The Tragic History Of Jerusalem Explained

Jerusalem is one of the holiest cities in the world, playing a crucial role in the three Abrahamic religions — Judaism, Christianity, and Islam — and serving as the home of some of the most significant shrines, temples, churches, and other locations for all three. As the capital city of a land square in the middle of countries that would develop into some of the greatest empires known to history, Jerusalem has been something of a political football, passing hands from one empire to the next. It has been captured and recaptured over 20 times, with quite a few events that can be named "the Siege of Jerusalem."

Despite being a city famous for holy men such as King David, Jesus, and Muhammad, it has been a site of terrible violence and great tragedy in its millennia-long history. Here is a brief outline of just some of the greatest catastrophes to befall the Holy City.

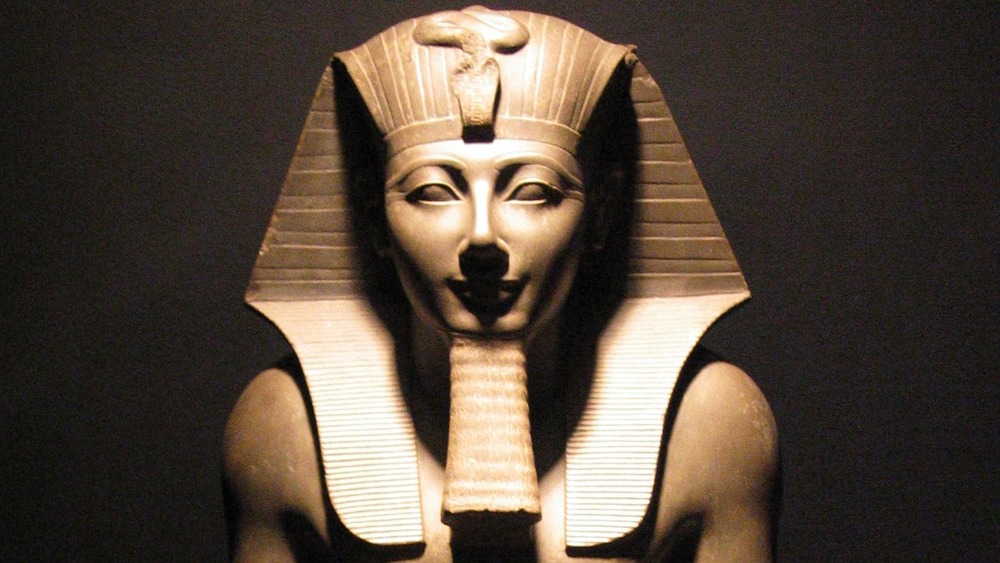

Pre-Israelite Jerusalem was under Egyptian control

According to the Ancient History Encyclopedia, no one is sure exactly where the name "Jerusalem" came from. Most argue that it comes from a Sumerian word meaning "to lay a foundation," though some argue it comes from the name "Shalem," the Canaanite god of dusk. Alternatively, it could share a linguistic root with the Hebrew word shalom or the Arabic word salam, meaning "peace." This last explanation has something of an ironic ring to it, as the city of Jerusalem has barely known a moment's peace in its long history. Among the earliest people to live in the area now known as Jerusalem were the Canaanites, a late Bronze Age group who are thought to have developed into the Israelites through the evolution of their polytheistic religion into a more YHWH-centric one.

The Bible tells that the patriarch of the Israelites, Abraham, came from Canaan before his descendants ended up in slavery in Egypt. However, archaeologists argue that there is no evidence that any such exodus ever happened, nor is there any sign of an Israelite captivity at this time. What does exist, however, is evidence that Jerusalem was the capital of an Egyptian vassal state under the New Kingdom of Egypt led by Thutmose III. Jerusalem eventually escaped Egyptian control, but its independence over the centuries would be spotty at best.

Jerusalem's greatest glory might not have even happened

The Bible tells us that after Moses led the Israelites from Egypt to the Promised Land of Canaan and Joshua led them in conquest over the peoples there, the land was without rulers, with only occasional military leaders called "judges" — such as Samson or Gideon — providing leadership during this period. As a result, the Israelite people asked God for a king, which he provided in the form of the not-so-great King Saul, followed by the glorious reigns of King David and his son Solomon. These three kings ruled over a United Monarchy of the kingdoms of Israel and Judah that stretched from the Mediterranean Sea to the Jordan River. The biblical story goes on to say that Solomon's 40-year reign saw not only the construction of the Temple in Jerusalem but also an accumulation of wealth and splendor that rivaled the great emperors of the East. Solomon's son Rehoboam couldn't maintain so great a kingdom, however, and the United Monarchy was split into the Northern Kingdom of Israel and the Southern Kingdom of Judah.

