The Disturbing History Of Gas Baths On The U.S.-Mexico Border

Before 1917, citizens of Juárez and El Paso could cross freely back and forth between Mexico and the United States. No one asked for identification across the Stanton Bridge and passports weren't needed. But after creating a disinfection campaign within El Paso, officials in the city turned their attention towards the border and enacted a policy of disinfection and fumigation that lasted almost half a century. Using a variety of vinegar, kerosene, gasoline, and DDT, border officials subjected people to a toxic disinfection processes under the guise of public health. During the 1920s, United States border officials were even using Zyklon B in a manner that was commended and later borrowed by the Germans during World War II.

Although the fumigation and disinfection techniques were protested from the moment they were created, the protests didn't have a lasting effect. For those who had to cross the border for work, the decision was made to submit to the procedures.

It's impossible to know how many people total were subjected to the disinfection procedures, but at one point, Texas border officials were inspecting over 5,000 people per day. And even though the gas baths were claimed to be in response to the threat of typhus, they continued long after the typhus scare had passed. This is the disturbing history of gas baths on the U.S.-Mexico border.

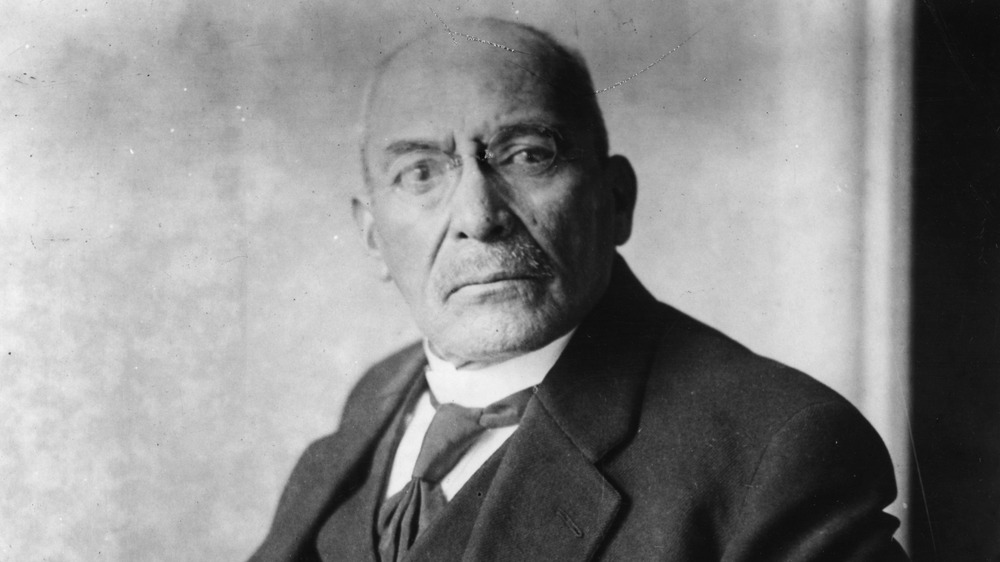

Election of Thomas Calloway Lea, Jr.

After being elected mayor of El Paso, Texas in 1915, Thomas Calloway Lea, Jr. immediately started a crusade against Mexican people under the guise of public health. Claiming that Mexican people were bringing typhus into the United States, Lea began sending telegrams to senators in Washington, D.C., demanding a center for quarantine near the border.

According to El Paso Politics, Lea's telegrams deplored the "dirty lousey (sic) destitute Mexicans arriving at El Paso daily [who] will undoubtedly bring and spread typhus unless a quarantine is placed at once." Even though local Public Health Service officials thought that the mayor's request was "extreme," Lea claimed in his telegrams that his requests were backed by the city's medical board.

The public health service official who was stationed in EL Paso, Dr. B. J. Lloyd, had another idea. While Lloyd didn't think that typhus was "a serious menace" and believed that quarantine wouldn't make much of a difference anyway, he suggested that he'd be happy to set up delousing areas to "bathe and disinfect all the dirty, lousy people who are coming into this country from Mexico."

