The Crazy Real-Life Story Of The Man Who Created Santa Claus

When it comes to Christmas, there's a lot of imagery that just screams holiday cheer (loudly, repeatedly, and for many more months than is really necessary). There's Christmas trees and decorations, holly and mistletoe, snowmen and reindeer, and the biggest one of all — Santa Claus.

There's a good chance you've heard the rumor that Coca-Cola invented our modern image of Santa. Listen to them tell the story, and they'll say that it was their illustrator Haddon Sundblom who, in 1931, "established" Santa with his jolly countenance, red suit, white beard, and ho-ho-ho habit.

Read between the lines, though, and you'll notice that they're careful not to say they actually created Santa — because they absolutely, definitely did not.

Santa as he is known today first appeared way back in 1863 — a year which, Smithsonian notes, was notable for the fact that the American Civil War was in full swing. It's no coincidence that Santa appeared to spread a little holiday cheer, and the man who actually did create the jolly old elf that is known and loved today had a fascinating — and occasionally dark — story.

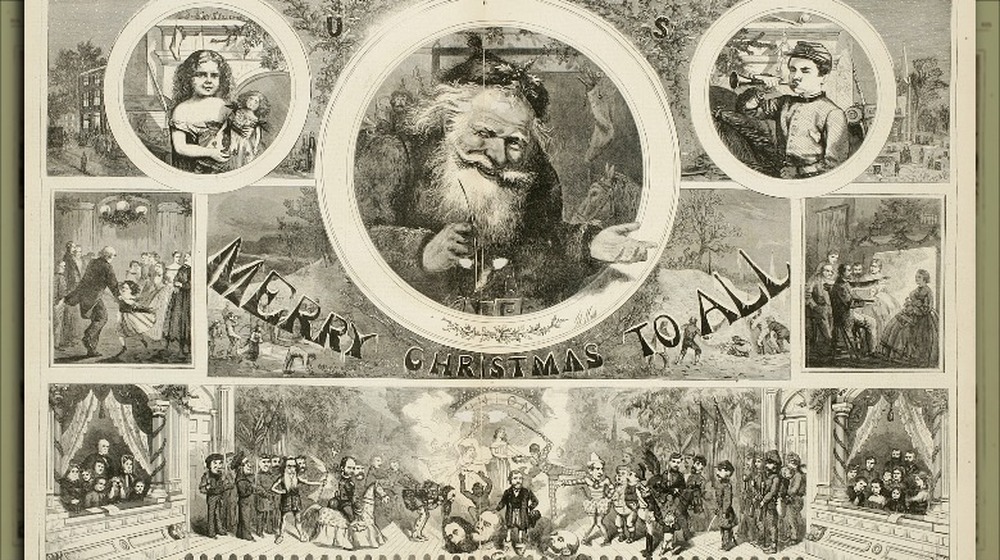

The cartoons that created our modern-day Santa

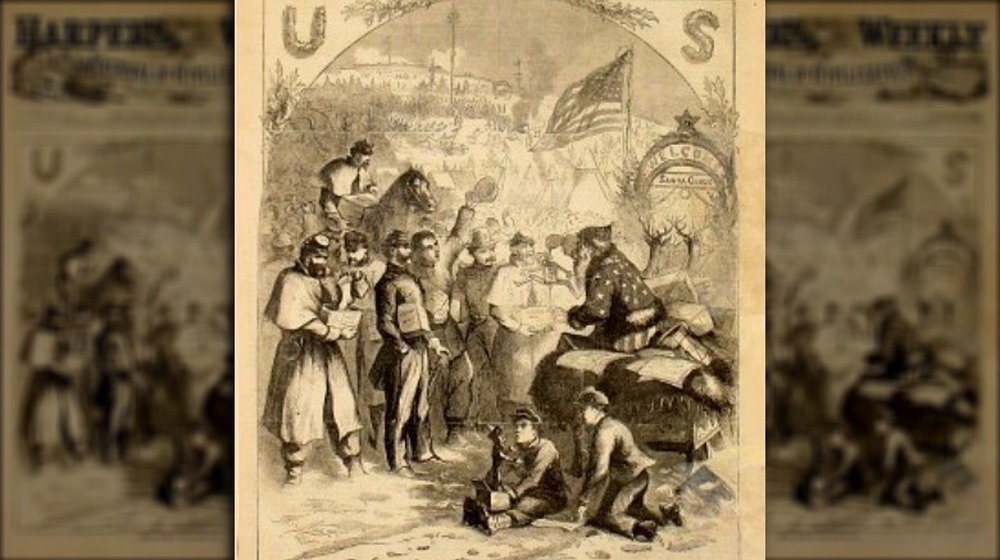

During the 19th century, Christmas really made a jump from a somber religious holiday to the gift-and-merriment fest more familiar to 21st-century eyes. Santa's a huge part of that, and according to the Smithsonian, the Santa Claus in his jolly old elf form first showed up in a pair of Harper's Weekly cartoons that — strangely — ran after Christmas, in January of 1863.

In one (pictured), a bearded Santa clad in stars and stripes is handing out toys to Union soldiers — including a doll in the likeness of Confederate president Jefferson Davis, dangling from a rope around its neck. The other features two separate drawings — on one side, a woman looks forlornly out the window, and on the other side, a soldier sits staring into a fire. The background is part Christmas Eve — complete with Santa getting ready to hop down a chimney — and part cemetery.

It was powerful stuff that drove home just how many people were separated by war — and death — during that Christmas season, and it was the work of a Bavarian immigrant named Thomas Nast. Between 1863 and 1886, Nast would create 33 Christmas illustrations featuring a Santa that was a bit of a self-portrait (and based on works like A Visit from St. Nicholas or 'Twas the night before Christmas). During the war, he used Santa to illustrate his beliefs in civil rights and the abolition of slavery, and afterwards, Santa got on board with other causes.

