This Is What It Was Like To Feast In Ancient Rome

When it comes time to talk about the world's greatest empires, the Roman Empire is right at the top of the list. Everyone knows about it, but there's a ton of details that many might not know.

Take, for example, the fact that in 500 BC, Rome was just another city-state in Italy (via Vox). There was nothing super special about it, but by 200 BC, that little city-state had already taken over all of Italy, then had shrugged and said, "Might as well keep going, right?" It went from Republic to Empire, emperors kept conquering, and pretty soon there was Roman culture spilling all over the known world.

While Roman legions tried to keep the peace in the outskirts of the territory, Rome became known as the seat of opulence and luxury. It was the place where people gave up on stretchy pants and went right to togas, and those expanding waistlines might have had something to do with their love of feasting. The stories are legendary, but what is the truth behind the tales?

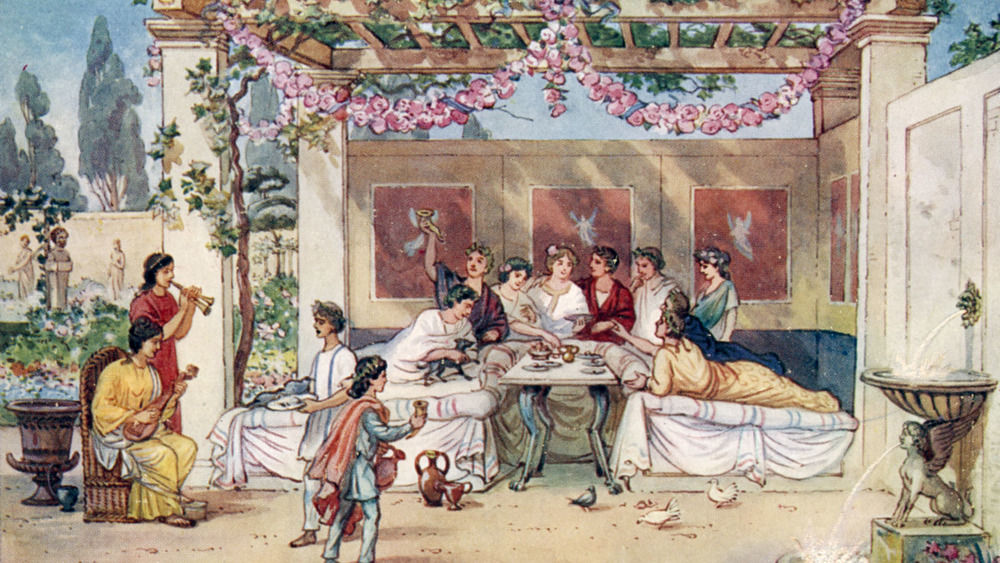

There were different kinds of banquets in Ancient Rome

When an important Roman shouted out to his friends, family, and staff that he was going to have a banquet, they needed a little more information. Why? According to The Met Museum, there were several different kinds. There were feasts like the epulum, which History and Archaeology says was a public, religious feast for the gods. Food would be placed in temples as offerings, and it was usually done around holidays or for occasions like temple dedications (pictured).

Then, there were more private affairs, like the cena. That was a frequently-held social meal that was pretty much a dinner party (via JSTOR), and after that, the fun really started at the comissatio. That translated into a late-night drinking party that could run to all hours, where it was more about the wine than the food — although there could be a little bit of that, too, says A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities.

It's also worth noting that in general, the banquet — which was called the convivium when talking in non-specific terms — was a pretty big deal in Roman culture.

Not everyone was feasting and banqueting

It's worth noting that feasts were mostly reserved for the upper class. According to Cornell University professor Barry Strauss (via NPR), "The banquet was a chance to follow the precept of keeping your friends close and your enemies even closer. They allowed emperors to display political power and wealth, and ... monitor political rivals."

