Here's How The Civil War Changed Christmas For America

Christmas feels like it's been around forever. (Especially around December 27, it really, really starts to feel like forever.) Every year, we're bombarded with Christmas carols and decorations starting in September, then the Santas and reindeer and Christmas trees kick off in — hopefully — the post-Halloween chill. And it's always been like that... right?

Strangely, Christmas as we know it today is a fairly recent creation, and the reason why it's celebrated in the way that it is has a lot to do with the American Civil War. Who would have thought, right?

Even the widespread practice of saying December 25 is Jesus's birthday is a fairly recent addition to the holiday mythos... relatively speaking. Bible Archaeology says that the actual Bible gives few clues as to when the auspicious day was said to have happened, and it wasn't until the year 200 that any mention was made of a birthday at all — and then, it was in August. It wasn't until 400 that December 25 even got a mention, and when it comes to Santa, cards, carols, and gifts, they came a lot later... and war had a lot to do with why the holiday didn't just stick around, but grew into the most festive time of the year.

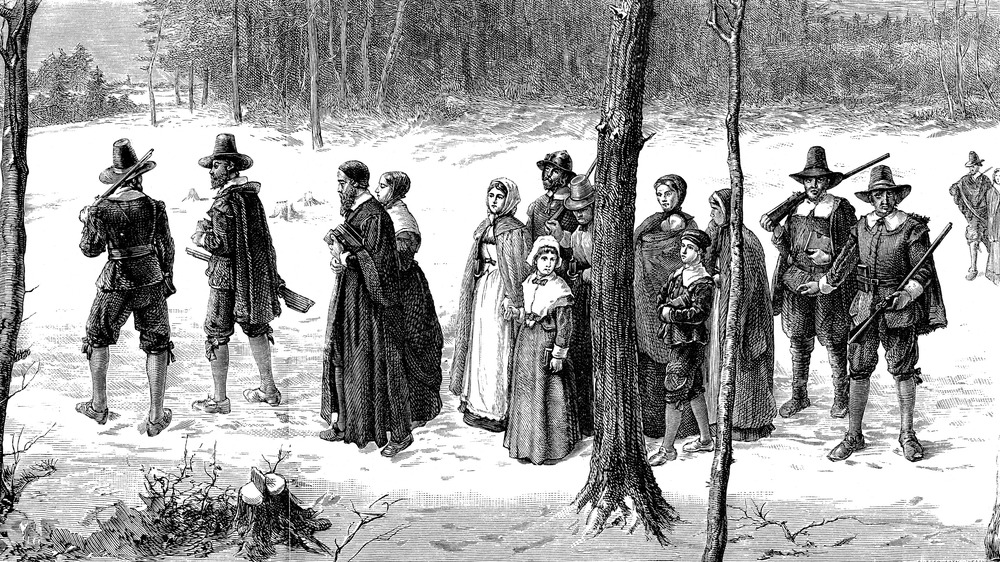

The Puritans that founded the country pretty much hated Christmas

In order to understand how Christmas changed with the American Civil War, it's worth taking a look at what it was like beforehand. Let's start with the Puritans — these early settlers get a lot of credit for laying the groundwork for America, and they were not fans of Christmas. According to Time, they didn't just dislike Christmas, they outright outlawed it. Starting in 1659, anyone caught engaging in a little holiday merriment would find themselves handed a fine, and that was the case until it was made legal in 1681.

Why did Christmas get so much hate? For starters, they didn't call it Christmas: it was called Foolstide, which is actually an excellent name. And there were a few reasons they hated it, starting with the fact that it was popular in England and across Europe... and anything that encouraged some less-than-religious behavior wasn't cool with them. The Puritan minister Cotton Mather argued that "men dishonored the Lord Jesus Christ more in the twelve days of Christmas" than they did throughout the rest of the year, and that's stern stuff. Add in the fact that the Bible didn't really mention Christmas, and the Puritans were having none of those shenanigans.

It stayed that way for a long, long time — in the areas settled by the Puritans (like Massachusetts), schools and businesses kept up the tradition of staying open on Christmas well into the 19th century.

There wasn't much consistency to how Christmas was celebrated

Outside of Puritan America, what Christmas meant depended a lot on who you were, where you came from, and whether or not you were the religious sort. According to VOANews, some people made December 25 a solemn religious holiday, while others went the drinking, hunting, merry-making, and carousing route. For many, it wasn't even on their radar as a holiday, and it was just a regular day.

