Why The Haitian Revolution Inspired So Many Rebellions

The Haitian Revolution not only led to Haiti's independence, but it set off a ripple effect of uprisings by enslaved people across the Caribbean and South America. Although not all of the revolts that it inspired were successful, each and every uprising chipped away at the sovereignty of colonial empires.

The Haitian Revolution was in turn inspired by the French Revolution of 1789, which set the standard for the ideals of liberty and freedom that nations had the right to aspire towards. Since the colonies were built on a "foundation of bondage, inequality, and prejudice," the hypocrisy of the French was promptly challenged. While earlier rebellions merely sought to withdraw from colonial society, the Haitian Revolution sought to completely overthrow the system.

France punished Haiti for aspiring to independence, and other rebellions were soon suppressed out of fear of repetition. But the Haitian Revolution remains a milestone in the history of independence movements and is the "only successful large-scale slave insurrection in history." Many also consider it to have initiated the decline of the slave trade. Unfortunately, despite attaining independence and abolishing enslavement in the Haitian Revolution, the legacy of enslavement "continued to have a profound impact on Haitian history." But although not all the uprisings that it inspired were successful, the success of the Haitian Revolution revealed the possibility of dismantling colonial empires. Here's why the Haitian Revolution inspired so many rebellions.

So what was the Haitian Revolution?

