The Messed Up History Of Victorian Fashion

Fashion can get uncomfortable. People today might wear unstable high heels, cram themselves into shapewear, and rip out unwanted hairs, among many other practices. Even if you don't want to remake your entire body to fit someone else's idea of beauty, you've at least worn uncomfortable shoes or an itchy sweater for a day.

Thankfully, none of us have been forced into the messed up world of the Victorian era, especially its world of fashion. That's because, in some cases, Victorian clothing was literally trying to end your life. From arsenic-infused fabric to socks that would burn their patterns into your skin, clothing of this era presented a real hazard. Factory workers had to be extra-cautious around hazardous chemicals and incredibly dangerous manufacturing equipment.

Thankfully, as the BBC reports, the Victorian era also became known for its many reform movements. Some of these included building up protections for factory workers, while the Rational Dress Society specifically pushed for sensible clothing choices that didn't leave women at the mercy of corsets and crinolines.

So, next time you're regretting that too-small shoe purchase, remember that it could be much, much worse. At least your shoes probably won't kill you in the middle of the next party.

Some Victorian fabric was full of arsenic

During the Victorian era, scientists and manufacturers created synthetic dyes that produced beautiful, brightly colored fabric that was cheaper than ever before. Now, even the emerging middle class could afford richly colored clothing, wallpaper, and other textiles that brought new vibrancy into the home. Too bad it was killing everyone.

That may be an overstatement for some colors, but a certain shade of green really did prove deadly, The Arsenic Century reports. Known as "Scheele's green," this intense shade was created using a mixture of copper and arsenic trioxide. For manufacturers who regularly used the pigment during dye processes, silk flower construction, and even cake decorating, this could get dire. They developed open sores on their skin, experienced intense vomiting, and suffered from painful headaches and anemia. Even nonworking homebodies learned that they had been sickened by things as innocuous as their green wallpaper.

A low-level silk flower maker in London named Matilda Scheurer died because of exposure to this shade of green. According to Jezebel, her agonized passing was not only painful but also turned her eyes and fingernails green. By the time of her passing in 1861, activists had already learned the dangers of arsenic and were pushing to ban it from common use. Even after Scheurer's very publicized death and the action of other European governments, it took years for the British government to officially prohibit the use of arsenic in dyes.

Tightly laced corsets had serious consequences for Victorian women

For many years, the corset was a mainstay of ladies' undergarments. Women of all social classes would have been considered practically undressed without one. The garments encased a woman's torso with fabric reinforced first by whalebone, then by stronger and more rigid steel strips. According to the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, the addition of metal eyelets to the assembly in 1828 was a significant development in the history of the corset, though the little metal bits may seem inconsequential at first. The newer, stronger eyelets meant that corsets could withstand greater pressure than ever before, setting the stage for a controversial and potentially dangerous practice known as tight lacing.

Tight lacing itself was related to the growing desire for tinier and tinier waists as the era progressed into the 1840s, The Corset: A Cultural History says. As the era progressed, fashion dictated a more exaggerated hourglass silhouette, cinched in by a maid or friend rather viciously yanking corset laces ever tighter. Yet, the achievement of an itty-bitty waist had serious health consequences. Wearers constricted their lungs, making full breaths difficult if not impossible. Extended use may have atrophied some abdominal muscles. Meanwhile, tight corsets also appear to have had an effect on digestion, leading to small meals and some awkward bathroom visits for fashionable ladies.

Victorian hats were loaded with mercury

Victorian men were also subject to poor health and even possible death in the pursuit of trendiness. If they were craftsmen, their risk was even greater.

Take felt hats, National Geographic reports, which were usually made out of beaver or rabbit fur. To get the fur to stick together and form cohesive felt, hat makers brushed it with mercury. The substance did the job and then some. Mercury is a highly toxic substance, so much so that, eventually, workers' teeth fell out, their hearts and lungs began to fail, and their minds started to slip away. To be "mad as a hatter," as the phrase went, meant to develop the kind of paranoia and pathological shyness seen in mercury-addled hat makers. Wearers were kept safe by the linings of their hats.