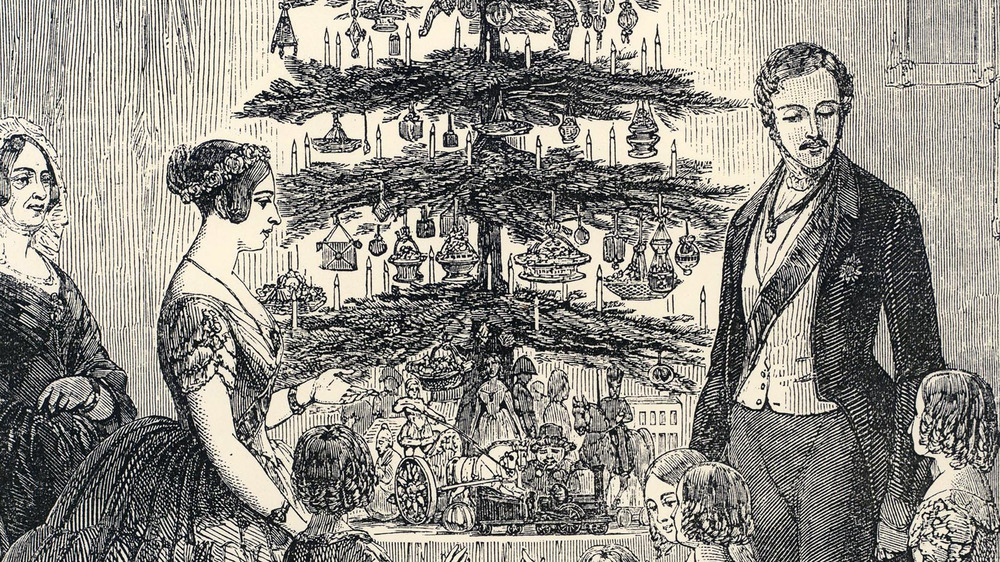

That started to change with a few things. Christmas in England was getting a bit of a boost in popularity thanks to Queen Victoria, who was adopting things like Prince Albert's fondness for decorating Christmas trees. On the American side of the pond, Washington Irving wrote The Sketchbook of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent., and in spite of that un-Christmassy sounding title, it really got people excited about what the holiday could be. It came out in 1819, and it promoted the idea of a peaceful, family-oriented sort of holiday that sounds really good on paper.

Add in an influx of immigrants who were bringing their Christmas traditions with them, and it was suddenly something that many more people were thinking about. By the middle of the 19th century, it was popular enough that some states were making it an official holiday. (Louisiana, for example, took the jump in 1837.) But still, when the Civil War broke out, Christmas still wasn't the same throughout the fractured nation.

Christmas had just been getting started when war broke out

In the decade before the Civil War, familiar Christmas traditions started taking hold. People were more likely to know the words to some of the carols being sung in public squares, and they were really getting the hang of the idea that the long, dark days of December were for some holiday cheer, feasting, and family.

The City of Alexandria says that Christmas of 1860 was, for many, about as far from cheerful as it could get. Civil unrest was widespread, and many were well aware of the fact that violence — if not outright war — was inevitable. One Arkansas diarist recorded this holiday sentiment: "Christmas has come around in the circle of time, ... but there is gloom on the thoughts and countenances of all the better portion of our people."

