Strange Christmas Traditions That Were Considered Normal 100 Years Ago

Christmas is, to many, the most wonderful time of the year, in large part thanks to traditions that have been handed down through generations within a family. Hanging ornaments on your tree that your grandparents once hung, singing the same songs and watching the same movies you watched last year, and eating the traditional dinner with all the fixings are all things that bring comfort to people at the coldest time of the year.

But while Christmas trees, colored lights, and reindeer are nearly universal thanks to the homogenizing influence of popular culture, before mass media spread the images of a commercial Americanized Christmas around the globe, traditions used to be very different. If you were to look back at the 19th and early 20th centuries, you'd see a rather unexpected holiday celebration. While some of these customs are still practiced on a reduced scale today, here are some vintage Christmas traditions that might freak your bean.

Burning yourself with flaming raisins was a common Christmas game

In modern times, games are not really something you associate with Christmas, unless you count "how much pie can I eat?" as a game. Sure, there's gift-swapping games like Secret Santa, and some families might break out the Monopoly board because they didn't fight enough about politics over dinner, but nobody today games as hard as they did in the Victorian era. Parlor games–games played indoors–were all the rage, and the rowdier the better. While raucous and violent games of hide and seek and blind man's buff were hugely popular at the holidays, nothing exemplifies the trend of "dangerous Christmas game" more than Snapdragon.

As Atlas Obscura explains, Snapdragon was a game played by family and friends standing around a table. On that table they would place a shallow bowl that they first filled with some two dozen raisins (or almonds, grapes, or other small treat that would float). Then the bowl was filled with brandy so that the raisins floated on the surface. Then the key part: the brandy was set on fire. Each person around the table would then reach into the bowl, snatch out a flaming raisin, and try to put out the fire by popping it into their mouth and eating it. You know the old saying: it's not Christmas until somebody gets third-degree burns on their tongue.

Wassailing is like caroling, but with skeletons

One Christmas custom still popular today is going caroling, where groups of people go from door to door singing Christmas songs for those weirdos who still open their door for strangers.

This custom, however, derived from the much older tradition of wassailing, which has its roots in the Middle Ages. As Historic UK explains, the word wassail derives from an Anglo-Saxon phrase meaning "be well" and was the traditional term used for toasting someone's health. It then came to refer to a specific drink customary for the season, usually made from cider or ale mixed with spices and sometimes egg whites or honey. "Wassailing," then, was the tradition of groups of people going out during the 12 nights of Christmas, walking from door to door performing Christmas songs or maybe small plays in exchange for food and drink (the "bring us some figgy pudding" verse of "We Wish You a Merry Christmas" is a vestige of this tradition).

Some regions, especially in the British Isles continue the old wassailing traditions to this day, including the Welsh custom of dressing up as a skeleton horse who challenges people to a rap battle where the prize is food and drink. Additionally, some Brits still wassail the orchard, meaning making offerings of toast and cider to the apple trees, singing songs, and making lots of loud noises in hopes of a bountiful harvest.

