The True Story Of The Hermetic Order Of The Golden Dawn

In London in 1887, there began the formation of a secret society, known as the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. Its purpose was the practice of magic, the study of the occult, and the secret engagement with the paranormal — all activities that had the potential to scandalize the predominantly Christian society of Victorian England. By the turn of the century, the organization would count among its members some of the most prominent artists and intellectuals of the day, all partaking in the esoteric practice of ritual magic.

However, the mystical group soon burned itself out. Amid inner strife and factionalism, the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn had all but disbanded by 1903. But the legacy of the secret society continues to be felt, and the relatively small group is known today for the immense effect it had on some of its most famous members and for its central importance in the workings of magical organizations right up to the present day. Here is their true story.

Occultism and Freemasonry in the 19th century

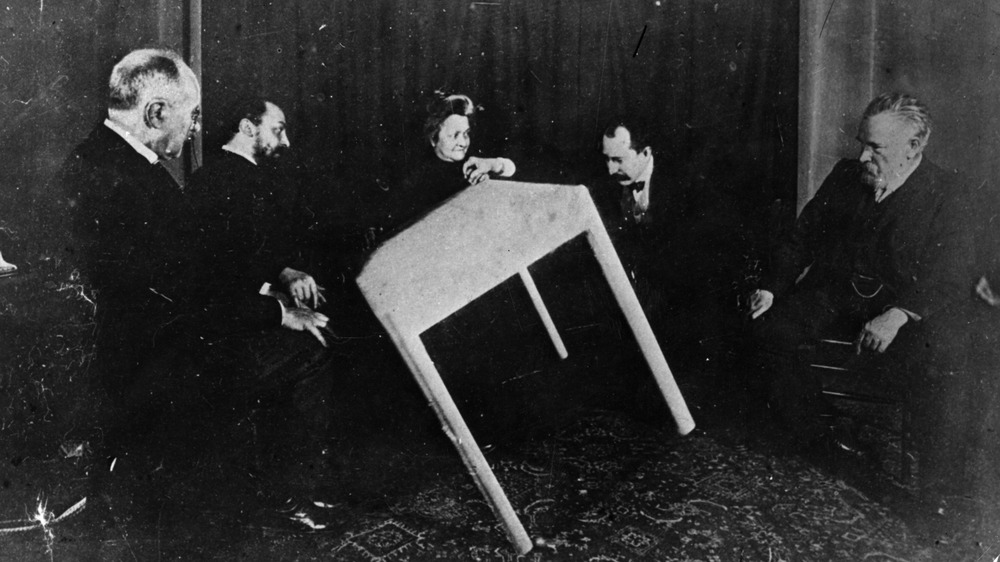

Though Victorian society was famously puritanical, it was also deeply curious about the mystical aspects of human existence and the forces at work in the world. According to the academic A. Butler, "All sorts of respectable men and women were dabbling in dubious pastimes such as ritual magic and attempting to communicate with the dead." Butler's book, Victorian Occultism and the Making of Modern Magic, lists communication with angels, interplanetary travel, mystical healing, and, on rare occasions, the ability to cause bodily harm to others as desired outcomes for magical practice. But more common than these eccentric hopes was something more fitting with the stereotypical view of Victorian society — the need for spiritual advancement.

"Men and women across Britain were joining magical societies in an attempt to evolve into their 'true selves,'" says Butler. "They believed that ancient wisdom passed down over centuries through cabalistic, Hermetic, alchemical, and occult sources held the key for individuals to gain access to their divine beings."

New advancements in metaphysics and the dawning of humanity's understanding of evolution invited a new appraisal of religious orthodoxy that, while not skeptical in the secular sense, invited more eccentric, less conventional investigation of spirituality. The Theosophical Society and practitioners of Freemasonry had both long sought to further the spiritual development of members by engaging with mystical symbols and rituals, prefiguring the activities of magical societies like the Golden Dawn.