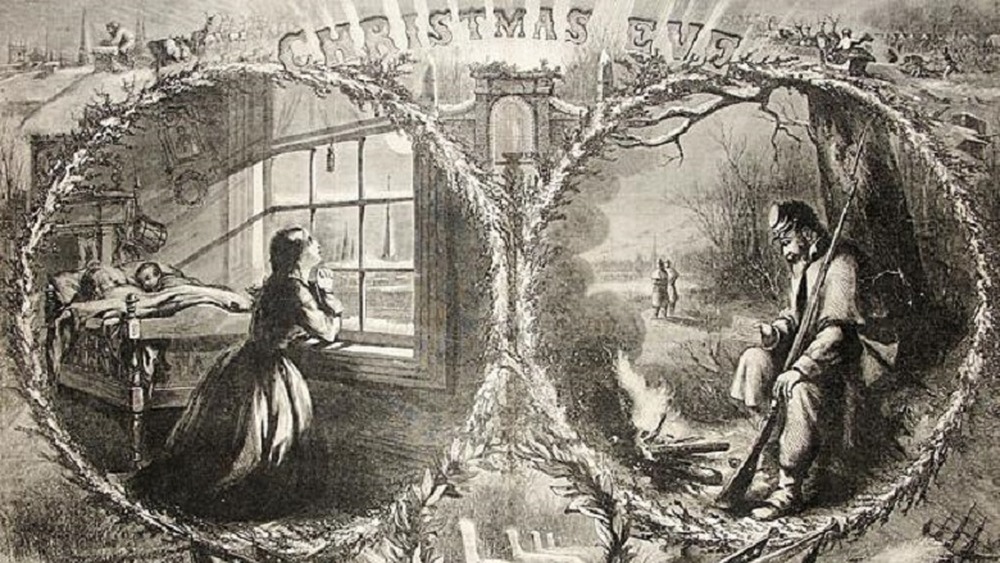

By the following Christmas, the already broken nation was at war. The American Battlefield Trust says that military camps were filled with soldiers who wanted nothing more than to be at home with their loved ones, and that made the pain of conflict a powerful thing. They decorated their tents, traded gifts with each other, and wrote heartbreaking letters to their families. Families responded with sentiments like this one from Sallie Brock Putnam of Richmond, Virginia: "Never before had so sad a Christmas dawned upon us... We had neither the heart nor inclination to make the week merry with joyousness when such a sad calamity hovered over us."

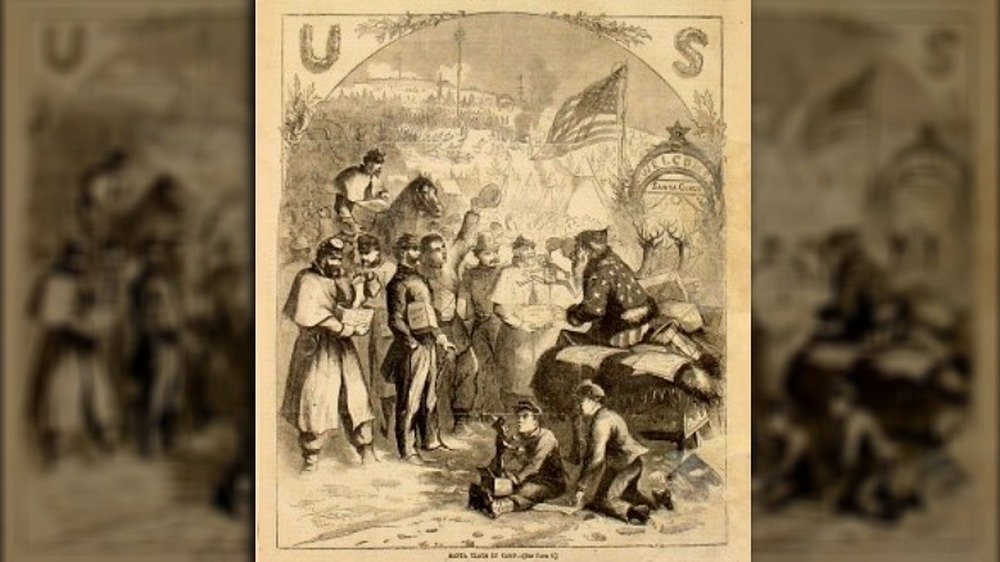

Santa Claus became the character we know him as today

During the Civil War, the magazine Harper's Weekly had a widely popular illustrator named Thomas Nast. Nast was known for running political cartoons, and when the Civil War happened, he was clearly on the side of the North. When Christmastime rolled around, he took the opportunity to create a character that could give Christmas to the North — and the abolitionists — once and for all.

In January of 1863, Nast ran two Christmas-themed illustrations that featured a bearded, jolly, gift-giving figure that would look familiar to all 21st-century Christmas lovers. It was, of course, Santa Claus, and Nast had taken his inspiration from a few places, including Clement Clarke Moore's A Visit from St. Nicholas, which many people know better as 'Twas the Night Before Christmas. Also incorporated into Santa was Nast himself: the Smithsonian says he used his own rather round, bearded self to make Mr. Claus something of a self-portrait. In his earliest cartoons, Santa brought gifts to the soldiers on the front lines of the Civil War, and snuck down the chimneys of families who missed their loved ones.

