The Tragic Real-Life Story Of The Last Member Of The Yahi

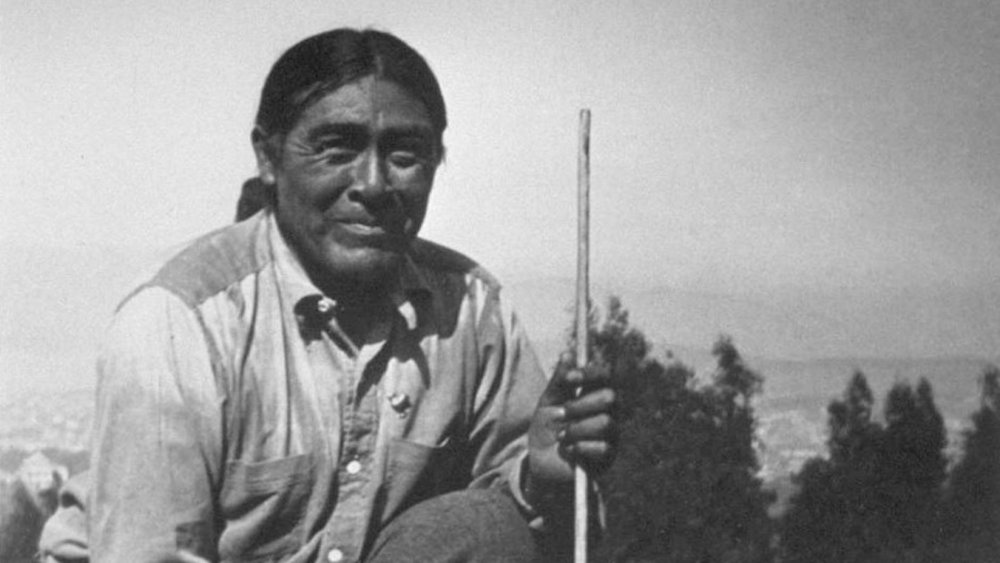

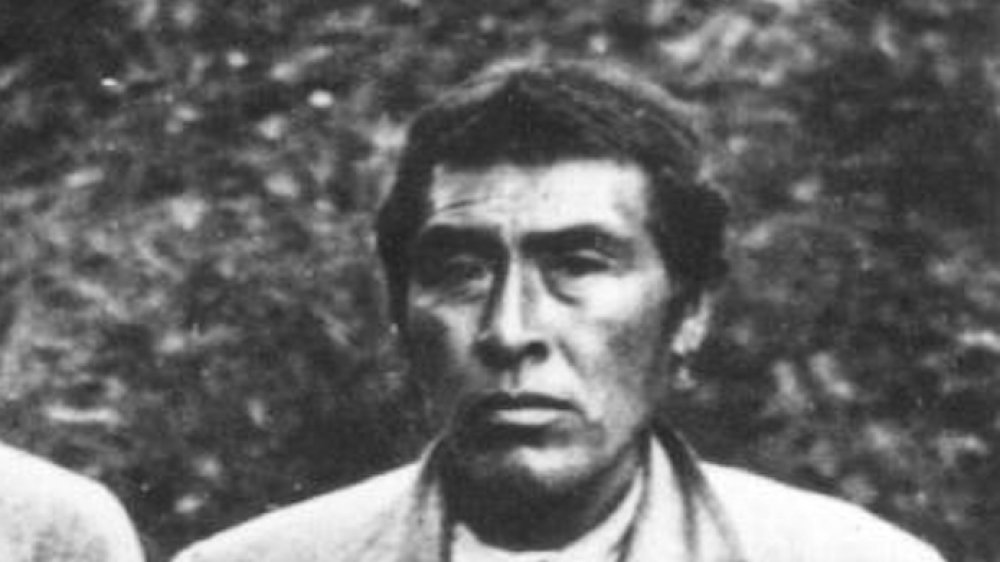

In his lifetime, Ishi watched as his people were literally wiped off the face of the Earth. From the 1840s to the 1870s, many Native people living in the California territory were either murdered or kidnapped, which led to the destruction of countless Native groups. Ishi came from the Yahi, a subgroup of the Yana people, and after hiding in the forests for years, surviving numerous massacres, he became known as the "last Yahi" after wandering into Oroville, California in 1911.

