The Crazy, Real-Life Story Of Simon Wiesenthal, Nazi Hunter

The Simon Wiesenthal Center describes itself as "a Jewish global human rights organization researching the Holocaust and hate in a historic and contemporary context." They have locations around the world, and they're also behind the Museum of Tolerance, the educational branch that teaches visitors about the consequences of racism — and what they can do to increase our capacity for tolerance, and prevent hate crimes before they happen.

The center's namesake was a very real person, and to say he went through a lot... that's an understatement. After Simon Wiesenthal was liberated from the Mauthausen concentration camp in 1945, he made it his mission in life to not only see escaped Nazis brought to justice, but to talk to other survivors and get them to tell their stories in hopes of preserving the horrors of what had happened in Nazi Germany, and to help prevent it from happening again.

His life story is one of incredible hardship and unimaginable loss, all culminating in a legacy that's leaving a lasting impact. Wiesenthal once wrote, "The history of man is the history of crimes, and history can repeat. So information is a defense. Through this we can build, we must build, a defense against repetition." And so, he did.

Simon Wiesenthal's lifetime of persecution

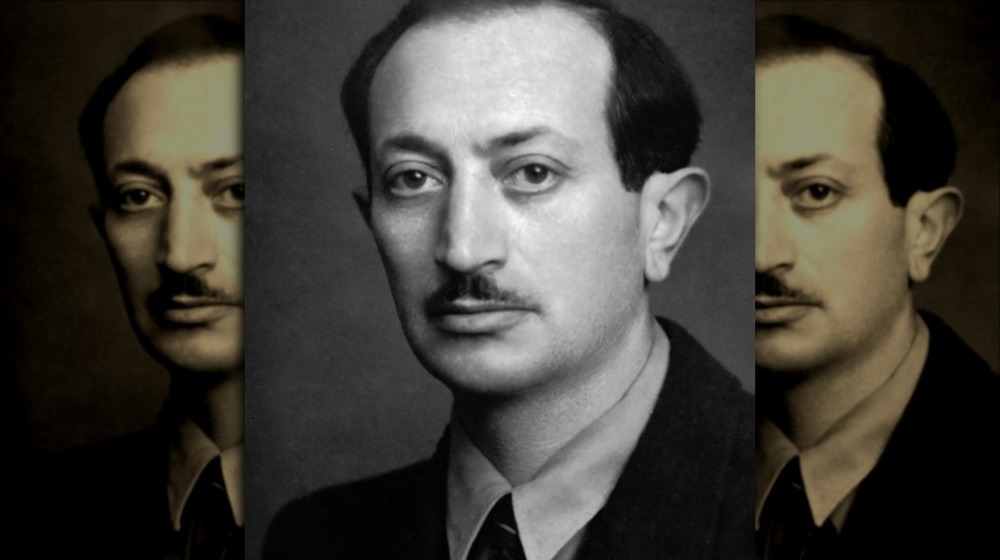

Simon Wiesenthal's experiences with the darker side of human behavior go back before WWII. He was born on Dec. 31, 1908, in an area of the world once called Buczacz, that the Simon Wiesenthal Center says is now part of Ukraine. In 1915, the Cossacks — military units under the control of Russia and the Soviet Union (via Britannica) — invaded his homeland, which was already hotly contested and often volatile. Wiesenthal, his mother, and his brother fled to Vienna as refugees. They had already lost his father: the army reservist had been killed at the outbreak of World War I.

According to The Guardian, they were able to return home by 1917, but it wasn't a peaceful place. After Russia's withdrawal, the area fell into the hands of first the Ukrainians, then the Polish, and then — in 1920 — it became a territory controlled by the Soviet Union. Even that wasn't going to last: after Hitler ordered his troops to march across Poland, the Soviet were driven out by the Wehrmacht.

Through it all, Wiesenthal continued to study. He had a natural gift, and it became clear very early on he was a natural draftsman, and he wanted to go to school to become an architect. Even then, he felt the stigma of his Jewish faith: he was unable to attend school in Lvov (now Lviv), so he headed to the Czech Technical University in Prague.

