The Crazy-True Story Of The Rebellion That Inspired The Racial Slave Codes Of 1705

Bacon's Rebellion is considered one of the main events that ushered in racial enslavement in the American colonies and later the United States. And while it's true that the rebellion influenced the increasing addition of slave laws that distinguished between non-white and white, Bacon's Rebellion simultaneously embodied the existing distinction between native and non-native.

The rebellion arose out of a desire to commence a genocidal campaign against the Indigenous groups that lived in the area by the Chesapeake Bay. And Nathaniel Bacon's inclusion of free and indentured Blacks wasn't out of a desire for racial equality but purely out of a desire to have more fighters.

As a result, Bacon's Rebellion was ultimately both a failure and inadvertently successful. Without meaning to, it developed "the use of landless or land-poor settler-farmers as foot soldiers for moving the settlement frontier deeper into Indigenous territories," though Bacon wouldn't live to see it.

After the rebellion's failure, the Virginia government started expanding the institution of Black enslavement while "slowly eliminating white indentured servitude." As a result, Bacon's Rebellion becomes a point of intersection between various origin stories of oppression. This is the crazy true-story of the rebellion that inspired the racial slave codes of 1705.

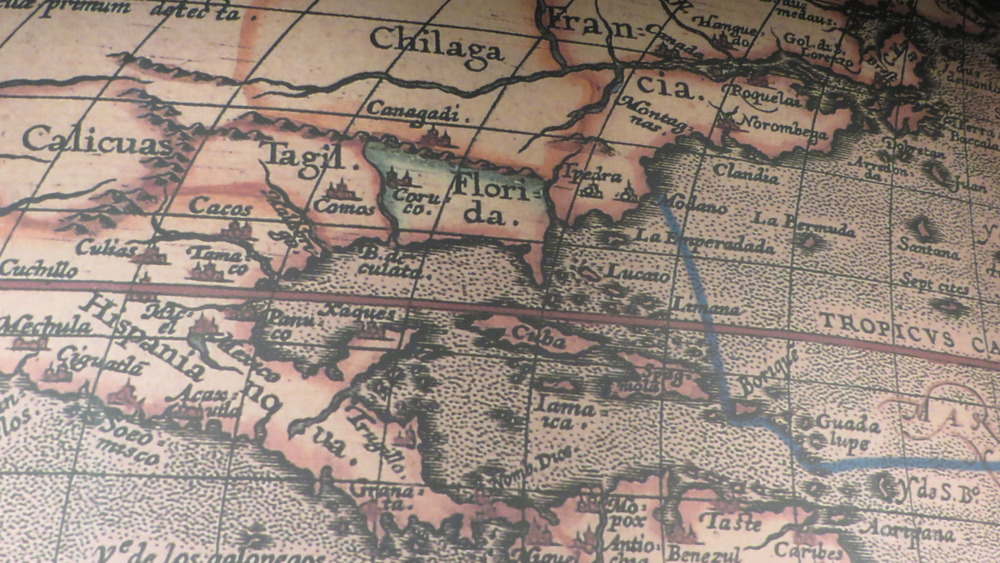

Claiming the colony by Chesapeake Bay

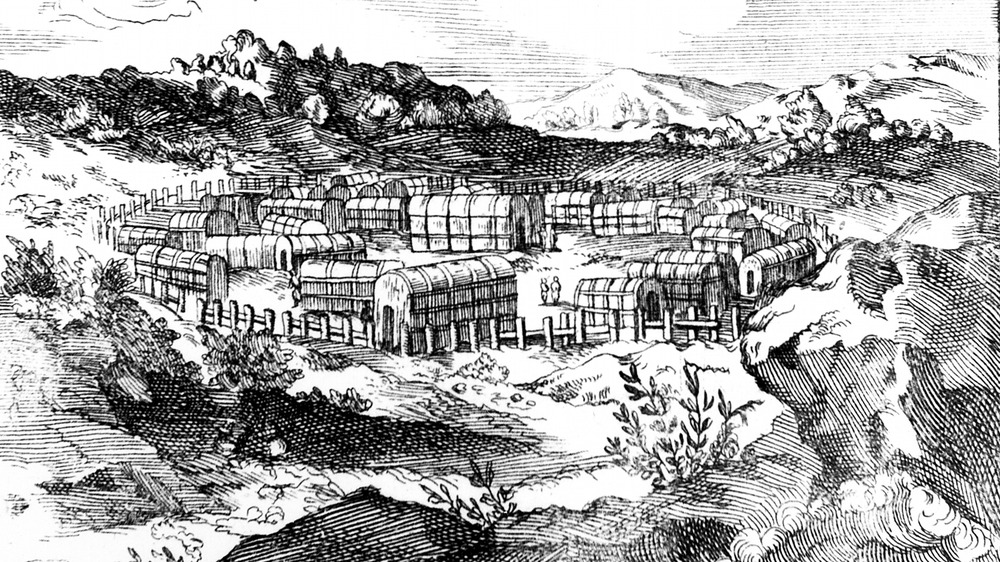

Before the English settlers arrived in what they called Jamestown in 1607, the area was inhabited by multiple Indigenous groups, including the Powhatans, the Rappahannock, the Patawomeck, the Doeg, the Susquehannocks, and the Opechancanough.