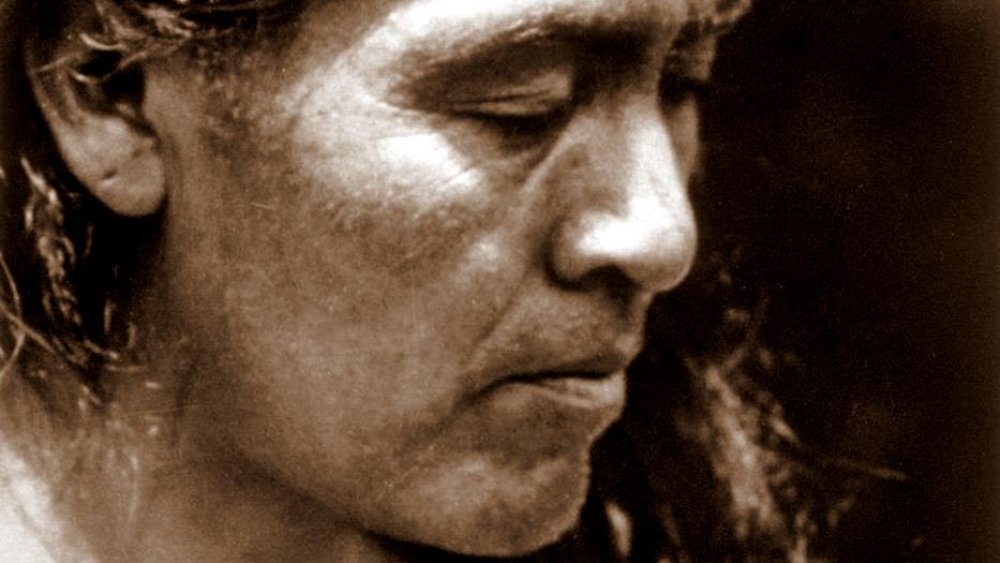

Despite his experiences, Ishi was often described as "remarkably affable and friendly." But he was exploited till the end of his life and even afterward by those seeking to advance their careers. Housed at the Phoebe Hearst Museum of Anthropology, he became a living exhibition for white visitors to marvel at. Unfortunately, this constant exposure to strangers is thought to have contributed to Ishi's premature death from tuberculosis.

Throughout his time at the Museum of Anthropology, Ishi was recorded telling hours upon hours of stories as he recounted the history of his people in his own way. Many of these stories remain untranslated, and even at the time of their telling, few understood the last breaths of the Yahi language.

Ishi died in 1916, but his body still suffered the consequences of scientific racism until it was finally accorded a proper burial almost 85 years later. This is the tragic real-life story of the last member of the Yahi.

A short history of the Yahi people

The Yana Native people once lived in what is now considered California along the Sacramento River, from the southwest of Lassen Peak to the Pit River. Before the European invasion, there were four distinct groups within the Yana—Yahi, Northern, Central, and Southern Yana—all of whom spoke different dialects that were mutually intelligible. According to AAA Native Arts, while the Yana were once considered to be their own linguistic group, they are now placed within the Hokan language family.

The first encounter with Europeans occurred in 1821 when a Mexican expedition stumbled upon the Yana and after 1828, land grants were occasionally given to Mexicans in Yana territory. It's estimated that the Yana initially numbered between 1,500 and 3,000, within which the Yahi numbered around 400, per the University of California San Francisco.

But once Anglo trails and settlements began invading through Yana territory, the conflicts became more and more brutal. And once Mexicans gave control of California over to the United States in 1846, the United States began a genocide that claimed the lives of thousands of Native people in the territory. While this genocide was propagated by the claims that white people were in danger, according to "Genocide and the Indians of California" by Margaret A. Field, less than 50 deaths of white people can be attributed to the Yana.

