The Gruesome Story Of The St. Valentine's Day Massacre

The United States Prohibition era created quite a mess for the 1920s and early '30s. The bootlegging trade provided alcohol to the thirsty masses while putting money in the hands of the wrong people. The only positives were giving moonshiners a reason to perfect their craft and providing story fuel for innumerable films, then and for decades to come. Sure, speakeasies and jazz are pretty cool, but criminal penalties for raising a Manhattan to good health certainly balanced all that out.

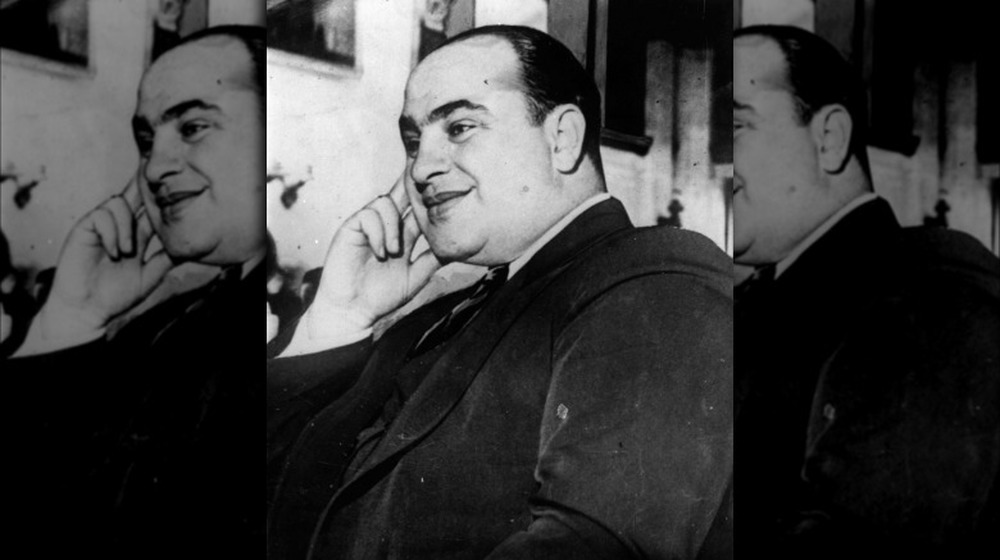

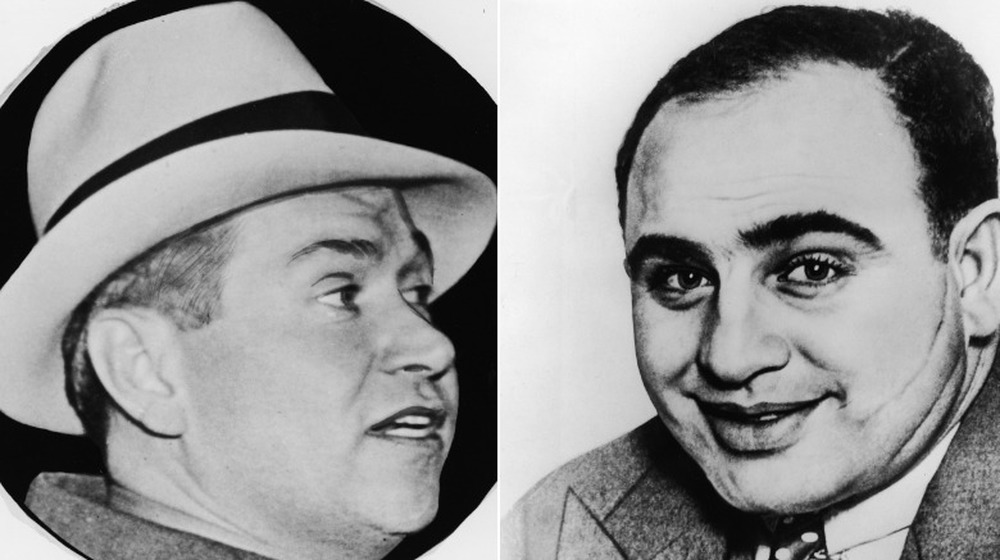

Along with the music and expertly hidden watering holes, the Prohibition Era also gave birth to mobsters. Modern western culture has a thing for romanticizing these crime bosses. They've become staples of popular culture, and no crime boss was more famous than Al Capone — "Scarface" (a nickname he hated, by the way).

Capone has been immortalized thanks to a couple of noteworthy films, but the real deal would've made latter-day fans think twice before throwing their praise. As charming as Capone was in front of the camera and to reporters, he's believed to have killed enough people to make anyone sick, and he did it all for power and cash. Being on Capone's bad side wasn't somewhere you wanted to be, and the St. Valentine's Day Massacre is generally believed to be the most prime example of this. The execution-style killings were an attempt by Capone (or so it's believed) to "take care of" his long-term rival, Bugs Moran. Here's how it all shook out.