The propaganda of Santa

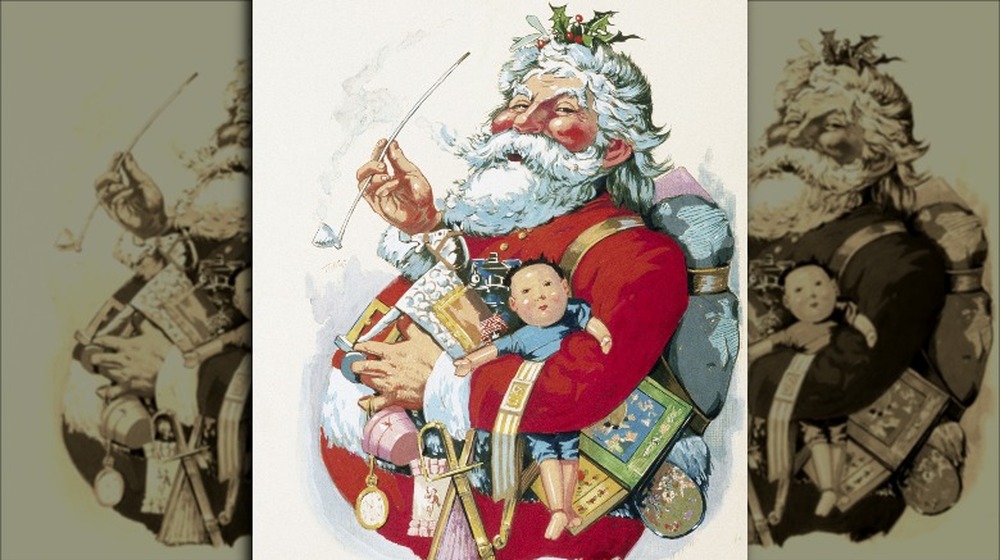

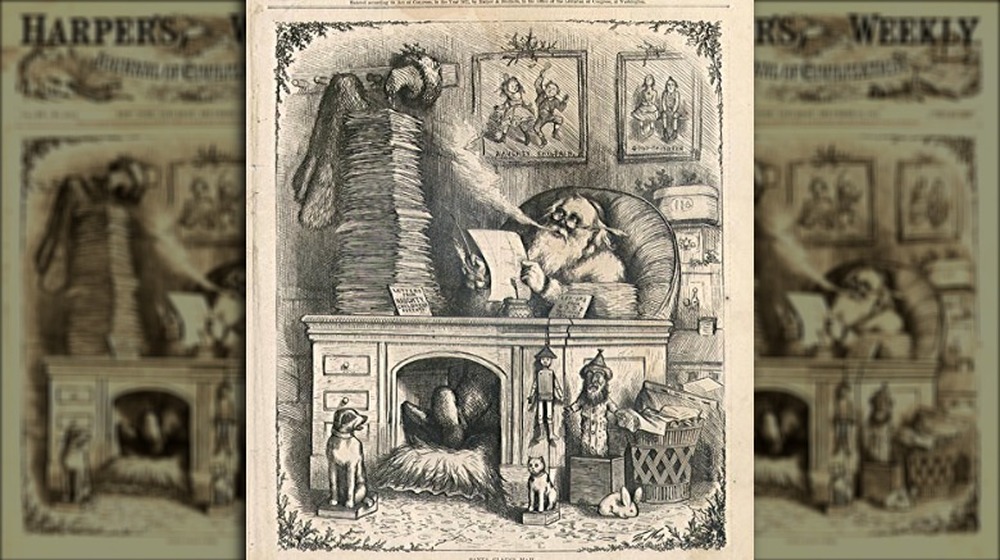

There's one illustration in particular that pretty much cemented Santa's image as a jolly, rather round chap sporting a big white beard and with a preference for wearing red (that's pictured here). But here's the thing — it's not just a guy that's breaking into homes and dropping off toys. Thomas Nast used Santa to push a lot of propaganda — just take another look.

He's not carrying a sack of toys. That's a soldier's backpack he's got — along with other military imagery like a dress sword and an Army belt buckle. He's also carrying a horse and a pocket watch that could be considered toys... so what gives?