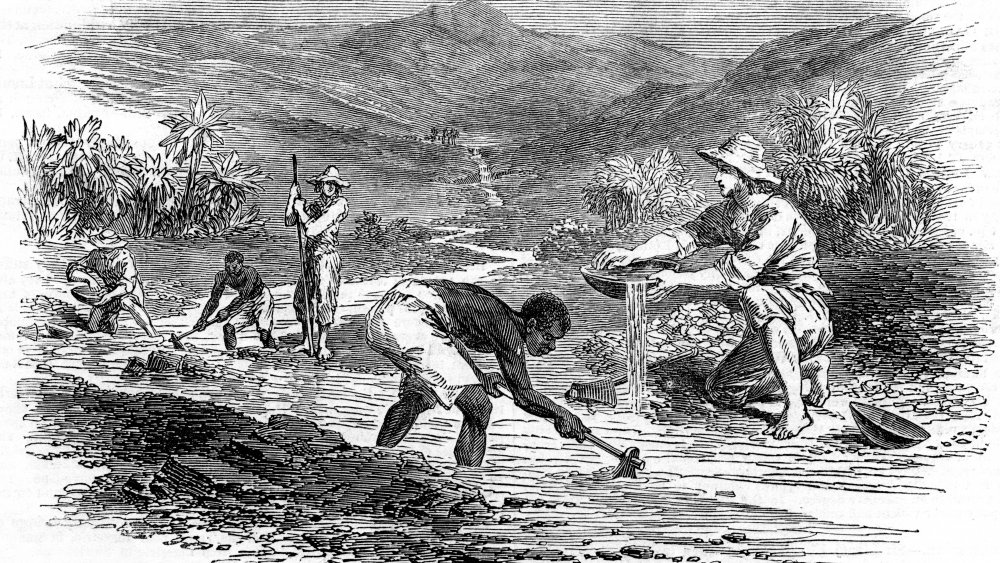

The horrors of the gold rush for the Yahi

As encounters with Spanish-Mexicans brought endemic and epidemic disease to Yana people along with the destruction of their food supply, the discovery of gold in California was about to have another devastating effect.

According to Newsweek, starting in 1848, white civilians, along with the United States Army, set out on mass killings in order to "labor much longer in the mines with security." Once gold was discovered, over 90,000 potential gold miners flooded into northern California.

Soon, the invading white settlers had completely destroyed the Native food supply. And when Native people went after white peoples' sheep and cattle, they were attacked even more heavily in retaliation.

Many of the state militias, at least 24 of whom were authorized by California governors, also enjoyed a great deal of financial support from the government. According to the Los Angeles Times, in the 1850s, the California state legislature passed three bills that allocated up to $1.5 million for anti-Native militias. Most of this money often went to the bounties paid to white people for their weapon supply and for the deaths of Native people. According to Indian Country Today, the payment for a bounty was 25 cents per scalp and five collars for a whole head.

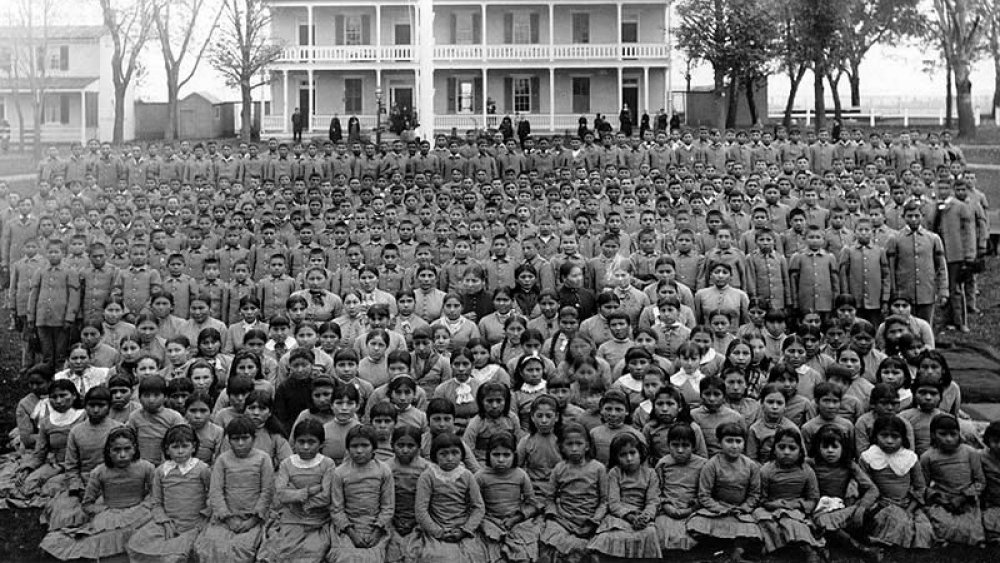

In 1850, the state of California also legalized indentured servitude of Native people and Native prisoner leasing. This led to an increase of "violent kidnappings" and regular arrests. Between 1850 and 1863, upwards of 10,000 Native people were indentured or sold.

