How The Plan Of San Diego Changed America Drastically

Although the Plan of San Diego didn't itself come to fruition, its consequences and history reverberate over 100 years later. The Plan of San Diego brought to the forefront a mobilized Mexican community that resisted the status quo, represented political motivations playing out from macro to micro scales, and resulted in increased stigmatization and violence against people of Mexican descent along the border.

The Plan of San Diego called for a takeover of the states along the Mexican border and a proposed alliance between people of Mexican descent, Black people, and Native people. While the most-often talked about part of the Plan is its proposal to kill white men over the age of 16, the uncertain authorship of the Plan reveals the potential for a plot that was more interested in inflaming than executing.

From 1910 to 1920, there were countless slaughters of Tejanos and Mexicans by local law enforcement and civilians, escalating after the discovery of the Plan of San Diego in 1915. People of Mexican descent were second only to Black people when it came to suffering at the hands of lynch mobs. But the white public had little interest unless a white American was killed or a raid was reported. As a result, it's impossible to know how many people were killed in the vigilante violence that followed the discovery of the Plan of San Diego, although estimates are as high as 5,000. This is how the Plan of San Diego changed America drastically.

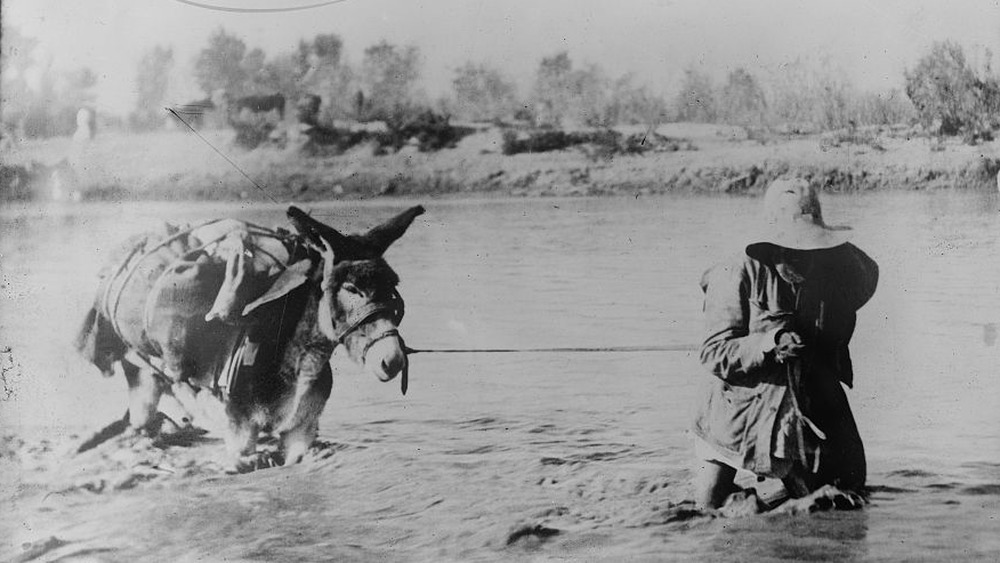

Tejanos in 1910

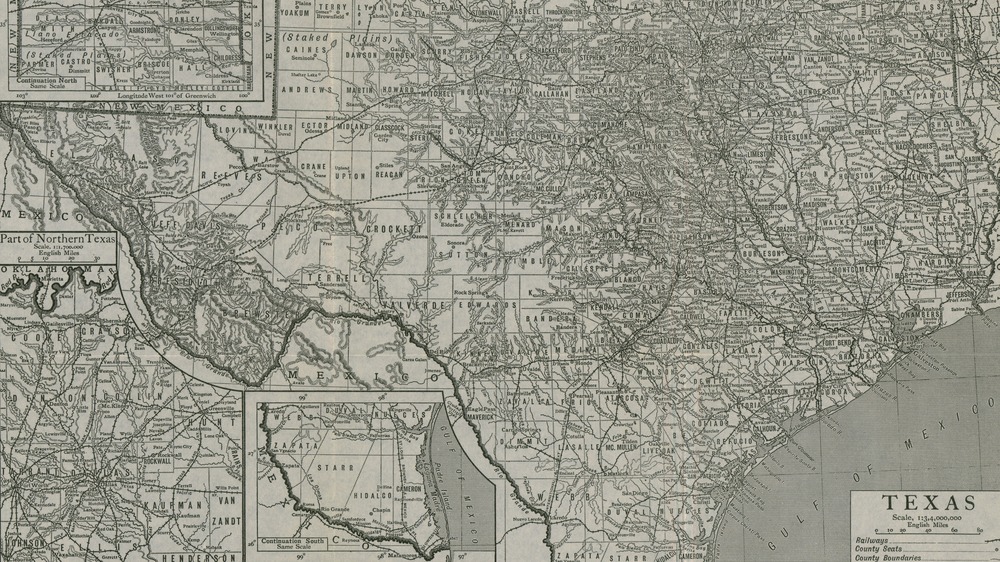