The discovery of the cipher manuscripts

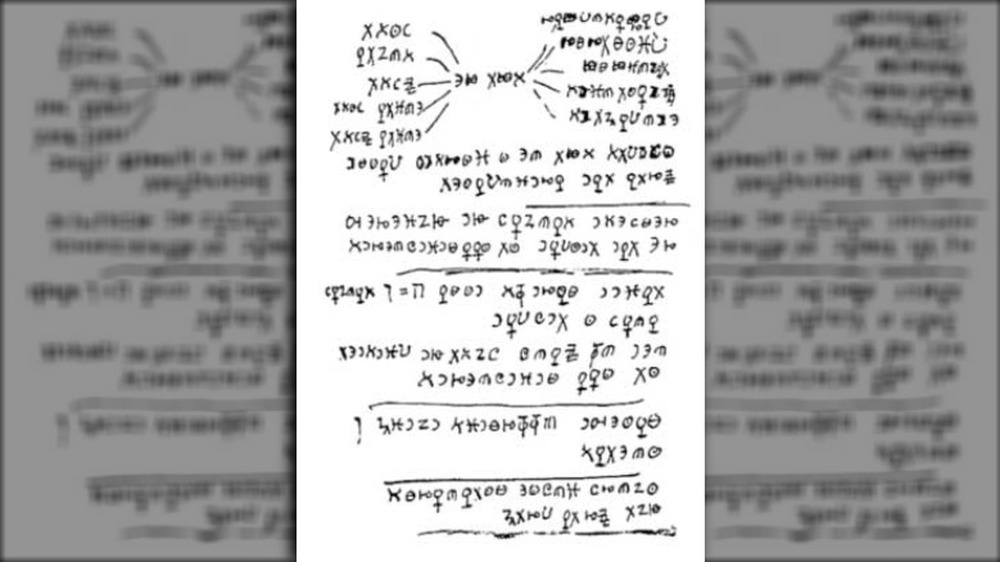

The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn owes its origins to a single text — the mysterious Cipher Manuscripts. This 56-folio bundle of encoded writings in black ink on cotton paper was watermarked 1809, according to the Thelemagick Library. The origins of the Ciphers have been debated ever since they came to light in the mid-1880s. In a time when esoteric texts were rare, and many books were still printed in small quantities and hand-bound, it was common for documents to be shared among like-minded members of the same groups and societies. As such, the actual author of the Ciphers is still unknown, but they came into the possession of one William Wynn Westcott, a Freemason and member of the Societas Rosicruciana in Anglia — an esoteric Christian group that practiced mystical rituals — based in Warwickshire, England, who otherwise worked as a coroner by day. Westcott, who would later become one of the founders of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, claimed to have received the Ciphers from the Rev. A. F. A. Woodford, according The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn® in Britain, a fellow mason who in turn received them from the Masonic scholar Kenneth R. H. Mackenzie.

Westcott set about decoding the Ciphers, which were written in English but coded from right to left using a simple cryptogram based on Johannes Trithemius' Polygraphia, according to the Hermetic Library.

The founding of the Golden Dawn

William Wynn Westcott (pictured) decoded the Cipher Manuscripts in 1887, and work revealed was the skeletal descriptions of a set of magical rituals and occult teachings assembled from a wide range of mystical sources, including Qabalah, the tarot, and aspects of alchemy. According to BRANCH, Westcott shared his findings with two other masons — William Robert Woodman, a police surgeon who, like Westcott, was a member of the Societas Rosicruciana in Anglia, and Samuel Liddell "MacGregor" Mathers, a member of many Masonic groups who lectured in esoteric systems of thought.

Working together, Westcott, Woodman, and Mathers began to construct from the decoded Ciphers the rudiments of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, working the rituals and mystical teachings uncovered by Westcott into a curriculum for spiritual improvement and the learning of ritual magic, as well as the study of magical philosophy. Fortune telling rituals such as tarot card divination and astrology were combined with magical rites that purported to allow for contact with supernatural beings and the dead, "synthesizing pre-existent magical traditions and producing a modern magical system," according to A. Butler.

On Feb. 12, 1888, Westcott, Woodman, and Mathers signed "pledges of fidelity" to their new order, the Golden Dawn, thus becoming the founding members.

The curious case of Fräulein Sprengel

Potential new members of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn were recruited by word of mouth, according to BRANCH, via pre-existing occult networks and connections already established through Masonic lodges, though the new secret society also advertised for members in the Theosophical journal Lucifer.

Though the origins of the Cipher Manuscripts were seemingly unverified — and indeed rumors abound that the work was the creation of one of the occultists from whom William Wynn Westcott had claimed to receive it, or else it was a forgery by Westcott himself — there was one detail that supposedly lent legitimacy to the Ciphers in the eyes of potential new occultist recruits. According to Heterodoxology, Westcott claimed to have found among the pages of the Ciphers the address of one Fräulein Anna Sprengel of Stuttgart, which spoke of the woman's magical credentials and her belonging to a well-established lineage of Rosicrucian mystics in Germany. The note referred to Sprengel as "Sapiens Dominabitur Astris," — or, "the wise among the stars" — and "a chief among the members of the goldene dammerung" — or "Golden Dawn." Westcott claimed that it was through contact with Sprengel that he, William Robert Woodman, and Samuel Mathers were bestowed the right to lead a British version of the order, with Sprengel herself purportedly chartering the first Golden Dawn Temple in England.