The Yahi who survived the Three Knolls Massacre

Ishi was between five and six when he and his family survived the Three Knolls Massacre in 1866. Following the Workman and Silva massacres of 1865, which claimed the lives of over 70 Yahi whose children were sold to local ranchers, 40 more Yahi were brutally slaughtered during the Three Knolls massacre.

Ishi and his mother managed to escape by floating amongst the dead bodies down Deer Creek. In 1871, they also survived the Kingsley Cave massacre and went into hiding. According to Native Americans in Philanthropy, only 15 people survived the massacre that claimed the lives of 30 Yahi.

As a result of starvation, disease, and massacres, the population of the Yana was reduced by 95% between 1850 and 1870. In an attempt to avoid the genocidal invaders, what remained of the Yana and the Yahi hid out and lived in isolated canyons in an attempt to avoid detection, Britannica explains.

During this time, Yana of all ages who were working on farms and living in towns were also targeted. When several young Yana girls were murdered in front of their employers, the leader reportedly declared "We must kill them, big and little."

The attack of 1908

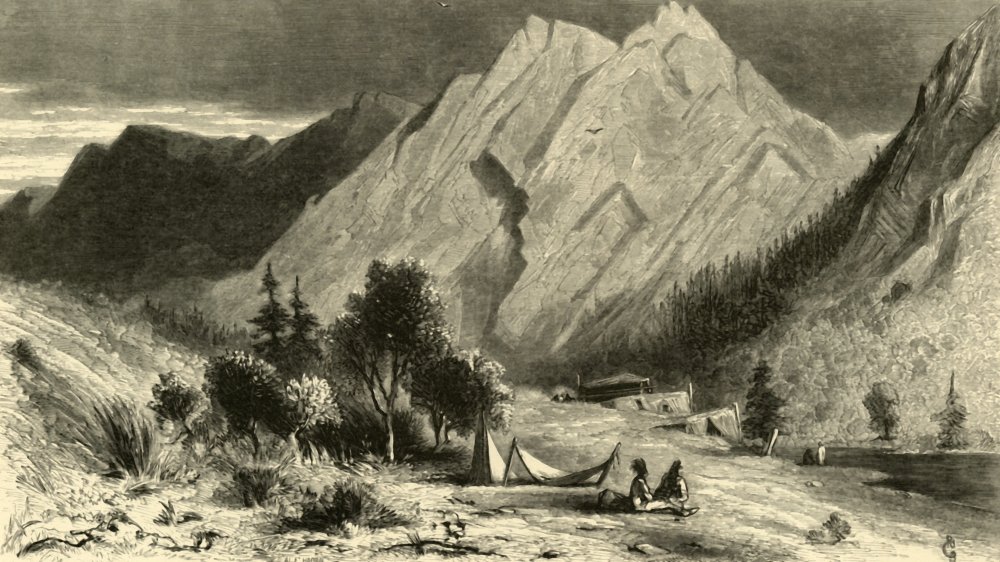

Ishi and his family hid out in the canyons undetected for over 40 years until a group of surveyors stumbled upon their camp in 1908. Ishi was reportedly fishing when the surveyors saw him and, according to Ishi in Two Worlds: A Biography of the Last Wild Indian in North America, when Ishi noticed the surveyors he "motioned them emphatically back, saying over and over something which surely meant 'Go away!'"

But the next day, the surveyors set out to find the Yahi. Unfortunately, Ishi and his sister were with their mother who was bedridden and another old man who was weak and slow, and they could do little to prevent the white people from coming into the Wowunupo village.

Covering Ishi's mother with hides and blankets in the hope that she may go unnoticed, Ishi, his sister, and the old man ran and hid when the white surveyors came into their village. Although the white men didn't harm Ishi's mother, they ransacked the village, taking "every movable possession, even the food." When Ishi returned to the camp, it was empty apart from his sick mother. His sister and the old man never returned and they were never to be reunited.