According to Haaretz, however, the United Monarchy might not have ever existed. There is no archeological evidence to support the level of wealth and grandeur described in the biblical account, and only the most bare-bones evidence suggests that David and Solomon even existed at all. Accounts of Israel's greatest age were likely written centuries later to support then-contemporary royal ideology.

Jerusalem escaped the Assyrians by the skin of its teeth

Only a few generations after the death of Solomon, the king who — according to the Bible — raised the Kingdom of Israel to its highest heights, a long string of corrupt and ineffective kings of Israel and Judah had left the two states as tiny kingdoms sandwiched between much bigger powers, including the Egyptians to the west and the notoriously aggressive Assyrians to the east. As the Jewish Virtual Library explains, the small size of the two Hebrew kingdoms was a big problem for the Israelites and Judahites. In 722 BCE, the Assyrians, the dominant empire in the region at the time, conquered the northern kingdom, capturing its capital city Samaria and driving its people into exile. The northern tribes were then scattered throughout the Assyrian Empire, becoming what are known as the "ten lost tribes of Israel."

The southern capital, Jerusalem, narrowly escaped the same fate. The Assyrian king also besieged Jerusalem following the fall of Samaria but failed, and no one is quite sure why. The Judahite king, Hezekiah, tried to bribe the Assyrian king, but although he took the money, he did not cease his siege. According to the Bible, the Assyrian threat was ended when God sent an angel that killed 185,000 Assyrian soldiers overnight. This, uh, probably didn't happen, but it is possible that the onset of a plague on the Assyrian army serendipitously saved Jerusalem.

Jerusalem was destroyed (for the first time)

Although the Kingdom of Judah escaped the fate of the northern kingdom when the Assyrians came through, they weren't so lucky when the next big, bad empire came to town. One of the greatest disasters in Jewish history came in 587 BCE, when Nebuchadnezzar, king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, laid waste to the city of Jerusalem, destroyed Solomon's temple, and drove the people of Judah into exile.

According to the Encyclopedia Britannica, the first Babylonian siege of Jerusalem happened a decade earlier and saw the Judahite king Jehoiachin removed from the throne and replaced with a puppet monarch controlled by the Babylonians, Jehoiachin's uncle Zedekiah. However, after Zedekiah revolted against the Babylonians with the help of the Egyptians, Nebuchadnezzar returned and razed the city after a months-long siege in which the people of Jerusalem suffered greatly from starvation and thirst, as described in the Book of Lamentations.

Once the city and the temple were destroyed, most of the Jews in Palestine were forcibly deported to Babylon, where they were detained for about 50 to 70 years, depending on the source. According to the prophet Jeremiah, only a few of the poorest people of Jerusalem were left in the city to tend to the land. The Jewish citizens who remained in Babylon after the exile formed the first permanent communities of what would become known as the Jewish Diaspora.

Jerusalem was restored by Cyrus the Great

Empires don't last forever, and there's always a more powerful one around the corner ready to jump in when the current power shows weakness. Just as the Assyrians had been eclipsed by the Babylonians, so, too, would the Babylonians fall to the greatest conqueror the world had yet seen at that time: Cyrus the Great, leader of the Persian Empire. As the Jewish Virtual Library explains, Cyrus was a Zoroastrian, meaning he believed that the universe was dualistic, divided into good and evil. He felt that, through a conquest of the entire known world, he could personally hasten the triumph of the good under the command of Persia. Believing as he did that all gods were either intrinsically good or bad, Cyrus felt that the worshipers of YHWH, who he viewed as one of the good gods, should be free to worship their deity that supported his goal of net cosmic good.

As such, when Cyrus conquered Mesopotamia, he freed the exiled Jews and sent them back to Judah to rebuild the temple. Between 538 and 518 BCE, the returned Judahites built a second temple on the ruins of Solomon's temple, despite the fact that so many deported Jews had elected to stay in Babylon. The Second Temple period saw Judah re-established specifically as a theological state, with a new style of Judaism heavily influenced by Zoroastrianism.

The Greeks desecrated the Temple

The Persian Empire met its end at the hands of someone called Alexander the something in 330 BCE, and as a result, Judah and its capital Jerusalem fell under Macedonian control. The problem is, this guy Alexander didn't live too long after that, leaving his immense empire that ranged from Greece to Central Asia under the command of a bunch of generals who couldn't decide who should be in charge. As the Ancient History Encyclopedia explains, Judah, although originally controlled by the Ptolemaic dynasty out of Egypt, fell under the control of the Seleucid Empire around 200 BCE during the reign of the Seleucid emperor Antiochus III.

Part of Alexander's goal of conquest had been to spread Greek culture around the world, and his successors attempted to continue that path, Hellenizing the lands under their control. The efforts to Hellenize Jerusalem came to a climax during the reign of Antiochus IV Epiphanes when he profaned the Temple in Jerusalem to establish it as a place to worship him, the emperor. This led to a revolt against the Seleucids led by Judah Maccabee and his brothers, who recaptured the Temple and rededicated it to the worship of YHWH. (This is what Hanukkah is about.) The successful revolt led to the establishment of a new Judean kingdom led by the Hasmonean dynasty established by Judah Maccabee's brother Simon.