While that means that an invitation to a banquet might be delivered via double-edged sword, other Roman citizens had more to worry about — like starvation. It might seem to fly in the face of the opulent image of ancient Rome, but according to Ancient World Magazine, Rome — especially early on — suffered from numerous crop failures and famines. Between 500 BC and 296 BC, there were at least 16 food shortages severe enough that consuls needed to tap into their network of contacts to find food and have shipped in.

Most ordinary Romans subsisted on a diet of vegetables, fruit, porridge, cheese, dates, and honey — for most, fish and meat were an expensive luxury they couldn't afford. Still, there were times when even those staple foods were scarce. Strauss says history has documented 19 food riots, with more that were likely forgotten. One — in the year 51 — was so bad that Emperor Claudius decided to high-tail it out of Rome while the gettin' was good.

All good things come in threes

Holding a Roman banquet the right way started with the basics, and that's the set-up of the triclinium. That's a word that literally means a "three-couch room," and unsurprisingly, that's what The Met Museum says was in a Roman dining room. The rooms were big enough to typically hold the couches — arranged against three of the walls — with a dining table in the center. The richer a person was, the fancier the couches: wood was common, but ivory wasn't unheard of.

Each couch had room for three people to sit, and they'd be served three courses. The gustatio came first, and that was basically the hors d'oeuvres. Then, there was the main course — called the mensae primae — and finally, dessert (or mensae secundae). Wine was served from start to finish, but it wasn't the same thing as modern wine, as attendees would mix their wine with water that was heated in purpose-built boilers called authepsae. (Other times, cold water or even snow was used.)

Tables were elaborate, and usually held multiple serving trays, drinking vessels, and a variety of utensils. The room itself was usually decorated with all the host's most impressive works of art and furniture, and of course there was entertainment, too. Music was just the start — guests could expect things like trained animals (like leopards) to entertainers who could mimic gladiatorial combat and perform pantomime plays.

Ancient Romans had to really like fish sauce

Condiments are important — just try eating a hot dog without one. The Ancient Romans had their condiments, too, and National Geographic says that they didn't just put it on their meat dishes, they put it on everything... even in their wine. It was called garum, and something comparable in the 21st century would be fish sauce. (And yes, right in the wine.) It was made by fermenting fish guts with salt, and it was such a big deal that massive production centers lined coastal areas, and yes, they were definitely smelled before they were seen.

The food at a typical Roman feast would not only be served with garum, but would also be used in the cooking process. Like today's olive oils or balsamic vinegars, there were different grades that were judged on things like consistency. Pliny the Elder said one of the best was made from mackerel and came from southern Spain.

Alone, garum was a thick liquid the color of amber. While it was sometimes used alone, NPR says it was also very often used as the basis of other sauces and dips. In other words? A typical Roman banquet table was covered with it.

Forbidden foods would have been on offer

Later in the Roman era, something interesting happened: sumptuary laws. According to Leiden University, these laws were essentially put in place to tell people what they could — and, more importantly, couldn't — serve at banquets. That seems like a weird thing to restrict, but remember that banquets weren't just about the food, they were about throwing a bigger and better banquet than your neighbor. Everything was getting carried away, and sumptuary laws were put in place to try to stop the madness.

The laws outlawed serving things like animals that had been artificially fattened: dormice (pictured), for instance, were a common sort of animal eaten by all classes, but it was only the elite who would artificially fatten them up — which became a no-no. The laws also restricted things like the type and quantity of exotic birds that could be served.

Keeping in mind the fact that people are basically all the same no matter what century they were born in, it's probably easy to guess exactly what kind of foods were on the dinner tables of the most impressive banquets: yes, the forbidden ones. The Met Museum says that when it came time to plan a menu for a banquet, a big part was deciding just which of the sumptuary laws would be flaunted this time.