Ryan Hyman of the Macculloch Hall Historical Museum says (via the Smithsonian) that Nast and his colleagues had realized the popularity of Santa and their Christmas images were a chance to spread wider awareness — and in this particular case, he was appealing for fair wages for soldiers. The horse is meant to represent the Trojan horse and treachery (this time of the United States government), and the time on the watch — ten minutes to midnight — signified the pressing need to make a decision to pay members of the military more.

Santa might not be as loaded with propaganda today, but when Nast first created him, he was a vehicle that advocated for civil rights and social change.

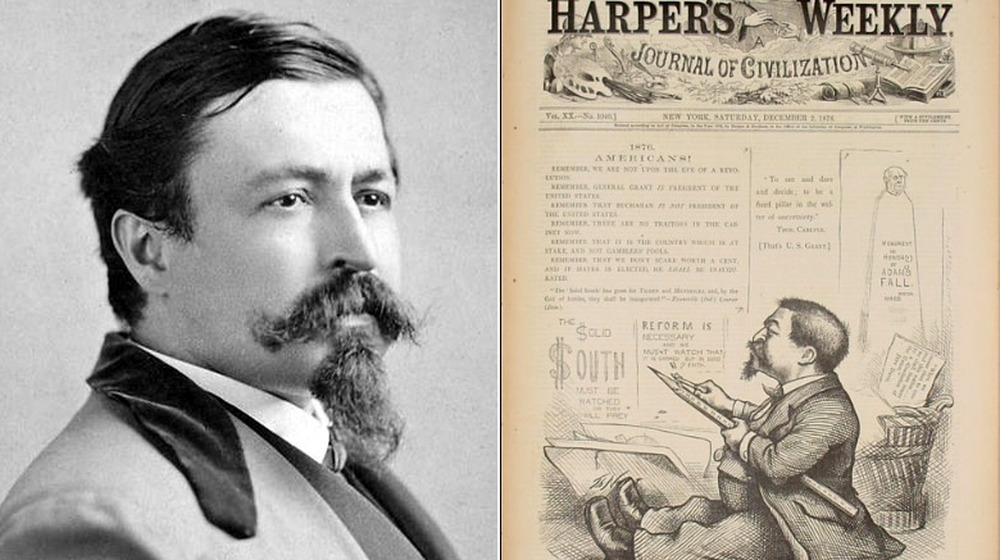

Drawing was Thomas Nast's life from childhood

So, who was the man wielding the pen that drew Santa?

