that it went unnoticed for hours — in spite of the crash site being just a quarter of a mile from the closest road.

The Civil Aeronautics Board launched an investigation, and the complete lack of evidence of equipment malfunction was initially baffling. Then, they turned to the pilot. Roger Peterson's record was less-than-stellar, with his flight instructors noting a few important details — he was licensed, but he didn't have the certifications he needed to fly only by instruments, and he had previously been written up as "susceptible to distractions," as well as disorientation and vertigo.

The cause was determined to be pilot error. Experts believed that he had read the instruments incorrectly and backwards and believed that they were gaining altitude when they were, in fact, losing it.

The show must go on

While it might seem like a given that the remaining dates of the tour would be canceled, that actually didn't happen. According to Rolling Stone, local acts were brought in to fill the slots of those killed in the plane crash, and some of those last-minute fill-in acts ended up becoming massive stars in their own right.

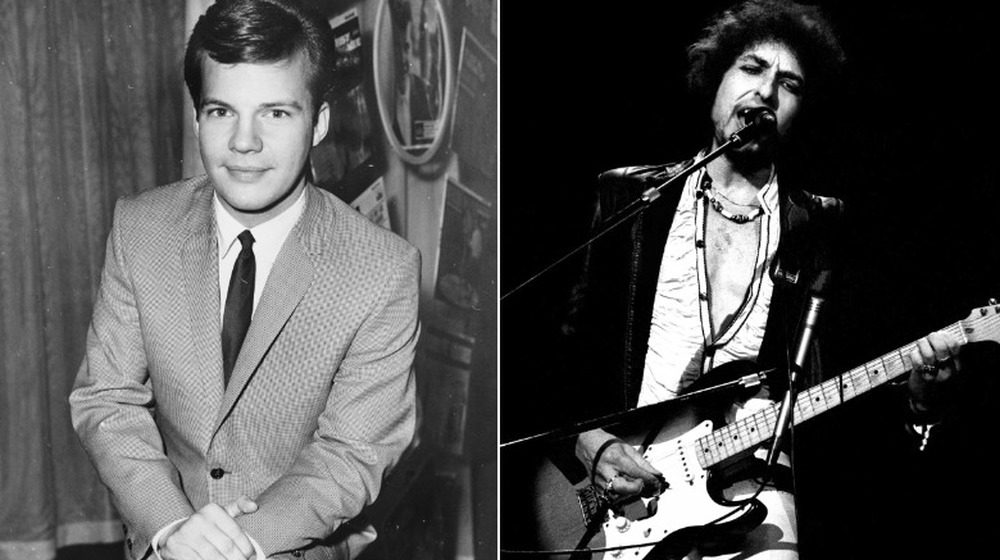

Robert Velline (left) of Fargo, N.D., was just 15 years old when he and his band — the Shadows — were called in to perform at the Moorhead, Minn., show. Velline — who went on to change his name to Bobby Vee — called the show "the start of a wonderful career," and it was. Within a matter of months, The Toronto Star reports he recorded his first hit — "Suzie Baby" — and signed with Liberty Records. Between 1959 and 1970 he had 38 songs in the Top 100, and there's another footnote to this part of the tale, too. One of Vee's fellow bandmates from the Shadows also went on to an illustrious career, and that was Bob Dylan.

Vee was still recording and touring decades later, and in 2011 he was diagnosed with Alzheimer's. He released one more album — The Adobe Sessions — on the 55th anniversary of that fateful plane crash and passed away in 2016. He was 73.

Just how much influence has Buddy Holly had?

Buddy Holly had a terribly short career. U Discover Music says that his first studio records were made on Jan. 26, 1956 — just three years and a handful of days later, he was gone. Still, his contributions to music were staggering, and it's impossible to imagine what he would have done had he lived to the ripe old age he should have.

Rolling Stone has him sitting comfortably at Number 13 on their list of 100 Greatest Artists list, and it's John Mellencamp who wrote his entry. He calls Holly "one of the first great singer-songwriters" and lauds him for his ability to make every person in the audience feel as though he's speaking to them.

Fender adds more — not only was Holly "the first cool geek," but he was also the first high-profile star to use the Fender Stratocaster. Even (possibly) more important, he pioneered something else — the now tried-and-true rock band format of two guitars, bass, and drums seen in countless other groups.