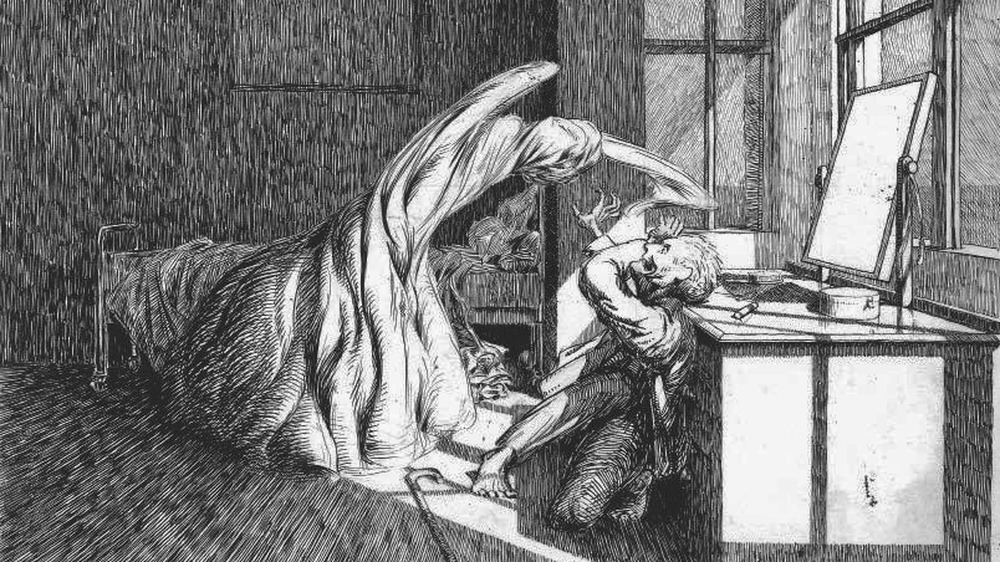

Scary ghost stories and tales of the glories of Christmases long, long ago

To a modern audience, one line in the popular Christmas song "The Most Wonderful Time of the Year" might be confusing: why does the singer say "there'll be scary ghost stories"? That's a weird thing to say about Christmas, a season of tidings of comfort and joy and what-not. Maybe they're thinking of Halloween? And yet, just 100 years ago, such a notion as spooky tales by the Christmas fireside wouldn't have been so strange at all. According to Smithsonian magazine, in the times before electric lights and heat were everywhere, Christmas was notable as one of the darkest and coldest times of the year. Lots of the older, spookier celebrations of Christmas like Krampus come from the danger inherent in the season before modern conveniences. Additionally, before TV, people getting together for a holiday are bound to start entertaining each other with stories. And what's more entertaining than a ghost story?

By the Victorian era, ghost stories for Christmas were a booming industry. You obviously know the most famous Christmas ghost story–there were four ghosts and a grouchy miser? Ring any bells?–but that's not even the only Christmas ghost story by Charles Dickens. Other authors like M. R. James, Algernon Blackwood, and E. F. Benson produced eerie tales for or about the holiday season that are still read (or adapted for TV) in some places–notably the UK–today.

Callithumpian bands were roving Christmas street gangs

Before the establishment of Christmas as a holiday for families and children focused on the opening of gifts on Christmas morning, December used to be a much rowdier time, filled with behavior that would be shocking to most modern Christmas fans. Public drinking, gambling, and excessive eating were paired with aggressive begging and the unabashed invasion of homes by those demanding food and drink. It was a time of upending the established social order; if you've ever heard about the "Lord of Misrule," that's what that was all about. A key example of this boisterous and even dangerous style of Christmas was what were known as callithumpian bands.

As FS explains, callithumpian bands were essentially wandering street gangs disguised as marching bands. They would have traditional instruments, such as horns, whistles, and drums, but they would carry any piece of trash they could make noise with. The trick is, these bands were not actually musically inclined at all, and they were often seeking a bribe–in the form of money, food, or drink–in order to stop playing, in a sort of bizarre inversion of traditional wassailing. One notable callithumpian parade saw a pack of rowdy youths making trouble all across New York, vandalizing taverns and churches, breaking windows, smashing barrels and crates, and physically attacking Black parishioners at a church that just happened to be in their way.

Be careful who you let in your house at New Year's

The Christmas season marks the end of the year, and many older traditions had to do with warding off bad luck and welcoming in good. As a result, symbols of wealth and happiness were (and in some places still are) common in the week between Christmas and New Year's, including four leaf clovers, horseshoes, coins, and fat and happy pigs. Several cultures had (or still have) superstitions about the first person to enter your house being a sign of how your year is going to go. In Scotland, this superstition is still alive and well, where it is known as "first footing."

According to The Scotsman, first footing is a tradition with ancient roots where people try to arrange to have the most fortunate kind of person possible be the first one over their threshold after midnight on the New Year. The best kind of person is a dark haired man bearing symbolic gifts such as bread, coins, salt, coal, and whiskey–representing food, wealth, flavor, warmth, and merriment–while, for example, a doctor would be considered bad luck as it would portend bad health in the house for the year. A minister would hint at a funeral within the year. But the worst kind of person to be the first to darken your doorstep is a redhead or any kind of woman (sorry, ladies).

O Christmas tree, how edible are thy branches

According to History, there is a common legend that Martin Luther was the first to put lights on a Christmas tree, inspired by walking home one winter through the forest and seeing the stars twinkle through the evergreen trees. While it is surely true that Lutherans played a major role in the spread of the popularity of the Christmas tree, this story is probably an apocryphal one. The Encyclopedia Britannica points out that Christmas trees have roots going back not only to times before the Protestant Reformation, but even the Christianization of Europe. Furthermore, the decoration of Christmas trees seems to be tied to a different holiday: the Feast of Adam and Eve, which falls on December 24.