Jerusalem was destroyed (for the second time)

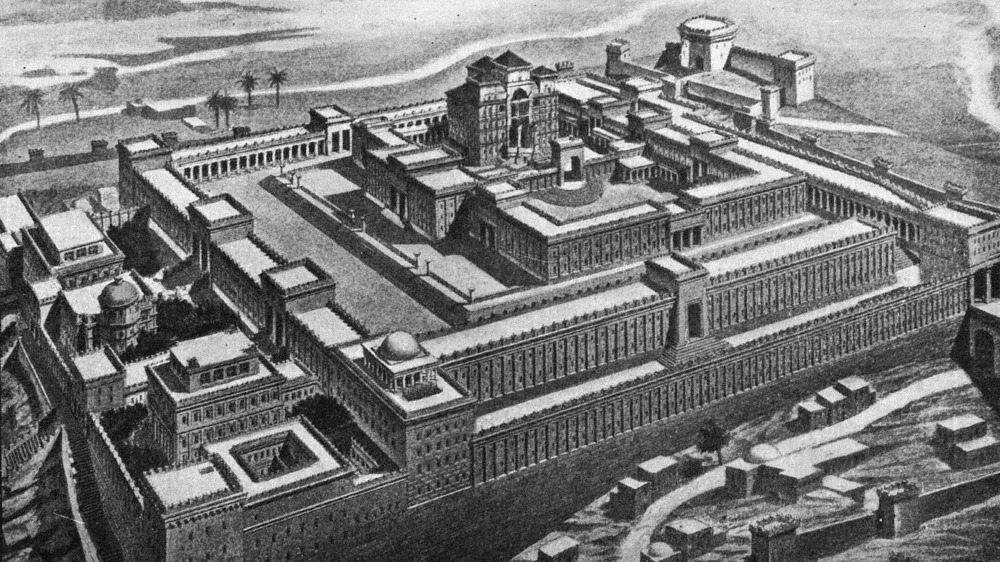

The Jews were able to enjoy about 100 years of relative autonomy during the Hasmonean kingdom, but as you can probably guess, it wasn't meant to last. The Greek empires that came in the wake of Alexander were eclipsed by the hot new thing in the Mediterranean, the Romans. As the Jewish Virtual Library explains, by 37 BCE, the Hasmoneans had been entirely removed from power and replaced by Herod the Great, a Jewish client king of the Romans. The Herodians ruled for a few years, leading massive construction projects in Jerusalem, including remodeling the Temple. However, by 6 CE, Judah (called Judea by the Romans) fell under direct Roman control, which the Judeans — who had already led a few insurrections against the Roman powers — did not care for at all.

Roman attempts to suppress Jewish lifestyle exceeded even those of Antiochus IV and led to multiple full-scale revolts by the Judeans. These revolts were finally put down by the Roman emperor Titus, who, in 70 CE, led his victorious troops in burning Jerusalem — and the Second Temple — to the ground. Hundreds of thousands of Jews were killed or sold into slavery as a result of this siege, and after one last revolt in 132 CE, Jerusalem was fully plowed up and renamed Aelia Capitolina. Judea got a new name as well: Palestine.

From the Romans to the Persians to the Romans to the Arabs

After the destruction of Jerusalem by the Romans, it was rebuilt as a typical Roman city known as Aelia Capitolina. Jews were not allowed into the city at all — a rule enforced by capital punishment — except on the Jewish holiday of Tisha B'Av, a day of mourning for the destruction of the Temple, among other catastrophes. However, as Enjoy Jerusalem explains, after Christianity was adopted as the official religion of the Roman Empire in 324 CE, the emperor Constantine and his successors ordered the construction of Christian holy sites, such as the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, throughout the city. During the Byzantine period, Jerusalem, still called Aelia, became one of the five key cities for Christianity, along with Rome, Constantinople, Antioch, and Alexandria. For the next three centuries, Jerusalem enjoyed relative stability under the Byzantines. You can probably guess, however, that this was not to last.

In the early seventh century, Jerusalem passed hands from the Byzantines to the Persians and back before being besieged again in 636 CE by Arab Muslims. Jerusalem was (and is) one of the holiest cities in Islam, and the conquering Arabs brought in substantial construction projects to Islamicize the city. Most notably, they built the Dome of the Rock and the Al-Aqsa Mosque, the third holiest site in all of Islam, both on the site of the destroyed Jewish Temple. Jerusalem enjoyed another period of relative, temporary stability under the Umayyad caliphate.