By the turn of the 20th century, people of Mexican descent in Texas, or Tejanos, numbered at most five percent of the state's population. In towns along the border, there were enclaves where Tejanos were the majority of the population, per Refusing to Forget. As roads and railroads allowed greater mobility, white Americans moved to border towns in larger numbers.

Simultaneously, the Mexican Revolution led to an increased number of people immigrating to the United States from Mexico, either fleeing political persecution during regime changes or as war refugees. According to LatinxKC, in 1910, roughly 20,000 Mexican people entered the United States every year and by 1920, that number had risen to between 50,000 and 100,000 per year.

According to Refusing to Forget, this discrepancy in demographics was viewed with unease by white Americans. In 1914, Texas Governor Oscar B. Colquitt received a letter from the white citizens of Val Verde County, requesting, and receiving, Texas Rangers and permission to create civilian home guards "because no one can tell just what stand the Mexican residents [in Texas] might take against the whites," according to Border Policing: A History of Enforcement and Evasion in North America.

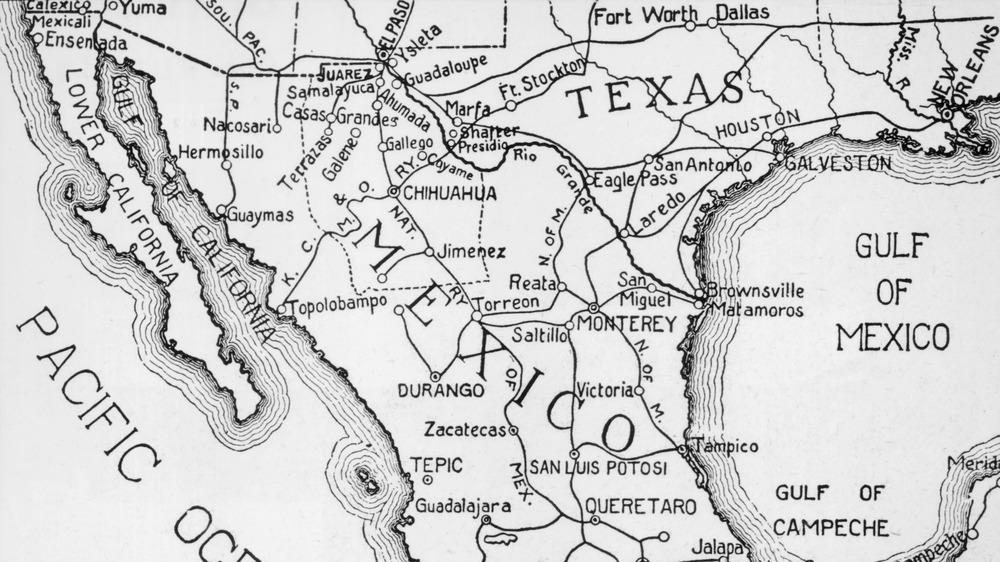

The Mexican Civil War and America's influence

In 1910, a revolt against the regime of Porfirio Díaz Mori resulted in his resignation in 1911 and for another nine years, the country would be gripped by revolution and civil war. Although Francisco Madero was successful in the 1911 elections, he was assassinated in 1913 after General Victoriano Huerta conspired to betray Madero. After Madero's assassination, Huerta promptly established a military dictatorship.