Thomas Nast was an immigrant. He had been born in Landau, Bavaria, in 1840. According to his grandson, Thomas Nast St. Hill (via American Heritage), Nast's father had ideas liberal enough that the whole family thought it best they seek their fortunes elsewhere. It was 1846, and the Nast family patriarch finished his enlistment in the Bavarian 9th Regiment Band then followed a few years after his wife, son, and daughter. When he did, he found work in an orchestra and finally in the Philharmonic Society.

As for the then 6-year-old Nast, his schooling was hampered by the fact that he couldn't speak any English. He could draw, though. He had enough promise that his parents transferred him to art school but ultimately weren't able to pay his tuition. At 15, Nast's formal education was over, and he needed to find his own way in the world. So he did what any ambitious 15-year-old would do — he walked into Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper and asked for a job.

Leslie told the kid to head down to a Manhattan ferry during rush hour and draw a picture of the crowded boat, so that's what Nast did. Leslie was so impressed with what he brought back that he hired him on the spot. It ended up being fortuitous, as his salary allowed him to help support his family after the death of his father in 1858.

Thomas Nast and the Civil War

In 1860, states started seceding from the U.S., and it wasn't long before the conflict escalated into a full-scale war. Thomas Nast joined Harper's Weekly not long after — in 1862 — and according to the Massachusetts Historical Society, it wasn't long before he became known for his wartime illustrations. At the same time he drew scenes that unconditionally supported the Union and cheered them on their way to victory, he also drew some of the most sentimental, touching scenes of what it was really like for soldiers on the front lines.

Good propaganda is important in any political cause, and it's impossible to stress just how popular Nast and his illustrations became. According to Gen. Ulysses S. Grant (via the Smithsonian), Nast "did as much as any one man to preserve the Union and bring the war to an end."

Santa Claus was just part of that. Nast's depiction of Santa brought home the loneliness of war, the sadness of soldiers on the front, and the worry and heartache suffered by those at home. Harper's Weekly had circulation numbers of more than 100,000 (via George Washington University), and that's a lot of people seeing his message. Even President Abraham Lincoln was said to have commented on the importance of his heralding of emancipation, quoted as calling Nast "our best recruiting sergeant," adding, "This emblematic cartoons have never failed to arouse enthusiasm and patriotism, and have always seemed to come just when these articles were getting scarce."

