The Criminal Organization Behind The American Mafia

Glamorous, wealthy mob bosses with roses placed on their lapels, horse carcasses left in your enemy's bed sheets, shiny sexy flapper girls with extra long cigarette holders — at least that's how the movies like to portray the Mafia.

But the reality of how the Mafia was born in America is a bit dirtier, a lot uglier, and even more ruthless. Even Martin Scorsese's gritty Gangs of New York was glossy in comparison to what historical records indicate.

It all started when a handful of Sicilian immigrants landed in New York Harbor in the mid-1800s — not necessarily seeking a new life in the land of plenty but to escape from their heinous crimes. They settled in the Five Points in lower Manhattan, which during most of the 19th century was considered a lawless slum. The area has since been built over, like a slick band-aid on a seeping national wound.

Forget what you learned from The Godfather, except perhaps what Don Vito Corleone taught us. Revenge is a dish best served cold in the Mafia.

The Sicilian mafia: an origin story

Sicily is historically known for being a bit of a misfit island off the coast of Italy, between North Africa and the Italian mainland. Sicily has a long history of being conquered by everyone from the Romans to the Spanish through the centuries. Residents of the island eventually got sick of it and began to form groups or "clans" to protect themselves due to tense intersectionality amid occupying forces. They even developed their own small, private armies known as "mafie" and carried out their own justice and retribution.

These mafie not only acted as judge and executioner but also extorted funds from landowners. The Catholic Church was even in cahoots with these groups, as they relied on the clans to keep an eye on their property holdings. By the 19th century, the official Sicilian Mafia was born.

The Sicilian Mafia came to America's shores when Giuseppe Esposito and six henchmen escaped to New York after the murder of two prominent political figureheads and 11 wealthy landowners in Sicily. Esposito took refuge in New Orleans from there, where he was eventually caught and sent back to Italy.

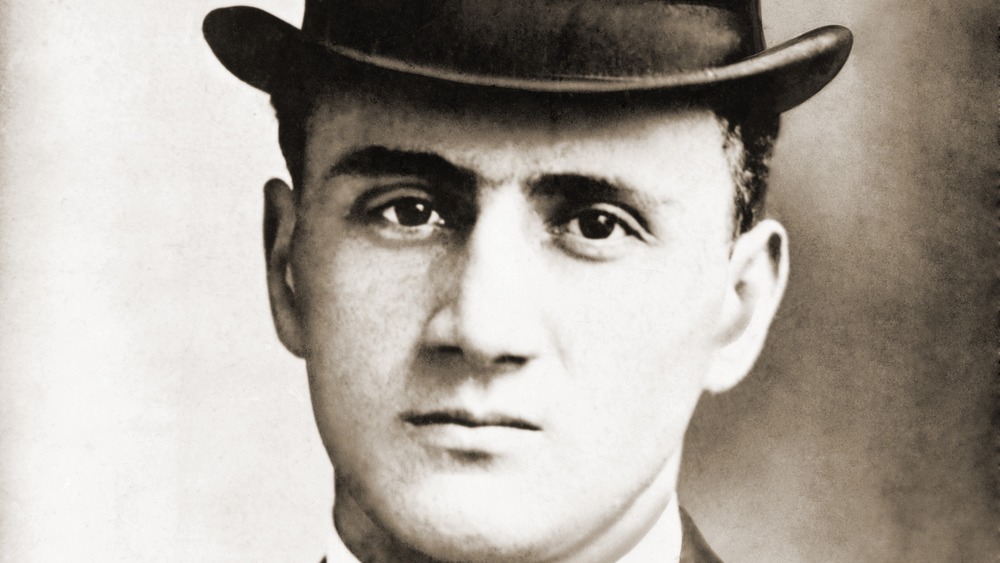

Paul Kelly

Paul Kelly, the eventual founder of the Five Points Gang in lower Manhattan, was born in Sicily by the name of Paulo Vaccarelli. He would successfully recruit nearly 1,500 men into his gang. Among his recruits are some of today's household name gangsters, including Al Capone and Lucky Luciano. Kelly wasn't shy about throwing his weight around town by facilitating voter fraud and intimidation to make sure political candidates who were sympathetic to the mob got elected. But Kelly was more than just a mobster.