According to The History of Mexico: From Pre-Conquest to Present by Philip Russell, United States Ambassador to Mexico Henry Lane Wilson actively assisted in the orchestration of the coup, and was one of the few to publicly "accept the [Huerta] Government's version of the affair and consider it a closed incident."

Huerta quickly sought to get the Taft administration on his side and for a moment it seemed as though the United States would support Huerta. But within two weeks of the coup, Woodrow Wilson was inaugurated as president, and realizing the extent of Ambassador Wilson's role in the coup, he dismissed Ambassador Wilson and refused to recognize the Huerta regime, per Britannica.

As Huerta's regime was overthrown, various groups wrestled for control over Mexico. Venustiano Carranza and his constitutionalist faction wanted to restore Mexico to Madero's moderate and liberal rule, while Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata's revolutionary factions fought for radical land reform.

The controversial Plan of San Diego document

On January 6th, 1915, a document was signed by nine people in a jail cell in Monterrey, Mexico. Titled "The Plan of San Diego," the 15-point manifesto outlined an insurrection towards "proclaiming the liberty of the individuals of the black race and its independence of Yankee tyranny." Calling for a union of Native people, Black people, and people of Mexican descent, the points included freeing various states along the Mexican border towards the creation of an independent republic, a potential annexation to the government of Mexico, as well as the execution of all white American men over the age of 16.

The date of the insurrection was set at February 20th, 1915, at two in the morning. While the plan was named after San Diego in Duval County for where it was "ostensibly written," the plan was meant to be executed across various states along the southern border.

According to The Plan of San Diego: Tejano Rebellion, Mexican Intrigue by Charles Harris and Louis R. Sadler, the plan is inflammatory but also exceptionally scattered. Other than the Apache people, the other Native tribes in the area are reduced to a monolith. After helping Black people achieve independence, another independent state would be made for them. And despite showing little concern for people of Asian descent, point twelve includes people of Japanese descent, including that "nor shall any leader enroll in his ranks any stranger, unless said strange belong to the Latin, the Negro, or the Japanese race."

Who authored the Plan of San Diego?

Although it's known who signed the Plan of San Diego, the true authorship of the document has never been concretely established. While the nine people who signed it claimed that they were Huertista, followers of Huerta, Basilio Ramos Jr. admitted that the document had been prepared by a friend and "brought into the jail by the servants who delivered the meals."

According to the Hispanic American Historical Review, there are numerous hypotheses into the original authorship and intent of the plan. On one extreme, it's been suggested that the architect of the plan was W. M. Hanson, a future Senior Captain and Inspector of the Texas Rangers, in an attempt to cause trouble for the Carranza government. At the other extreme, it's possible that the Plan was as much of a liberation movement created by Mexican-Americans as it claimed to be. But recent scholarship suggests that the Carranza government was the main sponsor of the plan.

By 1914, Huerta had been driven into exile, and the fighting was concentrated between the Constitutionalists and the Villistas and Zapatistas. And while Carranza had declared himself de facto president, he knew that recognition from the United States could cement his power. So under the guise of the Plan of San Diego, Carranza reportedly precipitated numerous raids until the United States recognized him as provisional President of Mexico.

Arrests and indictments for the Plan of San Diego

The Plan was discovered on January 23rd, 1915, when Basilio Ramos Jr. was arrested while trying to garner support for the manifesto. A copy was found on Ramos, signed by him and eight other individuals. Handed over to the Bureau of Investigation, Ramos and the other signatories were charged with conspiracy to commit treason, but since Ramos was the only one who had been arrested, he was the only one arraigned on January 29th.

According to the Hispanic American Historical Review, Ramos admitted to signing the Plan and was held on a $5,000 bond. On February 10th, Manuel Flores and Antonio González were also arrested, but there was no way to connect the men with the conspiracy and they were both shortly released.