Lea and the Mexican regime

Although Lea was incredibly racist, it seemed that at times his classism outweighed his racism. When Victoriano Huerta, the Mexican dictator who was deposed in 1914, found himself in an El Paso jail in 1915, Lea was his official attorney. Mayor Lea also prevented Huerta's bond from being higher and arranged Huerta's release. In a report to the Secretary of State, Collector of Customs Z. L. Cobb even noted that Lea's employment as Huerta's attorney "necessarily will affect the attitude of the El Paso authorities. Business sentiment here seems strongly with Huerta."

According to Ringside Seat to a Revolution by David Dorado Romo, Mayor Lea also viewed Mexican President Carranza favorably because he considered him to support "law and order." Pancho Villa, in comparison, was disparaged by the mayor because he represented the lower classes. After a raid by Villa on Columbus, New Mexico in March, 1916, Mayor Lea proclaimed that Villa was to be immediately arrested and tried if he ever entered El Paso. In response, Villa offered a bounty of "a thousand pesos in gold for the head of Mayor Lea."

After the Columbus raid, Villistas living in El Paso were given 24 hours to leave town. The same month, Lea passed an ordinance that prohibited "Mexican" newspapers in El Paso from publishing anything that could be considered "of a political nature." Mayor Lea also passed the first U.S. ordinance to outlaw marijuana due to his association of cannabis "with Mexican revolutionaries."

Sending inspectors to Chihuahuita

In March 1916, Mayor Lea sent city health inspectors to Chihuahuita, an area of El Paso where people of Mexican descent prominently lived. Since typhus can be spread by lice, according to Students Against Injustice and Dehumanization, the El Paso Herald reported that when lice was found, people were forced to take a "vinegar and kerosene bath, have their heads shaved, and their clothing burned."

Despite the fact that the El Paso County Medical Society published a report that said out of 5,000 rooms, only two cases of typhus were found in Chihuahuita, Mayor Lea was undeterred. According to Ringside Seat to a Revolution by David Dorado Romo, Lea sent demolition squads into Chihuahuita, and they destroyed hundreds of Mexican adobe homes. After snipers in Chihuahuita started firing at the demolition squads, the city health inspectors were ordered to carry rifles, and Lea's orders were "to shoot to kill." Even though the El Paso County Medical Society had stated in their report that "Chihuahuita is not the festering plague spot that it is pictured to be," hundreds of homes were destroyed and Mayor Lea worked on expanding his crusade.

According to the Zinn Education Project, the Anglo press greatly sensationalized the typhus threat, even though in 1917 there were "31 typhus cases in the U.S. and only three typhus related fatalities in El Paso."

El Holocausto

On February 27th, 1916, mandatory "delousing baths" were made into an official policy. Since a steam shower disinfection plant would take several more months to build, another method of delousing was proposed using a mixture of vinegar, gasoline, and kerosene.

On March 5th, 1916, less than a week later, 26 Mexican laborers were arrested and made to take a long dip in a tub that was filled to the top in the vinegar, gasoline, and kerosene mixture. Half an hour later, another prisoner named H.M. Cross was arrested for allegedly trafficking narcotics. Still presumably under the influence of a drug, Cross lit a match for his cigarette. Since the room was full of gasoline fumes, the entire jail caught fire in a horrible explosion.

According to Ringside Seat to a Revolution by David Dorado Romo, roughly 50 naked imprisoned people caught on fire. Ernesto Molina, the youngest prisoner at the age of 17, left "blood stained footprints" as he ran to jump out a window. The floors of the metal cells were so hot that they burned off the soles of the firemen who tried to put the fire out. A few people, like Daniel Urias and Diego Aceves, were able to survive, but at least 26 Mexican prisoners and two Americans burned to death, and another 25-30 prisoners suffered severe injuries and burns. In the Mexican community, the incident was referred to as El Holocausto, or "the Jail Holocaust," for many years afterwards.