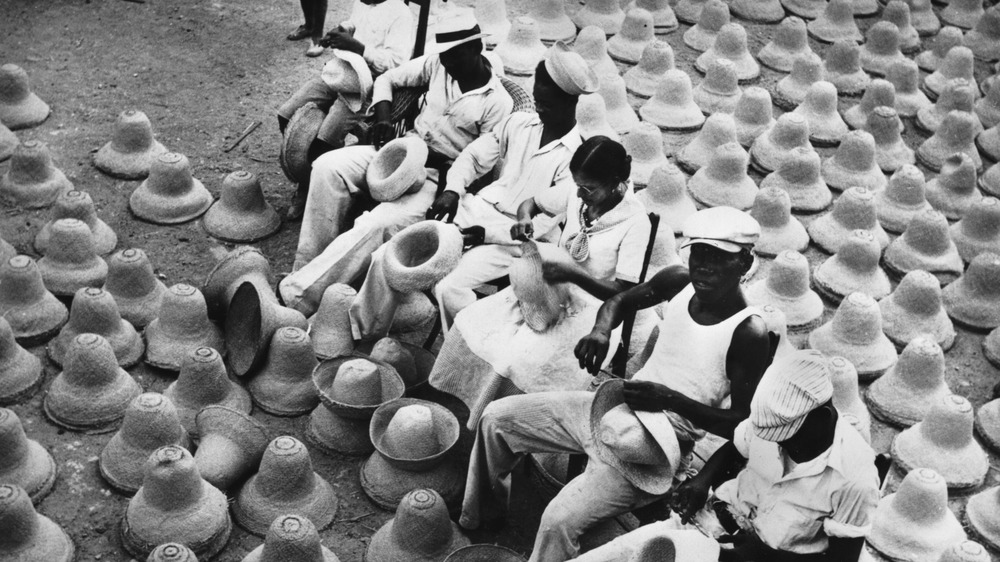

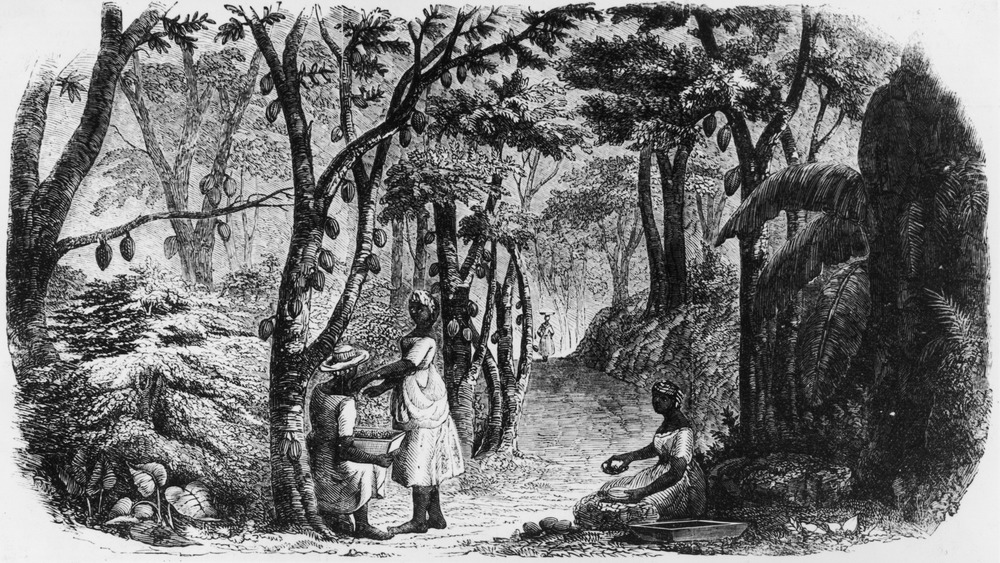

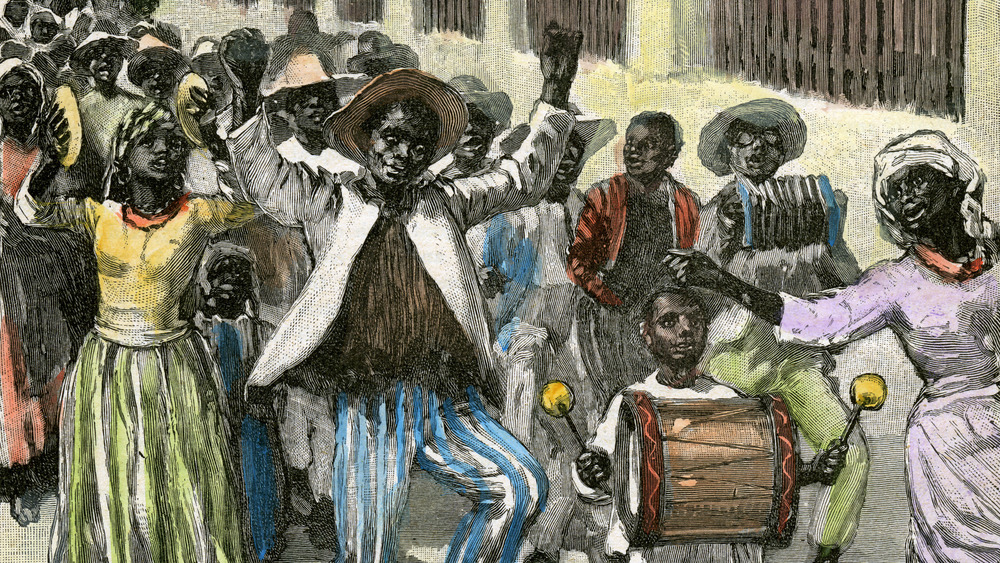

During the 1700s, Haiti was known as Saint Domingue and was using enslaved people as labor to produce cotton, coffee, sugar, and indigo. Haiti was also France's most profitable colony. Lasting from 1791 to 1804, the Haitian Revolution succeeded in abolishing slavery along with French colonial rule.