However, no evidence of the existence of Fräulein Sprengel has ever been found, and many critics have argued that the figure was a creation of Westcott himself.

The Golden Dawn's structure and teachings

Members of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn "were primarily interested in magical philosophy and traditional ritual practice for the advancement of the individual's spirit," according to BRANCH, who explain that the curriculum created by William Wynn Westcott and his fellow founders centered principally on leading members through the "scholarly study of symbols and rituals that would help them attain a higher level of spiritual being through natural magic."

The Outer Order comprised the first three levels of the curriculum. Focusing on the use of tarot and other forms of divination such as geomancy outlined in the Ciphers, inductees were taught to use these tools for spiritual development, while each level also involved the in-depth study of the symbolic meaning and "metaphysical character" of each classical element — earth, air, fire, and water, each level followed by a written examination similar to a school test.

According to BRANCH, the Inner Order was the creation of founder-member Samuel Mathers, who became established as the exclusive group's leader. Mathers (pictured) named the order the "Ruby Rose and the Cross of Gold," and among this group of adepts, members would experiment with ritual magic to accomplish feats such as astral projection and scrying — the summoning of visions. Inner Order members also tutored new recruits and could recommend new inductees.

The Golden Dawn's Secret Chiefs

The founders of the Golden Dawn referred not only to the authority of the mysterious — though, apparently, human — figure of Anna Sprengel. They also claimed that the order was guided in part by "Concealed Rulers of the Wisdom of the True Rosicrucian Magic of Light," according to Encyclopedia.com – beings known to the members of the order as the "Secret Chiefs."

According to BRANCH, the Secret Chiefs were kept a mystery to the outer orders, and contact with them could only be made by the highest-ranking adepts within the lodge. In 1891 founding-member William Robert Woodman passed away, and around the same time, William Wynn Westcott's apparent long-running exchange of letters with Sprengel came to an abrupt end, when he declared he had received word that his correspondent in Germany had also died. Samuel Mathers, who had been instrumental in setting up new Golden Dawn temples around the country and also in Paris, made the timely announcement that he had been in contact with the Secret Chiefs. Many at the time believed that the Secret Chiefs were alchemists whose lineage began in Ancient Egypt. Indeed, many of the Golden Dawn's rituals involved the invocation of Egyptian gods such as Horus, while the first Temple in London was named "Isis-Urania," the first part of which is the name of the Egyptian goddess of nature and magic.

But Mathers worked to suggest that the Secret Chiefs were themselves otherworldly, disembodied beings and positioned himself as the intermediary between the chiefs and the order.

Westcott's sudden departure

With William Robert Woodman already passed on, Samuel Mathers was left in supreme command as the only remaining founder-member when, in 1896, William Wynn Westcott decided to step away from the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, a seemingly surprising decision. Why did a man who was a long-time occultist and student of magic decide to abandon the order right at the point it was becoming popular?

A. Butler cites a letter Westcott sent to Frederick Leigh Gardner, an occultist and member of the Golden Dawn who had a long association with the Freemasons and Westcott's earlier esoteric society, the Societas Rosecruciana in Anglia, in which Westcott explains how his secret interest in the occult had seemingly become public, with ramifications for his job as a coroner (pictured).

"It had somehow become known to the State officers that I was a prominent official of a society in which I had been foolishly posturing as one possessed of magical powers — and that if this became more public it would not do for a Coroner of the Crown to be made shame of in such a mad way," he said.

Westcott went on to say he believed there was a conspiracy to out him — "I cannot think who it is who persecutes me — someone must talk."

The Golden Dawn's huge popularity

The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn hit its peak in the middle of the 1890s, according to BRANCH, when among its hundreds of members were counted a number of key figures in Victorian society, all interested in the occult for the purpose of spiritual betterment and the pseudo-scientific exploration of the nature of the world and humanity's role in it. Notable writers such as the poet W. B. Yeats and Welsh fantasy horror writer Arthur Machen joined in rituals and mystical study with leading West End actress Florence Farr and the Irish revolutionary Maud Gonne (pictured). A. E. Waite, the co-creator of the classic Tarot deck known today, and Aleister Crowley, the writer and eventual creator of a knew religion known as Thelema, were also prominent occultist members.

The difference between the Golden Dawn and other esoteric groups of the time was the secret society's admission of women as members. Only men could be Freemasons, for example, a rule which still stands to this day. The Golden Dawn's comparatively progressive leanings — with rules derived in part from the Cipher Manuscripts – lent their gatherings the feel of a social event, while many of the rituals created an atmosphere of playful titillation, according to numerous academics.