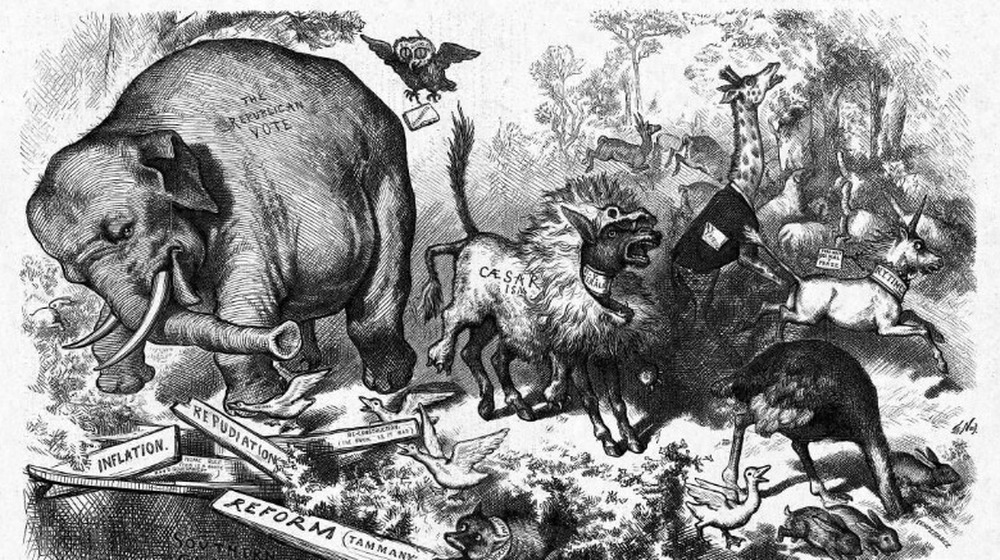

The donkey and the elephant

Even those who don't follow politics are familiar with the Democratic donkey and the Republican elephant, and that's also the work of Thomas Nast.

First, it's worth noting that contrary to popular belief, Nast didn't actually create the Democratic donkey. The Smithsonian says that particular symbol was created by the opponents of 1828 presidential candidate Andrew Jackson, who likened his stubbornness to a donkey. It was used briefly in the 1830s and was then forgotten — until Nast's 1870 cartoon depicting a donkey kicking a dead lion (representing the Democratic party and then-deceased Lincoln press secretary E.M. Stanton), which undeniably linked the animal to the political party.

The elephant is less clear, and it was Nast that came up with that particular association. It's believed he chose an elephant for the Republican party as a reference to the Civil War and the Union's victory... but it's not 100 percent for sure. In 1874, a cartoon (pictured) depicting a donkey wearing a lion's skin chasing an elephant into a pit brought up another suggestion — he may have chosen it because it was big, powerful, easily frightened... and dangerous when running scared. Whatever the reason, Nast's illustrations are the reason the two symbols have endured for decades.

Thomas Nast popularized Uncle Sam

Thomas Nast was behind another enduring symbol of the U.S., too — Uncle Sam. According to History, Uncle Sam was a real person. His name was Samuel Wilson, and he was a New York meat packer who supplied the Army with valuable rations through the War of 1812. The barrels he shipped meat in were stamped "U.S.," which soldiers began calling "Uncle Sam's."

Newspapers took the reference and ran with it, and it wasn't long before Uncle Sam became synonymous with the United States. But, it wasn't until Nast started drawing a personification of Uncle Sam that he started to take on a personality of his own.

In 1869, Nast drew an illustration called Uncle Sam's Thanksgiving Dinner, and The Atlantic says that it was basically illustrating an idea that Abraham Lincoln championed — it wasn't blood, nationality, or ethnicity that made someone American, it was the sharing of common ideals and convictions. Nast's illustration shows a diverse group sitting around a Thanksgiving Day table while Uncle Sam carves the turkey, and it includes the captions "Come one, come all" and "Free and equal." The message was clear — Americans are Americans, no matter what they look like.

Gradually, Nast's Uncle Sam evolved to sport the white beard and the stars-and-stripes wardrobe known today. (Although it is worth noting that the most famous depiction of him — the recruitment poster — wasn't Nast, but another artist named James Montgomery Flagg.)