On the cusp of war

Simon Wiesenthal got his degree in 1932, and by 1936, he had married Cyla Mueller (pictured together) and settled down to work in an architectural firm in Lvov. The quiet life was short lived: in 1939, Russia and Germany signed a nonaggression agreement, divided up territories, and it wasn't long before the Russian army swept through Lvov. According to the Simon Wiesenthal Center, that's when Lvov's Jews started feeling the pressure. Business owners were forced to close up shop, and faced even worse than an end to their livelihood. Wiesenthal's stepfather was arrested by the People's Commissariat of Internal Affairs (NKVD), and died in prison. His brother was shot, and Wiesenthal, pressured into closing his business, suddenly found himself needing to find another way to make a living.

He became a mechanic, working in a factory that made bedsprings.

It wasn't long before he and his family found themselves facing deportation into the farthest, most desolate reaches of the north: Siberia. According to the International Business Times, it was 1940 when Stalin ordered between 200,000 and 300,000 Jews to be moved from Russian-occupied territories to remote labor camps. Countless people died there, and Wiesenthal, his mother, and his wife only escaped that fate by bribing a NKVD commissar. By 1941, German troops had replaced Russian ones, and at first, he was able to avoid being targeted by the Nazis thanks to contacts within the Ukrainian Auxiliary police. That didn't last.

Simon Wiesenthal enters the camps

Simon Wiesenthal dodged death a shocking number of times. In 1941, he was among those selected for execution, but the executioner went on break before reaching him. According to the Independent, it wasn't long after that he and his wife were confined first to a ghetto and then, to the Janowska concentration camp.

From there, he was moved to a satellite labor camp where he was first tasked with painting markers on the railway cars. Getting the attention of the camp's Nazi manager, he was then given what The Guardian calls "design work," and tasked with acting as the camp's liaison with Polish contractors — which gave him an opportunity to make contact with the Polish resistance, and ultimately arrange to have them smuggle Cyla out of the camps.

Death came knocking again on April 20, 1943: Hitler's birthday. As part of the birthday celebrations, Wiesenthal was selected — along with 19 other men — to be executed. His execution didn't come: instead, an SS corporal stepped in and said he needed Wiesenthal to paint banners for Hitler's birthday festivities.

A few months later, Wiesenthal escaped from the camp, with the help of an officer named Adolf Kohlrautz. Those two helping hands laid the groundwork for his later beliefs: at the same time he felt guilty — thinking he had done nothing to deserve the life he'd been given — he would also be a proponent of judging people on deeds, not nationality or race.

And back again

After just a short time in hiding, Simon Wiesenthal was recaptured by SS soldiers. What followed was a nightmarish parade of concentration camps, which The Guardian says started back at Janowska. When he got there, nearly all of the other prisoners had been killed or evacuated. According to the LA Times, there were only 34 men left — and their lives were spared by Commandant Friedrich Warzok, who let them live so they would need to be guarded... and so he and his men wouldn't be sent to fight.

From there, he was moved on to Plaszow, then Auschwitz... where they were already running the crematoriums at max capacity, so he was sent on to Buchenwald. By the time he was pushed onto a freight wagon for Mauthausen, he had seen the inside of 11 different concentration camps. He was sent to Mauthausen's death block: the place where the people who were going to die were sent to do so.

The concentration camp was liberated by the US 11th Armored Division on May 9, 1945. He later recounted, "I was hardly able to walk. I was wearing my faded striped uniform ... I wanted to touch the star, but I was too weak. ... I remember taking a few steps, and then my knees gave way, and I fell on my face. "Somebody lifted me up. ... the rough texture of an olive drab American uniform... I pointed to the white star, I touched the cold, dusty armor with my hands and then I fainted."

A post-liberation question: what now?

Simon Wiesenthal had arranged for his wife's escape from the camps in 1943. In exchange for drawing detailed maps that would be passed on to saboteurs, the blonde-haired Cyla was given a new identity as Irene Kowalska. According to the LA Times, he had been in Gross-Rosen when he met someone who knew her — as Irene. That's where he also learned Nazis had burned the street where she was living to the ground... and, they told him, there were no survivors.