Al Capone had a history of making his rivals disappear

Al Capone wasn't exactly known for taking it easy on the opposition. According to History, the Capone gang's kill count reached as high as 64 murders in a single year. If Capone had eased off, there's a good chance he wouldn't have been worth roughly $100 million (and that's in 1920s money). Messing up Capone's business and running booze in the same area as Capone's gang — pretty much all of Chicago — was asking to be killed. Oddly enough, Capone's "snuff out the competition" attitude is exactly what put his rival crime boss, George "Bugs" Moran, in power in the first place.

Moran, as Britannica explains, was the right-hand man to one Dion O'Bannion, a notorious gangster and previous rival to Al Capone. Long story short: Al Capone didn't like O'Bannion's hold on the Northside liquor trade in Chicago, so he sent a few of his goons to O'Bannion's flower shop (sweet cover for a mob boss, right?), and the aforesaid goons whacked him, says Britannica. This slingshot Moran to the top of the O'Bannion gang, and he picked up right where his late friend and employer left off. Capone didn't like that, either.

A little trickery goes a long, bloody way

As far as mass murders go, the St. Valentine's Day Massacre is one of the trickiest, best-crafted slaughters of the 1920s. The year was 1929; the day was Valentine's Day, and all was quiet in Bugs Moran's place of operation, the SMC Cartage Co. garage, located at 2122 North Clark Street in Chicago. Moran's men were hard at work, presumably putting together an order of illegal liquor for a paying customer, when a car rolled up and four men, two of them dressed as police officers, popped out.

Moran, according to Britannica, was heading to the garage when he saw the police car arrive. Being the astute crime boss he was, Moran decided to get out of there so he wasn't caught in what he believed to be a raid. Moran's boys also must have thought it a raid, seeing as the four faux police officers had no trouble rounding up the seven armed gangsters and convincing them to line up against the wall. According to Chicago Mag, not a single one of Moran's men reached for a weapon. That was it. They were all in place. The four invaders, believed to be Capone's men, opened fire.

Witnesses on the street could hear the rapid clack of two Thompson submachine guns and a shotgun as they tore Moran's crew apart. Though Moran himself escaped the massacre, the incident put an end to his mob boss career.

[Featured image by David via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 2.0]

The last words of Frank Gusenberg

Amid the heap of bodies, police discovered one lone survivor from the massacre: Gangster Frank Gusenberg (via the Daily Telegraph). Gusenberg lived for a few more hours but he gave very little away. It probably didn't help that he had 14 bullets lodged in his flesh and was not feeling particularly talkative. When the police asked him about the perps he simply replied: "No one. Nobody shot me."

Gusenberg's refusal to name his killers may sound surprising, but like many other gangsters, he was probably adhering to the omerta — a code of absolute silence that a few noble-minded mobsters used to follow (via the Daily Mail). Maintaining a stony face, just before he expired he told questioners "I ain't no copper."

Or at least that's one version of events — there is a second story that may or may not be true but that was reported in one newspaper at the time. According to this second account, Gusenberg told Police Sergeant Thomas J. Loftus that cops were responsible for the killing (via "Get Capone", by Jonathan Eig, 2010). Based on his words some people were led to believe that the deeply corrupt prohibition-era police — rather than men dressed as police — were the real culprits. However, it's not much to go on, and to date, it has never been proven.

Al Capone's killer: Machinegun Jack

Immediately after the murder, the cops thought the killing could have been the work of Al Capone's notorious hitman and bodyguard, Jack McGurn — better known as "Machinegun" Jack (via "Get Capone," by Jonathan Eig). However, when investigators interviewed McGurn he accused the police of being involved and then brushed them off by saying, "Don't make me laugh! The Gusenberg boys would have plugged me if they saw me a block away." Despite his scoffing McGurn did have a strong motive to go after Frank and Peter Gusenberg — they'd tried to kill him personally about a year before the massacre (per the Mob Museum).

Regardless, the case against McGurn never went anywhere because it turned out he had a pretty strong alibi. According to The Independent, his girlfriend Louise Rolfe was willing to claim she spent the whole day with him. True or not, to prevent the authorities from interrogating her further, the pair got married — and McGurn got off.

While it is possible that McGurn was not involved in this particular bloodbath, somebody with a grudge seems to have believed he was. Exactly seven years and one day later, on February 15, 1936, McGurn was found riddled with bullets at a Milwaukee bowling alley. According to legend, a cryptic note delivered by the killers read, "You lost your dough and handsome houses, but things could be worse, you know, at least you haven't lost your trousers."