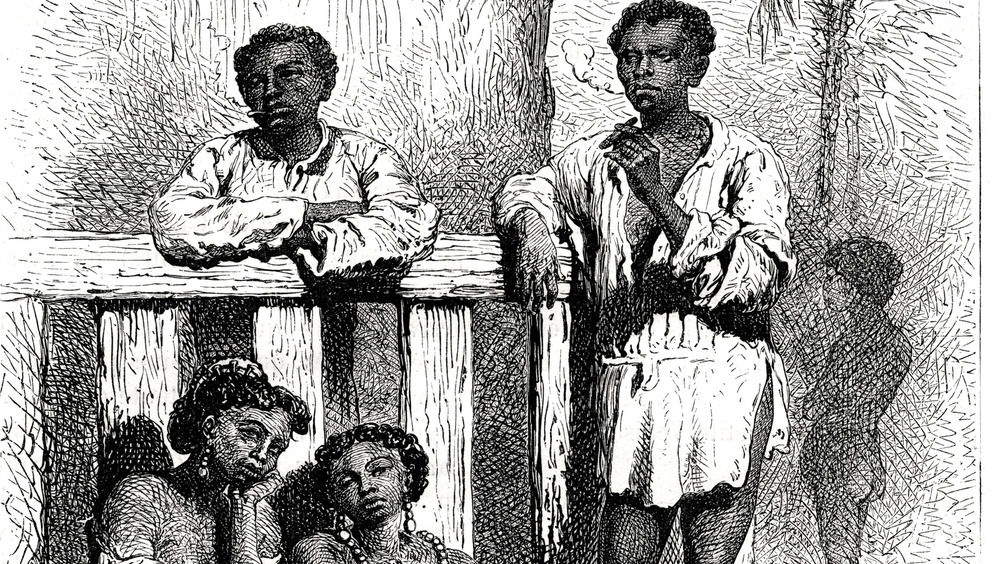

At the time of the French Revolution, there were upwards of 500,000 enslaved people in Haiti. In comparison, free Black people numbered 30,000, and free white people numbered 40,000. While there were several rebellions against enslavement before 1791, none were as successful as the one joined by Toussaint L'Ouverture on Aug. 21, 1791.

Born into slavery in 1743, L'Ouverture secured his freedom from his enslaver by the age of 30 and continued to work as his coachman for 18 years. But after a group of enslaved people revolted and set fire to plantation houses on the "Night of Fire," L'Ouverture was convinced to join the revolt and become a formidable military leader. By 1801, L'Ouverture's forces had conquered the colony along with the neighboring Spanish colony of Santo Domingo, now known as the Dominican Republic, and had succeeded in abolishing enslavement in the island of Hispaniola. L'Ouverture was captured and tragically died in prison in 1803, but his followers persevered under the leadership of Jean-Jacques Dessalines.

According to The Collected Works of Langston Hughes, on Jan. 1, 1804, Dessalines declared the colony's independence and renamed it Haiti, a name derived from the Indigenous Taíno-Arawak language, meaning "land of mountains."

Driving the British out of St. Lucia

Enslaved Africans in Saint Lucia were also inspired by the French Revolution, and in 1791, a group joined up with Maroons, or people who escaped enslavement, to protest and demand the freedom of all enslaved people. The march was reported to the British officials, and the leaders were captured and beheaded to discourage further dissent. According to Face2Face Africa, the heads were displayed around the town on spikes as a continual warning.

But in 1793, Flore Bois Gaillard, after escaping the plantation where she was enslaved, took refuge with a group of Maroons. Soon, she was the military leader of L'armée Française dans le bois, or the French Army of the Woods, and made a plan for a rebellion against the British colonizers.

The army successfully attacked British enslavers and plantations during the Battle of Rabot, and several people whom they freed from enslavement joined their army. Known as the First Brigands War, the British were eventually defeated on June 19, 1795. Unfortunately, no one knows what happened to Gaillard after the war.

In 1796, British invaded the island once again, starting the Second Brigands War, which lasted until November 1797. Although the British were against re-enslaving people, in 1802 the island was given to the French with the Treaty of Amiens, and enslavement was reinstated by Napoleon. Although the British reclaimed the island in 1803, true emancipation wouldn't occur until the British Slavery Abolition Act of 1838.

A martyr for freedom in Curaçao

Curaçao was conquered by the Dutch in 1662 after gaining independence from Spain, and within a century, the island was mostly populated by enslaved Africans. By 1795, inspired by 1791 revolt in Haiti, a slave named Tula led an uprising to declare Curaçao's independence.