Just two days after the liberation of Mauthausen, he was given another beating: this time, by a Polish trustee. He would later say (via the Independent) those were the blows that hurt the worst, because hate was clearly alive and well.

So, he went and offered his services to the War Crimes department of the US Army, and while he was first turned away — he was still incredibly weak — he returned 10 days later. They sent him to arrest an SS guard living in a nearby apartment building, so he did. It was just the start, but first, he wanted to give his wife a proper burial. He wrote and sent a letter to a lawyer in Krakow, and just a few days after the letter arrived, so did a shocking visitor: Cyla Wiesenthal. She was looking for her husband, and they were reunited.

Simon Wiesenthal's list of names

From even those first days, one thing in particular stuck with Simon Wiesenthal. It was a conversation with a corporal named Merz, who asked him what he would tell people if he escaped. He'd replied (via the LA Times) he would tell the truth, and Merz simply smiled and said, "You know what would happen, Wiesenthal? They wouldn't believe you. They'd say you were crazy. Might even put you into a madhouse." He decided he was going to make people believe him.

According to The Nation, it was 20 days after liberation that Wiesenthal completed and turned over an eight-page document to the Americans. On it were almost 150 names: they were Nazi war criminals responsible for the atrocities the Allies saw unfolding before them again and again, and he was going to do whatever he could to make sure they were brought to justice — and to make sure that the world believed what had happened.

The exact number of names varies, and according to The Guardian, he handed over a list of 91 names. They also say that ultimately, he had not only helped track down 75 of those people, but that he'd had a hand in assisting with tracking down and arresting more than 1,000 war criminals who had originally escaped Allied justice.

Odessa: the Nazi escape route

Wiesenthal's work first included figuring out how so many Nazi war criminals weren't just getting away, but heading to one particular area: South America.

According to the Jewish Virtual Library, it was on August 10, 1944, a group of Nazi industrialists, bankers, and tycoons met in Strasbourg to come up with a plan should things go sideways. They wanted to come up with a network that would allow people — and assets — to be transferred well out of Allied hands, and that was the Organization Der Ehemaligen SS-Angehorigen, or Odessa.

By 1947, Wiesenthal had helped to identify some of the routes Nazi war criminals were using to escape arrest in Europe, and that meant outing people like Alois Hudal, an Italian bishop who oversaw a monastery — Via Sicilia — described as a "transit station for Nazis." Roman Catholic priests in particular were called out for helping move Nazis through Europe to safety, and later research that built on Wiesenthal's work uncovered other complicit organizations, including (via The Irish Times) the International Red Cross.

Simon Wiesenthal vs. Adolf Eichmann

There were a lot of names on Simon Wiesenthal's list, and according to the Independent, Adolf Eichmann was at the very top. It was Eichmann who had overseen the logistics of transporting people, sending millions to their deaths and making sure the trains to the death camps kept on running. By all accounts, he loved what he did: he kept things going even after Heinrich Himmler ordered top Nazis to go into damage control mode and start destroying evidence.

After going into hiding in a Catholic monastery in Italy, Eichmann eventually headed to South America — and about the same time, Wiesenthal set up the Jewish Documentation Centre in Linz. Through that, he dug up witnesses who testified Eichmann was still alive and prevented his wife from having his death certificate issued.

Things didn't go great for Wiesenthal after that — the Cold War and a lack of funds meant his center closed. Years went by, and Wiesenthal heard rumors Eichmann was living in Argentina. It wasn't until 1959 that Israel and the Mossad got wind of his alias — Ricardo Klement — and organized a mission to go arrest him. They did — in 1960. He was put on trial, convicted, and hanged on June 1, 1962. Wiesenthal wrote an entire book about his hunt for Eichmann, but the LA Times reported it wasn't without controversy: years later, Isser Harel — the head of the team who ultimately arrested Eichmann — later made it clear "Wiesenthal's role was absolutely nothing."