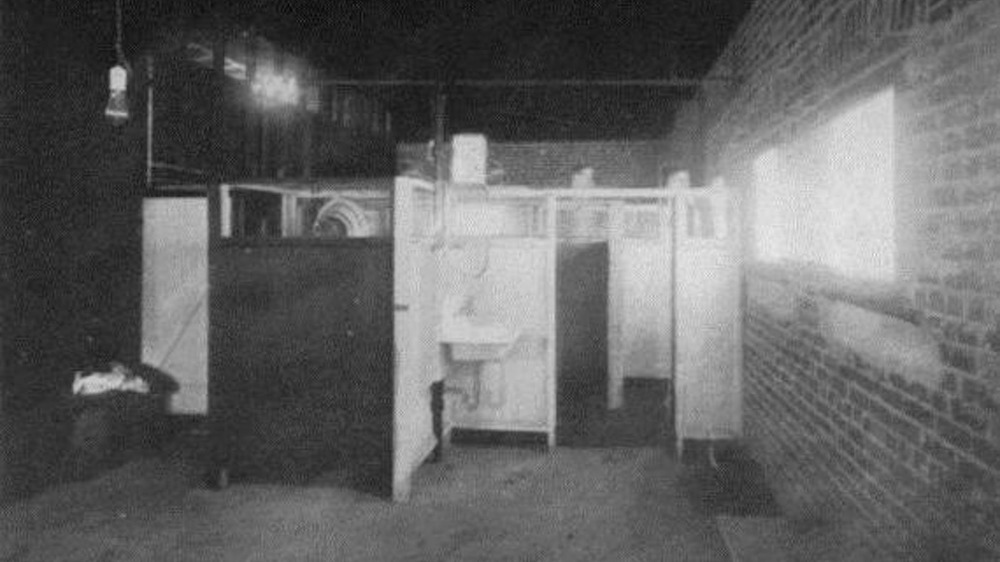

'Baths' at the fumigation facility

By 1917, the federal fumigation facility had been built by the Santa Fe bridge, and on January 27th, 1917, a notice was printed in newspapers stating that any Mexican citizen who wanted to enter El Paso had to have a card that confirmed having taken "a bath" at the fumigation facility. Children under the age of 10 weren't given their own certificates and were mentioned on their parents' certificates, but they were also required to go through delousing.

According to Public Health Reports from 1918, "All persons coming to El Paso from Mexico, considered as likely to be vermin infested, are sent through this plant for disinfection." The disinfection incorporated a mixture of insecticide, gasoline, and various other chemicals, and their clothes were fumigated with hydrocyanic acid. Sometimes, peoples' shoes even melted as a result of the dryer used by border officials.

In the first six months of the policy, over 850,000 people of Mexican descent were subjected to inspections. According to Ringside Seat to a Revolution by David Dorado Romo, border officials subjected Mexican people to delousing every eight days in order to be allowed into the United States, although initially people were subjected to the disinfection procedure every time they entered the United States.

Additional inspections

While their clothes were fumigated, people were forced to stand naked while a customs inspector checked their body hair for lice. Anyone who was found to have lice had all their hair shaved and were forced to take a bath in vinegar and kerosene. According to Militarizing the Border by Miguel Antonio Levario, rumors also started circulating that border officials were photographing women while they were nude.

In addition to delousing, Mexican people had to go through additional medical and mental examinations. People were checked for things such as conjunctivitis, clubbed fingers, asthma, bunions, and flat feet. Smallpox vaccines were also administered. People were also sometimes asked to put a puzzle together, solve additional problems, or write some sentences.

Border officials were also meant to be on the lookout for a variety of psychiatric conditions and anything from happiness to depression could keep someone from the United States. According to Regulations Governing the Medical Inspection of Aliens, "active or maniacal psychoses might be suggested by [...] smiling, facial expression of mirth, laughing, eroticism, boisterous conduct, meddling with the affairs of others, and uncommon activity." At the other end of the scale, sad faces, tearful eyes, and delayed responses could represent a "psychoses of a depressive nature."