He got his start in the Big Apple as a bantamweight boxer. Kelly had a knack for the sport and eventually turned pro, which is when he swapped his birth name for a more Irish-sounding one. Italians were, sadly, seen as lower class at the time. Kelly saved his boxing money and invested in a string of brothels within the Italian immigrant district. Kelly was also fluent in multiple languages. His extracurricular talents allowed him to rub shoulders with the city's elite.

Kelly had a dangerous rivalry with Jewish gang leader Monk Eastman. The gangs often went at it, and the Bowery was their dividing line — where the Five Points Gang gained control of the west and Eastman's gang had control of the east.

Kelly was shot by two of his own gang members in 1908, but he survived and died of natural causes at the age of 57. The Five Points Gang remains the last dominant street gang in New York, according to History Collection.

The Five Points gangs are born

If you've seen Gangs of New York, you've had a taste of what the Five Points of New York City may have been like in the mid-19th century. Italian, Irish, and Jewish gangs duked it out for years in the most notorious neighborhood of lower Manhattan. The neighborhood fostered criminality, protecting asylum-seeking criminals from corrupt officials. But that didn't stop the powerful and corrupt from utilizing these criminals for their own gain. This cyclical system kept the gang lifestyle churning.

Charles Dickens himself called the neighborhood "a world of vice and misery." Sewage and rats poured onto its cobblestone streets, pigs roamed freely, and families crammed into tiny dark spaces for shelter. "The whole neighborhood just stank," historian and author of the book Five Points Tyler Anbinder said.

It was also dreadfully dangerous. The Old Brewery of Five Points averaged a murder a night for more than 15 years.

Clearly, this was the perfect atmosphere for Sicilian-inspired gangs to make their start. But they would have to pay their dues in a few gang wars before they would prove their dominance. In the mid-19th century, the Irish basically ran Five Points. A slew of Irish immigrants came to New York after the potato famine in 1840, and there were a number of gangs for the Italians to compete with at the time — the Bowery Boys, the Dead Rabbits, the Plug Uglies, the Short Tails, and the Slaughter Houses, to name a few.

The gangs and political corruption

Paul Kelly got his gang of hooligans into the underbelly of the political scene by finding out who could be bought. They made allies with the Democratic Party, where they assisted in election wins by threatening voters and messing with voter lists and ballot boxes in the era of Tammany Hall.

Some gang leaders even became politicians themselves. John Morrissey, who led the Irish gang the Dead Rabbits, became a United States congressman, largely due to his influence concerning Tammany Hall's political circle.

All of the gangs within the Five Points used their political prowess to their benefit, which, as you can imagine got a bit messy in the voting booth. Some gangs even formed legitimate political clubs that met on nights and weekends. "They would fight at the polls and sometimes beat up their opponents, but not just for fun or plunder," historian Tyler Anbinder says. And the fighting worked. Once the gang was able to get their candidate elected, that candidate was indebted to them. Minus the fisticuffs, it's really not much different from how political lobbying works in U.S. politics today.

These gangs quite literally owned lower Manhattan. But it's nothing the Southern District of New York couldn't handle.

The gang's rivals

The Bowery Boys, Roach Guards, Dead Rabbits, the Eastman Gang — the Five Points Gang had their fair share of nemesis groups that they clashed constantly with. Among them, the Bowery Boys are probably the most well-known. Unlike their counterparts, they made it a point to dress in fancy clothes and held legitimate jobs. The Boys acted more like a political club, much like the Five Points gang, and also intimidated voters at polling places. In return, they received money and special treatment in their district.

The Dead Rabbits were a crew of Irish Catholic immigrants and among the most feared gangs in lower Manhattan in the mid-19th century. Their speciality was pick-pocketing, theft, and fisticuffs — particularly with their main rivals, the Bowery Boys. It's worth noting that women were welcome in this gang. The infamous "Hell-Cat Maggie" brawled with the Rabbits, and legend has it that she "filed her teeth to points and wore brass fingernails into battle." Also known as the Roach Guards, the Rabbits mostly drew the line at petty crime, but the famous bloody street standoff of July 4, 1857, was initiated by their hands.

The Eastman Gang, led by Jewish mob man Edward "Monk" Eastman, rose to power in the late 19th century with around 1,200 members. They concentrated on running brothels, drug rings, and murder-for-hire operations.

Each of these gangs proved threatening to the Italian Five Points crew, but they barely survived past the early 20th century.

