The Tragic Deaths Of The Crew Of The USS Indianapolis

Stephen Spielberg's classic film, Jaws, is perfect in building tension. The shark, which you don't meet until one hour and 21 minutes into the movie, is a malevolent and mysterious force — its absence makes it more terrifying. The tension reaches a height when Robert Shaw's character, Quint, spellbinds audiences with a dark monologue of his travails in shark-infested waters after the sinking of the USS Indianapolis in 1945. His description of how his friend was bitten in half by a shark bite chills the heart.

Shaw's speech was based on a true story that was far more ghastly and grim than summer box office fare. The USS Indianapolis was arguably the worst, and definitely the most, terrifying disaster in American naval history. The 879 crew members who perished represent the greatest loss of life in a United States Navy vessel. What makes the disaster even more grievous is the manner of their deaths and the ultimate tragedy of the ship's skipper, Charles B. McVay, III.

USS Indianapolis' Secret Mission

The USS Indianapolis was a battle-scarred veteran of World War II's Pacific front. Called affectionately, Indy, the heavy cruiser had seen action from New Guinea to the Aleutian Islands. It led the charge in taking the Gilbert Islands and then the Marshalls. The ship's last major action was to bombard Okinawa in March 1945. The ship took damage and withdrew to the Naval Yard at Mare's Island near San Francisco.

It was there that the Capt. Charles B. McVay, III, received secret orders to carry a small load of cargo to the island of Tinian. The chief medical officer reported McVay saying, "I can't tell you what the mission is. I don't know myself but I've been told that every day we take off the trip is a day off the war." The Indy made the 5,000-nautical-mile crossing to Tinian in ten days, arriving on July 26, 1945.

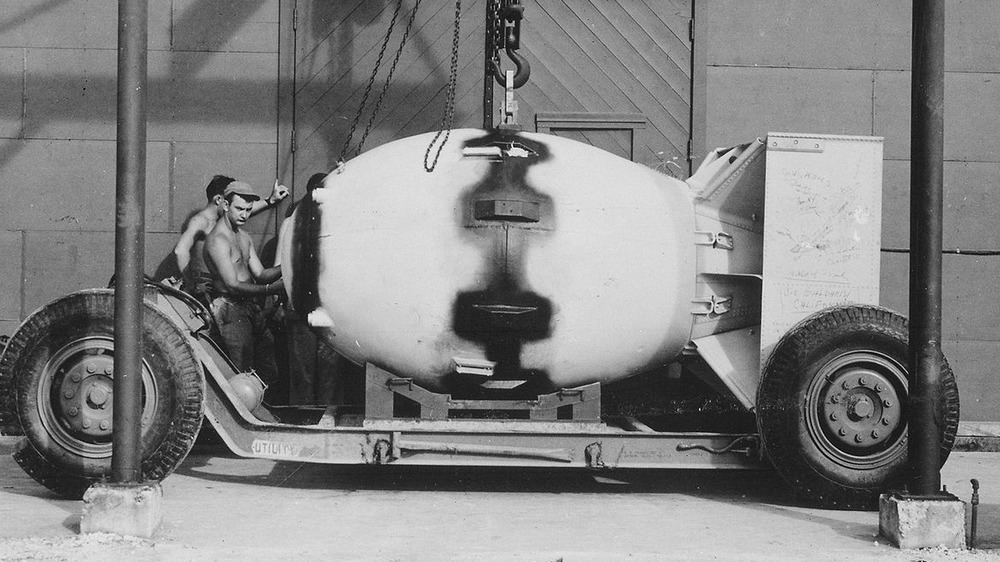

McVay and the crew of the Indy learned later that they had delivered components of the first atomic bombs — "Little Boy," which leveled Hiroshima, and "Fat Man," which destroyed Nagasaki. According to author Dennis Wainstock, the parts took up one large box and a small cylinder containing uranium-235.

After Tinian, the Indy made for Leyte vis-à-vis Guam. They were about halfway there when a Japanese submarine, I-58, commanded by Mochitsura Hashimoto, sighted the USS Indianapolis. It was a little after midnight on July 30, 1945, when two torpedoes peeled across the Philippine Sea.

900 survive... for now

The torpedoes slammed into the USS Indianapolis' bow and amidships. This made short work of the veteran cruiser. It only took 12 minutes to sink, bow first, before slipping to its tomb, which, according to National Geographic, was 18,044 feet below. The sudden change of fortune was striking. Some 300 of the 1,195 crew were killed immediately. These may have been the lucky ones.

Those that lived clawed for Kapok life vests and cut out as many of the ship's life rafts as possible. Some scrambled down the ships' side, others jumped into the sea, which was glossed with a thick veneer of fuel oil. According to a recount by Capt. Lewis L. Haynes, chief medical officer onboard the ship, the crew leaped into the muck of oil sloshing with sea water before swimming away hard to escape being sucked down with the ship. It was chaotic and confusing. There were hardly enough life rafts. The vast majority of men bobbed like corks covered with viscous oil. They formed a long, dirty string that stretch over the open ocean for a mile or more. They prayed for rescue.

