How Life Would Be Different If The Great Depression Never Happened

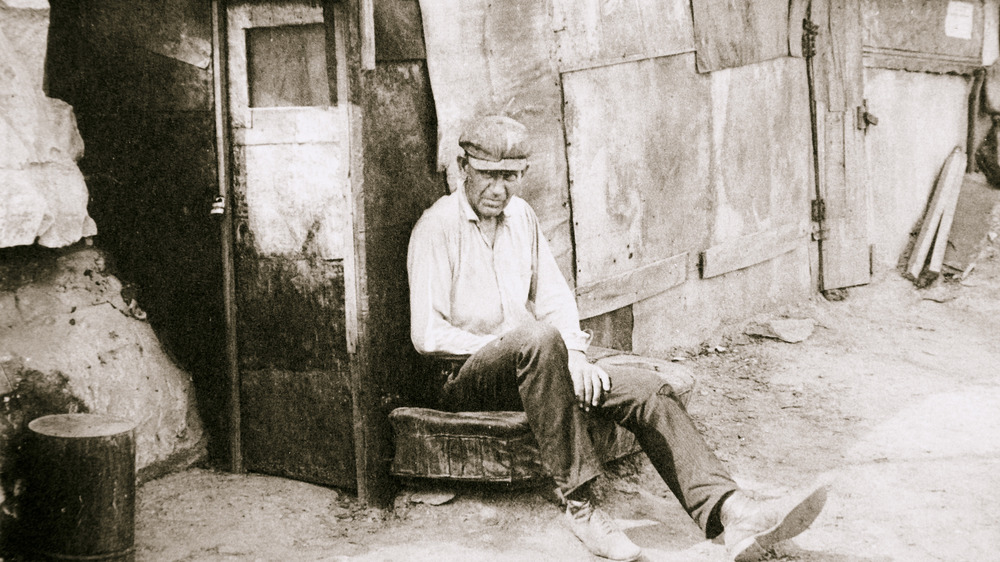

Between 1929 and 1939, the entire industrialized world was caught in the grip of the biggest financial crisis in history. It started with the crash of the United States stock market, and soon, the nation was spiraling out of control. By 1933, History says that the depression had reached the worst it would get — half the banks in the country had collapsed, and more than 15 million people were without work.

Herbert Hoover was president in the beginning, and his response was less-than-stellar. He pretty much said that it would sort itself out. That's not what people wanted to hear, especially when so many were homeless, starving, and worse.

By the time Hoover started trying to get the banks up and running, it was too little, too late. In 1932, Franklin Delano Roosevelt won the presidential election in a landslide, and it was then that he famously declared, "The only thing we have to fear is fear itself."

Roosevelt started getting things done — legislation was passed to help stabilize the economy, projects were formed to create jobs, and his New Deal overhauled the country into something much more resilient. While the Great Depression was horrible for those who lived through it, the U.S. would look very different today if it hadn't happened.

There's some major companies that wouldn't exist

When the stock market crashed and banks started failing, many people lost everything. More than their savings disappeared, jobs disappeared, too. But here's the weird thing — according to Forbes, there were seven families who not only started companies during the Great Depression but were also hugely successful. They were so successful, in fact, that they're worth a combined $31.9 billion today. Economists argue that the kind of entrepreneur who starts a business at a time when the financial landscape is so dire is something special. They're called "survivalist entrepreneurs," says University of California, Los Angeles, professor Ivan Light, and who are we talking about?

For starters, it was George Jenkins who quit his job at the grocery chain Piggly Wiggly to start his own store in 1930. That's Publix, and they now do $29 billion in annual sales.

Then there's the McKee family, who started selling cakes from their car. That company grew to be Little Debbie. The Gallos crushed grapes and made wine in their shed, and the E&J Gallo family is now worth $9.7 billion. J.R. Simplot worked a patch of land in Idaho and started selling what his family could eat — after perfecting a freezing process he started selling fries — they now supply a third of the country's fries.

Also on the list are Columbia Sportswear, Hess oil and gas, and the Stephens investment group.

Projects of the Civilian Conservation Corps wouldn't exist

The 1910 essay, "The Moral Equivalent of War," suggested that instead of conscripting the young men of a nation and training them to be soldiers, they could be recruited instead to work on various infrastructure projects. That idea was put into place in Europe after World War I, and the National Park Service says President Franklin D. Roosevelt took a page from that playbook when he created the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC).