The 1911 capture of the last of the Yahi tribe

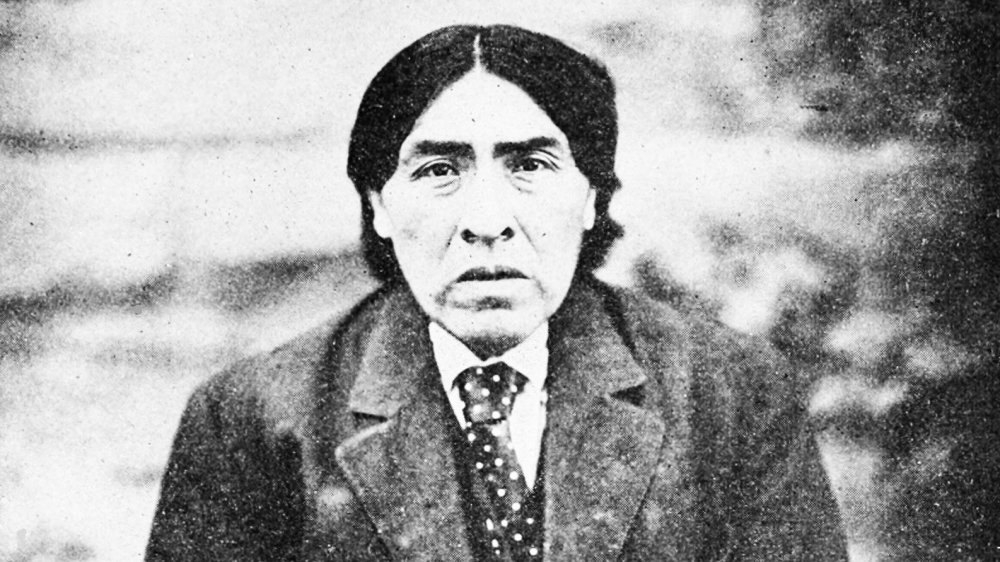

Ishi's mother died shortly after the incident with the surveyors and Ishi spent the next three years alone. Ishi believed that his sister likely hadn't survived long either, for they had a shared knowledge of familiar places and if she was alive, they would've likely found each other. As a sign of mourning, Ishi burned his hair short, as it was when he ventured into Oroville, California in 1911.

According to Mohican Press, on August 29th, 1911, Ishi came by a slaughterhouse two miles away from Oroville. He was "emaciated, exhausted, frightened, and starved." He was promptly turned over to the local sheriff, who locked Ishi in jail.

Ishi soon caught the attention of Alfred L. Kroeber and T. T. Waterman, both of whom were anthropologists at the University of California. Within two days of Ishi's discovery, Waterman was on a train ready to take ownership over Ishi. Although the Bureau of Indian Affairs sought to relocate Ishi onto a reservation as a ward of the government, Kroeber convinced them to give him guardianship over Ishi and resettle him instead into the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Art and Anthropology of the University of California.

However, communication was difficult as Ishi didn't speak Spanish, English, or any locally recognized Native language. Waterman was barely able to communicate with Ishi "through a Yana dialect that Kroeber has recorded," according to Jay Hansford C. Vest, Ph.D.

Ishi and the Museum of Art and Anthropology

Ishi spent the rest of his life living at the Museum of Art and Anthropology of the University of California, Berkeley. In addition to Kroeber's studies about Yahi culture and language, the museum employed Ishi as a janitor for $25 per week.

But according to the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, Ishi spent most time "on display for white museum audiences." As observers watched, Ishi fashioned arrows out of colored glass and obsidian, and there's "no historical evidence that shows if Ishi had a choice in the matter."

Kroeber and Waterman also made recordings of Ishi, asking him to recount his people and his culture. When Kroeber invited several reporters to meet Ishi, Ishi wouldn't answer questions about his past. Instead, he told a story about Wood Duck searching for a bride, a story that lasted six hours. Although the phone rang several times during the tale, Ishi objected to any interruptions. During his time at the Museum of Art and Anthropology, Ishi made over 400 recordings on wax cylinders.

According to Living on Earth, although Waterman made a partial translation, the story has still not been translated in its entirety. While the story of Wood Duck is likely an ancient story, researchers still struggle to understand the various stories that Ishi told. Ishi passed on knowledge about Yahi life "through stories about the natural world," the way his people had for thousands of years, and even when translated, their meanings eluded the anthropologists.

No people to name me

Ishi's real name is not in fact "Ishi." This moniker was given to him by Kroeber, and it's actually just the word for "man" in the Yana language. According to Native Americans State by State by Rick Sapp, in Yahi culture, tradition required that a person not speak their own name unless formally introduced by another Yahi. In this way, names weren't given to enemies or outsiders unless there was the intermediary of a friend making introductions.