Without Holly, it's unlikely there would have been the Beatles, at least in the way everyone's familiar with today. U Discover Music notes that the Beatles covered Holly in their early Cavern Club days, and Texas Tech says that in 2014, Paul McCartney (who bought Holly's entire catalogue of songs) arranged to have his tour go through Lubbock, because he had always wanted to play in Holly's hometown.

The widowed bride

Don McLean's "American Pie" — the song that popularized the phrase "The Day the Music Died," mentions a widowed bride. That's Maria Elena, who was married to Buddy Holly for just six months before he died.

According to The Telegraph, Maria Elena quickly got a reputation as a fierce — and, according to some, unreasonable — guardian of his legacy. Their relationship had moved shockingly fast — she was a receptionist working for one of his publishers, and on their first date he excused himself, bought her a rose, and proposed. (She still has the rose.) She had originally been going to travel along with them on the Winter Dance Party Tour but declined at the last minute — she was pregnant.

Even as Holly's mother heard the news of his death on the radio, Maria Elena saw the report on the television. She miscarried the following day, and according to Time, that tragedy is why authorities will no longer release the names of victims until their families have been notified.

She later told Texas Monthly that after his death, she retreated from the public. Four years after the crash, she remarried, and it was her second husband who eventually convinced her to tell Holly's story — starting with giving the go-ahead for the 1978 movie, The Buddy Holly Story. Still, it hasn't been easy, and she says she's still called "the Spanish Yoko Ono" because of how difficult she's been to work with.

Calls to reopen the case

In 2015, something odd happened — there was a serious call to reopen the investigation into what had caused the plane crash that awful day in 1959. According to The Guardian, federal investigators were, in fact, considering reopening the case, and the rumors about what might have happened were strange.

Two months after the crash — and the ruling of pilot error — Plane & Pilot says that a .22 caliber pistol was found at the site. That — and the fact that J.P. "The Big Bopper" Richardson's body had actually been found in a neighboring field — led to rumors that the cause had actually been an accidental discharge of the gun, and theories suggested that Richardson had been shot.

Texas Monthly spoke with the plane's owner, Jerry Dwyer. In spite of the fact that no bullet holes in the plane or the bodies were ever identified, Dwyer remained convinced there was more to the story. He claimed that he was in the midst of writing a book about what really happened, and added that he had kept pieces of the wreckage because it backed up his theories.

Not long after the possibility of reopening the investigation was announced, the Associated Press reported that the National Transportation Safety Board had refused the request.

An exhumation and a grisly auction

J.P. Richardson's son — Jay Richardson — never met his father. His mother was pregnant when the crash happened, and according to Today, it was the younger Richardson who hired a University of Tennessee forensic anthropologist to examine and x-ray his father's remains in an attempt to put rumors to rest once and for all.

Knox News says the whole thing started in 2007, when Richardson's son was preparing to move him to another area of the cemetery where he was buried. When they opened the casket, they found a body that was in "remarkably good condition" and were able to x-ray the remains. The findings were grisly, but telltale — nearly every bone was broken — ruling out theories that he had survived and attempted to go for help. And there was no trace of a gunshot wound.

After Richardson's son took the opportunity to sit with him for a while, he later announced he was going to auction off his original casket. He would be reburied with a life-sized statue and marker, and according to SF Gate, he had been planning on using the money to fund a musical about his father's life.

Don McLean and "American Pie"

Don McLean's "American Pie" is one of those iconic songs that — when it comes right down to it — no one knows the meaning of. McLean has been notoriously tight-lipped when it comes to revealing what the song is actually about, and according to The Guardian, there's only a few things people seem to agree on — its a lament for the loss of the American dream amid the chaos of the 1960s, a downward spiral with a beginning marked by the deaths of Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and J.P. Richardson.

McLean has — sort of — confirmed that yes, "The Day the Music Died" was always meant to be about Holly, who was a childhood idol. But he adds that it was just as much about his own family, and if there's any consolation, he's said why he doesn't like talking about the lyrics and exactly what they mean. "... I don't like talking about the lyrics because I wanted to capture and say something that was almost unspeakable. It's indescribable."

The music, as they say, may have died that day, but it will never fade away.