According to An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States, by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, the Jamestown settlers lost no time in encroaching on the native peoples' land and beginning a campaign of terrorism. After the Powhatan Confederacy refused a demand to provide settlers with food, the settlers started a war, targeting women and children. When the settler population was unable to eliminate the Indigenous population through warfare, they resorted to a "systematic destruction of all the Indigenous agricultural resources," stealing what they could from corn fields and burning the rest.

Even when settlers did legally purchase land from the Rappahannock, it took the Rappahannock ten years to get a fraction of the payment, and it was never paid in its entirety. In 1665, legislation was also passed that gave the colony's assembly the authority to "choose each tribe's leader."

Enslavement of Indigenous people

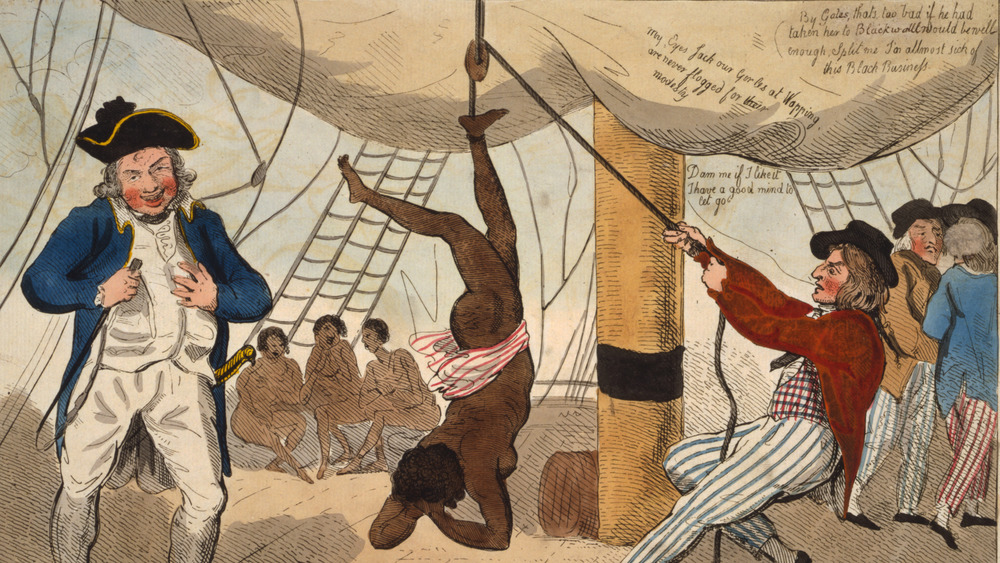

Settlers in Virginia were soon enslaving Indigenous people whom they captured during wars. While some native people who were enslaved remained in the Virginia colony, others were trafficked to the Caribbean during and after the Third Anglo-Powhatan War from 1644 to 1646.

According to Indian Slavery in Colonial America, edited by Alan Gallay, from 1645 to 1650, at least 28 Indigenous people were claimed "on colonial deeds and inventories as either servants or slaves," although at least six are "unambiguously slaves." Comparatively, Africans in Virginia were indentured servants until 1661, when slave laws were passed, legalizing enslavement for any free person, "white, black or Indian." According to Smithsonian Magazine, before the passage of slave laws, captured people who were brought to North America became indentured servants. If they were taken anywhere else, they became enslaved.

Comparatively, native people were immediately enslaved and exported. Although the Treaty of Necotowance prohibited the enslavement of "allied" Indigenous people, it didn't mention "hostile" or "foreign" Indigenous people.