The USS Indianapolis goes unreported

For the USS Indianapolis, no rescue was forthcoming. According to an official account by the Navy, distress messages had been sent by Capt. Charles B. McVay's crew, but these were not received. In fact, on July 31, 1945, the naval staff at Leyte removed the USS Indianapolis from its arrival board. This was a standard practice during World War II. Combat ships were assumed to have arrived on time unless other information became available. What failed in this instance is that the naval officers who knew the ship was overdue did not investigate why.

Another failure occurred when naval intelligence received information that the Japanese had sunk something in the area where the Indianapolis was expected to voyage. This was reasonably explained by the Navy since through the course of the war there had been hyperbolized claims or fake intelligence promulgated by Japanese forces. There was a sufficient amount of this misinformation that through the war, naval intelligence looked skeptically at Japanese reports. The intelligence was shared with top brass, but they chose to disregard it.

Different ways to die for USS Indianapolis crew

If the survivors of the USS Indianapolis knew that naval headquarters were not aware of their disappearance, they may have lost hope then and there. Still, the 900 men clung to the thought of imminent rescue. But it became apparent that they were swimming in a nightmare of epic proportions.

The first trouble was exposure. At first, the fuel oil from the wreck acted as a crude sunscreen, but the survivors soon drifted into clear waters that provided no shelter from the sun. Men's skin burned by day and then although the tropical water was warm, it was still colder than human body temperature. At night especially, life was slowly sucked away as crew succumbed to hypothermia. This grew worse as hours stretched to days.

Those particularly at risk were those who had sustained injuries when the ship initially sank. The chief medical officer, Lewis L. Haynes, recalled, "There was nothing I could do but give advice, bury the dead, save the life jackets, and try to keep the men from drinking the salt water when we drifted out of the fuel oil."

With hardly any freshwater to speak of, the men were sorely tempted to drink the seawater. Those who did, fell victim to salt poisoning. First they suffered diarrhea, followed by more dehydration, and then became maniacal. Men hallucinated seeing the ship beneath them full of food and water. They thrashed about desperately and drank even more seawater, thinking it would cure their thirst.

"A Blood-Curdling Scream"

It is estimated that up to 150 of the USS Indianapolis' crew were killed by sharks (via Smithsonian Magazine). At first, the sharks largely concentrated on the dead. However, by at least the second day, the living were targeted. Those who were injured with open wounds drew the sharks first because of the scent of blood.

To ward off the sharks, the crew took to pushing out the dead bodies, hoping that by sacrificing them to the sharks they'd be left alone. One ensign, Harlan Twible, organized shark watches when they noticed that the animals tended to attack those survivors who floated alone. So they gathered in large groups. When a shark approached, the men beat at it to drive it away. Those in the center of a group fared best.

Survivor Edgar Harrell recalled, "You see maybe a body up on an eight foot swell and all of a sudden that swell breaks and that body comes down and he hits you and he leaves parts and residue on you. You see that and you wonder, 'Is that going to me tomorrow or yet today?'"

Another survivor, Clarence Hershberger, who was interviewed by the Palm Beach Post, only saw one or two sharks but recalled, "But you knew they were there because somebody would let out a blood-curdling scream like you never heard before. And you knew someone had been hit, usually on the outer edge of the group."

What kind of shark was it?

So what species of shark attacked the crew of the USS Indianapolis? The great white shark, the shark from Jaws, is according to National Geographic, statistically the most dangerous shark, along with bull and tiger sharks. However, in the case of the Indy, the main culprits were oceanic whitetips.

The oceanic whitetip is heavily built and reaches up to 13 feet in length. They earned their name from the flecks of white that are prominent on the sharks fins. While these sharks primarily range in the open ocean far from humans, they are considered potentially dangerous to humans, according to the Florida Museum, often seen in waters around boating disasters. However, whitetips typically feed on fish such as marlin and tuna but have also been observed to eat sea turtles, squid, seabirds, and garbage.

It is an aggressive species that shows little fear. Once plentiful through the world's oceans, the oceanic whitetip has become a victim of bycatch and rising demand for shark fins. It is estimated by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), that the species has declined between 80% and 95% in the Pacific since the 1990s. In 2018, NOAA listed the species as threatened under the Endangered Species Act.

Madness and suicide

The crew of the USS Indianapolis would not have cared about what species of shark was attacking. To them, it was a continuous nightmare as some of the crew slipped into madness when signs of rescue failed to materialize. By their second night in the water, men's minds broke from lack of hydration and food, witnessing the continuous death of their shipmates, and the terror of the sharks.

Doug Stanton, in his book, In Harm's Way: The Sinking of the U.S.S. Indianapolis and the Extraordinary Story of Its Survivors, tells of how men's thoughts turned to suicide. Once-sane crew pulled off life vests and immersed themselves in the water, never to surface again. Others flopped into the water, face first. When a shipmate pulled them out, they did it again. Then some crew broke ranks from their huddles and gave themselves to the sharks, hoping for a quick end to their torment.

The suicides, the drowning, the hypothermia, the exposure, the saltwater poisoning, and the shark attacks continued on for two more endless nights.