Risking some good, old-fashioned lead poisoning

There's a lot of stories and theories about just how and why Rome fell, including the idea that the lead pipes Ancient Romans used in their plumbing contributed to mass lead poisoning and in turn, the wacky behavior their later emperors were known for. According to Time, it's a little up in the air as to whether or not it's legit to say lead poisoning caused the fall of Rome, but it's completely reasonable to say that anyone who headed to a banquet was likely to get a not-so-healthy helping of lead poisoning.

Research has found that Roman water — that is, the water that ran through their aqueducts — had about 100 times more lead in it than the water that came from nearby natural springs.

And given that lead can accumulate in the body's tissues, that could be a huge deal. Medical Daily says that a buildup of lead can cause things like behavioral problems and a weakening of vital systems. Too much lead at once can result in anything from muscle weakness to death, and here's the thing — it wasn't just in the water. The face powders someone might use in getting ready for a banquet probably contained lead, and so did the cups, plates, and tableware people were using, and the pitchers and platters they were being served from. Drink up!

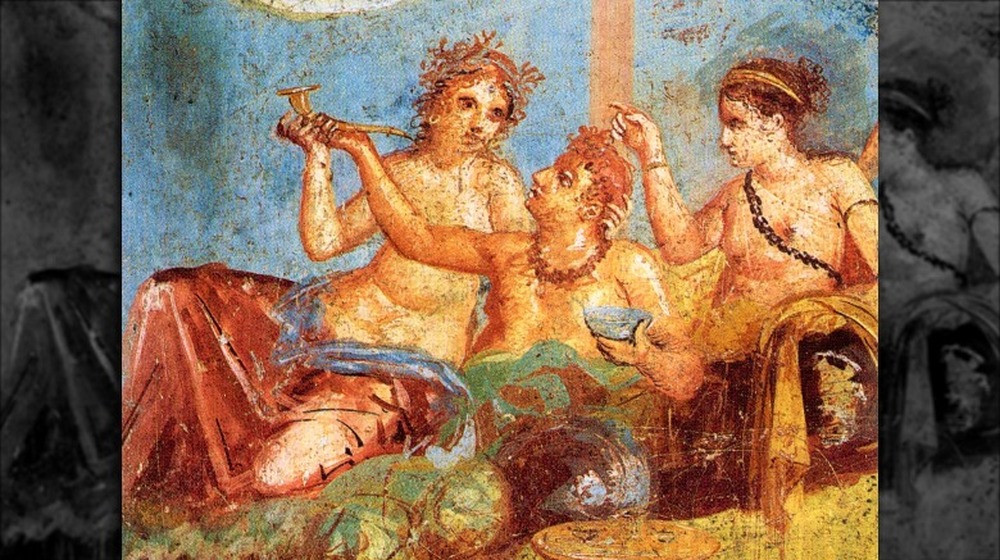

Sweetener — and the wine — was potentially deadly

Fun fact: most poisons taste bitter to us, because the flavor acts as kind of an alert that says, "Stop eating this, it's going to kill you." But that's not always the case. According to the Smithsonian, one poison — lead acetate — actually tastes so sweet that it's also called sugar of lead. The "lead" part should be a giveaway, but that brings us to ancient Rome.

Wine was typically served along with the entirety of the meal, and especially during the designated drinking part afterwards. The nobility — the ones partaking in the festivities — tended to have a huge tolerance, and could drink as much as two liters at a time. Unfortunately for them, the wine was usually sweetened with a compound called sapa. Sapa was — you guessed it — lead acetate.

While it's not clear just how much damage that much lead and that much wine could do, here's some food for thought. In 1047, Pope Clement died. His remains weren't submitted to modern forensic testing until 1959, and the diagnosis of lead poisoning was clear. What's that have to do with Rome? That particular pope preferred his wine sweetened and served the ancient Roman way.