During the Third Anglo-Powhatan War, William Berkeley, the colonial governor of Virginia, bought at least two young Indigenous people from Lt. Thomas Smallcombe, whose estate enslaved at least six other Indigenous people. Indigenous children were often enslaved "under the guise of servitude."

The price of freedom

Without the existence of slave laws, people were initially indentured servants in North America. According to PBS, although their lives were incredibly difficult, those who survived were able to pursue a life outside of indentured servitude. A small minority even managed to become part of the "colonial elite." Some laborers, however, had their contracts repeatedly bought and sold and never attained freedom. The period of indenture could also be extended as a form of punishment. In Virginia, if women who were indentured servants became pregnant, their contract could be extended by two years.

In Virginia, the first slave law was passed in 1661, when enslavement was given statutory recognition by ruling that if African slaves and indentured servants ran away together, then the English servant shall "serve the masters of the said negroes for their absence soe (sic) long as they should have done by this act if they had not beene slaves."

According to Smithsonian Magazine, one of the first "slaves for life" in Virginia was John Casor, an African man who was captured and brought to North America. In 1654, Casor claimed that he'd long completed his working contract under Anthony Johnson and demanded his freedom. Johnson had also been captured and brought to North America from Angola but had gained his freedom from indentured servitude around 1635. But when Casor claimed a similar courtesy, Johnson denied his request, took Casor's new employer to court, and Casor became Johnson's lifelong slave under law.

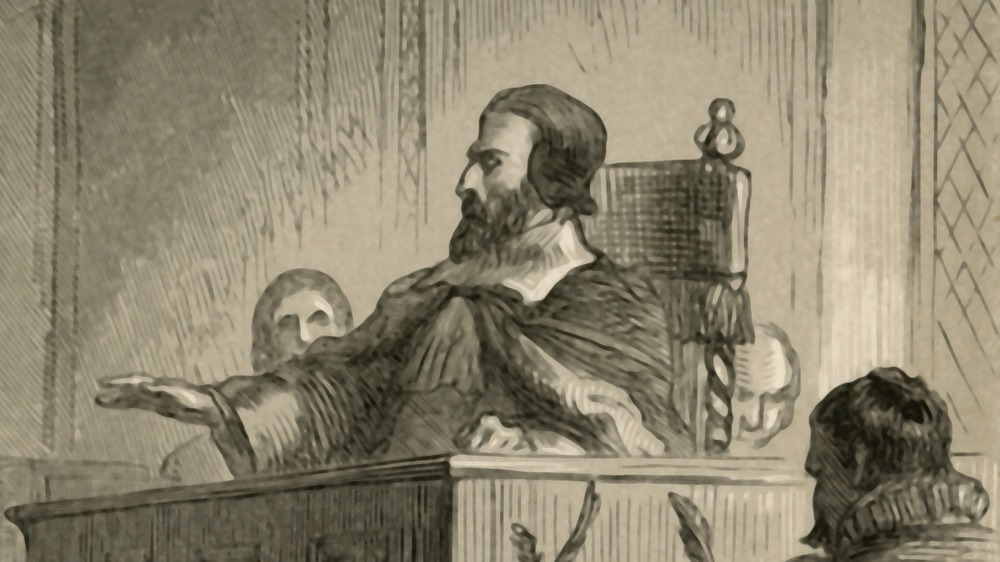

Who was William Berkeley?

Sir William Berkeley was a British colonial official who served as the colonial governor of Virginia for two periods, from 1642 until 1652 and from 1660 to his death in 1677. According to Encyclopedia Britannica, after growing up in England and being knighted in 1639, Berkeley was appointed Virginia's colonial governor in 1641. Unfortunately, his loyalty to Charles II is what led to his forced abdication of the governorship from 1652 to 1659.

Arriving in Jamestown in 1642, Berkeley quickly sought to diversify Virginia's agricultural products and began experimenting with alternatives to tobacco, such as flax, rick, and fruits. Although he was successful during his first years as governor, his second period as governor was impaired by crop failures, economic depression, high taxes, and a power play by his cousin by marriage, Nathaniel Bacon.

According to Encyclopedia of U.S. Labor and Working-Class History, by Eric Arnesen, Berkeley also stifled elections and "discouraged widespread education," which led to increasing resentment against him by the settlers who didn't support him. Settlers were also irritated that Berkeley refused to take military action against the Indigenous groups who were continuously resisting the advances of settlers and retaliating against settler attacks. While Berkeley wasn't any more sympathetic towards Indigenous people than the other settlers, "he had lucrative trade interests with the Natives to protect."