It was a massive success, and PBS says throughout the 1930s, around 3 million men — all unmarried and all between 18 and 25 years old — were hired for $1 a day. They lived in work camps across the country, were given classes in things like engineering, first aid, and auto repair, and if it wasn't for their hard work, the landscape would look very different.

Today, it's estimated that half of the trees ever planted in the U.S. — around 2.3 billion of them — were planted by CCC workers (like the ones pictured). They developed most of the nation's parks, building roads and hiking trails to make them accessible, along with visitors' centers, amphitheaters, swimming pools, and other recreational facilities. They built roads like the Blue Ridge Parkway (via Roadtrippers), repaired bridges, and even built dams and created lakes.

Gradually, the CCC came to an end at the beginning of World War II, when the nation's young men were needed for another sort of service.

Housing maps would look very different

In 1968, the Fair Housing Act made it official — it was illegal to discriminate against anyone trying to rent, buy a home, or finance a purchase based on race, nationality, religion, skin color, or sex. (That was expanded to include family status and disability in 1988, says Investopedia.)

The reason that federal law and those protections are in place today goes back to the Great Depression. In 1917, the Supreme Court outlawed city ordinances that had been put in place to ensure some areas remained segregated. According to ThoughtCo., those were replaced by "racially restrictive covenants," which were basically agreements between area property owners that resulted in the same segregation.

Fast forward to 1934. That's when the federal government first got involved with housing schemes, thanks to the creation of the Federal Housing Administration (FHA). It was part of Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal, and the idea was to rebuild the housing market and get the mortgage system straightened out. It didn't work as planned, and the FHA almost immediately introduced redlining.

Redlining is the process of color-coding housing grids to determine where the most secure investments would be, and it was absolutely race-based. An area only got a green designation if they were free of "foreigner or Negro." At the other end were red neighborhoods, which were largely populated by minorities. Redlining still continues today, but now, at least there's legal protections put in place to try to stop it.

Alcohol is legal

Prohibition is one of those things that, in hindsight, was a pretty dumb idea for all sorts of reasons — including the fact that CNBC notes that during the run of Prohibition, the federal government not only lost an estimated $11 billion in revenue but also spent more than $300 million to enforce the laws.

That's the opposite of good business sense, and once the Great Depression hit, more and more people started turning to the "shadow economy" created by the now-illegal liquor trade. On the plus side, doctors made out like bandits and prescribed about $40 million in "medicinal" whiskey.

The 21st Amendment put an end to Prohibition in 1933, and while there were a slew of reasons it was ultimately repealed, the Great Depression was a major one.

According to Garrett Peck, author of The Prohibition Hangover: Alcohol in America from Demon Rum to Cult Cabernet (via History), the Great Depression allowed anti-Prohibitionists to add another layer onto their arguments, and it was one that swayed well-known Prohibition supporters. When Prohibition kicked off, it put around 250,000 people out of work — and they were jobs that were desperately needed during the Depression. When Franklin D. Roosevelt ran for president, he made it clear that making booze legal would "increase the federal revenue by several hundred million dollars a year" and put people to work... so it was a win-win.

School lunches wouldn't be provided

The federally supported school lunch program is a huge deal. According to the Department of Agriculture, the National School Lunch Program supplies children from low-income or food-insecure families with free or reduced price lunches. In 2019, they served almost 5 billion of those lunches, with about 75% being free or sold at a reduced price.

And that goes back to the Great Depression.

By 1900, most states had laws requiring parents to send their children to school, and once children from all walks of life were eating in a cafeteria together, it was clear who was struggling and who wasn't. Some cities — like Boston and Philadelphia — started school lunch programs funded by private welfare organizations, but Time says that it wasn't until need became widespread during the Depression that the federal government got involved.

Under the auspices of the New Deal, the federal government started buying farmers' surplus crops. Then, they hired scores of people to start cooking and serving students across the country, and it was a win for everyone involved. The program struggled through the lean years of World War II, but in 1946, the National School Lunch Act became permanent.

Banks and investments would be a lot riskier

Every time anyone steps into a bank, they're greeted by signs advertising that institution's connection to the FDIC. It's such a commonplace sight these days that it's easy to forget it's a big deal.

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation oversees the operation of banks, and it also insures deposits that customers make — usually, says Investopedia, up to $250,000 per account. It was created alongside the Banking Act of 1933, and it was designed to prevent exactly what had happened to cause the Great Depression — widespread bank failure and insolvency. (Pictured are customers at a bank in Cleveland, trying to get their money, circa 1933.)