Nast continued his holiday illustrations featuring everyone's favorite gift-giving elf, and by 1886, he had done 33 panels in which Santa promoted whatever political ideology Nast supported at the time — which included things like abolition, higher pay for the military, and equal rights. While those political ideas have largely been forgotten, Santa and Christmas have become inseparable.

Christmas trees really caught on

The idea of the Christmas tree goes back much farther than the Civil War: according to Culture Trip, German immigrants brought the practice to the US in the mid-1700s and Queen Victoria helped popularize it, but HistoryNet says that it was 19th century illustrators like Thomas Nast and Winslow Homer who really helped raise the profile of the now-popular Christmas tree. Their illustrations were incredibly popular, and it's no wonder that people who saw them started including them in their Christmas traditions. But Civil War-era contributions to our favorite evergreens were about more than just the trees themselves.

Shelley Cathcart, assistant curator of the Old Sturbridge Village in Massachusetts, says (via Curbed) that the earliest Christmas trees were decorated with things like ribbons and candles. Swansea University history professor David Anderson adds (via The Conversation) that by the time Civil War soldiers were decorating the little trees they put up in their tents, they couldn't get the fruit and cakes they were used to, so they used things like pork and hardtack.

Once the war was over, a whole new industry popped up. It was built around the Christmas bauble, and as early as the 1870s, stores were encouraging people to buy their Christmas decorations rather than relying on the handmade ones they'd used during the war. The bauble industry became highly commercialized, and by the 1890s, selling imported Christmas tree ornaments had become a multi-million dollar industry.

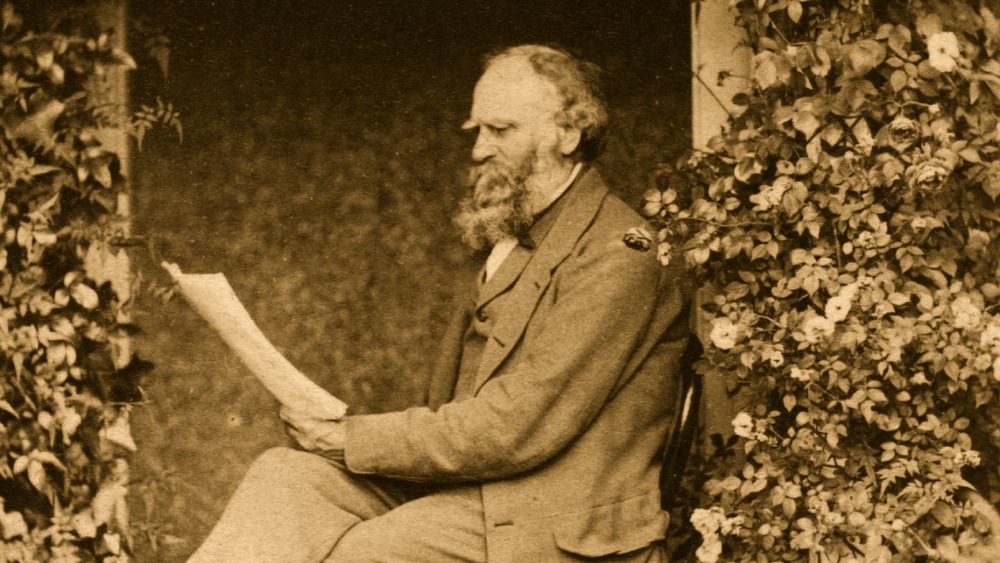

I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day

There's a ton of Christmas carols out there, and one of the most famous — "I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day" — wouldn't have happened without the Civil War. The story is incredibly sad, and it starts with Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. According to the American Battlefield Trust, Longfellow's son, Charles, had run away from home to enlist in the army. Then, on December 1, 1863, the elder Longfellow got a telegram telling him that his son had been badly wounded a few days earlier. He had been shot, and the bullet had hit his spine. Needless to say, things didn't look good, and he headed out. It was five days before he and his son met in Washington, D.C., and different doctors gave different opinions, from suggesting paralysis might be permanent, to reassuring them that he'd be back in the field in six months.

Longfellow wrote the poem Christmas Bells about the incident, and it was dark stuff. He wrote, "And in despair I bowed my head; 'There is no peace on earth,' I said; 'For hate is strong, and mocks the song, Of peace on earth, good-will to men!"

The poem was later set to music, and was first sung in 1872. Since then, it's been covered by people like Elvis and Bing Crosby, making this poem — written by a worried father — an iconic Christmas tune. As for Charles, he recovered, although his military career was at an end.