During Berkeley's second period as governor, the General Assembly ruled in 1662 that a child's "slave or free status would follow the condition of the mother."

Attacking the Occaneechi people

One of the sparks of Bacon's Rebellion was a group of settlers' refusal to pay for hogs in 1675, even though it occurred a year before the rebellion. According to Revolts, Protests, Demonstrations, and Rebellions in American History, by Steven L. Danver, the year before Bacon's Rebellion, the settlers began battling with the Doeg and Susquehannocks after the settlers refused to pay for the hogs they'd purchased. Setting off the Susquehannock War, the Virginian government destroyed several Susquehannock villages, while the remaining Susquehannock groups started indiscriminately raiding the outlying settlements of Virginia.

While William Berkeley wanted to plan a series of frontier forts and patrols for the settlers to defend themselves against the attacks, Nathanial Bacon decided to go on the offensive. After repeatedly requesting from Berkeley an expedition and being refused, Bacon decided that he didn't need permission for a killing spree.

According to Encyclopedia Virginia, Bacon gathered a group of volunteer militiamen and went after the Susquehannocks. Encountering the Occaneechi, he persuaded them to attack the Susquehannocks for him. After the Occaneechi came back with Susquehannock prisoners, Bacon and his men began killing Occaneechi indiscriminately, murdering at least 150 people.

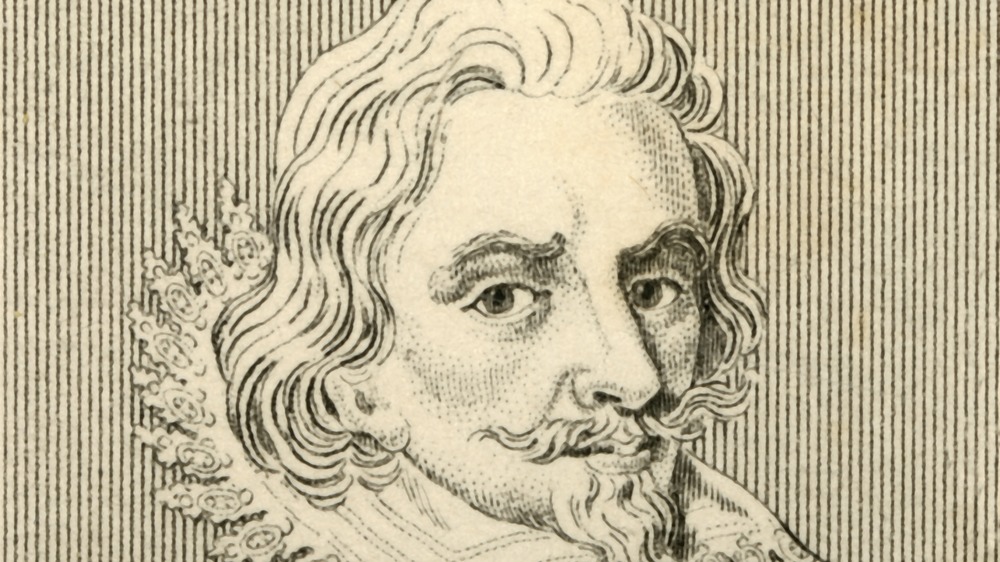

Who was Nathaniel Bacon?

Nathaniel Bacon was born in England in 1647 and arrived in Virginia in 1674. However, migrating to the American colonies wasn't always part of his plan. According to The 17th and 18th Centuries, edited by Frank N. Magill, after Bacon married Elizabeth Duke in 1673, she was disinherited due to her father's opposition to the marriage. Meanwhile, Bacon got caught up in a scheme to defraud a friend, and when the details of the plan became public, Bacon's father gave him 18,000 pounds to leave and go to the American colonies in order to avoid a scandal.

Within a year, Bacon was appointed to the governor's council thanks to his financial means and his relation to Gov. William Berkeley. But soon, Bacon grew tired of Berkeley's cautious policies towards raids by Indigenous groups and decided to take matters into his own hands.