The gang members' rising stars

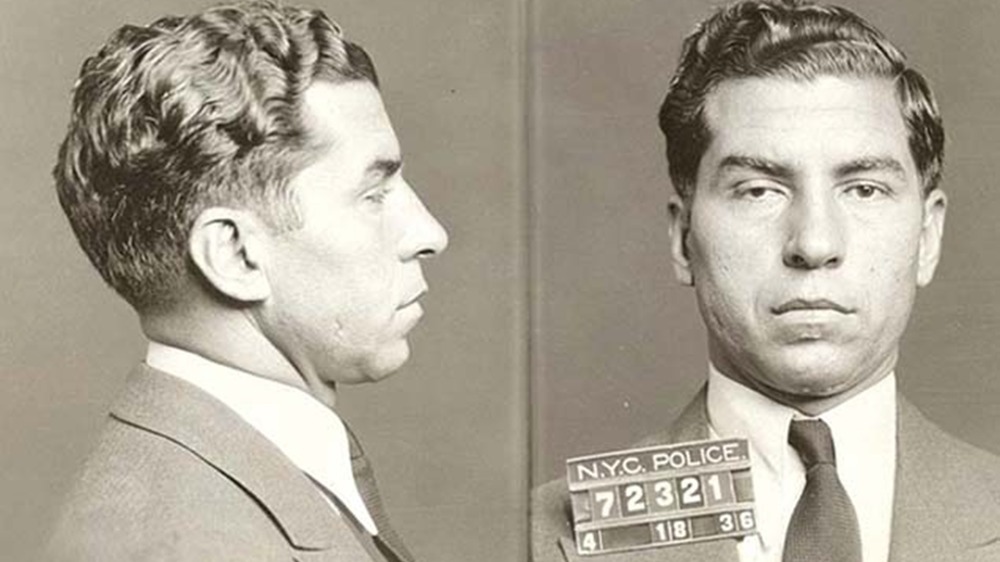

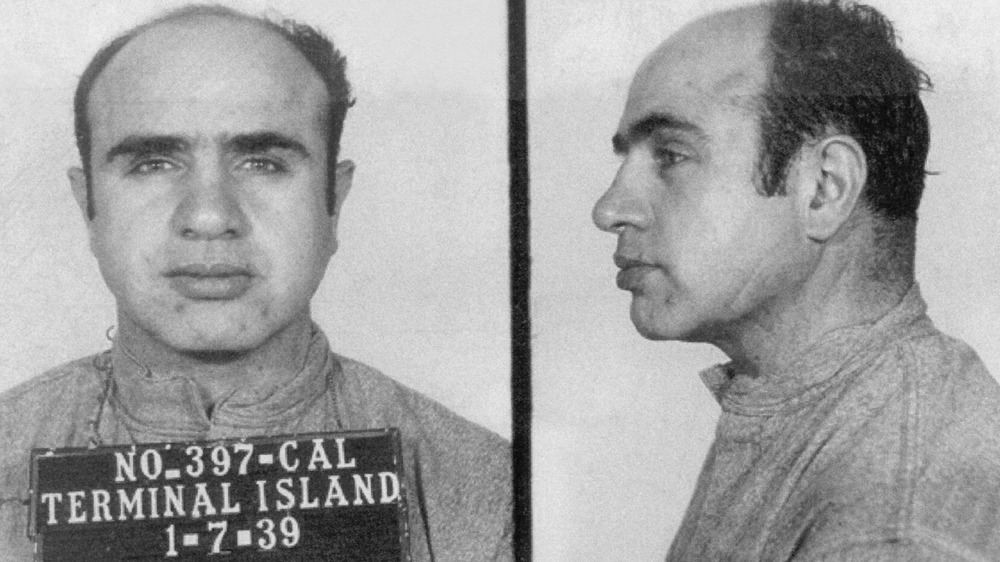

Both Al Capone and Lucky Luciano got their start in the Five Points gang under Paul Kelly and would both become threats in their own right later in Chicago and New Orleans.

Capone, or "Scarface" if you were friends, was born in 1899 in Brooklyn, and then-Five Points gang leader Johnny Torrio, along with Kelly, took the baby gangster under his wing. Capone quit school after the sixth grade to go pro. Little did Torrio know that he would become the most infamous gangster in American history. Capone got his infamous nickname by suffering a gash wound on his face after a fight in a brothel. Capone was a smooth operator and would learn to make nice with the media, giving off a legitimate businessman persona. He brought that swagger to Chicago, but things got ugly in 1929 when rival gang violence led to the infamous St. Valentine's Day Massacre.