Continued exposure to mercury could lead to neuromotor issues like trembling. According to Connecticut History, the town of Danbury, Conn., which was a center of hat making, was so notorious for causing this problem that shaking hat makers in the area were said to have developed the "Danbury shakes." It was only after many years of effort by activists and the Danbury hatters' unions that the state banned the use of mercury in 1941.

Large skirts sucked Victorian women into factory machinery

Workplace safety was, all too often, a foreign concept during the wildest days of the Industrial Revolution. While, according to the U.S. Department of Labor, conditions would eventually improve, and more stringent safety laws and labor reforms would be enacted towards the end of the 19th century, the road there sometimes got pretty gruesome. People working in cloth mills could inhale dangerous quantities of linen and dust, for example, while there was always the possibility of being sucked into machinery that lacked even the most basic shields or railings.

While it's clear that factories of the Victorian age needed plenty of work before they would be considered remotely safe, fashion-conscious workers also placed themselves in harm's way. Fashion Victims notes multiple stories of workers whose clothing got them caught up in dangerous situations while at work. For part of the era, large skirts supported by crinolines and hoops were fashionable but also made it far too easy for women to get dragged into machinery when their outsize clothes got too close to all those moving parts. Then again, even simple clothing could get you in trouble. In 1893, The Industrial Commission of Minnesota reported on a variety of sometimes gruesome incidents. In one, a lucky girl only had her skirt ripped off when it became stuck in industrial sewing equipment. Others weren't so fortunate.

Even Victorian shoe polish was ready to kill you

Sure, a person's bright green dress might drop enough granules of arsenic to kill a whole party's worth of people, assuming said people made the odd decision to eat up all their floor sweepings. Seamstresses might develop horrifying sores from arsenic in their fabrics, and hatmakers could be plunged into tremors and madness via mercury compounds. But, surely, wouldn't a simple shoe polish boy be safe from the deadly tide of Victorian fashion?

Of course not. According to Gizmodo, the fashion for shiny shoes could also occasionally kill people. Many polishes contained nitrobenzene, which spiffed up footgear quite nicely but could also make people pass out. If the polish was allowed to dry before handling, people were fine. Yet, if someone was impatient or regularly came into contact with the wet polish, they were in serious trouble. They could experience serious health issues like hypoxia, vomiting, and even death in some cases.

Consuming alcohol seemed to make the effects of nitrobenzene poisoning even worse, Fashion Victims says. One young man was so eager to go to a party that he put his shoes on while the polish was wet, getting some on his feet and ankles. After a few hours of drinking and kicking back with his friends, he vomited and passed out. His roommate later found the man dead, the victim of a lethal cocktail of alcohol and nitrobenzene.