In the Middle Ages, morality plays depicting the story of the Fall of Man in the Garden of Eden included what was called a "Paradise Tree," which was a fir tree hung with apples and other foods. This led to the tradition of hanging various edible goods to a tree in your house on December 24, first including wafers representing the Eucharist, but also fruits and cookies, and over time, the Paradise Tree became a Christmas tree, and the new edible decorations included popcorn strings, candies, and fancy cakes. Glass ornaments became the norm by the 20th century, and nowadays it's pretty rare to decorate your tree with food.

Roasting chestnuts sounds fake, but okay

A song so quintessentially Christmas that its name is literally "The Christmas Song" starts with the iconic opening line, "Chestnuts roasting on an open fire..." Likewise, the lyrics to "Sleigh Ride" talk about listening to chestnuts pop (pop, pop, pop). And yet, where are the chestnuts? When was the last time you roasted a chestnut over any kind of fire, let alone an open one? Roasting chestnuts is not a weird tradition in the way that throwing flaming raisins into your mouth is, it just doesn't happen nearly as much anymore. Why? The answer, in short, is that we killed them.

As USA Today explains, the American chestnut tree was at one point the most common tree in the country, with about four billion trees towering 100 feet high growing from Maine to Alabama. The abundance of chestnuts caused them to be among the most popular ingredients in holiday cooking in the 18th and 19th centuries. However, a variety of Asian chestnut tree that had been imported to Long Island in the early 20th century spread a blight that caused the American chestnut tree to go basically extinct within 40 years. While other countries still have other varieties of chestnuts at Christmas, the American tradition is all but gone. Scientists, however, are working to develop a blight-resistant version of the nut that Nat King Cole sang so sweetly about.

Mail a dead bird to your loved ones

According to History, the first Christmas card was printed in 1843 by English educator Sir Henry Cole, and by the last quarter of the 19th century, postal reforms and advances in printing made Christmas cards an affordable tradition for people all pretty much all levels of society. As a result, by 1870 Christmas cards were a boom business, with hundreds of thousands of cards being mailed annually. As such, card printers had to keep up with demand, and so all sorts of bizarre things got printed on Christmas cards. By modern standards, the Christmas cards of the late 19th and early 20th centuries are often dark, violent, mind-bending, and even spooky.

Sites such as Weird Christmas maintain galleries of these bizarre vintage cards, which include entire series of cards that are just paintings of dead birds for some reason, fairies roasting dead rats, naked babies flying on bats, anthropomorphic Christmas puddings jousting on turkeys, frogs dancing with beetles, and so on, almost always labeled with a generic greeting like "compliments of the season," as if that explained anything. Perhaps the best known of these strange cards today are the Austrio-German Krampus cards, on which Saint Nicholas's demonic companion can be seen punishing naughty children or sometimes flirting with their moms. The homogenization of Christmas since the 1920s has sadly largely put an end to such strange holiday images.

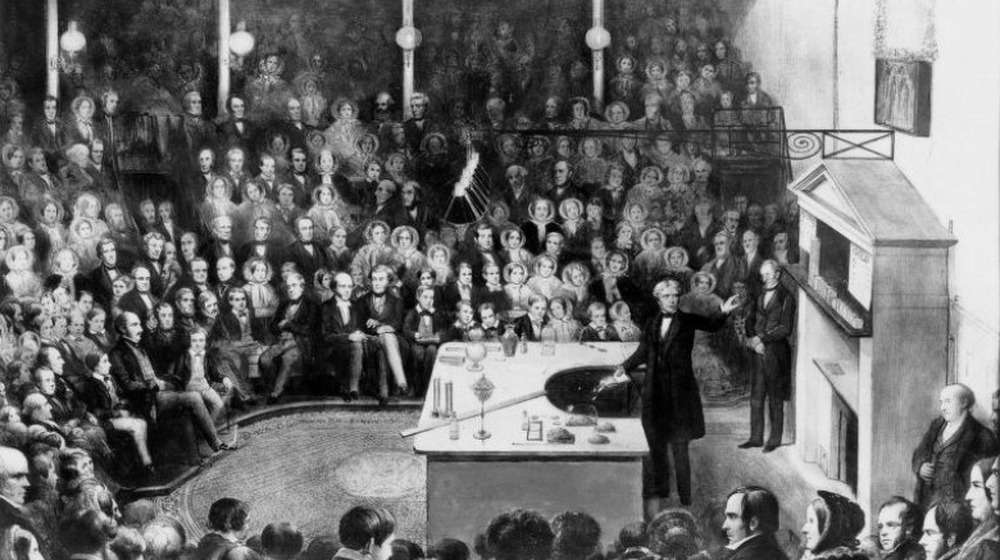

The old science of Christmas

Nowadays, we associate Christmas heavily with magic. Flying reindeer, alive snowmen disobeying cops, and hearts growing three sizes are all commonly recognized examples of the magic of Christmas. However, the Guardian points out that in the 19th century, Christmas was most closely associated with science. There's not any particular reason; there's no story about the Wise Men developing rocket fuel to give to the Baby Jesus or anything. It was really just serendipity: the rebirth of Christmas as a popular celebration thanks to people like Charles Dickens and Queen Victoria's Christmas-loving German husband in the 19th century happened to coincide with science becoming more popular than ever before, leading people to conflate the two things in their minds.