The inner workings of the banking industry and the international economy is enough to make a brain hurt even if it has a degree in advanced calculus, so let's keep this simple. Basically, the act separated commercial banks (where checking accounts are born) from investment banks (where long-term investments go). Then, the FDIC collects money from banks across the country and puts it into a pool, and if there are losses, that money is used to cover them.

And according to History, it has definitely paid. Around the 2007 financial crisis, 25 banks failed — but this time, there were safeguards in place.

Many employees wouldn't have the protection of a union

Labor unions have been around for a long time — according to PBS, American labor unions got their start with the post-Civil War National Labor Union and then the Order of the Knights of St. Crispin, who were a group of cobblers that protested the industrialization of the shoe industry.

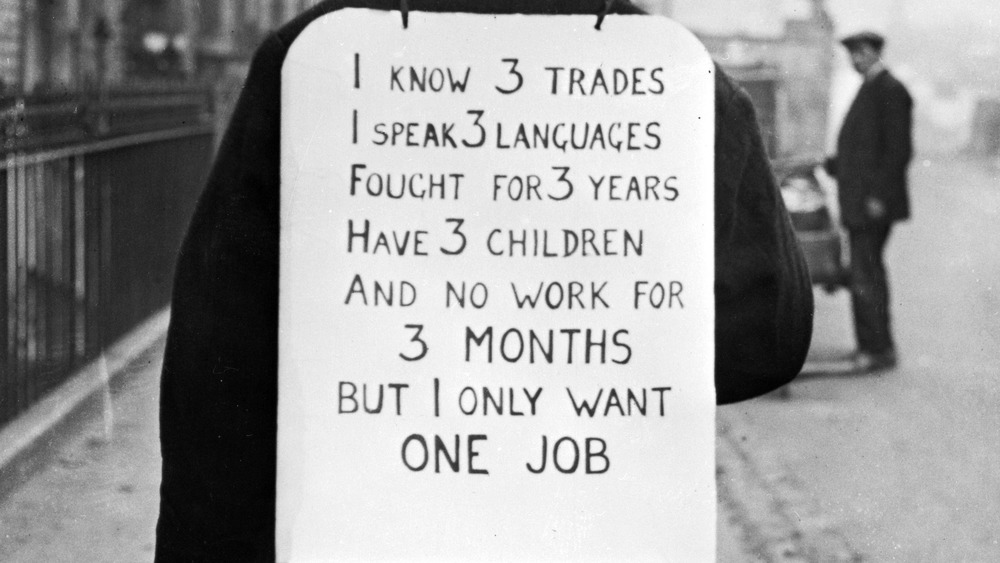

At the time of the Great Depression, it looked as though labor unions were actually going to go the way of the dodo. According to the Library of Congress, membership dropped by 2 million between 1923 and 1933, and a large part of that reason is that most labor unions still represented skilled craftsmen — like those cobblers — instead of those who were working in fields of mass production and industry.

As part of his way to stabilize the job market and make industry more fair for workers, President Franklin D. Roosevelt included a few pro-union laws in the New Deal. In 1933, they passed the National Industrial Recovery Act, which allowed unions to make deals on behalf of their members. That was followed by the National Labor Relations Act (or Wagner Act) in 1935, which forced all businesses to deal with any union supported by the majority of their employees. With this newfound power, the Congress of Industrial Organizations broke off of the American Federation of Labor and started representing unskilled laborers — workers who, until then, had never had an advocate.

The surprising impact of the Tennessee Valley Authority

The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) has a fascinating history, and it's one of those organizations that prove just how interconnected everything can be — no matter how unlikely it might seem. It was originally founded in 1933, and according to History, the idea was that it was going to create jobs for those working in the seven states of the Tennessee River Valley. Those newly employed people would, in turn, develop commerce, agriculture and industry, oversee the hydroelectric power supplied by the Wilson Dam, and care for the land. They were also given permission to develop more reservoirs, dams, or power plants as the need arose.

There were a lot of people who started screaming about socialism, but the development of the TVA — and the entire area — ended up being incredibly fortuitous... especially by around 1941.

The TVA's most obvious contribution to the war effort was power. Their power stations ran places like Nashville's A-31 bomber factory and Knoxville's Aluminum Company of America (Alcoa) factory, who supplied a huge amount of material for the military. They also powered another area — Oak Ridge, which was part of the Manhattan Project.

