The Untold Truth Of The Chicago Cubs

Cubs Win! Cubs Win! Holy Cow! Those lovable losers known as the Chicago Cubs are no longer the latter. After 10 innings of a memorable game 7 in the 2016 World Series, the Chicago Cubs finally erased 108 years of heartache and won a world championship. But how exactly did the Cubs achieve such an epic run of futility? Curses? Bad breaks? Goats? You think you know "your Cubbies?" Think again.

Why are they the Cubs?

Baseball teams haven't always had nicknames, or at least official nicknames. The 1800's were a bit fast and loose with baseball nomenclature. For example, the 2016 World Series runner-up Cleveland Indians were once known as the Cleveland Naps — they weren't lazy or anything, they were just named after player-manager Napoleon Lajoie. It wasn't until 1915 when the team took the name "Indians," after a former superstar Cleveland baseballer, Louis Sockalexis.

There are no bears wreaking havoc in Illinois today (especially in the NFL). There was a time that yes, bears and their offspring cubs were indeed around, but that's not how the name came about. Prior to "Cubs," the Chicago baseball team used "White Stockings," which morphed into "White Sox" and was adapted by Chicago's south side American League team. Next, the National League Chicago team went by "Colts," referring to the youth of the squad. Famed manager Cap Anson left the team after the 1897 season, leading to the destructively descriptive "Orphans," used from 1898-1901. The 1901 season was a disaster, leading to another youth movement in 1902. Rather than be repetitive, a new nickname emerged. No longer young horses, this team would be young bears. And thus began the Chicago Cubs.

The Friendly Confines weren't always for them

As long as you don't ask Bostonites, the answer to "what's the most famous ballpark" is Wrigley Field in Chicago. With its ivy-lined brick walls, cozy neighborhood feel, and raucous frat-party feel, the only thing missing from Wrigleyville is a beer pong table in left field. Not bad for a bunch of squatters.

1914 was a full six years after the Cubs won their (until this year) final World Series, and the landscape of baseball was as different then as it is today. A rival baseball league emerged, called the Federal League. The Chicago club, the Whales — and no, there weren't any whales in Illinois then, either — looked to stake a claim on the north side. Owner Charles Weeghman commissioned a stadium erected at 1060 West Addison, and the Whales played their first game on April 21, 1914 to approximately 21,000 fans. But the success of the Federal League was only apparent in Chicago — the rest of the league hemorrhaged money and folded after the 1915 season.

The Cubs pounced on the opportunity to head north. April 20, 1916 marked the first home game — a win — for the Cubs at Weeghman Field, which then became Cubs Field, and which finally became Wrigley Field in 1926. And yes, they're named after the gum people, in case you thought corporations renaming ballparks was a new thing.

Their old stadium is a medical college

Turn-of-the-century Chicago baseball resided on the south side with the White Sox, and the West Side with the Cubs. And despite the Cubs' baseball dominance — winning the World Series in 1907 and 1908, and falling just short in 1910 and 1906, the White Sox consistently outdrew their more dominant western Chicagoans.

The fall of the Federal League was just what the Cubs needed. The West Side Grounds, called home by the Cubs from 1893 until the Wrigley move in 1916, is now the University of Illinois Medical Center. The former home plate rests inside a nondescript college building. Prior to a 2009 plaque marking the former location, time consumed what was once a great ballpark. The move north saw a spike in attendance, and helped cultivate the Cubs culture we all know today.

The 1906 Cubs are the greatest team ever ... to lose the World Series

The 1906 Chicago Cubs were simply unbeatable, and no team has yet to top the .763 winning percentage of their 116-36 record (and no team won as many games until 2001). An amazing 50-8 run ended the season — they were "en fuego" before sportscasters could coin that as a catchy phrase on a $7-per-month per subscriber network. To make things even sweeter, they actually outdrew the White Sox! As the ultimate capper, the two met in the World Series for city, state, and world championships on the line.

The White Sox were dubbed the hitless wonders — they batted a paltry .230 as a team during the season. In a time when home runs were rare due to cavernous ballparks and a "dead" ball that didn't travel like the balls of today, the Sox hit only seven. Simply put, this was an epic mismatch, but the White Sox didn't get the memo. After splitting the first four games, the Sox took two straight in a momentous upset to capture the crown. Famed first baseman Frank Chance said "There is one thing I will never believe, and that is the Sox are better than the Cubs."

Tinkers to Evers to Chance: they hated each other

There's a few baseball limericks that stand out, but only one that speaks to the awesome power that was the 1906-1910 Cubs. The July 10, 1910 Saturday Evening Mail published Frank Pierce Adams's homage to the deadly double play combo, entitled Baseball's Sad Lexicon. What Adams, and most everyone else, didn't know is "Tinkers to Evers to Chance" only went together on the diamond and in prose.