The Purple Gang Theory

According to the Detroit Historical Society, following the murder, the police also investigated a group of mobsters allied with Al Capone: the notorious Purple Gang who had their own bootlegging outfit in nearby Detroit. The Purples were a group of assorted immigrants who'd settled in Detroit in a district called Little Jerusalem, and they had a terrifying reputation locally for a whole host of crimes — from running prostitutes to robbery to kidnapping, per the Detroit Historical Society. Because of their fearsome notoriety, cunning Capone decided to use their Canadian smuggling route as part of his own operation rather than starting a rivalry.

At the time of the massacre, a local woman reported that at least three of the Purples had rented a room suspiciously close to George Moran's garage (via "Get Capone," by Jonathan Eig). It is possible they were hired to observe Moran, even if they were not directly involved in the shooting itself. Alternatively, some police at the time believed that Moran's gang had crossed the Purples themselves after they foolishly stole one of the gang's whisky vans.

At that time, the Purples were already guilty of at least one other mass murder — the Milaflores Massacre of 1927 — and they are believed to have killed at least 500 people while they were in operation.

Fred Burke's guns

At least one of the killers was almost certainly correctly identified as Fred "Killer" Burke, an ex-Purple Gang member and friend of Al Capone, per the Mob Museum. Burke was an extremely unpleasant character, already connected to several other murders and with a criminal history a mile long. Burke disappeared shortly after the St Valentine's Day Massacre, strongly suggesting he had something to hide.

Not only was Burke known for dressing as a policeman when committing felonies, but witnesses at the scene of the massacre also stated he was present (via "A Brief History Gangsters," by Brian J. Robb). However, authorities only picked up Burke's trail many months later, after he shot a policeman during a traffic accident. At the time, he was using a fake name and laying low in Michigan. After the police raided Burke's house they found two tommy guns whose bullets matched those used in the Valentine's Day Massacre.

Burke ran again — this time to Missouri, where he was eventually turned in by a suspicious local. Despite some pretty damning evidence, he was never convicted for the St Valentine's Day killings — but he did end up in prison anyway, for murdering a cop.

Byron Bolton and the American Boys

In 1935, notorious gangster Byron Bolton was arrested in an FBI raid, according to "American Mafia: Chicago," by William Griffith. While in custody he made a shocking confession — he had been one of the lookouts at the St. Valentine's Day Massacre.

Today some people believe that Bolton's confession was complete fiction because some of the suspects he named had alibis. However, the story he told was pretty convincing and seems to line up with the rest of the available evidence (via "Get Capone," by Jonathan Eig). According to Bolton, the shooting was committed by Al Capone's "American boys," a group of mobsters with strong connections to the city of St Louis. The Mob Museum claims that the men Bolton named included Fred Burke, Bob Carey, Gus Winkler, Raymond Nugent, and Fred Goetz. Winkler in particular was murdered by the mob at a later date, allegedly for talking to the FBI, and all the other group members were dead by 1934, a year before Bolton blabbed.

Bolton's fascinating story contained some interesting details. For example, he mentioned that the crew had screwed up the murder because Bolton himself had misidentified one of the men at the garage as George Moran. Rushing in too soon they shot up the place and missed their target. The wives of both Winkler and Goetz told much the same story as Bolton at a later date, and the gangster's confession remains the most plausible explanation.

A back and forth game

You'd think a mass murder as straightforward and deadly as the St. Valentine's Day Massacre would've led to Al Capone's arrest, but the elusive crime boss had an iron-clad alibi. At the time of the shooting, according to Chicago Mag, Capone was hanging out in the courthouse of Dade County, Florida. He was on a vacation of sorts, having traveled down the East Coast to meet with a prosecutor who was investigating the murder of a different crime boss in New York.

George Moran knew exactly who had slaughtered his men in the failed attempt to get rid of him once and for all. In an interview, the now crewless mob boss had a few choice words for reporters. "Only Capone kills like that!" he yelled, according to History. When Capone was interviewed about the massacre shortly after, he responded with a smug smile on his face, saying, "The only man who kills like that is Bugs Moran." The comment was an obvious taunt at his defunct business rival.

It would seem that Moran got a modicum of revenge for the slaughter when he (possibly) murdered one of Capone's men — more specifically, one of the men who had fired on his crew. But Moran was never proven to have been behind that killing. On the brighter side (if there is a brighter side), the guy outlived Capone by a decade, so that's something, right?

The stick that broke the mob boss's back

Al Capone was never convicted of the crime, even with, as Chicago Mag explains, the mob boss's cocky side running unchecked. Capone bragged left and right about his airtight alibi. After all, he was sitting down with a prosecutor, which is pretty much the epitome of a verifiable alibi. Whether or not Capone committed the crime wouldn't matter to the country. The St. Valentine's Day Massacre was crossing the line, and law enforcement began to double down. The heyday of organized crime was over.