On May 13th, 1915, a federal grand jury in Brownsville indicted Ramos and eight others with conspiracy "to steal certain property of the United States of America," while simultaneously lowering Ramos' bond from $5,000 to $100, which gives the impression that they didn't really believe that the Plan was in danger of succeeding. Ramos was able to raise the $100 and after posting bail, he fled back to Mexico.

While authorities had hoped to keep the discovery of the Plan under wraps until they determined whether or not there was a real threat, on February 2nd, the Associated Press broke the story of the Plan of San Diego and soon the story was all over Texas, according to Harris and Sadler.

Local reactions to the Plan of San Diego

While it's not clear how many total individuals participated in the subsequent raids on Anglo farms, Tejanos were supportive of the uprising and even offered shelter to fighters. In comparison, according to Black Past, Black people in Texas didn't seem to take the Plan seriously.

Whether or not the raids were orchestrated as a part of the Plan of San Diego, Anglo militias immediately organized in response. And according to Revolution in Texas by Benjamin Heber Johnson, regardless of what side Tejanos were on, they "watched the racial lines harden as the violence continued and Anglos armed themselves."

Tejanos in San Benito were forced to give up their firearms and according to Refusing to Forget, it was considered by some to be "open season [on] any Mexican caught in the open armed or without verifiable excuse for his activities." In response to the disarmament and vigilante killings, thousands of Tejanos fled into Mexico. Thousands more who tried to stay were either murdered or expelled by the Texas Rangers.

Weeks of raids after the Plan of San Diego's discovery

Throughout the summer, there were several of raids on Anglo ranches, some of which resulted in the deaths of ranchers. Before this, President Wilson had agreed to change federal policy so that following March 5th, raiders were considered "belligerents entering American territory for unlawful acts," so they weren't just violating private property, but they were "a foreign operative violating American sovereignty."

According to The Injustice Never Leaves You by Monica Muñoz Martinez, prominent ranches "had become a symbol of Anglo farm colonization" and were especially targeted by Sediciosos, or raiders. One such ranch was the King Ranch, between Corpus Christi and Brownsville, considered during its time to be "the greatest symbol of Anglo domination on the frontier." It was the first to develop a new cattle breed in the United States, as well as the first to use barbed-wire fencing. The ranch also housed a headquarters for the Texas Rangers, with whom they had such an intimate relationship that people called the Rangers "the King Ranch's private security."

The first (widely accepted) raid occurred on July 4th, 1915 and they persisted until mid-October. Bands of men also cut telegraph wires and mangled railroad lines. It's estimated that at least 30 total raids occurred from July 1915 to July 1916, resulting in the deaths of 21 white Americans.

According to Hispanic American Historical Review, despite Carranza officials denying any connection to the raids, almost all of the raids subsided after Carranza's presidency was recognized by Washington.