First baseman Frank Chance was also the manager and, while it's not like he didn't like the other two, it's hard to be chummy-chummy with your boss. As for shortstop Joe Tinker and second baseman Johnny Evers, they shared the kind of hatred usually reserved for religious wars. Despite the smooth fielding the two shared on the field, off it they didn't speak for decades. Yes, plural. Evers traces the origin to 1907: "One day early in 1907, he threw me a hard ball; it wasn't any farther than (10 feet). It was a real hard ball ... I yelled to him, you so-and-so. He laughed. That's the last word we had for — well, I just don't know how long."

Frank Chance died in 1924, but not before the three got together again and reconciled. Although the names are rarely seen apart, Joe Tinker does has a solo memento — a former minor league park in his adopted hometown of Orlando is named for him.

They were the first to wear pinstripes and alternate uniforms

When you think of the New York Yankees, you think of the pinstriped uniforms that give the Yanks their air of class and style. But just like names changed in old-timey baseball, so did uniforms, and it was another team that showed people the classy style of pinstripes.

The 1907 Chicago Cubs introduced pinstripes to the baseball world, as an alternate uniform. And guess what? That too was a new idea! Today, multiple uniforms is a universal thing — in college, the Oregon Ducks have enough uniforms to not repeat any for 1000 years. But in 1907, it was inconceivable. The roar was along the lines of "back in my day we NEVER did something outrageous like three uniforms!" (or something like that).

Baseball's ruling party (this was before it had a commissioner) ordered the Cubs back to their traditional jerseys after a mere one game. The next year, the Cubs wore the pinstripes as their everyday road uniforms. The copycat league, being what it is, soon saw more teams following the trend, before New York and a certain Babe made it theirs forever.

Hey, speaking of ...

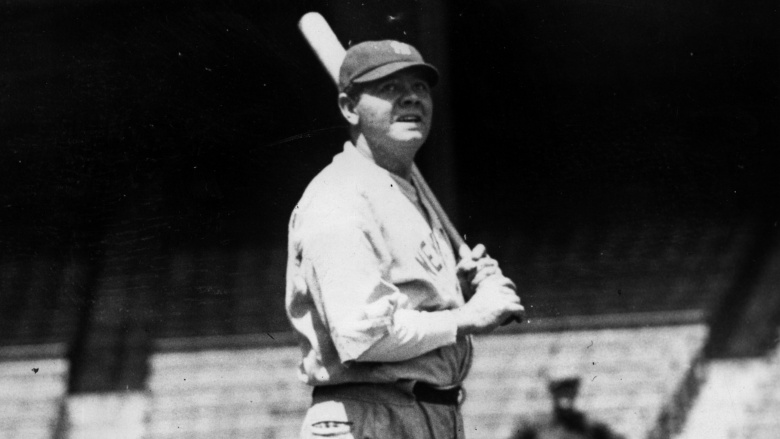

Babe Ruth's called shot

Even the most casual of baseball fans knows the story of Babe Ruth calling his shot, confidently pointing to center field and blasting a towering home run right where he said he would. The truth is, there's little doubt that Ruth pointed. But at what?

It was October 1, 1932 — Game 3 of the World Series between the Yankees and the Cubs. The Yankees, up 2-0, now traveled to Chicago, and the Cubs faithful were doing everything they could to throw off the powerful Yanks. When Ruth took batting practice, he was on the receiving end of a barrage of boos, and even lemons! Who brings fruit to batting practice? The catcalls didn't sway the Sultan of Swat, as he smacked a towering home run in his first at bat.

It's the fifth inning where the legend began. Cubs pitcher Charlie Root got ahead of Ruth with a strike, and the crowd roared. After two straight balls, Root got another by the Babe to make it 2-2. The crowd was going crazy, but then Ruth stepped out of the batter's box, gestured towards centerfield, and then CRACK! The crowd fell silent as Ruth hit a ... well, Ruthian home run shot right where he "pointed." That's exactly what the headline read in the New York World Telegram: "Ruth Calls Shot as he Puts Home Run No. 2 in the Side Pocket."

Ruth told the story numerous times, and you can actually see a video and hear the Babe describe the moment where he took Root deep and quieted the Wrigley crowd. But what did Ruth say before the legend became a "fact?" Early in the 1933 season, when asked, Ruth laughed and replied, "Hell no. Only a damn fool would have done a thing like that. There was a lot of pretty rough ribbing going on ... there was that second strike, and they let me have it again. So I held up that finger ... and I said I still have one left. Now, kid, you know damn well I wasn't pointing anywhere. If I had done that, Root would have stuck the ball in my ear." From the mouth of Babe.

Worst. Season. Ever.

Times got pretty lean for the Cubs. After a trip to the 1945 World Series, the Cubs ran into a bit of a dry run. And when we say dry, we mean Sahara. For 20 years, the Cubs only finished over .500 once, and finishing 82-80 in 1963 isn't exactly something to brag about. But compared to what happened the year before, it was as good as that magical 1906 season.

