The Greatest Mathematician Of Ancient Alexandria Was A Woman

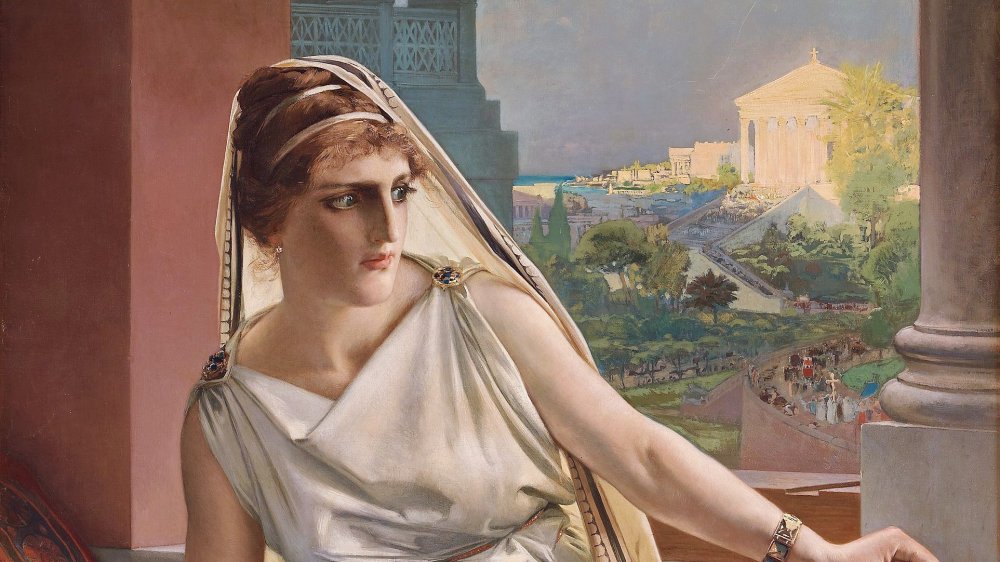

For the people of the ancient world, science was a big deal. It wasn't just that the subject was a way to understand concepts like addition and subtraction. Math, the sciences, and philosophy were even, for some, a way to get closer to the divine. One of the greatest of these ancient philosophers was a mathematician, teacher, and all-around master who also happened to be a woman.

Her name was Hypatia. According to Britannica, she was born in Alexandria, Egypt, around the year 355 C.E. She is the first woman whose life and work as a scientist and educator is complete enough to get a sense of her life, though many details remain obscured. We aren't totally sure when she was born, or who formed the rest of her family, apart from father Theon.