The refusal of Carmelita Torres

The moment the federal fumigation facility opened, it was met with resistance. On January 28th, 1917, the first official day of the delousing policy, a streetcar was stopped crossing the Paso del Norte International Bridge and commuters were instructed to get off and go through the baths. Carmelita Torres, a 17-year-old who crossed the border regularly to work cleaning houses, refused to submit to a bath. Gathering the support of 30 other women on-board, they got off and marched back over to the Mexican side, where they proceeded to stop incoming streetcars and convinced other women who were domestic workers to join their protest.

According to Ringside Seat to a Revolution by David Dorado Romo, by 8:30 in the morning, over 200 Mexican women had blocked the traffic going into El Paso. By noon, the number was estimated to be several thousand. Many laid down in front of the streetcars to prevent them from moving. Others "took motor controllers from the conductors and hid them in their stockings once officers arrived to make arrests."

The demonstrators marched towards the delousing facility to encourage those who were still submitting to the process to resist. When border officials tried to disperse the demonstrators, the women threw rocks and bottles at the officials. One customs official was struck on the head. Several trolley conductors were also injured. General Murguía's death troops were called to the scene, but according to the El Paso Herald, "the soldiers were powerless."

Three days of revolt

While during the first day of protests men had mostly stood by and encouraged the women protestors from the sidelines, by the second day they joined the women protesting. But men weren't entirely absent during the first day. When José Marta Sánchez shouted "¡Viva Villa!" during the protests, he was promptly taken to the Juárez cemetery and murdered by Carranza's troops.

According to Mexico Unexplained, by the second day of the protests many had joined in order to protest the regime of President Carranza. At this point, households and businesses in El Paso could feel the effects of the protest through the lack of peoples' labor, so they asked the El Paso Chamber of Commerce to settle the issue. According to "The Bath Riots" by René Kladzyk, on January 30th, the Chamber of Commerce held an emergency meeting to discuss the gasoline baths that were occurring. But Dr. Claude C. Pierce, who had been sent from Washington to "design and oversee" the fumigation facility, repeatedly denied that kerosene was used and claimed that the baths were "merely soap and hot water baths."

On January 30th, several arrests were made on both sides and with soldiers prepared to meet protestors on the U.S. side, by the afternoon many people who needed to cross for work resigned themselves to the baths. Unfortunately, the decision wasn't complicated: "it was a requirement for anyone who wanted to work."

A weak compromise

After the riots were quelled, a compromise was reached between Mexican and United States authorities after several months of bargaining. While Mexican authorities thought that the disinfection process was too strict, American authorities claimed that it wasn't strict enough. According to When Germs Travel by Howard Markel, in a letter to the surgeon general, Dr. Pierce claimed that typhus was being brought to the United States by those who crossed the border at night "and have thus evaded disinfection and have spread the disease in El Paso and other places."

Although the disinfection was to continue, day workers only had to be subjected to it once a week if they had a valid certificate. However, these certificates were far and few between and sometimes United States border officials decided that someone needed a bath despite having a certificate.

Out of the 870,000 people examined between January and June of 1917, eight people were held for observation and 402 were excluded for illnesses. While the policy was relaxed when it came to more "well-dressed" or affluent Mexican people, disinfections remained in effect well into the 1960s.

Passing of the Immigration Act of 1917

Unfortunately, the riots had little lasting effect. Although President Woodrow Wilson had vetoed the Immigration Act twice in 1915, Congress overturned his veto and passed Immigration Act of 1917 on February 5th, 1917. The act barred immigration from Asia-Pacific countries, and required that all immigrants entering the United States, among other things, pay a head tax, take a literacy test, and have a passport.

According to Mexico by Don M. Coerver, Suzanne B. Pasztor, and Robert Buffington, the literacy test, "$8 head tax" that the act imposed, and the prohibition of immigration for contract labor directly affected Mexican workers. Businesses in the southwest were soon pressuring the government to exempt Mexican workers from the provisions, and as the United States' entry into World War I brought up the potential for labor shortages, the government acquiesced. According to the "United States Immigration Policy Toward Mexico" by Gilberto Cardenas, this set two significant precedents of relaxing laws "when it became desirable to import Mexican workers" and invoking the restrictive provisions "when it was deemed necessary to exclude Mexicans from immigrating on a permanent basis." Before the Immigration Act of 1917, "Mexicans were legal." The exemptions lasted until 1921, but the border was never the same again after 1917.