Thomas Nast really had a problem with one particular group

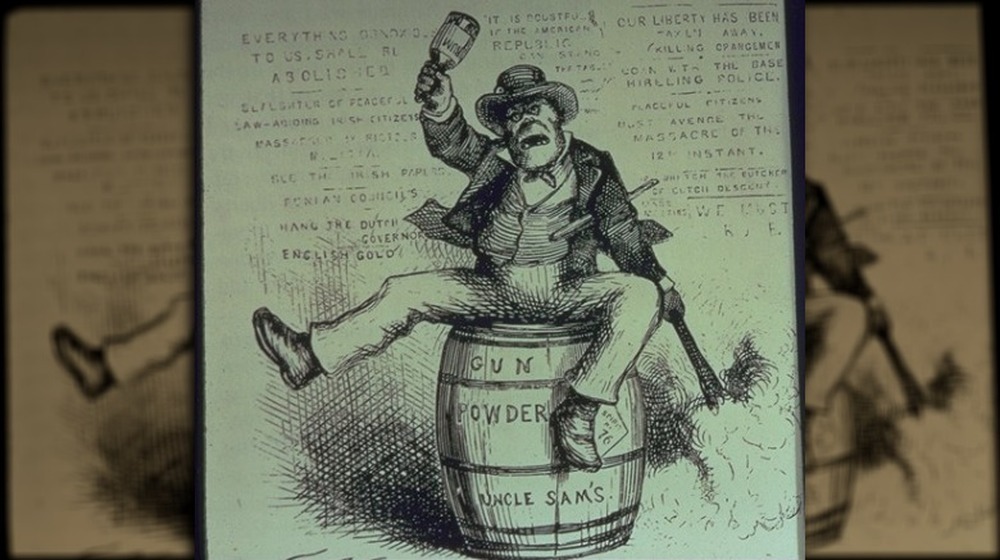

When it comes to racial stereotypes, there was one 19th century group The Washington Post says were "associated with poverty, drunkenness, crime, and [...] one more thing: terrorism." What was this group? The Irish.

What was going on at the time was complicated, and Thomas Nast used his political clout to not only popularize the image of Irish immigrants as sub-human ape-man — like the one portrayed in his illustration "The Usual Irish Way of Doing Things." That particular piece (pictured) shows an ape in human clothing (via City University of New York).

According to NJ, Nast's hate of the Irish came because they were one of the main supporters of Tammany Hall, the ultra-corrupt bastion of the Democratic political party that ran New York City at the time. While they stress that Nast targeted the Irish seemingly for that reason alone (and would have done the same for any ethnic group in that position), Thomas Nast Cartoons points out that he was also hopping on — and promoting — stereotypes already rampant in an overwhelmingly anti-Irish society that was started (in part) by British colonizers who felt they needed to justify their occupation of Ireland.

Nast, they add, went one step further — he was a firm believer in "racial-biological differences" that laid the groundwork for eugenics. He was one of many who had his skull measured and documented as proof of his native, race-based intelligence.

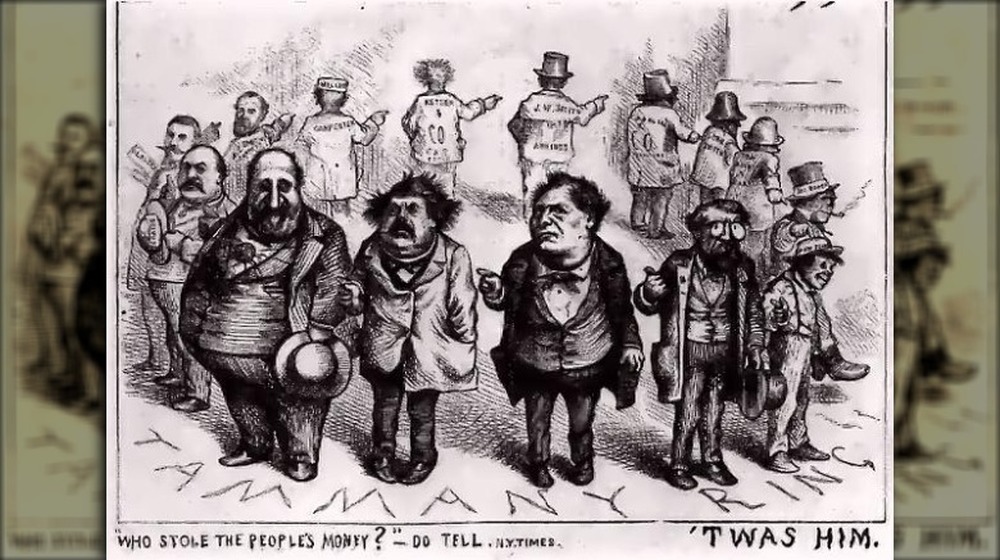

Thomas Nast vs. Tammany Hall

One of Thomas Nast's biggest targets was the corruption of Tammany Hall, New York City's stronghold of the Democratic party. It was led by William "Boss" Tweed, and just to give an idea of how corrupt an organization this was, let's look at the building of the Municipal Courthouse. Tweed was in charge of funds, and his kickbacks meant the courthouse ended up costing the state $13 million. Put another way, the original budget was $300,000, but Tweed's oversight meant the state was charged $350,000 on carpet alone (via The New York Times).