The Stomping Mare

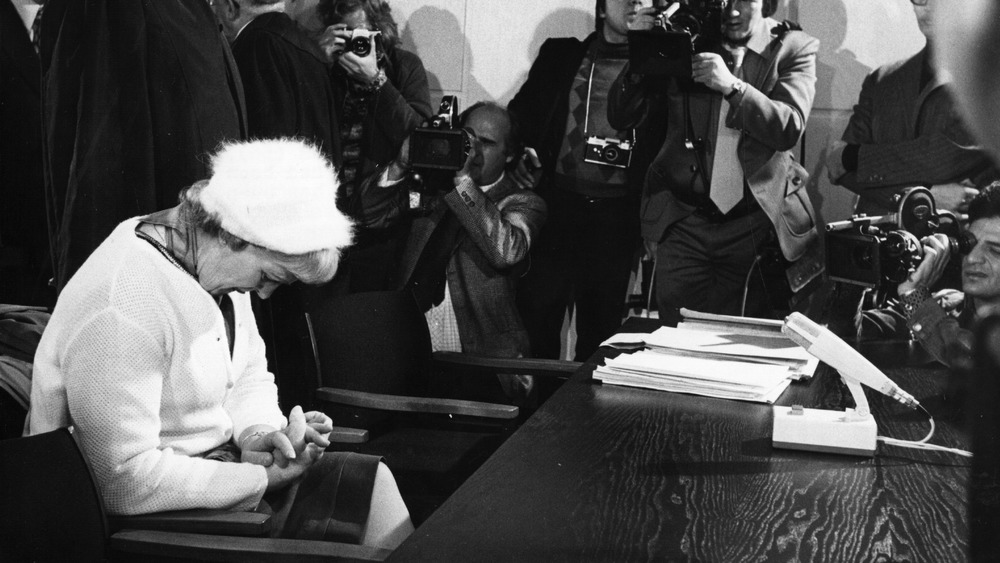

It was 1964, says The New York Times, that Simon Wiesenthal was approached by three people who had survived the horrors of Majdanek, a concentration camp the Jewish Virtual Library says was noted for its location in the wide open, clearly visible by to anyone who had driven past it on the main road. They told him about a guard they'd called Kobyla — Polish for "mare — who had been particularly cruel... and who had escaped justice.

Survivors testified that she had earned her name "Stomping Mare" because of her tendencies to stomp old women to death with her heavy boots. They described her whipping women until they were dead, and grabbing children and girls by the hair and throwing them onto the trucks that were waiting to take them to the gas chambers.

So Wiesenthal and his assistants started looking, and ultimately tracked her to Halifax. From there, they found she had moved to Queens, information that was passed on to a Times reporter. They didn't have an exact address, though, but when he started knocking on doors, he found her — and she admitted that she was the Hermine Braunsteiner of Majdanek. She was extradited to West Germany, put on trial in 1975, and in 1981, she was given a life sentence. After developing diabetes and losing her leg, she was released in 1996 and died in 1999.

The man who arrested Anne Frank

Simon Wiesenthal was living in Linz, says Politico, when he attended a theater production of The Diary of Anne Frank. The audience was filled with hecklers who made it very clear they thought the whole thing was a hoax, and afterwards, Wiesenthal talked to some of them. It was one high school student in particular who claimed Anne Frank wasn't real and the diary was simply a work of fiction. Even Frank's father was thought to be faking, but there was one person whose testimony the boy said he would accept: the Gestapo officer who arrested them. So, Wiesenthal made it a point to find the man, even though the only lead he had was in the appendix of her diary. There was a mention of a man who had a last name that started with something that sounded like "silver," and it wasn't until 1963 that he had a breakthrough.

Wiesenthal got a copy of a phone directory that included Gestapo officers working in that area at the time the Franks were arrested. One of the names was Karl Silberbauer (pictured), and he admitted it had been him. When confronted, he simply said, "Why pick on me after all these years? I only did my duty."

According to the Independent, Austrian authorities agreed. After a brief investigation, Silberbauer — who had been working for Vienna's police department at the time — was cleared of charges and was found to have just been doing his job.