According to Curaçao History, Tula worked on the Knip plantation, which was owned by Casper Lodewijk van Uijtrecht. On Aug. 17, 1795, Tula and 50 other enslaved people on the plantation went to Uijtrecht and informed him that they were no longer going to be slaves. They went to several more plantations to encourage people to take such a stance. By the evening, thousands of people had proclaimed their freedom.

Unfortunately, the uprising lasted little longer than a month, and after a month of bloodshed and battles, the Dutch captured Tula on Sept. 19, 1795. Tula was tortured to death publicly on Oct. 3, 1795, as a warning to other slaves. Uprising leaders Bastian Karpata, Louis Mercier, and Pedro Wakao, who'd also been captured, were summarily executed as well.

Slaves were told that they would be murdered if they refused to go back to their plantations. In an attempt to prevent future uprisings, rules were supposedly installed to prevent harsh treatment of enslaved people. While slavery was abolished in Curaçao in 1863, as of 2020 the island remains a Dutch colony. But the uprising of August 17 continues to be celebrated every year.

Overhearing talks of equality

José Leonardo Chirinos was born free to a free Indigenous mother and a Black enslaved father in Venezuela. After marrying a woman enslaved by Don José Tellería, Chirinos accompanied Tellería to Curaçao and Haiti, where he found out more about the events transpiring outside of Venezuela.

At the time, Haiti was still a French colony, but Chirinos was intrigued by Black Haitians' discussions of liberty and equality and was further inspired by Haiti's Revolution. Since Chirinos' wife was enslaved, their children were automatically enslaved, which inspired his "dislike for the institution of slavery." According to "Slave Revolts in Venezuela," by Angelina Pollak-Eltz, although rebellions by enslaved people happened occasionally, often the colonial authorities hastily "suppressed conspiracies" and executed the responsible leaders.

According to Executed Today, on May 10, 1795, Chirinos led a group of enslaved Congolese in the town of Coro to revolt and declare a new republic that abolished slavery and white supremacy. Unfortunately, colonial authorities promptly put down the rebellion, and many who were involved in the uprising were quickly executed. But Chirinos, who was captured in August 1795, wasn't executed until 1796. Chirinos' head was displayed on the road to Coro in a cage, and as retribution, his family was sold into enslavement.

Although Venezuela declared independence in 1811, since the "eurocentric aristocracy" had gotten involved in the liberation movement, enslavement wasn't abolished until 1850.

Defeat and deportation in St. Vincent

Saint Vincent and the Grenadine Islands were also inspired by the rippling wave of rebellions and revolts, and the island's conflict manifested as the Second Carib War, which was fought between Caribs, Indigenous inhabitants of the island, and British colonizers.

According to The African Diaspora Archaeology Network, St. Vincent's history is unique in that the first contact that Indigenous Caribs had was with African refugees. Many came to St. Vincent on slave ships that were "wrecked on the reefs or as escapees by boat and raft from the slave islands of St. Lucia and Barbados." Native Caribs were St. Vincent's final resistance against British colonization, but after the British initiated a takeover in 1796, the island was colonized by 1797.

Caribs were forced into an unconditional surrender, and many were deported to the island of Roatan. Over 5,000 Caribs were rounded up, and by March 1797, over 2,000 Caribs were deported. Those who didn't die, weren't exiled, and were able to evade capture fled to most remote parts of the island.

Slavery wasn't abolished until 1832, but due to the people's resistance, the institution of slavery lasted little over a generation on St. Vincent. The multi-island nation wouldn't attain independence until 1979.

A broken peace treaty in Jamaica

In Jamaica, the Maroons of Trelawny Town fought against British colonizers over the course of eight months in what is known as the Second Maroon War. According to Slave Resistance: A Caribbean Study, after the First Maroon War, white enslavers feared that free Maroons represented a "symbol of hope for the slaves who were still in captivity." This fear was compounded by the fact that Maroon villages "were a place of refuge for the runaway slaves."