Victorian skirts were massive fire hazards

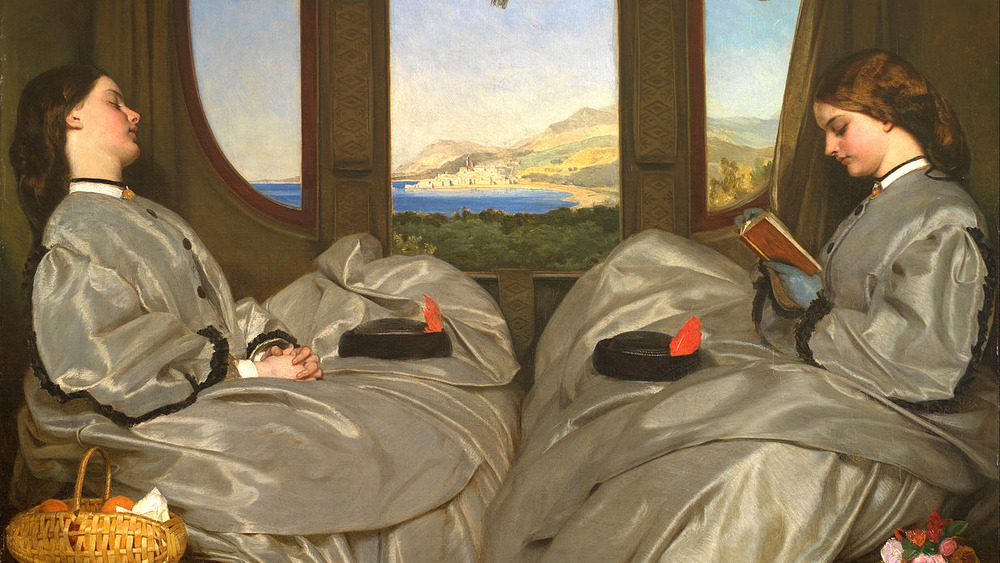

As the City University of New York points out, by the time the Victorian era was really underway, the ideal woman was a submissive "angel in the house." This ideal was also reflected in the fashions of the time with light, airy dresses made out of fabrics like open-weave gauze, tarlatan, and cotton muslin.

Unfortunately, says Racked, these ethereal textiles could also turn women into flaming infernos. This was a world where practically everything was lit by candles and gas lamps, which created a lovely sight at parties, where women in gauzy gowns seemed to glow in the soft candlelight. However, cotton is already a fairly flammable material. Meanwhile, those airy fabrics and hoop-supported skirts also allowed plenty of air to circulate beneath a dress, which could make a small flame grow out of control in seconds.

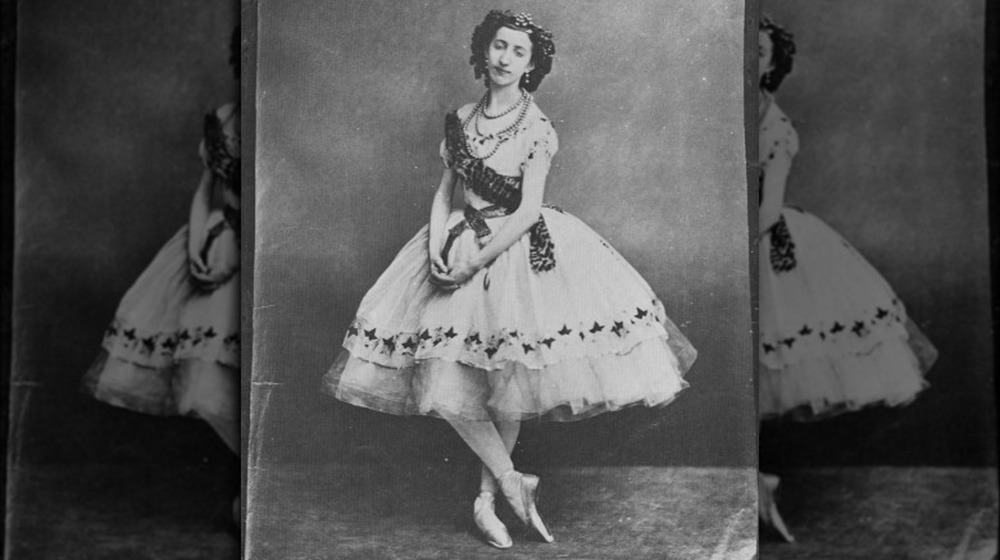

According to Ozy, ballet dancers were especially subject to these tragic accidents. Night after night, they danced in their flowing skirts right next to hot stage lights. They could choose to treat their costumes with fire-retardant chemicals, but it turned the fabric a dingy yellow. Some ballerinas skipped the step and danced in unaltered fabric, only to get too close to candles or lanterns, catch fire, and then die painful, lingering deaths.

Some Victorian makeup could make your face disintegrate

Makeup was a pretty touchy subject during the 19th century. The Oxford Student reports that Queen Victoria herself was very critical of its use, calling makeup vulgar and impolite because of its association with sex workers. Then again, there was a significant trend for "natural" beauty, which could be pretty unforgiving if someone had acne, a scattering of freckles, or even a bit of a sunburn. By the end of the 19th century, many people began wearing makeup again anyway, but it came with a cost. Face creams and other cosmetics could contain arsenic and lead. According to The Cut, lead-based cosmetics made skin severely dry and lead to intense abdominal pain before ultimately killing long-term users.