According to Ishi in Two Worlds by Theodora and Karl Kroeber, reporters refused to accept that Ishi was unable to give them his name. Sam Batwi, an English-speaking Yana who helped researchers communicate with Ishi, tried to persuade Ishi into revealing his name but he was unwavering. In an attempt to dissuade people from continuing to ask, Ishi responded, "I have none, because there were no people to name me." As a result, Kroeber christened him Ishi.

In Yahi culture, one also didn't speak of anyone who was dead, which also immensely frustrated researchers as they struggled to learn about the Yahi people from Ishi.

Ishi, the last of the Yahi, may have had mixed ancestry

Although Ishi was referred to as the "last Yahi," researchers in 1996 determined that Ishi was most likely not the last "full-blooded Yahi." According to UC Berkeley, research archaeologist Steven Shackley has theorized that Ishi was of mixed Native ancestry based on the arrow points made by Ishi. While the arrow heads that Ishi made were "long blades with concave bases and side notches," arrowheads found in historic Yahi areas are much shorter, "with contracting stems and basal notches."

This discrepancy has led Shackley to suggest that Ishi was not a pure Yahi, and was instead a mix of Yahi and Nomlaki or Wintu, from whom he learned how to make projectile points. This suggestion is not unlikely. According to the Library of Congress, as Native populations suffered genocide and extinction, there was more and more intermarriage amongst Native tribes, even with those who'd been enemies at one point, "to try to forestall their mutual extinction."

According to Returns: Becoming Indigenous in the 21st Century by James Clifford, recent archaeological evidence suggests that the group distinguished as the "Yahi" were much more mixed and diverse than previously assumed. And with countless children forced into labor, it's impossible to know if Ishi truly was the "last" Yahi. But nevertheless, any Yahi that survived would likely have been forcefully assimilated.

The last five years of Ishi's life

For five years, Ishi made a "Yahi house," arrowheads, and demonstrated archery when he wasn't working as a janitor or being interviewed about his life. According to Indian Country Today, Ishi was put on display as children and visitors came through to stare. Thousands of people would come through to see him and for Ishi, this was the most people he'd ever seen in one place.

The museum also gave Ishi a bow with which to show off his archery skills to the audience, but most likely the museum chose a random bow from their exhibits, oblivious to whether or not the bow was actually one used by the Yahi. Ray Clar remembers seeing Ishi in the exhibit when he was a child and notes that Ishi was a "lousy shot" and that Ishi seemed to be angered by the bow.

According to Ishi in Three Centuries, edited by Karl and Clifton B. Kroeber, despite Ishi's discomfort and stress around crowds, Kroeber not only kept him performing as a living exhibit but even took him to perform at the Panama-Pacific Trade Exhibition, also known as the 1915 World's Fair in San Francisco.

The Panama-Pacific Exhibition was meant to celebrate American imperialism and the opening of the Panama Canal. Ishi's presence as the "last Yahi" was intended to parallel James Earle Fraser's statue entitled "The End of the Trail," which featured a nondescript Native person slumped over on a horse in defeat.