The Second Maroon War began in July 1795, when the brokered peace treaty was broken by the public flogging of two Maroons. Not only were Maroons who were charged with crimes supposed to be "turned over to their own people for trial and punishment," but public flogging was a punishment typically reserved for enslaved people and so "was a deliberate and intentional insult."

According to Testing the Chains, by Michael Craton, at least 300 Maroon warriors and 200 people who'd run away from enslavement fought for eight months, but the final few surrendered by March 1796. According to Future Learn, over 500 Maroons, the majority of whom were women and children, were "deemed too dangerous and unpredictable" by the British and were exiled to Halifax, Nova Scotia. By 1800, those Maroons were once more displaced to the British colony in Sierra Leone.

Although the British Empire abolished slavery in 1833, enslaved people in British colonies continued to be indentured "until 1838 under what was called the 'Apprenticeship System.'"

7,000 lives in Grenada

On March 2, 1795, Grenada became the location of a fierce rebellion when over 100 free Black people under the leadership of Julien Fédon faced off against British colonizers. Before it was over, between 14,000 and 28,000 enslaved people had joined Fédon's uprising.

As the son of a free Black woman and a French father, Fédon was born free. But although he was resentful towards the treatment of Black people by the British, he himself owned at least 80 slaves.

Fédon's uprising couldn't have been possible without Gammy, an enslaved Afro-Grenadian woman who was vital towards helping Fédon organize and coordinate the villages with his attacks. Fédon's Revolution only lasted approximately 15 months, but it was one of the "first emancipation projects of the 18th century." Unfortunately, by June 1796, Fédon's group was defeated, and over 7,000 enslaved people had lost their lives to the fighting.

According to Face2Face Africa, Fédon aspired to make Grenada a "Black Republic just like Haiti," but the defeat of his uprising meant that the institution of enslavement remained in place in Grenada until 1834. Fifty people who were captured by the British were found guilty of high treason, and at least 30 others were executed for their role in the uprising. The British ultimately blamed the French Revolution for giving people fanciful ideas of liberty. Fédon, however, evaded capture, although many suspect that he died on a canoe out at sea.

The rejection of registration in Barbados

The Bussa Rebellion in Barbados was the largest uprising by enslaved people in the island's history. Led by Bussa, a West African man who was trafficked to Barbados in the late 1700s, the rebellion resulted in a two-day battle between the plantocracy, the West India Regiment, and at least 400 enslaved people led by Bussa, Franklin Washington, and Nanny Grigg.

According to Black Past, Bussa and other enslaved people began planning the rebellion after an Imperial Registry Bill in 1815 raised the potential for registration for enslaved people in the colonies. The uprising was planned from February to April, and over the course of a few months, enslaved people met at different coastal plantations to coordinate the rebellion.

On April 14, 1816, the rebellion broke out with the burning of cane fields. In the beginning, "over seventy estates were affected, forcing white owners and overseers to flee to Bridgetown, the colonial capital, in panic."

While only two white people were killed during the rebellion, after it was suppressed, over 140 people were executed over the course of five months. An additional 70 people were also sentenced to death, and 170 people were deported by the British to neighboring colonies in the Caribbean.