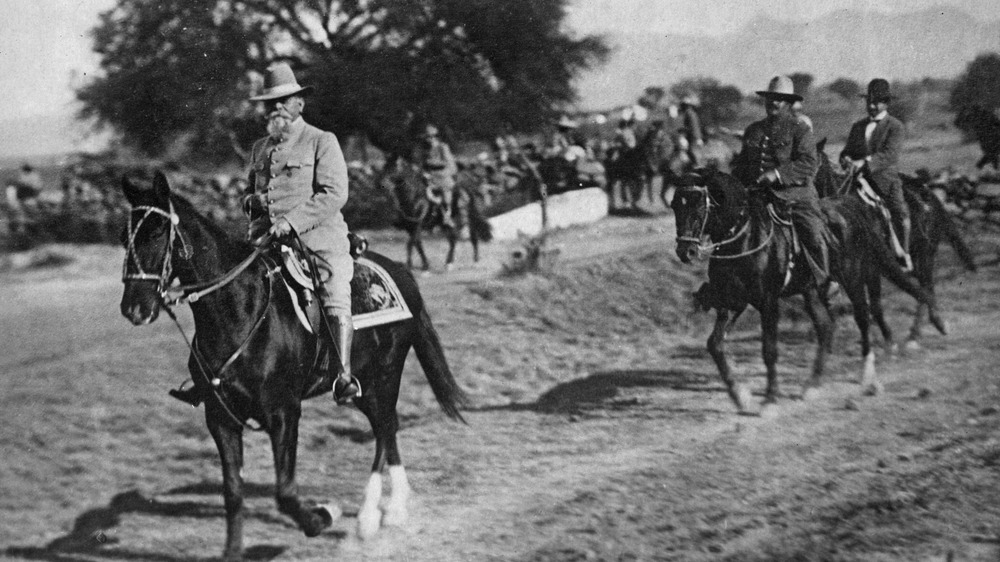

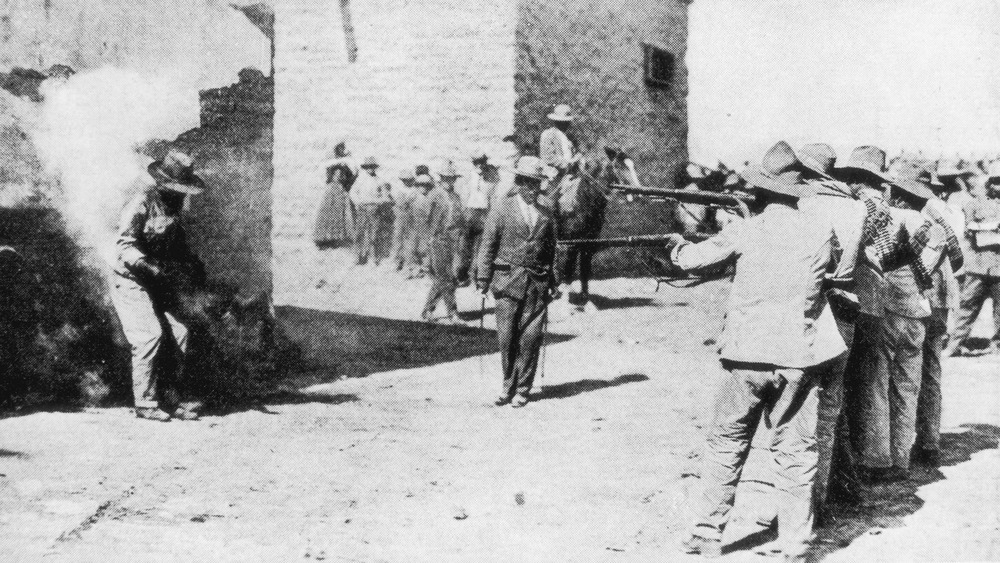

The hour of blood

In response to the Plan of San Diego, the state of Texas expanded its Ranger force and a wave of vigilante killings started by local officers, Texas Rangers, and civilians. Rangers killed people of Mexican descent indiscriminately, regardless of whether or not they were a Sediciosos, a Tejano, or a Mexican national. Lynchings also occurred after every major raid in 1915.

According to Revolution in Texas by Benjamin Heber Johnson, Tejanos who owned land were especially at risk of vigilante violence "regardless of whether they aided in the raids." Although federal records report that 300 people of Mexican descent were executed in the months after the discovery of the Plan of San Diego, numbers could be as high as 5,000. Rangers often also destroyed peoples' crops and burned their homes in the process.

Rangers often left dead bodies where they fell and people were too afraid to go bury them lest the Rangers shot them too. And tragically, all too frequently the Rangers would murder someone they hadn't necessarily intended to murder due to an "Anglo ineptitude with Spanish surnames and enthusiasm for killing on the flimsiest of evidence," per Johnson.

Along the border, this period was referred to as Hora de Sangre, or the Hour of Blood. According to PBS, none of the murders were ever properly investigated.

Ideological divides after the Plan of San Diego

Many Tejanos felt themselves growing more and more divided as white Americans unified in hatred. Despite being supportive of the uprisings, countless people were caught in the crossfires and fell victim to the indiscriminate vengeance of the Texas Rangers.

According to Revolution in Texas, while many Tejanos joined the uprising out of fury at the murder and dispossession, others who found themselves targeted by the rebels chose to name suspects and expose them to vigilante violence. Other Tejanos continued to work "loyally for the machine in positions such as deputy sheriff and thus numbered among both the Sediciosos' victims and pursuers."