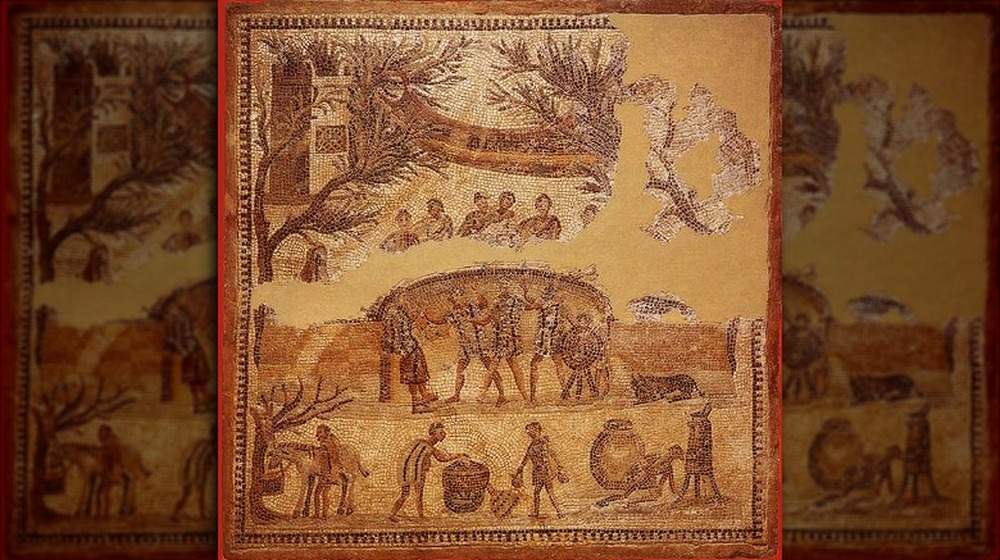

Foie gras is for amateurs

Foie gras — a dish made from the livers of ducks and geese that have been force-fed corn through a tube pushed into their throats — is highly controversial, hailed as extraordinarily cruel, and the BBC says that it's been banned in some countries and in some parts of the US. When it comes to Roman feasting, though, diners would have to leave their decency at the door.

According to research done by Leiden University, one of the things that sumptuary laws were put in place to stop was the serving of animals that had been artificially fattened, which were considered a little too extravagant to be responsibly served. Which is to say they were absolutely served.

Mainly, a Roman dinner table would have had a few types of these fattened animals. Fish — particularly red mullet and eel — were kept in fishponds and if they happened to survive captivity to adulthood, they would fetch a premium price at the market. Birds (like the thrush pictured) were kept in small birdhouses and fed things like mullet, fruit, seeds, and figs, while small animals like dormice were also kept in small pens and fed mainly with nuts. If only a few dormice were needed, it's thought they were kept in dark jars where all they could do was eat. Most often, these animals were served roasted, boiled, and stuffed with more food.

There may have been a food taster

Popular belief holds that Roman banquets and feasts were the perfect place to slip some poison in a rival's wine cup to get rid of them once and for all, but how true is that? Not particularly, says Cornell University professor Barry Strauss (via NPR). Actual cases of poisoning were pretty rare, but that's not to say there wasn't a certain amount of suspicion that swirled when someone suddenly became ill — or died — after a feast.

It wasn't uncommon, then, for some of the most powerful — and suspicious — Romans to have food-tasters present at their banquets. What's most surprising about this is that while it might seem like one of the worst jobs in history, it surprisingly wasn't — especially considering the fact that actual poisonings didn't happen too often.

Roman food-tasters were called praegustatores, and while they were often slaves, some came from the class of freedmen. And most importantly, it could be a steppingstone to a much more lucrative career. According to The New York Times, there were cases like the story of Halotus. He was a taster for Claudius, and he ended up getting a job as a provincial official... even though Claudius died on his watch. No risk, no reward?

The feasts of Elagabalus were just too much

There were feasts, there were feasts, and then there were the feasts of the emperor Elagabalus. He became emperor in 218, and the guy knew how to party. According to National Geographic, the stories about his short-lived reign are so wild that no one is quite sure where the truth ends and exaggeration begins, but they do know he was put on the throne thanks to the political maneuverings of his grandmother (who had him killed and replaced him with his cousin when he was 18-years-old).