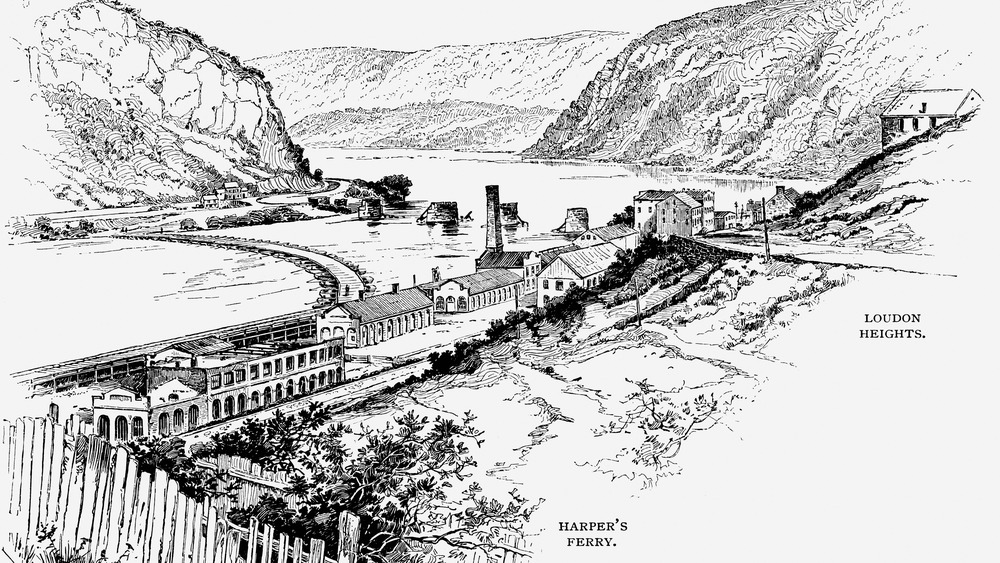

A failed raid in the United States

After reading a biography of Toussaint L'Ouverture, John Brown declared that he "ranked among history's greatest men." He avidly pursued literature about L'Ouverture for many years after as he dreamt of a "second Haitian Revolution" in America. In the end, his failed raid on Harper's Ferry was inspired by L'Ouverture's exploits.

According to The Indypendent, Brown spent time studying the Haitian Revolution in preparation for his raid, and when he was executed on Dec. 2, 1859, flags in Haiti were flown at half-mast. Brown was especially affected by the violence of the Haitian Revolution, and after being unable to reconcile his pacifism with revolt, he confided in Frederick Douglass "that he planned to employ the bloody lessons of the Haitian Revolution — guerrilla warfare and slave insurrection — in his crusade against American slavery."

The Haitian Revolution also had an unexpected effect on the United States territory when Napoleon sold the Louisiana Territory after losing Haiti. Brown was especially conscious of this, since the land attained in the Louisiana Purchase "served as a battleground for slavery."

Although the raid failed, fears of a second Haitian Revolution were stroked. White southerners were convinced that the "horrors of St. Domingo" would repeat themselves if the southern slave states stayed in the Union — a reference to the 1804 massacre, where between 2,000 and 5,000 white French people in Haiti were massacred after it was discovered that a few were planning to overthrow the newly independent government.

Lasting legacy of the Haitian Revolution

The Haitian Revolution was one of the strongest challenges to the colonial European order, but being fiercely rebellious was also fiercely punished. According to The Guardian, after Haiti's independence, former French enslavers demanded compensation. And in 1825, after agreeing to recognize Haiti's independence, the French King Charles X acquiesced to the former enslavers and ordered Haiti to pay a debt of $150 million gold francs in exchange for independence. The French set warships with loaded cannons in the Port-au-Prince harbor to ensure Haiti's compliance.

Although the amount was eventually reduced to $90 million gold francs, an amount equivalent to $20 billion today, Haiti was paying off the debt until 1947, 143 years after independence. While the Haitian government demanded that these payments be returned, the French "responded by helping overthrow the government" in 2003.

During the plan for independence, revolutionary general Jean-Jacques Dessalines wrote a letter to President Thomas Jefferson in 1803, stating that Haitians were "tired of paying with our blood the price of our blind allegiance to a mother country that cuts her children's throats." Jefferson never wrote back

Instead, the United States imposed an embargo on Haiti soon after it declared independence and refused to recognize Haiti's independence until 1862. Despite everything, Haiti has maintained its independence ever since its revolution, although it was briefly occupied by the U.S from 1915 to 1934.