BRANCH states that around this time Samuel Mathers claimed to have received instruction from the Secret Chiefs for the syllabus of a third level of learning, involving alchemy and "spiritual sexuality."

W. B. Yeats and automatic writing

For many members of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, mysticism and the occult were not simply eccentric hobbies. Rather, they were considered avenues through which to achieve greater understanding of themselves and the world — both material and spiritual. As such, the teachings of the Golden Dawn affected other aspects of their members' lives.

William Butler Yeats — who would go on to win the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1923 — was a member of the Golden Dawn and its later incarnations for 30 years. The roots of his interest in the occult have been widely studied. "The path to conventional Christianity had been cut off for Yeats by his father's religious scepticism, but his need to believe in something and a hunger for the spiritual life led him to seek and devise an alternative system of beliefs," claimed the Irish Independent.

Yeats' long interest in mysticism reached its apex following his marriage to fellow Golden Dawn member Georgie Hyde-Lees in 1917, when, on their honeymoon, his wife announced that she could channel voices from supernatural "instructors." Without the need for another intermediary, the couple began what would be a series of more than 400 "automatic writing" sessions, the results of which would impact heavily on Yeats' later poetry, particularly in his work, A Vision, published in 1925.

The malign influence of Aleister Crowley

Aleister Crowley is, alongside William Butler Yeats, one of the most famous — or, in his case, notorious — members of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. His controversial membership and behavior within the group would have grave ramifications for the survival of the order and the position of its leader, Samuel Mathers.

Crowley, who would one day be described in the British press as the "wickedest man in the world," joined the Golden Dawn in 1898 and would later boast of his "rapid" progress through the outer levels of its occult curriculum, according to his biographer, Lawrence Sutin. Crowley's interest in the occult was, to say the least, unconventional — a way of subverting the fundamentalist Christianity that had dominated his childhood (as a child, Crowley's mother had called him "The Beast"). Crowley struck up a close friendship with Mathers, who attempted to initiate the young occultist into the Inner Order later that same year but was refused by the other London members who were suspicious of Crowley.

According to BRANCH, Mathers decided to force the issue in 1900, by inducting Crowley into the Inner Order at the Ahathoor Temple in France. It was a decision that would signal the end of Mathers' leadership of the Golden Dawn, as the order descended into bitter revolt.

Years later, Crowley would critically undermine the order by publishing their secrets in his magazine, Equinox.

Infighting and dissolution

According to Francis King's Modern Ritual Magic: The Rise of Western Occultism, Samuel Mathers' close relationship with Aleister Crowley had long been a cause for concern among the order's members, especially those in London and Edinburgh, who were also frustrated by Mathers' position as intermediary between them and the supposed "Secret Chiefs" with whom he claimed to be in contact.

Crowley enraged the London temple upon his return by stridently announcing his induction into the Inner Order and demanding the esoteric documents to which he was now supposedly entitled. Florence Farr, who had already stated she thought the temple should be closed down, resigned, and as infighting grew, Mathers came to suspect the involvement of William Wynn Westcott, who he believed was attempting to reclaim control of the order. Mathers reacted by writing a letter claiming that Westcott's correspondence with Anna Sprengel was a forgery, and that he had never had any contact with any Secret Chiefs (via BRANCH).

But by attempting to smear another founder-member, Mathers saw his own credibility also dissipate. He was removed from his position within three months of his induction of Crowley to the Inner Order by the remaining London adepts, and the order splintered into clusters of smaller groups, with A. E. Waite taking over the Isis-Urania Temple, Yeats joining a group called the Stella Matutina that practiced the earlier rituals of the Golden Dawn, and Mathers forming a new group, Alpha and Omega.

The Golden Dawn's enduring legacy

Francis King claims that at the point when the Golden Dawn Adepts were rebelling against Samuel Mathers' leadership, the founder performed a ritual in which he gave the names of the rebels to a handful of dried peas, and, shaking them in a sieve, cursed them to burn themselves out with continual quarrels and disagreements so that they may never unite again. King states that Mathers' curse could be considered successful. Never again did any of the occultists who practiced ritual magic as members of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn organize into such a diverse and impressive group, and never would they again achieve the same level of influence, Mathers included.

But that isn't to say that the Golden Dawn hasn't had a profound influence on esoteric thought and magic practices throughout the 20th century and beyond. Aleister Crowley used the occult practices he learned within the order to found Thelema, the basis for modern new religious movements such as Wicca (pictured) and various strands of paganism, while the Cipher Manuscripts continue to attract those interested in the practice of magic.

A version of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn has since reformed and still exists today.