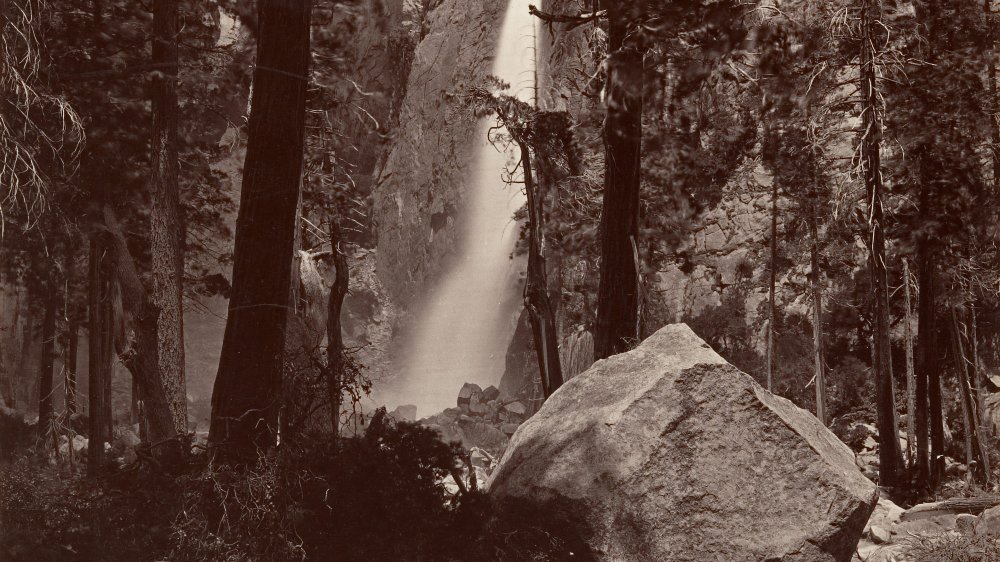

The last of the Yahi returns to Deer Creek

In 1914, Kroeber forced Ishi to return to Deer Creek. Kroeber wanted Ishi to show him what life had been like, but for Ishi, it meant going back to a land haunted by massacres. Kroeber insisted on going and although Ishi refused several times, in the end, he agreed.

Right before they were to leave, Ishi learned that the food for the trip had been stored in the bone room of the museum. He once more refused to go, insisting that the food was now contaminated. After the scientists claimed that they'd replaced the food, Ishi reluctantly agreed once more. However, it's unknown whether or not the scientists actually honored Ishi's request. Upon leaving on the expedition, Ishi realized that two of the guides hired by Kroeber were part of the group of surveyors who'd ransacked his camp in 1908. The two men even showed off some of the artifacts they'd stolen from the camp and while Ishi watched silently, Kroeber haggled with the men for some of the artifacts.

As Ishi took the expedition around Yahi country, Kroeber drew maps and wrote down their names as Ishi recalled them. Overall, Ishi named over 180 places for Kroeber.

But for Ishi himself, the journey back to a land soaked in blood and memory was draining. According to LARB, when Ishi came upon his mother's burial plot, he wept. And on one day, Ishi claimed that he'd heard his sister and mother's voices on the path.

Frequent battles with illness

Having spent most of his life apart from white people, Ishi had limited immunity against diseases and was often ill. And unfortunately, according to the Dream Endures: California Enters the 1940s, museum visitors loved touching Ishi and shaking his hand.

This likely explains Ishi's common bouts of sickness. Ishi himself never became comfortable shaking hands and tried to avoid it as much as possible. However, in the end, he relented, though he never initiated the gesture.

Due to frequent illnesses, Ishi met Doctor Saxton Pope. Ishi taught Pope how to shoot arrows and the two of them often went to Sutro Forest to target practice. Unfortunately, despite their "friendship," Pope was the one who insisted on autopsying Ishi and examining his brain against his wishes, claiming that it was "in the interest of science."

Ishi was repeatedly hospitalized for tubercular infections from 1914 to 1916 and on March 25, 1916, Ishi died from tuberculosis at the UC Hospital. But Saxton wanted to take one last photo before Ishi died. Saxton posed with a bow and arrow behind Ishi who sat on the ground, and upon seeing the photo later, Saxton remarked at "what a pitiful condition he'd been reduced. [And] had this been apparent before, I should not have asked this exertion of him. Ishi's final words were reportedly, "You stay, I go."

You stay. I go.

After Ishi's death, Kroeber protested against an autopsy since Ishi himself had stated that he'd wanted his body to be cremated, especially after seeing what happened to bones and remains that the museum appropriated.

In a letter written the day before Ishi died, Kroeber insisted on Indigenous burial rights, writing that "if there is any talk about the interests of science, say for me that science can go to hell," per An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States. Kroeber also accurately pointed out that the university, along with many others across the United States, has "hundreds of Indian skeletons that nobody ever comes near to study." However, the letter arrived too late and despite knowledge of Ishi's wishes, Ishi's brain was removed and preserved.

According to SFGate, Kroeber ended up shipping Ishi's brain to the Smithsonian where it was promptly cataloged and forgotten about. The brain wasn't found again until 1999, when researchers tracked the brain down in order to repatriate it to his tribal relatives after a delegation of Northern California Native People started looking for Ishi's brain in 1997 in order to give him a proper burial along with his cremated remains.

Although the Smithsonian initially refused and denied even having the brain, in 2000, Ishi was repatriated to the Pit River Tribe and fully laid to rest.