His fellow gang classmate, Charles "Lucky" Luciano, moved with his family from Sicily to New York at age 10. He got his nickname "Lucky" by apparently miraculously surviving a ton of life-threatening beatings. Luciano became a member of the Five Points gang at age 14, where he and Capone became good friends. He was also known for protecting Jewish teens for five to ten cents a week.

But things were about to change for these budding mobsters with the ratification of the Eighteenth Amendment — leading to the dreaded Prohibition era.

The mafia and prohibition

The Mafia made a fortune bootlegging alcohol during Prohibition, where they took hold of power in America by working underground and outside of the law. It turns out making liquor sales illegal didn't stop people from drinking. How strange.

It was a match made in heaven for the Mafia. Their resumes already covered skills like smuggling, money laundering, and bribing public officials. Before Prohibition, they were merely a criminal organization. But mix lawlessness with demand, and you've got palpable power. And with money came fancy lawyers to finagle the Mafia out of trouble.

"They had to become businessmen," says Howard Abadinsky, a criminal justice professor at St. John's University and author of Organized Crime. "And that gave rise to what we now call organized crime."

Unfortunately with that power also came violent territorial warfare. Crime syndicates don't like to share profits. The gangs took over American cities to the point where law enforcement struggled to keep order. Once Prohibition was repealed in 1933, the Mafia had to branch out into other ventures like drug trafficking and illegal gambling.

Fascism in Italy and new recruits

The 1920s saw the rise of Benito Mussolini, and he clashed big time with the Sicilian Mafia, causing a hoard of Sicilians to immigrate and take refuge in the U.S. First stop was New York City, where the American Mafia was already well established, and prohibition was underway.

Mussolini's decade-long feud with the Mafia began with an insult. When Mussolini went to Sicily as prime minister in 1924 for a publicity stunt, he brought his large entourage along. This apparently upset the mayor of Piana dei Greci, who happened to be Don Francesco Cuccia, a mafioso. "You are with me; you are under my protection. What do you need all these cops for?" he apparently asked Mussolini.

This exchange was the last straw for Mussolini, who already had his sights on the lawless Mafia. Both parties left insulted, which led to Mussolini refusing Cuccia's hospitality, and Cuccia told his constituents to boycott the prime minister's public address. As an aspiring dictator, Mussolini simply could not let a rogue group of powerful men undermine his authority.

In 1926, Mussolini introduced a bill in the Italian Chamber of Deputies that called for the suppression of the Mafia in Sicily. His police arrested hundreds of mob members in widespread raids, and many were convicted for various crimes. The message was quickly received that they were no longer welcome in their own country. So the Mafia journeyed across the Atlantic where they would be in good company.

Branching out to Chicago and New Orleans

Lucky Luciano originally took refuge in New Orleans when he arrived from Sicily because he knew he'd be in good company. New Orleans has a deep-seeded mafioso history. Some experts believe it may have been the original center of the Mafia.

After the civil war, many freed slaves understandably left the antebellum South, forcing Louisiana to actively recruit farm workers elsewhere. This prospect attracted nearly 300,000 Sicilians between 1884 and 1924 to the Big Easy. America's first official Mafia war took place in New Orleans' Little Palermo when Raffaele Agnello, the original godfather of the city, and fruit importer Joseph "J.P." Macheca duked it out over their workers. Turf wars escalated, leading to a superintendent of police, David O. Hennessy, being shot and killed by the New Orleans Mafia. Mass hysteria ensued, resulting in approximately 250 Italians arrested. A mob stormed the jail they were being held in, lynching 11 Italian men.

Al Capone, on the other hand, traveled to Chicago, where he became the leader of the Chicago Outfit during Prohibition.The Outfit became the single most powerful underground organization for many years after Prohibition ended. But the FBI was onto them at this point. And the mobsters were also tracking the FBI.

The Mafia, police, and the FBI, oh my

The FBI would have a long, strange relationship with the Mafia. By the mid-1920s, Prohibition had attracted many more people into the gangster business. In Chicago, an estimated 1,300 different gangs spread through the metropolis.

Thanks to weapons like Tommy guns, law enforcement found themselves outgunned and unprepared to take the Mafia on. It was truly a lawless time in Chicago, and Al Capone was at the helm of the chaos.