Even if someone committed to going au naturale, cosmetics-wise, they still got terrible advice. According to Atlas Obscura, advice writers like S.D. Powers recommended caustic ammonia to encourage hair growth or, confusingly enough, to remove unwanted hair. For those who wanted thicker eyebrows, Powers recommended no less than mercury. For fashionably dilated eyes, a lady might use drops containing deadly belladonna, though they could also go blind if they went too heavy on the stuff.

Even opium was floated as a solution for skin problems, according to The Ugly-girl Papers, though readers would have known it was addictive unless, as Powers writes, you simply took a bath to dispel that pesky dependency.

Victorian hairstyles could get you burned

Throughout the Victorian age, people often wanted their hair to be something that it wasn't. According to The Victorian Lady's Guide to Fashion and Beauty, that was frequently curly hair, manifested as anything from luscious waves to frizzy little bangs hanging out above someone's apparently fashionable forehead. To get that look, many people resorted to old-fashioned curling irons. These beauty tools were made out of actual iron and usually sat amongst hot coals to get up to temperature. If someone left them in the coals too long and incautiously applied to her hair, she may have been greeted not only with the smell of burning hair but with a large section laying in her hand and not on her scalp.

If a fashionista accidentally burned off a chunk of her hair, there were some solutions, but she may have wanted to pause before diving into the recommended treatments. Some, according to The Ugly-girl Papers, suggested a solution of ammonia to help it grow back. Never mind that ammonia can get pretty caustic and smells terrible even when properly diluted. According to author Mimi Matthews, body hair was sometimes removed with corrosive quicklime. Other compounds used in depilatory creams might be lye or even arsenic. For the more adventurous, hair follicles could be jabbed with needles or even killed off by an early and uncomfortable form of electrolysis.

Victorian fashion carried creepy crawlies

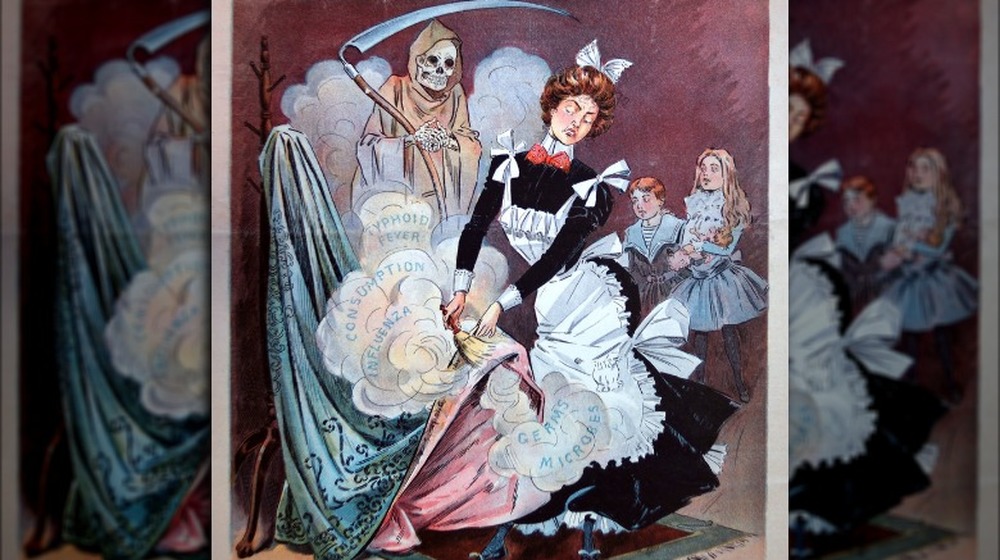

While many people like to romanticise the Victorian era, dreaming over the elaborate dresses and genteel way of life, that fantasy often conveniently ignores the grittier side of living during that time. For the vast majority of people, life as a Victorian was simply gross. While their clothes might have helped conceal some of their own bodies, things like long, trailing skirts could also pick up some unwanted travelers as the wearer moved about their daily life.