Periodicals began publishing special Christmas issues that featured science experiments and poems praising the forward march of scientific progress, all in a holiday-tinged way. "Scientific Christmas presents" were the rage among Victorian children, and a sensational 1848 Christmas play literally made Science the hero, celebrating the advent of artificial light made possible by fossil fuels. The Christmas season also saw the rise of holiday themed technology extravaganzas held at public exhibitions, galleries, and museums, with Christmas trees decked out with the latest technology. By the advent of the 20th century, however, the common association between science and Christmas had faded, unless you count Zuzu Pets or whatever as Christmas technology.

Feathers are kind of like pine needles, right?

The debate over whether live Christmas trees or artificial ones are better is still going today, with each side ardently defending their preferred position. While Charlie Brown and Linus scorned the popularity at the time of aluminum Christmas trees (more or less single-handedly murdering the aluminum tree industry), these days the most common alternative to a hand-sawn tree is plastic. However, the earliest artificial trees decked their branches with foliage from an unexpected source: birds. As Victoriana explains, the very first artificial trees were made in the 1840s from goose feathers.

Christmas trees were hugely popular in Germany (and soon England and the United States) in the 19th century, but deforestation made Christmas trees scarce for those who wanted them. As a result, fake trees were made out of goose feathers, which were plentiful, with smaller feathers stuck into larger ones to imitate the natural shape of an evergreen tree. The feathers were sometimes painted green to resemble pine needles, but they were often left white. The goose feather tree became popular in the United States in the 1920s thanks to the number of German immigrants bringing their feather trees with them. However, by the 1930s, Christmas tree farms were growing in popularity, and after World War II, Charlie Brown's hated aluminum trees and eventually plastic trees became the preferred way to fake greenery in one's home.

The Yule Log used to be an actual log

Today the Yule Log is still recognized as a Christmas tradition, but these days the phrase usually invokes images of looping video on the television of a fireplace while Christmas carols play in the background. As How Stuff Works explains, this version of the Yule Log began in 1966 thanks to a programming director for a television station in New York who thought the image of a crackling fire on the television might be pleasant for urbanites whose apartments were too small for fireplaces. Or if your family is really fancy (or French), the phrase "Yule log" might conjure up thoughts of the Bûche de Nöel, a Swiss roll-style cake decorated to look like a log with little meringue mushrooms and such.

However, the original Yule Log was just that: a log. As the name implies, the tradition goes back to the pre-Christian northern European winter celebration of Yule. The ritual involved a family going out into the woods to seek out a hardy piece of wood to take back home as their Yule log for the year. They wanted the biggest, thickest piece of wood they could get, because their fortunes as a family were tied to the ability of this log to burn for a long time. For good fortune and as a sign of good will, the Yule Log is supposed to burn continuously for all the 12 days of Christmas. And now it's mostly just a TV thing.

'Twelve Days of Christmas' isn't just a song

To a modern American, the phrase "the 12 days of Christmas" has relatively little meaning. You would definitely recognize the phrase, and you know it has something to do with golden rings and partridges, but to most Americans, Christmas is a holiday that starts after dinner on Thanksgiving and lasts until it's time to return unwanted presents to the department store on December 26. Is that 12 days? Not sure on the math there. When do the 12 days of Christmas start? When are you supposed to bring the pear tree, and when do you need to schedule the drum corps? Is it December 13? Is that the first one?

Well, no. As the Smithsonian Libraries explain, the 12 days of Christmas are the days between Christmas and Epiphany, the celebration on January 6 of the presentation of the Baby Jesus to the Three Wise Men. The evening of January 5 is known as Twelfth Night and has its own traditions, including hiding a bean representing the Baby Jesus in a cake and crowning the person whose slice has the baby in it King for the day (a practice still reflected in New Orleans King Cake traditions). Costume parties with singing, dancing, and charades were once common, as were the presentation of comical and even farcical plays, including one you may have heard of: William Shakespeare's Twelfth Night.