Gifts for the military

Anyone who has ever taken the time to send Christmas gifts to military personnel deployed overseas for the holidays should know that they're participating in a time-honored tradition observed during the Civil War. Swansea University professor of American History David Anderson says (via The Conversation) that instead of just sitting around worrying about their absent loved ones, many women— from the North and South — spent the Christmas seasons doing what they could for not just their husbands, brothers, and sons, but for all the soldiers. Many spent their time volunteering at local hospitals, and still more turned their attention to making clothing or preparing holiday gift boxes to send to the soldiers in the field.

They weren't the only ones thinking of the men so far from home, either. According to President Lincoln's Cottage, President Abraham Lincoln, wife Mary, and son Tad spent Christmases during the Civil War visiting wounded soldiers in Washington, DC. hospitals. After those visits, it was Tad Lincoln who decided that the wounded men deserved a Christmas, too, and — with help from his father — sent them gifts. Most received things like books and clothing, along with a tag signed by the littlest Lincoln.

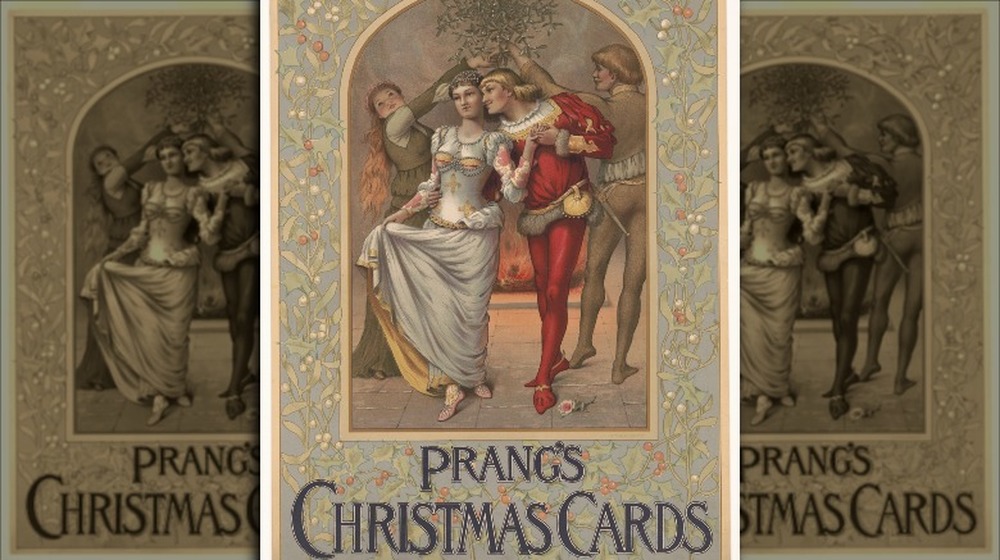

The popularity of Christmas cards

While it was England's Sir Henry Cole that first came up with the idea of the Christmas card, it was Louis Prang who's considered the father of the American Christmas card. Prang was born in what's now Poland in 1824, and in 1850, he settled in Boston. According to Civil War Profiles, by the time war broke out he was already running a decently large business with seven printing presses, and when it came time to deliver what the people wanted, he avoided the typical battle-scene lithographs that were all the rage. Instead, he printed thousands of affordable maps, some of which came with colored pencils so buyers could trace the movements of armies. He was massively successful.

According to the New York Historical Society, Prang learned a new process of printing in 1864 — which allowed printing in color — and he changed the industry. Post-war, he turned his printing presses to printing Christmas cards designed, notes the New England Historical Society, entirely by women.

Prang wrote, "My object in starting the project has been principally to give an impetus to female art." By 1881, Prang had hired more than 100 women to design the cards from start to finish, and by that same year, he was printing around five million cards each Christmas. He was ultimately pushed out of business by printers making cheaper cards, but there's no denying that he's the reason many still feel a commitment to send those holiday cards.

War changes people's perceptions of what's really important

Historian Penne Restad says (via History Today) that one of the things that the Civil War did for Christmas was to increase the appeal of a holiday dedicated to the celebration of what's really important: friends and family.