There were a whole slew of scandals, but some involved his banquets. When he held one, he didn't just treat his guests. He was apparently fond of handing out "chances" to the everyman, and they were exactly that. Sometimes, a person had the chance of getting a steak. Other times, it might be a dead dog. Hilarious.

The Historia Augusta says that he had silver couches made for his banqueting rooms, all the serving vessels were also silver, and the banquets themselves would often be themed entirely by color. It was also rumored that he had a "reversible ceiling" built into that banqueting room, and once dumped so many rose petals on the diners that some were suffocated. Survivors of his shindigs could take their "chances," too, and walk away with banquet favors ranging from horses and carriages to lettuce.

A single surviving cookbook

Sure, there was a lot of food at a typical Roman banquet, and there wasn't just quantity, there was variety. According to NPR, a single Roman-era cookbook has survived. It's the work of Marcus Gavius Apicius and it's called De Re Coquinaria, or The Art of Cooking. It contains more than 400 recipes, and honestly? Not all of them sound appetizing.

Among the more cringe-worthy are recipes for brain sausages (which are brains, eggs, and herbs), liver kromeskies (pork liver wrapped in the membrane of the bowel), cucumbers another way (stewed with brains), rose pie (rose petals with brains), and stuffed pumpkin fritters (also with brains). Brains were used a lot.

Some dishes, however, sound pretty delicious — and modern. There were things like early fruit compote, scores of different sauces for different types of poultry (which included seasonings like cumin, celery seed, parsley, mint, and fennel), and plenty of ways to prepare beef or poultry stew. Even vegetarians might want to stay for dessert: on that menu were things like dates candied with honey, an ancient version of French toast, custards, and fruit served with cream. Getting through the brain course might be tough, but dessert sounds pretty good!

Ancient Roman banquets were carefully crafted for a particular reason

Cornell University professor Barry Strauss says (via NPR) that for some, banquets were an art form. Apicius ran himself into bankruptcy chasing delicacy after delicacy, but he's also credited with kick-starting a culinary pairing that's popular today: sweet and savory wrapped into one dish, like honey-glazed ham.

For others, guests lauded the simplicity of their banquets. The Caesars — Julius and Augustus — were widely praised for holding banquets that weren't only relatively simple, but comfortably informal.

And for others, well, it was the perfect time to have a little fun. Although historians caution that it's sometimes difficult to tell what's true and what's exaggerated, they also note that Emperor Domitian was known as being incredibly cruel, so this one isn't out of character at all. The story goes that for one banquet, he draped his hall entirely in black, had only black food served, and sat each guest alongside their own gravestone. The conversation was equally dark, and after putting the fear of death into everyone, he laughed, gave them some presents, and sent them on their way. He was a weird guy.

No, there wasn't a lot of vomiting

No conversation about Roman feasting would be complete without clearing up a little (albeit, gross) misunderstanding: no, the vomitorium wasn't a room specifically for purging the first round so newly-hungry diners could go back for more. Caillan Davenport and Shushma Malik are history professors from (respectively) Macquarie University and The University of Queensland. They say (via The Conversation) that in spite of the fact there's a weirdly large number of Latin words that are used around the process of vomiting, the vomitorium isn't one of them.

It's actually from a misunderstanding, and the earliest reference to a vomitorium comes from a 5th century text that's talking about passages in massive venues where spectators funnel into a space, then seem to be sort of vomited out as they rush for their seats. It's a structural setup and phenomenon that still happens today: next time there's a football game on television, think of teams spewing out onto the field and it'll all make perfect sense.

The mistaken belief that it has something to do with banquets comes from newspapers in the late 19th century. Comparison between then-modern parties and ancient banquets seems to be the first time the connection was made, and it crept into popular belief and pop culture. But don't worry — it's not the least bit true, and there's no reason to tarnish the gluttonous, extravagant imagery of the Roman banquet with some icky upchucking.