Others who detested the rising rate of murders and vigilantism still wanted nothing to do "with any violent upheaval or radical overthrow of established economic power." They considered the attacks on farmers and railroads by Sediciosos as attacks on economic development, and they offered little support to the Sediciosos.

But regardless of one's ideological convictions, anyone of Mexican descent lost their right to due process. "Local whites called this process 'evaporation.' México Texanos and Mexicanos labeled these killings the matanza (massacre)," Trinidad Gonzales notes.

The government notices the Rangers' conduct

As murders by Texas Rangers increased, the United States government slowly began to notice. According to Refusing To Forget, United States military officers who'd been mobilized and deployed to the border were apparently alarmed at the conduct of law enforcement and Texas Rangers.

On October 30th, 1915, the United States Secretary of State Robert Lansing even sent a telegram to Texas governor James Ferguson, asking him to discreetly have a word with "state and county officials" towards "allaying race prejudice and in restraining indiscreet conduct."

Some white Texans tried to assist Tejanos in their fight for justice, but they suffered similar consequences. In 1916, after José Morin and Victoriano Ponce disappeared after being taken into custody, Thomas Hook of Kingsville, Texas helped locals write a telegram to President Wilson "asking for federal intervention to safeguard their rights." Shortly after, Hook was pistol-whipped in a courthouse hallway by Texas Ranger Captain J.J. Saunders, in whose custody Morin and Ponce had disappeared.

The government finally investigated in 1919, when José Tomás Canales, a state representative from Brownsville, spearheaded an investigation. According to Latina, Canales, the only Tejano in the state's legislature, filed 19 charges against the Texas Rangers, demanding an investigation into their conduct.

While the investigation revealed hundreds of atrocities, the committee absolved the Rangers of any wrongdoing, commending them instead despite "gross violation of both civil and criminal laws" by some. The witness testimonies were so "explosive," transcripts weren't published until the 1970s.

Carranza's plot succeeds

While Carranza officials repeatedly denied involvement in the raids, in August 1915, official Carranza newspapers began a propaganda campaign in support of the supposed "Texas Revolution." And according to the Hispanic American Historical Review, at least one Mexican officer was in Texas "observing, if not advising and participating in, the raids." At one moment, it was even directly implied to Washington that if the Carranza government were recognized, then the raids would cease.

After several raids in September, the United States government once more demanded that the raids stop and this time, the Carranza regime obliged. There was a lull in the raids until October 18th, when a passenger train was attacked and looted in the night five miles north of Brownsville, leaving three people dead. And on October 19th, the United States recognized Carranza as provisional President of Mexico.

Within a week, the number of raids subsided. Although there was a "final flurry of raids," it's unclear whether or not these were directed by the Carranza regime. Regardless, without the support the Carranza regime had once provided, some Sediciosos activity subsided. While Pancho Villa led an attack in 1916 in retribution for America's recognition of Carranza, the attack was in Columbus, New Mexico rather than Texas.

Lingering consequences after the Plan of San Diego

While Carranza's plan was ultimately successful towards his own personal gain, the massacre it instigated against Tejanos and Mexicans has lingering repercussions to this day. While antagonisms didn't begin with the Plan of San Diego or its resulting consequences, this period of violence set the stage for the continued dehumanization of people of Mexican descent by the United States government. According to Refusing to Forget, the Texas Rangers were also instrumental in voter suppression, such as the 1918 election, when Mexican votes dropped over 70% from the primary. Harassment and violence at the hands of law enforcement also continues to this day.

Although the Texas Rangers had the size of their force cut, soon many Rangers were joining the newly formed Border Patrol. Established in 1924, Border Patrol followed much of the policy and tradition established by local law enforcement. According to PBS, in the late 1920s, several former rangers were turned into Border Patrol officers.

And the rhetoric of "banditry" in regards to people of Mexican descent that was popularized during this period is equally prevalent 100 years later, demonstrative in President Donald Trump's repeated derogatory remarks about people of Mexican descent.