The TVA also supplied nitrate for munitions and fertilizer for crops in the U.S. and other Allied countries, and their mapping department also perfected the techniques used in making maps for the Allies' military. Without their contributions to the war effort, there's no telling what consequences would have been reflected in today's world.

Projects of the Public Works Administration wouldn't exist

President Franklin D. Roosevelt was inaugurated in March of 1933, and he didn't waste any time in getting down to business. Living New Deal says that it was just a few months later — on July 8, 1933 — that he chose the man he wanted to head up the Public Works Administration (PWA). He then gave Harold Ickes $3.3 billion — the most ever given to a public works project in the country's history — and tasked him with funding projects that would modernize the nation's infrastructure, while putting a whole lot of people to work.

By 1939, the program had funded 34,000 projects, and that year is important. After that year, the PWA's focus changed to military projects (which included the construction of the aircraft carrier Yorktown, a name that World War II buffs will recognize). They were rolled into the Federal Works Administrator in 1943, but before that, they built structures like Key West's Overseas Highway (that connects the Florida Keys to the mainland), the San Francisco Mint, the Grand Coulee Dam, Reagan National Airport, New York City's Triborough Bridge, San Francisco's Bay Bridge, DC's Federal Trade Commission Building, and the Ellis Island Ferry Building, among thousands of others.

PBS says that communities were able to submit proposals for projects, and while not all were accepted — some wanted moon rockets and moving sidewalks — PWA projects changed the landscape of the country.

Social Security wouldn't be a thing

In 2020, the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities estimated that one in six U.S. citizens — around 64 million people — received some kind of benefits from social security. It doesn't just support retirees, it's also given to children who have lost their parents, and it also insures workers in case of accidents or severe disability.

And it was signed into law on Aug. 14, 1935, by President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

According to the Social Security Office of Policy, the idea of social security had its roots in Germany in the 1880s, where workers paid into a program that would protect them in the case of things like disability and prolonged illness, as well as provide for them in old age. The problems that wage insurance solved — particularly lost income due to death, illness, disability, and retirement — were a major problem even before the stock market crash, and historians argue that it was the Great Depression that finally added enough fuel to the fire to get reform enacted.

Over the course of the Depression, the plan went through a few forms. In 1939, amendments to the program created benefit status for survivors who had lost the family breadwinner, and benefits became more readily available to younger claimants.

There would be a lot more gold out there

Humans have loved shiny things for a long time, and according to The Balance, gold has been used as currency since at least 600 B.C.

Early on, America operated on what's called the gold standard, which means that the economy relied on a set price for buying and selling gold, which then dictated how much value paper money had (via Investopedia). It's one of those things that's absolutely headache-inducing, but don't worry, it changed with the Great Depression.

That's because the price of gold started rising, and people were both trading in paper money for gold, then hoarding that gold because they no longer had any faith in banks whatsoever. That's why President Franklin D. Roosevelt closed banks in March of 1933, and put a stop to gold trading. Banks were required to turn all their gold over to the Federal Reserve, and a month later, American citizens were ordered to do the same. As a result, they got paper money, and Fort Knox accumulated what was the world's largest stash of gold.

Fast forward a few months, and Roosevelt made another proclamation — absolutely no one was allowed to own gold. The Foundation for Economic Education says that marked the end of the U.S.'s use of the gold standard, and even though it's perfectly legal to own gold today, it's safe to say that without Roosevelt's crackdown, there would be a lot more floating around.

Chocolate chip cookies might not have taken off

Who doesn't love a good chocolate chip cookie? They're right up there with apple pie and baseball when it comes to things all-American, which kind of makes it fitting that they came from a time of struggle and hardship.

They're a little unique in that people know exactly who invented them — Ruth Wakefield, proprietor of the Toll House restaurant in Whitman, Mass. She whipped up her first batch in 1937 and contrary to popular belief, Carolyn Wyman, author of the Great American Chocolate Chip Cookie Book, says (via The New Yorker) that it wasn't a happy accident at all, and she knew exactly what she was doing.

And here's the thing — they also say that the chocolate chip cookie was exactly what the nation needed. Over the next few years, chocolate chip cookies got insanely popular, showing up in all kinds of cookbooks and in all kinds of places. For nearly a decade by that point, people had been going without. The chocolate chip cookie was rich, sweet, decadent, and chocolatey, all in a super affordable little package that gave those fortunate enough to bite into one a taste of what they had been missing — and, just like today, they're an accessible reminder that there are good things in life.