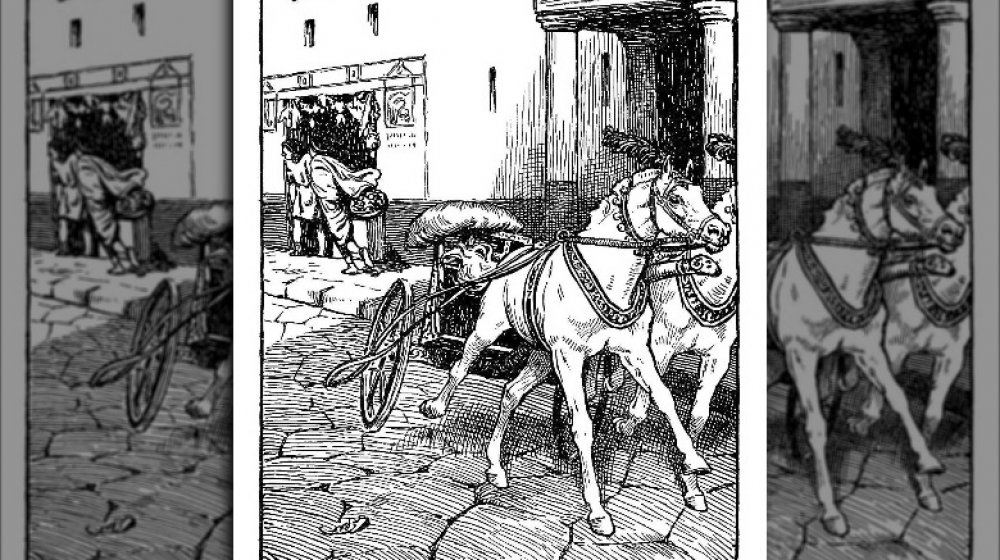

Hypatia's story may be best known for its end. In 415 C.E, a Christian mob tore her from her carriage and murdered her, reports Hypatia: The Life and Legend of An Ancient Philosopher, by Edward Jay Watts. The exact details vary, though some accounts get pretty gruesome. After her demise, the intellectuals of Alexandria fled, recognizing that the city had become too regressive and violent under the influence of Cyril, a powerful local bishop.

Yet, there is more to Hypatia's story than this sad end. She was, by all accounts, a brilliant woman who was deeply tied to Alexandra's reputation as a center of learning and progress. Hypatia was both a remarkable individual and an example of the intellectual life and death of the ancient world.

Hypatia was unlike other ancient women

For most Greek and Roman women, life was pretty restricted. The exact details of how a woman was constrained varied quite a bit depending on her station in life, where she was born, the time she lived, and even random accidents and happenstance. However, for a great many women of Hypatia's time and place, there was really only one option: marriage and motherhood. Few women could expect more than that, and very few indeed dared to dream of things like having rights or independently directing their own lives.

Hypatia proved that there were exceptions to this potentially crushing existence. Not much is known about her early life, but sources like the Ancient History Encyclopedia give a few details. She was the daughter of Theon, a mathematician respected in Alexandria and beyond for his own intellect. Instead of learning how to weave cloth or serve a future husband, Theon tutored his daughter in math, astronomy, and philosophy.

This wasn't totally beyond the pale, says Hypatia, as daughters of intellectuals would need to manage their own children's education. How could a poorly taught wife know if a teacher was worth the family's time and money, after all? Other well-educated women show up in the records around this time, too, like the writer and empress Eudocia. Yet, it's clear that Hypatia's education went above and beyond, as she became a teacher and well-regarded public figure, unlike many other intellectual women of her time.

Hypatia was born in an intellectual city

Fourth and fifth century Alexandria wasn't some forgotten backwater of the Mediterranean. Rather, it was one of the intellectual centers of the ancient world, bringing some of the greatest minds of the time all in one place.

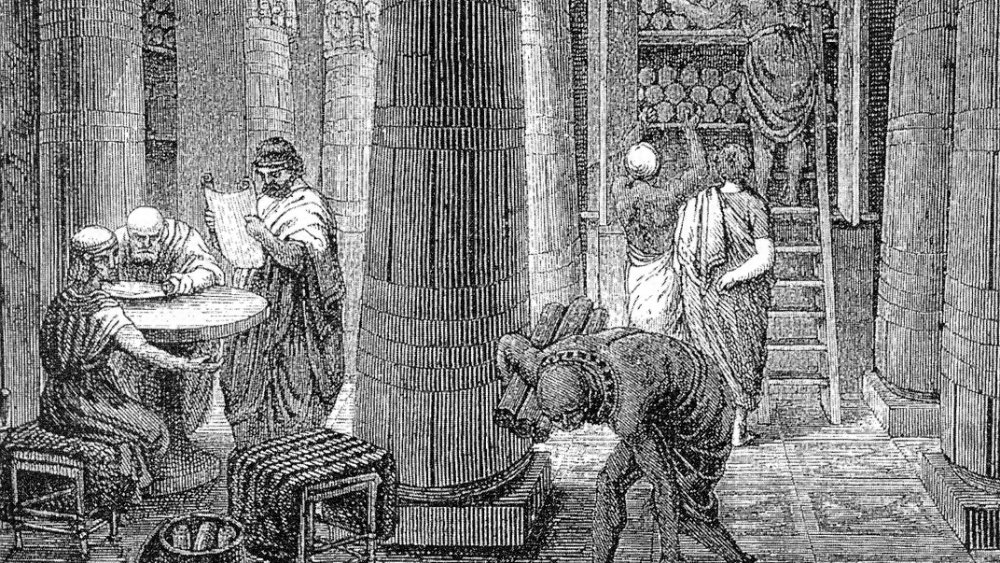

According to the Ancient History Encyclopedia, Alexandria was founded in the fourth century B.C.E. by Alexander the Great, who humbly named an entire city after himself. Though Alexander went off to conquer more land, as was his habit, he was reportedly returned to his namesake settlement after his death. The city came under the rule of his general Ptolemy, and the Ptolemaic dynasty that followed managed Alexandria until 30 B.C.E.