Restad describes America's modern Christmas as "a response to social and personal needs that arose at a particular point in history," and specifically, in response to the division and loss suffered by families across the country and on both sides of the divide. Restad continues that the cementing of Christmastime traditions around the time of the Civil War "helped the nation to make sense of the confusions of the era and to secure, if only for a short while each year, a soothing feeling of unity."

And there was a lot to overcome in those years. According to The New York Times, it's long been known that the American Civil War was the deadliest conflict the US has ever been involved in, and research published by Binghamton University historian J. David Hacker in 2012 estimated the death toll at around 750,000. It's no wonder that more and more people began to look at Christmastime as a time to spend with their loved ones.

Things were changing during the Civil War — super fast

While it seems like the Civil War might be something all-encompassing, it wasn't the only thing going on in the mid-19th century. Historian Penne Restad says (via History Today) that there was something else at work here that helped make Christmas popular, and it was change.

Restad argues that the population of the country was changing, immigration was introducing new ideas about what it meant to be "American," and at the same time, the age-old way of life was being replaced with something much more focused on urban centers and industrialization. Life was getting much more fast-paced, and that was all coming together to make people yearn for the way things had been in the good old days, before the war. They wanted their family — their entire family — gathered around the hearth, sharing a meal and telling their stories.

Restad puts it this way: "At the crossroads of progress and nostalgia, Americans found in Christmas a holiday that ministered to their needs. The many Christmases celebrated across the land began to resolve into a more singular and widely celebrated home holiday."

And in the 21st century, nostalgia remains a huge part of Christmas: it's why we watch the same movies and listen to the same songs we have for decades, and smile while doing it.

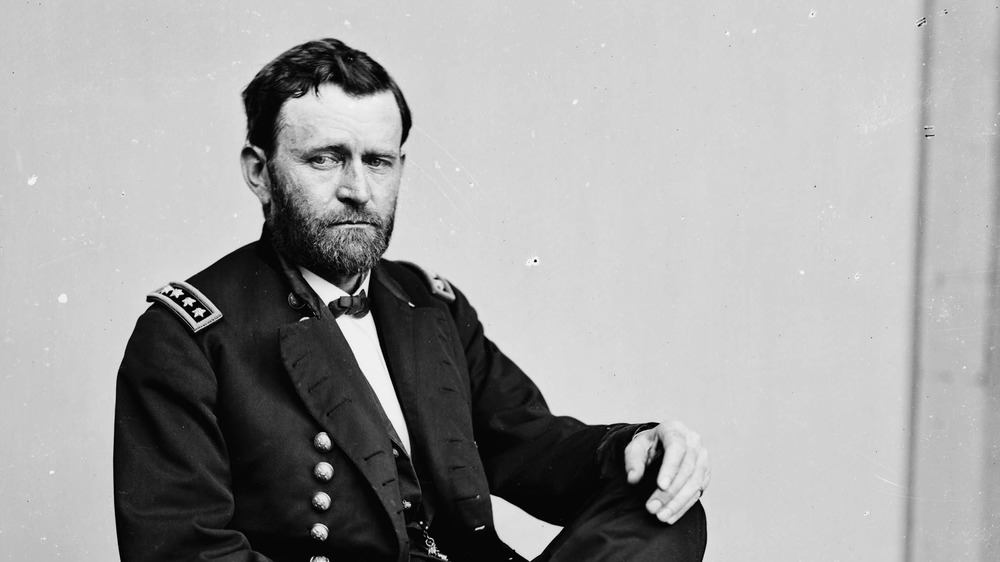

Christmas wasn't declared a federal holiday until 1870

When it came to making Christmas an official holiday, some of the states did it long before the Civil War. Alabama actually led the way, becoming the first state to make the holiday official in 1836.

But as far as Christmas on a nationwide scale, December 25 didn't become Christmas as we know it until June 28, 1870. That, says Time, is when President Ulysses S. Grant signed a bill that made it a legal holiday. (And according to congressional records, there was no opposition to making a religious holiday into a federally recognized one: they were simply giving people a day off that just happened to be on a day significant for some religions.)

It's not a coincidence that the declaration of Christmas as an official US holiday came so close to the end of the Civil War. University of Texas at Austin lecturer Penne Restad says that although the desire for a holiday that would reunite the North and the South after a period of war might have been part of it, it was a combination of factors: publishing houses helped spread the customs of one group to another, and in the face of war, upheaval, loss, and change, the establishment of Christmas helped people across the country in defining just what it meant to be American... which everyone was, once again: North and South.