Crusaders and Muslims vied for control of Jerusalem

At the end of the 11th century, the Christian Byzantine Empire was losing more and more ground to encroaching Seljuk Turks, and despite ongoing tensions between the Eastern and Western churches, the Byzantine emperor asked the pope for help against the Muslim invaders. In 1095, the pope sent a host of European Christians to aid the Byzantines and, you know, while they were there, liberate the Holy City of Jerusalem from Muslim hands. As History explains, this was the beginning of the series of campaigns known as the Crusades. After joining forces somewhat tenuously with Byzantine leaders, the Crusaders marched on Jerusalem in 1099, when the city was under the control of the Fatimid dynasty out of Egypt, the enemies of the Seljuks.

After a month-long siege, the Crusaders successfully ousted the Fatimid Caliphate from Jerusalem, slaughtering almost of the Muslim and Jewish inhabitants of the city. The invading Europeans established four large Crusader states, including the Kingdom of Jerusalem, which was filled with Christian immigrants to block the return of Muslims and Jews. In 1187, the Muslim general Saladin led a campaign against the Christian Kingdom of Jerusalem and retook the city for Muslims and Jews, expelling Western Christians. In 1229, the Sixth Crusade saw the peaceful transfer of Jerusalem back into Christian control, but this peace was short-lived, and Muslims soon retook the city.

Jerusalem thrived and then declined under the Ottomans

As the Crusades ended, Jerusalem and much of the Middle East fell under the control of a dynasty known as the Mamluks and remained so until 1517, at which point the Ottoman Turks emerged as the dominant power in the region for the next four centuries. As Jewish Virtual Library explains, Jerusalem enjoyed a period of renewal under the reign of the Ottoman emperor Suleyman the Magnificent, who brought efficient governance and infrastructural improvements that increased immigration into the city by returning Jews. Jerusalem flourished as a city of both religious freedom and intellectual enlightenment. However, this was not to last, and the overall quality of rule by the Ottomans declined over time. By the late 18th century, the city had stagnated economically and become something of a backwater. Land owned by absentee landlords and worked by poverty-stricken farmers was stripped of natural resources.

The 19th century saw some progress within the city as Western powers began showing interest in Jerusalem again, often through the work of missionary groups and archeological studies based on biblical history. This led to much modernization, such as railroads, telegraphs, and a postal service, but the influx of populations of different ethnicities and religions inspired among some Israelite Jews the nationalist spirit of Zionism, which has led to many modern conflicts in the region, as they sought to reassert Jewish sovereignty in the land.

British rule of Jerusalem was mandatory

The Ottoman Empire met its end in the aftermath of World War I, and following the 1917 Battle of Jerusalem, the Holy City once again changed hands, the time to the British Army. As Time explains, a mandate drawn up in 1920 placed Jerusalem and its surrounding areas under the control of the British Empire, giving the area the truly amazing name of Mandatory Palestine. During this period, even more Jews who had migrated to Europe began flowing back into Palestine while it was under European control, only adding fuel to the simmering unrest that had developed during the Ottoman Empire's declining years. The ever-increasing Jewish population who saw Palestine as theirs by right fueled tensions with Arab nationalist movements developing at the time.

According to the Jewish Virtual Library, it was in the 1920s that Arab nationalist groups began using suicide bombings as a means by which to terrorize Jewish immigrants, hoping to push them back out of Palestine. The decade also saw a series of riots by Arab groups, most notably in 1920 and 1929. Some of these violent acts were, in fact, instigated by the British, who were hoping to eliminate the Zionist movement in Palestine. With British encouragement, numerous terrorist groups used violence against civilians to try to stem Jewish immigration.

A history of violence in modern Jerusalem

The British mandate over Palestine ended in 1947, at which point the United Nations proposed a plan that would divide Palestine into a Jewish state and an Arab state. This plan didn't play out, however, as the Arabs didn't go for it, leading to Israel declaring independence in 1948. As the Encyclopedia Britannica explains, this led to the first — but certainly not last — Arab-Israeli war. Forces from five different Arab nations invaded and occupied areas in eastern and southern Palestine and captured east Jerusalem. The 1948 war saw Jerusalem (and Israel) divided, with the terms of the armistice meaning that the West Bank became part of Jordan and the Gaza Strip became part of Egypt. Israel remembers this war as its war of independence, and after it, Jerusalem was declared its capital.

According to History, there has been no shortage of conflicts between Arabs and Israelis since 1948, including the Suez Crisis in 1956 over control of the Suez Canal; the Six Day War in 1967, in which Israel retook control of the Gaza Strip, the West Bank, and the Golan Heights; the Yom Kippur War in 1973, once again over control of the Golan Heights; the Lebanon War in 1982; and numerous uprisings and violence by militant groups. To this day, both sides claim Jerusalem as their capital, so many countries keep their embassies in Tel Aviv until a resolution between the two groups can be reached.