1962 was a first for Major League Baseball. To accommodate an increasing fan base, baseball expanded by two teams, adding the New York Mets and the Houston Colt .45's (later Astros). Being expansion teams, they weren't very good — they only had access to marginal players via an expansion draft, so they were mostly loaded with rookies and has-beens.

Yet somehow, the 1962 Cubs managed to only finish above one of them. The Mets were deplorable, winning only 40 games. But the Cubs, a storied franchise, scratched a mere 59 wins. That meant the lowly Colt 45's beat them in the standings. A sign of things to come happened in the first series in 1962, when the Colt 45's swept them, recording two shutouts and allowing a mere two runs over three games. A bunch of nobodies did that. Houston finished six games ahead of the Cubs and beat them 14 out of 21 times during the season. The Cubs have had many bad seasons, but finishing behind an expansion team is definitely the worst one ever.

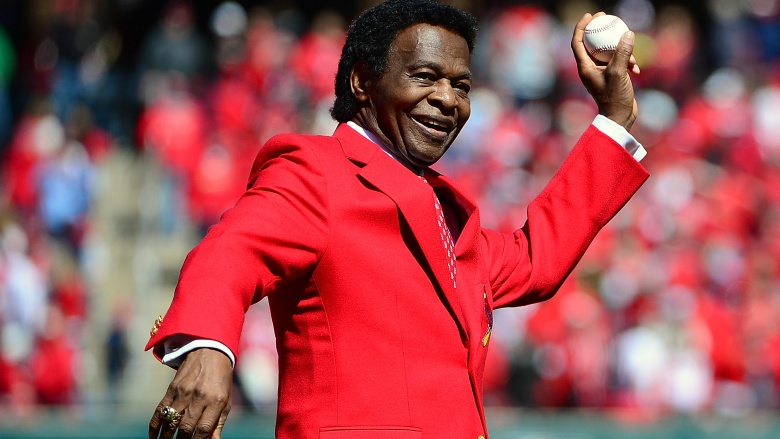

The Worst. Trade. Ever, really wasn't

When you're a lovable loser, you do lovable loser things. Like trading away a can't-miss superstar and future Hall of Famer for a nobody pitcher and a few magic beans. That's exactly what the sad-sack Cubs did, trading Lou Brock away for some guy named Ernie Broglio. Cubs! How could you! You adorable losers, of course you could!

The Brock trade is pointed out as a defining Cubs moment — just as Clemsoning is a term that applies to a sports team choking away a lead, "Cubbing" would be getting rid of that can't-miss prospect for a slab of tripe. That being said, a funny thing happened on the way to revisionist history class — the Cubs actually made a good deal. Yes, Brock was only 24, but he was a .251 lifetime hitter, and struck out a lot. Broglio had a 21-win season in 1960 and was just coming off an 18-win season. He was only 28, and basically getting into his prime. But the Cardinals pulled a fast-one on the Cubs — on paper it looked like a good trade, but Broglio had arm trouble going back to 1960. Brock caught fire for his new team en route to a Hall of Fame career, a reputation as one of the best base-stealers in history, and a whole farm full of eggs on the Cubs' collective faces. Today, it's possible Broglio wouldn't pass a physical and the trade would be voided, but back then, the Cubs just got hosed by their arch-nemesis Cardinals.

The truth behind the Cubs curse

No team in professional sports has (had) the "did I run over a Gypsy?" bad luck of the Chicago Cubs. It all started when a fan tried to bring a goat to the 1945 World Series. After being denied entry, William "Billy Goat" Sianis cursed the club to never win a Series again (spoiler alert: it didn't work). Who can forget 1969, when a black cat cursed the team and they Clemsoned away the division to the Mets?

And of course, there's the piece de resistance: poor, poor Steve Bartman, who supposedly cost the Cubs a shot at the 2003 World Series, when he took away a sure pop-out from left fielder Moises Alou. That alone ended the game, and the series, and the Cubs lost. At least, that's how it played out in the national media, a story that couldn't be further from the truth. First, had Alou actually caught the ball, it would have only been the second out. Instead, with a 3-0 lead, pitcher Mark Prior walked Luis Castillo. The Florida Marlins got it to 3-1 when Miguel Cabrera hit a routine ground ball to shortstop Alex Gonzalez. It was the kind they hit when taking infield practice to get you loosened up, and Gonzalez booted it. So, instead of being out of the inning with a two-run lead, the Cubs gave up 8 runs to trail 8-3.

But wait there's more! This was only Game Six. The Cubs still had a full game to win, make everyone forget about Bartman, and go to the World Series. But, they blew that one too. It took until 2016 to prove that it wasn't a goat, a black cat, or an unsuspecting fan just trying to get a souvenir that screwed the Cubs. The Cubs just made many bad plays for a long, long, long, long time. There's no curse, and there never was a curse. It's just that you win by getting good players, executing good plays, and winning games. The Cubs didn't do that for 108 years. But now they have.