Adolf Hitler even praised the United States' Immigration Act of 1924, noting that, "The American Union categorically refuses the immigration of physically unhealthy elements, and simply excludes the immigration of certain races."

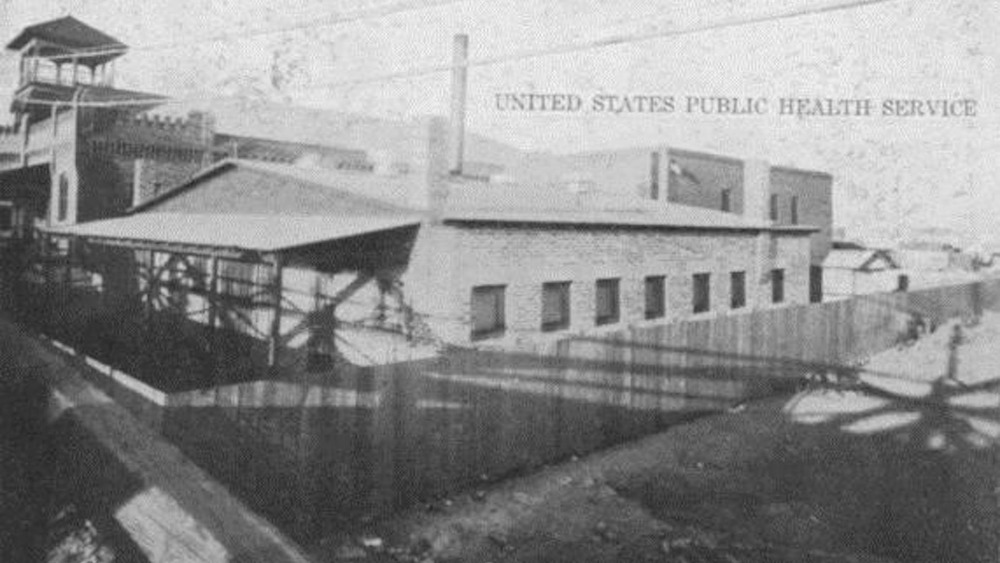

Use of Zyklon B

In the 1920s, the United States started using Zyklon B for clothing fumigation. According to NPR, the building where the fumigation was carried out was even called the "gas chambers."

These American gas chambers were a partial influence for the German gas chambers that were later used in World War II, the other influence coming from the Soviet gas vans. In 1938, Dr. Gerhard Peters published an article in a German scientific journal "specifically praised the El Paso method of fumigating Mexican immigrants with Zyklon B." Dr. Peters later went on to become the managing director of Degesch, which was one of two German firms that started mass-producing Zyklon B in 1940.

According to "The Bath Riots" by René Kladzyk, in 1942, DDT powder dusting replaced kerosene and vinegar showers. Tragically, since DDT is a pesticide, it was found to have "detrimental health consequences including cancer, infertility, miscarriage, as well as nervous system and liver damage." Unfortunately, there have also been no major studies in regard to the long-term health consequences for Mexican people who had to endure routine exposure to such chemicals.

Fumigation into the 60s

Disinfection and fumigation were practiced as late as 1963 and was in place during the Bracero Program from 1942-1964, during which over two million Mexican workers came to the United States for short-term labor contracts.

According to Ringside Seat to a Revolution by David Dorado Romo, immigration agents made Mexican workers strip and then proceeded to spray their entire bodies with insecticide. Some would vomit due to the terrible smell of the chemical sprays and workers such as Raul Delgado remembers how "the agent would laugh at the grimacing faces we would make. He had a gas mask on, but we didn't." Sometimes, people were even subjected to disinfection multiple times. Medical exams also continued during the Bracero Program, ranging from chest X-rays to examinations for hemorrhoids.

At the end of the day, according to "Borders and Bodies" by Eve Galanis, spraying immigrants and laborers with toxic chemicals "had very little to do with typhus, and more to do with physically and psychologically controlling the flow of migrant workers."