Simon Wiesenthal wasn't without controversy

It's worth noting that there was a fair share of controversy around Simon Wiesenthal, his claims, and his methods. According to The New York Times, the impression he liked to give — that he was at the head of some massive organization that dished out justice on a daily basis — just wasn't accurate. More often, they say, it was him — alone — sifting through mountains of papers, books, documents, and phone records, then turning over the evidence he found to those who did the actual arresting. Which is still pretty impressive.

Still, there was a dark side. Cyla was described as a "sickly, depressive woman," once quoted as saying, "I am not married to a man. I am married to thousands, maybe millions, of dead." Spiegel says there were other issues people had, too. Wiesenthal, they write, was often accused of exaggerating the role he played in apprehending fugitives, and in doing so, was also accused of liking fame and glory more than the actual justice.

Along the way, they add, they say he was known for his questionable methods of collecting information, ignoring instances where he was wrong, antagonizing those who were trying to do the same thing he was — including other Nazi hunters. Biographer Tom Segev wrote that although he was a "brave man," he was also possessing a "soaring ego" and a "tendency to fantasize."

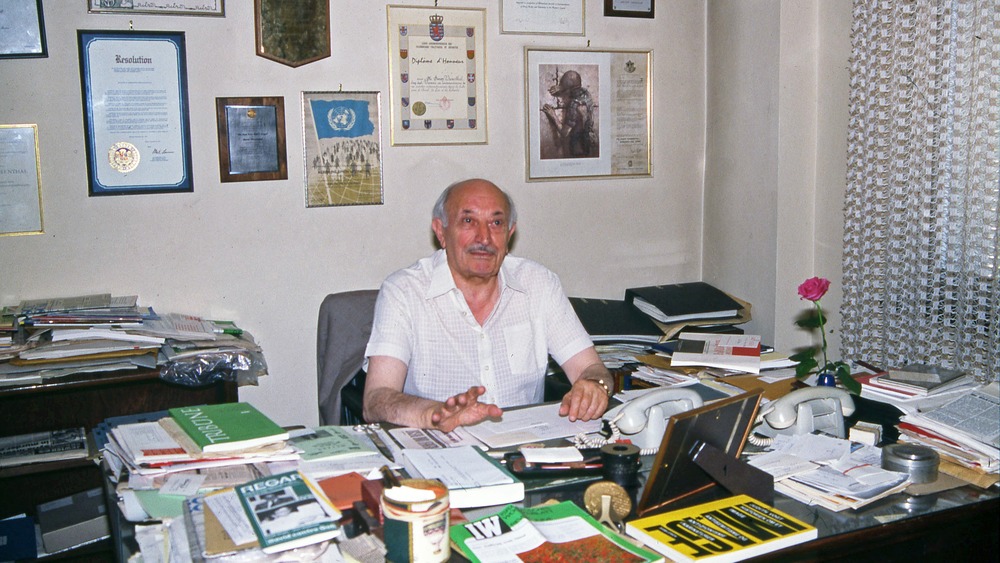

Simon Wiesenthal says he never retired

In 2001 — when Simon Wiesenthal was 93-years-old — The Guardian visited him at his offices in Vienna. There was a rumor that he was retiring, but he made it clear that wasn't exactly true. What he had said was, "I have survived the majority of all the people I have searched for in 50 years. And now I am not searching for more people."

But he wasn't done — he added that he was refocusing on documentation, because the records and stories of those who had lived through it were just as important. In 1980, he told President Jimmy Carter: "There is no denying that Hitler and Stalin are alive today... they are waiting for us to forget, because this is what makes possible the resurrection of these two monsters."

He continued his work for several more years. In 2003, Rabbi Paul Chaim Eisenberg announced (via the LA Times) that Cyla Wiesenthal had passed away at 95-years-old. Two years later, Rabbi Marvin Hier announced (via the LA Times) the passing of Simon Wiesenthal, who had suffered from consistently declining health since Cyla's death. He was 96, and left behind this message: "When history looks back, I want people to know the Nazis weren't able to kill millions of people and get away with it."