Rescue of the USS Indianapolis crew

By the morning of Aug. 3, 1945, there were a little over 300 crew of the USS Indianapolis left. The only solace was in prayer. But that morning, things changed as a Navy PV-1 Ventura piloted by Wilbur "Chuck" Gwinn flew over the disaster area on a routine patrol. He was cruising at 3,000 feet and had a 20-mile view of the blue Pacific about him. He was far too high and at too odd an angle to see the macabre drama unfolding below him.

However, according to authors Lynn Vincent and Sara Vladic, the plane's antenna had broken. Gwinn turned over the controls to investigate, which brought him to the bottom of the plane. There was a window on the deck through which he saw, to his utter amazement, an oil slick. After tracing it, he found the survivors and radioed for help. By that evening, rescue craft had arrived in full force and evacuated the victims. Search operations continued until August 8, 1945.

The Navy's scapegoat

Of the 1,194 crew, only 316 survived. In the immediate aftermath, a court of inquiry recommended Capt. Charles B. McVay, III, be court-martialed. Adm. Chester Nimitz disagreed and issued a letter of reprimand to McVay instead. However, according to Capt. William J. Toti from the U.S. Naval Institute, the chief of naval operations, Adm. Ernest J. King, overruled him and ordered a court-martial. There has been speculation that King railroaded McVay in order to shift blame from the failures of the upper echelons of the Navy. Also, it has been asserted that King, who was known as being a tempestuous and vindictive man, had a personal grudge against McVay's father from his days at the U.S. Naval Academy.

McVay was in a court martial from Dec. 3 to 19, 1945, the only time during World War II that a skipper was tried for losing his vessel. According to the records, he was charged with failing to issue orders to properly abandon the ship and for failing to take proper zigzagging evasive maneuvers to avoid submarines.

At the trial, Mochitsura Hashimoto even appeared to give testimony, stating that zigzagging would not have saved the USS Indianapolis. This was presumably lost in translation. McVay was acquitted of the first charge and found guilty of the second. He lost a chunk of his seniority, which was later restored by Navy Secretary James Forrestal. McVay retired in 1949 as a rear admiral. However, the blame of the disaster was firmly fixed on McVay.

Aftermath of the sinking of the USS Indianapolis

As you can imagine, the psychological toll on the crew was devastating. It would be fair to say, however, that Capt. Charles B. McVay, III, bore the brunt of it. To the families of some of the victims, McVay was being let off too lightly for the deaths 879 husbands, fathers, and sons. At first, he received weekly letters from them leaving no room for argument as to their opinion, such as "If it weren't for you, my girls would have a father!" or "If it weren't for you, my son would be 25 years old today!" While the frequency of letters would subside over the years, they were always regular either during holidays, birthdays, or the anniversary of the sinking.

The surviving crew of the Indianapolis supported him, and McVay attended their first reunion in 1960. But the shadow, and evidently guilt, of the disaster never left McVay. On Nov. 6, 1968, at half past noon, McVay shot himself in the head with his service revolver outside his home in Litchfield, Conn.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

A middle schooler brings redemption

After the death of Capt. Charls B. McVay, III, the survivors of the USS Indianapolis wanted justice and exoneration for their skipper. It seemed clear to them that McVay had been made a scapegoat.

Yet the effort to exonerate McVay really began when Hunter Scott, a middle school student, interviewed survivors of the disaster in the 1990s for a class project. This caught the attention of congressmen. In 1999, the veterans of the Indy pressed for and received a hearing with the U.S. Senate Armed Services Committee, where they shared Scott's considerable research. They pressed for full exoneration. This cause was further supported by a letter from the then 90-year old Mochitsura Hashimoto to Sen. John Warner. "Our peoples have forgiven each other for that terrible war. Perhaps it is time your peoples forgave Captain McVay for the humiliation of his unjust conviction," Hashimoto wrote.

Warner introduced a resolution in 2000 to exonerate McVay. This passed, as well as a stronger version in the House of Representatives. The final version noted, "Captain McVay's conviction was a miscarriage of justice that led to his unjust humiliation and damage to his naval career; and the American people should now recognize Captain McVay's lack of culpability for the tragic loss of the U.S.S. INDIANAPOLIS and the lives of the men who died as a result of her sinking."

On the ebb tide

Over the years, the survivors of the USS Indianapolis have had regular reunions. At first, it was once every five years, but as more and more crew passed, they decided to make it an annual affair held in the city for which their ship was named. These reunions include a memorial service for those who were lost at the sinking and to honor those Indy veterans who have passed. This group, aside from their advocacy for Capt. Charles B. McVay, III, also were instrumental in the commissioning of a memorial to their lost shipmates, which also is in Indianapolis. It was dedicated in 1995. In its design, which includes a replica of the vessel, a piece of the USS Arizona was placed, connecting the first and one of the last ships sunk in World War II.

As of 2020, there are ten men left, according to the Reporter-Times, and the living memory of one of America's greatest naval tragedies will not last much longer. Still, it is safe to say that the sacrifices of the crew of the USS Indianapolis will be forever etched into naval history.