President Herbert Hoover (pictured above) took office less than a month after the massacre, and one of the first things he did was warn the country about the growing threat of organized crime. He needed to make an example out of a powerful gangster to get the country back on track, and he set his sights on Capone. Hoover urged the authorities to find the evidence that would link Capone to the slaughter, but nothing solid turned up. Instead of charging the crime boss as an accessory, since it wouldn't stick anyway, Hoover had to find a different route. Capone would finally be put away in 1931 for tax evasion and was never officially linked to the massacre. There are several theories on who may have killed George Moran's men that day, and only one involved Capone. Maybe he really was innocent. Not that it mattered. Moran's men were still dead.

The unlikely revenge of three-fingered Jack

There are some people who maintain that the St. Valentine's Day Massacre had nothing to do with Al Capone at all. "Get Capone," by Jonathan Eig, puts forward an alternative explanation based on a letter sent to the FBI in 1935, which claimed that the massacre was a revenge killing committed by mobster William White.

White was a hardened criminal, known to his associates as "Three-Fingered Jack" for his mangled right hand. It is believed he may have worked with the Gusenberg brothers on a heist at some point, but the Gusenbergs later got on White's bad side when they shot his cousin, William Davern, in a bar fight. Curiously, Davern's father was a cop — which may explain the police uniforms used on the job.

According to the mysterious letter, although White was supposed to be in prison on the day of the murders, he bribed his way out of jail to execute the plot and get his revenge (via ABC7). This version of events does not explain some of the other evidence that points to Capone's men; however, it does explain why nobody seemed to care that mob boss George Moran, the supposed target of the hit, walked away unscathed.

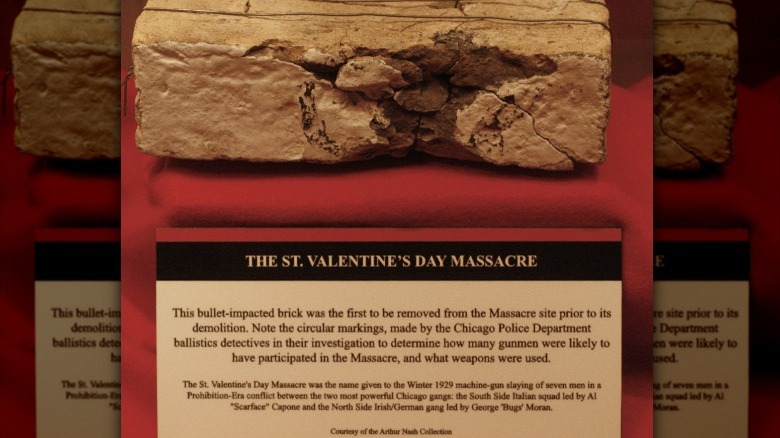

Remnants of a murder

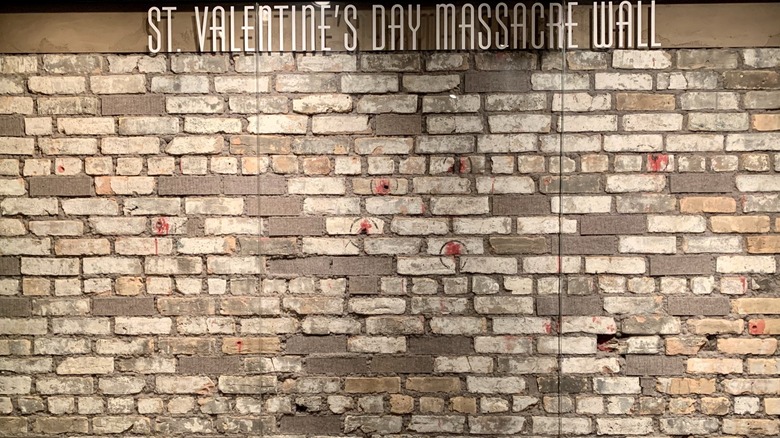

As the years flew by, the Valentine's Day Massacre became part of pop culture. By 1932, Al Capone had been made the subject of the classic movie "Scarface," and incredibly, by the 1950s, the massacre itself had become a joke in the comedy classic "Some Like it Hot" (via Mob Museum).

Perhaps unsurprisingly, by the '50s, the infamous garage wall against which the shooting took place had a very weird afterlife as a tourist attraction, notes Chicago Detours. Morbid visitors regularly went to visit the building even after it had been converted into a furniture store. Although the building was eventually knocked down, the bricks were carted away for safekeeping by George Patey, who took the bloody blocks on tour. After seeing the world (or rather Canada), he later reassembled them to make a wall in his mobster-themed nightclub.

By the '90s, Patey decided to sell the bricks. Many of the bricks were later acquired by the Mob Museum in Las Vegas, where you can still see them today — the bullet holes are real, but the blood is fake. The site of the murder in Chicago on the other hand is now an empty parking lot — still haunted by tourists.

[Featured image by APK via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 4.0]