According to Fashion Victims, unfortunate soldiers demonstrated that battlefield diseases like trench fever and typhus could be spread by lice and fleas lodged in someone's unwashed clothes. One woman, the daughter of Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel, was even reported to have died of typhus because of one deadly garment. Her father had given her a riding habit made out of fabric that a seamstress had temporarily draped over her typhus-stricken husband.

It wasn't as if Victorians were ignorant of all this. Epidemiology for Public Health Practice reports that, by 1900, plenty of people believed that fashionable skirts could drag disease into the home, from tuberculosis to typhoid fever. Some arenas of the dress reform movement began to focus on fashion that helped encourage better personal and public health. This led to a few weird intermediary measures, says Ripley's Believe It or Not, like a metal skirt lifter that let its wearer hike their skirts up above street muck and also enjoy ladylike sports such as tennis.

Socks gave some Victorians chemical burns

The Victorians absolutely loved color. Though, of course, the great majority of photographs from that time are in black and white, stepping into a standard middle or upper class home of the period could have seemed like you were stepping into a rainbow. New dye processes meant that saturated, fade-resistant colors were more available than ever. People apparently wanted to show off. However, as some notorious socks proved, those newfangled dyes needed some refinement.

The socks in question first came to public attention in September 1868, The Case of the Poisonous Socks reports. That's when The Times, a London-based newspaper, published a report wherein a doctor had alerted police to the health effects of dyed socks. Orange dye in these pairs was made from a new type of acid that caused factory workers to suffer from sores all over their arms. Unfortunates who wore the socks could experience localized swelling so bad that, in one case, a man had to have his boots cut off. A contemporary report in The St. James's Magazine also pointed out the alarming fact that some dyes contained arsenic, a "baneful ingredient" that could sneak past chemical tests when paired with other dye compounds.

Gizmodo reports that not everyone had this issue. Some wore the socks with no problem, while others experienced serious chemical burns. It appears that the sufferers may have had more alkaline sweat that reacted with alkaline dyes, leaching the burning substance into their skin.

Tuberculosis became a fashion ideal for Victorian people

For an era that had a really scattershot approach to public health, the elevation of a devastating disease to a fashion ideal was one of the oddest fashion trends of the entire Victorian age. Charlotte Bronte may have written that it was a "flattering malady," as Hyperallergic reports, but it was truly devastating. Tubercular patients were wracked by fevers, starvation, and coughed up phlegm and blood.

Yet, as enough onlookers wiped the bloody coughing and diarrhea from their memories, tuberculosis became trendy. That's because disease victims also became pale and languid, Smithsonian Magazine says. They also sported dilated eyes that, to some, appeared to sparkle. Sufferers also occasionally sported rosy cheeks, interpreted not as the flush of a deadly fever but as a lovely, rosy bloom on top of delicate skin.

Historians have since connected popular Victorian fashions to this odd emulation of people on their deathbeds. Tightlacing, in which women cinched their corsets and waists to ever-smaller circumferences, may have been linked to the emaciated look of an end-stage tuberculosis victim. So, too, was the trend for pale skin and rosy cheeks and lips, sometimes helped along by a bit of makeup.

Combs could spontaneously combust on a Victorian dressing table

Let's say that there was a hypothetical Victorian fashionista that tried to do everything right. She stayed away from makeup, since it was full of lead and arsenic and made your skin basically fall apart. The queen hated the stuff, anyway. She wore sensible ball gowns that wouldn't burst into flames the moment she looked at a gas lamp. She was a devotee of the aesthetic dress movement, which Ohio State University reports was a push to get women into looser, more "natural" clothing that didn't require tightly laced corsets.

Unfortunately, she forgot about her comb. As it sat on her dresser, maybe sitting for just a minute too long in the sun, it burst into flames.

The tiny inferno was because of celluloid. This early plastic was a popular and inexpensive material for combs and many other products, Smithsonian Magazine says, replacing expensive ivory. However, celluloid is also highly flammable. Consumers reported that items made from it tended to burst into flame, almost without warning. Celluloid products could even explode, as when billiard balls hit each other and dramatically burst apart. It was even worse for manufacturers. In 1909, The Day reports, nine workers died in an explosion and fire that tore through a Brooklyn comb factory.