J. Edgar Hoover began his tenure as head of the FBI just a few years before Prohibition, and he was determined to crack the whip on the incessant lawlessness plaguing the country. Fingerprint evidence was introduced around this time as part of modernizing the bureau, making it easier to catch criminals and exonerate innocents. Finally, the FBI had the mob on the run. Ironically, it was a different Hoover that was responsible for Al Capone's eventual demise. President Herbert Hoover.

President Herbert Hoover had become increasingly concerned with the state Chicago found itself in, and he had the federal government make it their mission to catch Capone. In 1931 they were successful in Capone with tax evasion, sending him to the slammer and thus ending his reign of terror as king of the Chicago Mafia.

Johnny Torrio's Outfit

Al Capone may have been the famous name that lingered within the Chicago crime circuit, but it was Giovanni "Johnny the Fox" Torrio who founded the Chicago Outfit and learned everything he knew from Paul Kelly as his right-hand man.

Torrio made his money in his own operation, which specialized somewhat in prostitution and opium trafficking. But his main cash line was from gambling. He kept himself above board by being involved in legal businesses like billiards. Torrio was the man responsible for hiring Capone, and the rest is history.

He and Dean O'Banion made a gentleman's agreement to become business partners, which allowed them to run the streets of Chicago between their two gangs. O'Banion, however, was no loyalist. He and his men had been successfully and secretly hijacking the Outfit's liquor trucks. When Torrio found out, many believe he was the one who ordered a hit on O'Banion. O'Banion's crew ambushed Torrio in retaliation outside of a grocery store, shooting him four times. Torrio miraculously survived the incident but got sent to jail after his recovery.

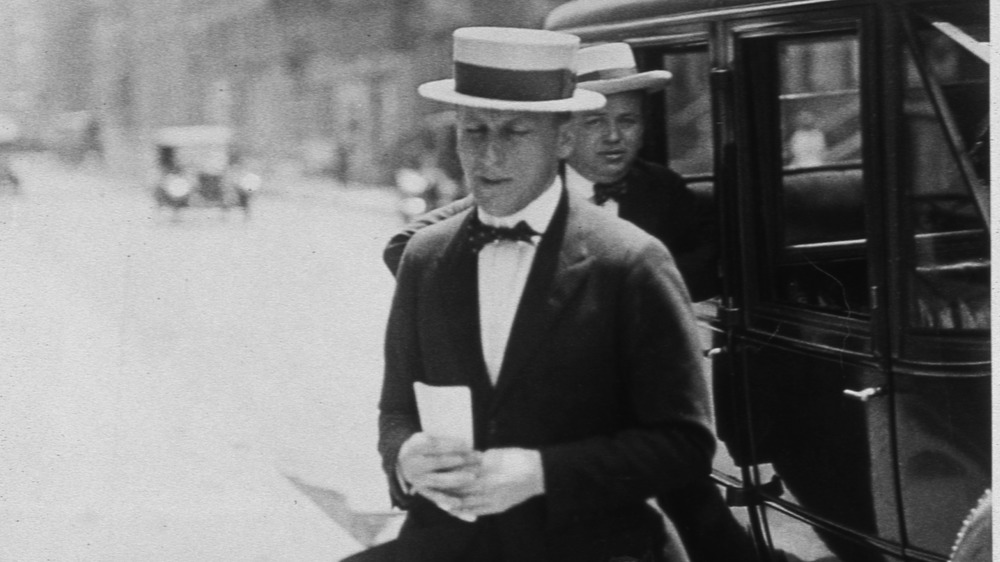

Arnold Rothstein and international expansion

One of the most notorious gangsters in Mafia history, Arnold Rothstein, is rumored to have fixed the 1919 World Series and benefited handsomely from it. He was also once paid half a million dollars to mediate a gang war. More importantly, he was the sophisticated businessman of the Italian-American Mafia crew and helped them expand illegal opportunities internationally. He made the Mafia less of a gang of hoodlums and more of a legitimate corporation.

Rothstein became filthy rich, with a fortune growing to around $50 million, which allowed him to evade persecution by paying off judges and police officials. He is rumored to have always carried around $200,000 in pocket money at all times.

Ultimately it was businessmen like Rothstein that moved the American Mafia forward. Like most Mafia leaders, he would meet a bloody end, but these outliers are widely responsible for cementing a system of underground control that still lasts to this day.