Can A US Supreme Court Justice Be Removed?

On Tuesday, November 10, 2020, the Supreme Court took up a Texas-lead challenge to the Affordable Care Act, the controversial healthcare law known colloquially as Obamacare. With three conservative justices appointed by President Trump – the most recent being Justice Amy Coney Barrett, who replaced the late Ruth Bader Ginsberg just weeks before the 2020 Presidential election — the third challenge to the healthcare legislation and the new 6-3 conservative majority on the high tribunal have people wondering if a Supreme Court justice can be removed from the lifetime appointment for any reason.

According to Fast Company, the answer is yes — theoretically. It has never happened, however. Section 1 of Article 3 of the Constitution states that federal judges and Supreme Court justices "shall hold their Offices during good Behavior," meaning they can be impeached for conduct unbecoming of a member of the highest court in the land. Since there is no constitutional definition of naughtiness, and with the two-party government growing ever more entrenched in opposing political ideologies, that criterion isn't so easy to prove.

During his appointment hearing, Associate Justice Brett Kavanaugh notoriously defended accusations of sexual assault as a young man by yelling at senators and vociferously professing his love for beer, behaviors which did nothing to slow down his confirmation to the bench. In fact, only one justice has been impeached since the establishment of the Supreme Court in 1789, and he was not removed from the court.

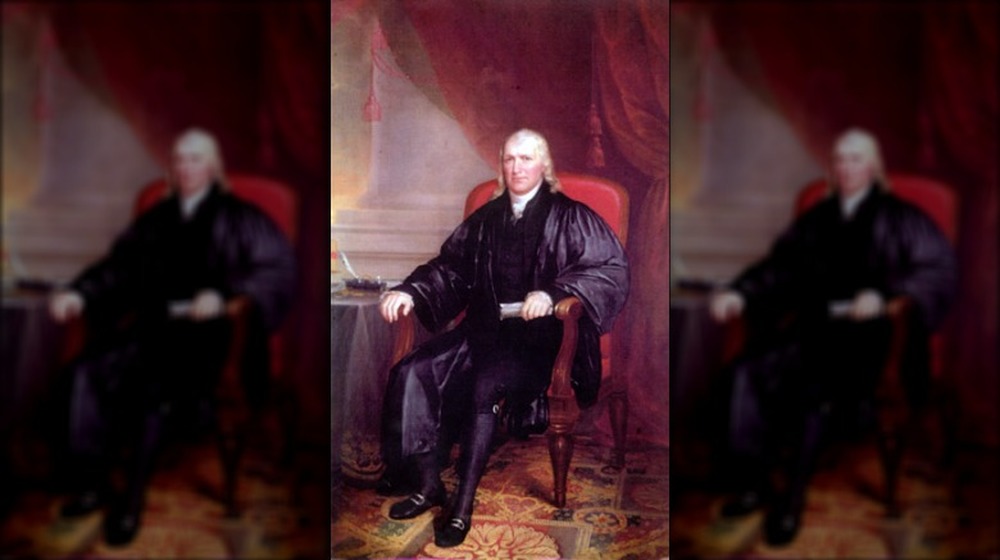

Samuel Chase: the archetypical 'obnoxious justice'

According to the U.S. Senate website, the only impeachment of a Supreme Court justice — and third of a public official — in the nation's history was in 1804. The first was in 1789, when a senator who had previously been expelled for treason was put on trial but ultimately acquitted. The second impeachment trial successfully relieved a federal judge of his appointment in 1804 on the grounds of drunkenness and insanity. The third such trial was of Supreme Court Justice Samuel Chase, who began his term on the court in 1796. The Senate website describes him as a "staunch Federalist with a volcanic personality" who had become a political enemy of President Thomas Jefferson. At the behest of Jefferson, Representative John Randolph from Virginia organized impeachment proceedings against the "obnoxious justice." The members of the House made the case that Chase tended to "prostitute" his appointment "to the low purpose of an electioneering partizan [sic]," i.e., they didn't like his politics.

If that case sounds a lot like how these governmental processes tend to play out today, the end of the story shouldn't surprise you. Although the House voted to impeach Chase, the Senate ended up acquitting him of all charges, and thereby set a precedent protecting the judiciary from future attempts by the Congress to remove justices based on political opinions. Chase served on the court until his death in 1811.

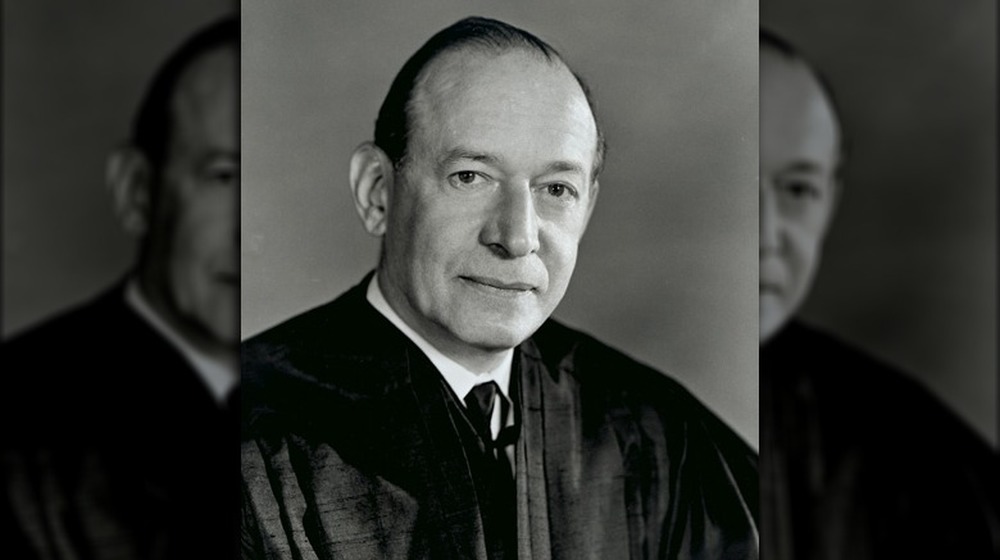

One Supreme Court justice removed himself from the bench out of fear of impeachment

Although no Supreme Court justice has been officially ousted by the process of impeachment, the threat of such a trial has caused one justice to remove himself out of fears of being history's first. Associate Justice Abe Fortas voluntarily resigned from the bench in 1969, despite maintaining that he had done nothing wrong. As Politico reported, it was the first time a Supreme Court justice had resigned due to the threat of impeachment.

Having been confirmed to the court in 1965, Fortas was nominated by President Lyndon B. Johnson to replace Earl Warren as Chief Justice in 1968. But Fortas faced powerful opposition from the Senate confirmation committee due to the close relationship he maintained with LBJ during his time on the bench. Conservative senators organized a filibuster against his nomination, drawing attention to a $15,000 payment he had received for giving university seminars. When Fortas realized he didn't have the support necessary to overcome the opposition, he asked the president to withdraw his nomination. He was the first chief justice appointee to fail to win Senate confirmation since 1795.

Fortas's tenure on the Supreme Court would ultimately be cut short after it was revealed that he had accepted a lifelong annual $20,000 retainer from the family foundation of a prominent Wall Street investor for legal advice, the nature of which was never specified. He stepped down from the lifetime appointment on May 15, 1969.