Berkeley soon declared Bacon a rebel and removed him from the council after the killing spree against the Occaneechi. Bacon appeared to be willing to reconcile with Berkeley when he was arrested upon his return, and Berkeley allowed him to return to his position of power. But when he was once more refused the right to mount an expedition against Indigenous groups, Bacon assembled his own 500-man volunteer army.

The Declaration of the People

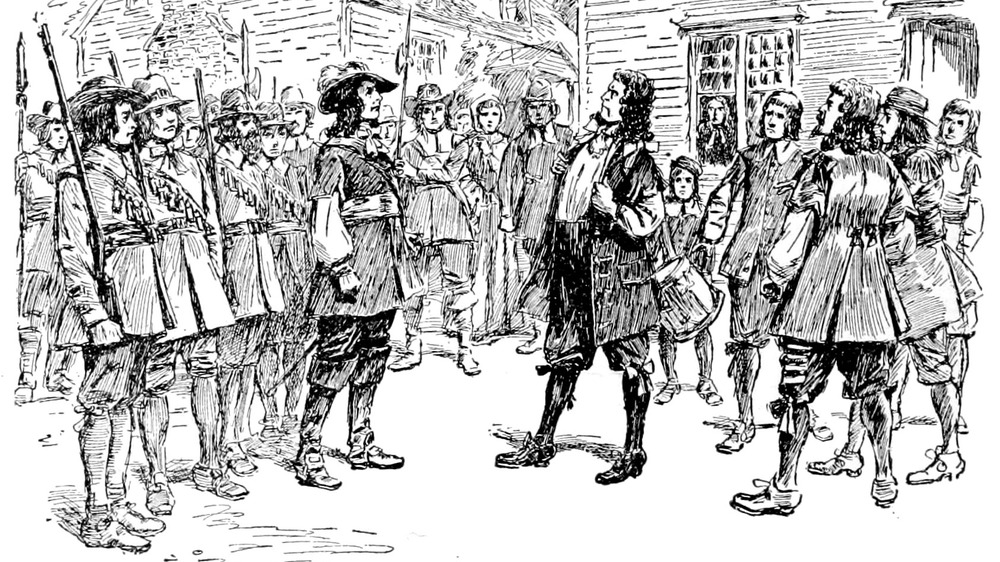

With his 500-man army surrounding the statehouse, Nathaniel Bacon intimidated officials into declaring Bacon the "commander in chiefe (sic)" in the war against Indigenous people on June 23 1676. But by late July, Gov. William Berkeley once again claimed that Bacon was a rebel and a traitor who had to be stopped.

In response to this, Bacon issued The Declaration of the People, which listed the various complaints that the settlers had against Berkeley. In the declaration, Bacon claimed that Berkeley was corrupt and protected Indigenous people for his own interests, repeatedly betraying the interest of "his Majesty's most faithful subjects."

According to The 17th and 18th Centuries, edited by Frank N. Magill, Bacon also simultaneously directed "the fury of his followers on the Pamunkey tribe." Although it took weeks of searching, to the point where "Bacon's soldiers began to look ineffectual, even inept," Bacon's soldiers unfortunately managed to stumble upon the Pamunkey in early September, capturing 45 people while murdering and scattering the rest.

After Berkeley declared Bacon a rebel, Bacon and his troops marched to Jamestown and took it over while Berkeley and his supporters fled east to Virginia's shore.

A diverse alliance

Despite being exceptionally anti-native, Bacon's Rebellion has been lauded for its diverse alliance of white and Black indentured servants, enslaved people, and poor free people in an attempt to overthrow the elite class of planters. According to An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States, by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, Nathaniel Bacon's supporters also included financial backers of wealthy planters whose interests were opposed to William Berkeley's.

According to The State of the American Mind, by Amechi Okolo, Bacon's Rebellion was the first time that "various poor exploited classes of all races in colonial America banded together against the elites and the colonial government." And although Bacon may have simply tried to rally various support by proclaiming freedom to all those who joined his army, regardless of the reason, the rebellion demonstrated a class unity that worried the Virginian elites.

According to A People's History of the United States, by Howard Zinn, the fear that "discontented whites would join Black slaves to overthrow the existing order" was the greatest fear at the time. Before and after Bacon's Rebellion, laws were passed in various colonies to punish Black and white people who engaged in relations with one another or escaped together. In 1691, Virginia passed a law that required banishment for any white person who married anyone non-white. Ultimately, Bacon's Rebellion demonstrated the potential for class unity that Virginian elites had to dismantle by introducing racial disunity.