Nast, says George Washington University, kicked off a campaign to bring the corruption of Tweed and Tammany Hall to light. In 1871, he was offered a bribe to go away to Europe, which he turned down — but he did move his family to New Jersey when it escalated into a matter of personal safety.

Tweed and his immediate group of cronies were dubbed the Tweed Ring and made a habit of grossly overcharging the state for construction projects. They were also known for naturalizing immigrants in exchange for their votes and using their political influence to put an end to court cases.

Ultimately, it was Nast's cartoons that were credited with turning the public against Tweed and his cronies, and Tweed was arrested (but miraculously, still kept his seat in the senate). What followed was a dramatic run from the law, which finally ended when he was arrested in Spain — where he was identified based on one of Nast's illustrations.

Living the good life

Thomas Nast's crusade against Boss Tweed had been pretty successful. Tweed's cronies saw justice, and Tweed himself died in 1878 as a prisoner at the city's Ludlow Street Jail. As for Nast, the popularity he'd enjoyed during the Civil War only escalated, and he was known nationwide for his crusading sense of justice as well as for the figures he'd made famous.

Life was pretty good for Nast. According to grandson Thomas Nast St. Hill (via American Heritage), he was fairly wealthy by this point. He'd also made a lot of powerful friends. When Ulysses S. Grant was elected president, he credited in part "the pencil of Thomas Nast," and that's quite the shout-out.

Among his list of friends was Mark Twain, and it was Twain who regularly tried to convince Nast to go on the lecture circuit with him. Nast got tons of offers but rarely accepted due — mostly — to a paralyzing fear of public speaking. He had little interest in leaving his corner of the world and his family, so even when Twain pitched the idea of touring together — he would speak, and Nast would document the tour in illustration form — he declined, even though Twain estimated they'd net a profit of around $75,000 for the tour. (And adjusted for inflation, that's around $1.8 million in today's money.)

But not for long

Thomas Nast continued to work after the fall of the Tweed Ring, but things took a bit of a turn. According to the Massachusetts Historical Society, much of Nast's work for Harper's Weekly had been done under publisher Fletcher Harper — and Harper gave Nast the freedom to pretty much do whatever he wanted to. Over the course of his career, that had included things like promoting the idea that newly freed slaves should be given the same civil rights as any other American, along with things like women's suffrage and rights for groups like the Chinese immigrants who were settling in the west.

Things changed after Harper's death, and along with a shift in management, the industry was also seeing a change in printing methods. New methods didn't work as well with Nast's distinctive style, and coupled with new management's desire to become less radical, Nast found himself — at just 39 years old — less frequently called upon.

Nast's grandson, Thomas Nast St. Hill, says (via American Heritage) that he took the opportunity to travel and do some investing. Tragedy followed. The silver mine he invested in fell through, and when he made another investment in a Wall Street firm that ultimately failed, he lost all he'd risked.

Thomas Nast had an unlikely end

Thomas Nast had severed his relationship with Harper's Weekly in 1886, and the series of financial missteps he'd made and misfortunes he'd suffered had left him in a dire position. In 1902, salvation seemed to come in the form of a job offer from then-President Theodore Roosevelt.

The offer, says George Washington University, was a far cry from his career as an illustrator. Roosevelt offered him the position as American consul, and he would be stationed in Guayaquil, Ecuador.

Nast accepted the position and headed to Ecuador. His appointment there was short-lived. When he arrived in July of 1902, the country was in the midst of an outbreak of yellow fever. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, yellow fever is spread by mosquitoes and results in headaches, fatigue, general exhaustion, aches, and pains for most people, with many recovering within the week. Some develop severe symptoms, including shock, fever, and organ failure.

Nast's symptoms were deadly. Biography says that he died on Dec. 7, 1902, from yellow fever.