Burning Jamestown to the ground

Although Nathaniel Bacon was able to drive William Berkeley out of Jamestown, he knew that his men couldn't hold it against the governor's forces. So on Sept. 19, 1676, resolving not to let Berkeley have Jamestown, Bacon set Jamestown on fire. As Berkeley and his men watched from downstream, homes, warehouses, taverns, and the statehouse went up in flames. Bacon himself had resolved to "laye [Jamestown] level with the Ground." According to the Dictionary of North Carolina Biography, edited by William S. Powell, William Drummond, one of Bacon's chief advisers, saved several provincial records from the statehouse before setting it on fire. Drummond was also one of Bacon's men who set fire to his own house in order to convince the rest of Bacon's men to burn Jamestown to the ground.

According to Colonial American History Stories – 1665-1753, by Paul R. Wonning, with Jamestown burning, Bacon and his men, still roughly 500 strong, set off into the forests searching for Indigenous groups "to slaughter and plundering homes of loyalists." Although Bacon tried to convince people to capture Berkeley, few undertook his appeal.

Jimson Weed intoxication

While William Berkeley and his men waited for British reinforcements in order to subdue Bacon's Rebellion, some of his men ended up accidentally poisoning themselves with Jimson Weed. Jimson Weed, also known as Jamestown weed, is a toxic plant that contains a variety of deliriant chemicals in all its parts, from root to petal.

According to Lapham's Quarterly, a number of Berkeley's soldiers made a soup using Jimson Weed and were soon struck by its hallucinogenic ability. For at least 11 days, the men behaved like monkeys and ran around naked. At one point, they even "wallowed in their own excrements." The men were isolated so as not to harm one another, and although the men came back to their senses after 11 days of hallucinations, none of them could remember any of their antics.

As a result, the weed was named after Jamestown, though it's also known as The Devil's Trumpet due to its toxic qualities and the shape of its flower's bloom.

Death from dysentery

All was seemingly going well for Nathaniel Bacon until October 26, when he died suddenly of "Bloodie Flux" (dysentery) and "Lousey Disease" (body lice). Since his body was never found, it's presumed that his soldiers burned the body. According to Bacon's Rebellion, 1676, by Thomas J. Wertenbaker, William Berkeley gloated heavily over Bacon's death, writing that the epitaph by an "honest minister" went, "Bacon is dead, I am sorry at my heart/ That lice and flux should take the hangman's part."

Without the leadership of Bacon, the rebellion soon fell apart. John Ingram took control of the rebellion, but he retained few followers. After a series of attacks by Berkeley and his troops, the small remaining pockets of Bacon's insurgents were soon defeated.

After executing 23 men by hanging, including Drummond, who'd assumed control as colonial governor of Virginia, Berkeley returned to power. But after an investigative committee sent a report of the incident to King Charles II, Berkeley was recalled back to England and relieved of his governorship. Berkeley sailed to England in order to argue his side of the matter to King Charles II, but he died before he had a chance to see the king.

Although it's claimed that King Charles II commented that Berkeley "hanged more people in that naked country he [Charles] had done for the murder of my father," the legend seems to have arisen roughly 30 years after Bacon's Rebellion.

Hardening racial castes

After Bacon's Rebellion, more and more racial distinctions were drawn in the legal designations of servitude and enslavement.

In 1682, Virginia enacted a law that stated that all those "imported into this country either by sea or by land, whether Negroes, Moors [Muslim North Africans], mulattoes or Indians who and whose parentage and native countries are not Christian at the time of their first purchase by some Christian. . . and all Indians, which shall be sold by our neighbouring Indians, or any other trafficking with us for slaves." By 1705, the act was revised from specifically designating people who could be enslaved to stating who couldn't, "Turks and Moors." The Slave Act of 1705 also made it illegal for Black people or Indians to own Christian white servants. The language of the two acts "was simplified, but the substance was the same." By distinguishing between white servitude and non-white enslavement, the racial line was drawn in the law.

According to A People's History of the United States, by Howard Zinn, around the same time, another series of laws were passed "requiring masters to provide white servants" with corn, money, guns, and land. Simultaneously, both racial and class divides were deepened, most likely in an attempt to prevent the cooperation that had occurred during Bacon's Rebellion.

Virginia disenfranchised free Black people in 1723, and by 1750, the legal distinction between servant and slave was completely set, "relegating all slaves to the status of property."