What made the city so attractive for ancient nerds? Alexander himself had the beginnings of a grand vision, The Guardian reports. He and his successors thought that Alexandria could gather up all of the accumulated knowledge of the ancient world and preserve and interpret it for generations to come. To that end, people built the famed Library of Alexandria, perhaps then the largest one on the planet. They also constructed a musaeum, or literally "temple to the muses," that acted as an early kind of university where scholars and intellectuals of all sorts came to teach. However, it was something of a fallen world. Smithsonian Magazine indicates that the library and museum were probably fully gone by 391 C.E., during Hypatia's lifetime but before her death.

Religious conflict was tearing Hypatia's city apart

By the time Hypatia was born around 355 C.E., Alexandria had lost its shine. It was still considered an intellectual center, and of course there was that glorious library and university. But trouble was brewing in the streets and temples.

The trouble, perhaps unsurprisingly, stemmed from religious discord, specifically between the devout and increasingly powerful Christians and established pagan believers. PBS reports that, in 313 C.E., the Roman Emperor Constantine issued the Edict of Milan, which officially accepted Christianity as a religion and ended persecution of what was then a Christian minority. Only ten years later, Constantine made Christianity the official state religion of Rome.

After more than a century as the sanctioned religion of the land, however, conflict was still the name of the game. According to Hirundo: The McGill Journal of Classical Studies, Alexandria of the fourth and fifth centuries was a hotbed of religious conflict. Plenty of people still preferred to worship the traditional gods. Alexandria was also home to an established Jewish community.

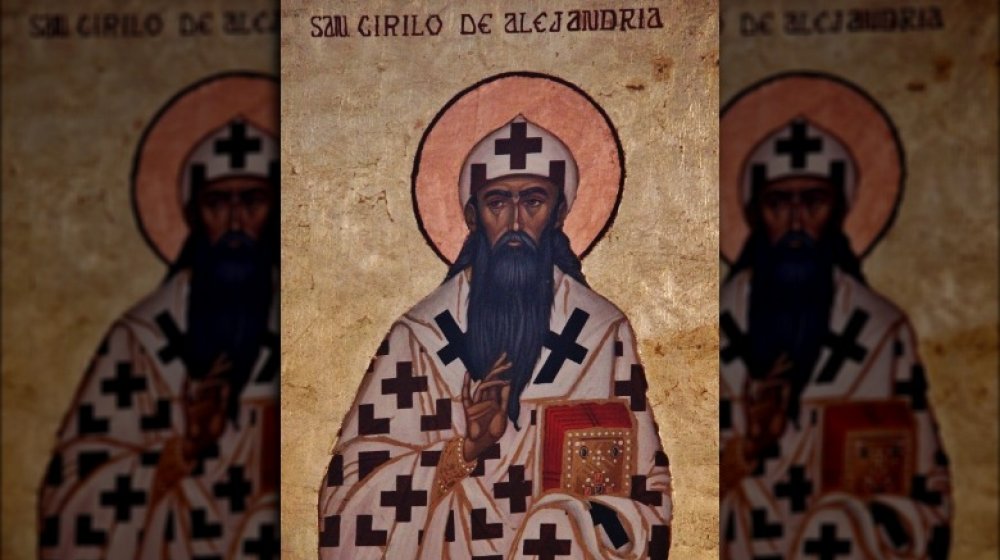

None of that was okay with Cyril of Alexandria, the local bishop. When he wasn't busy arguing with other church leaders, Cyril whipped his followers into a frenzy. He encouraged virulently anti-Semitic sentiments that culminated with his expulsion of the Jews from Alexandria in 415 C.E., the same year of Hypatia's death. Cyril also butted heads with Orestes, the local Roman prefect or governor, who may have been a moderate Christian himself.

The math of Hypatia was scientific and spiritual

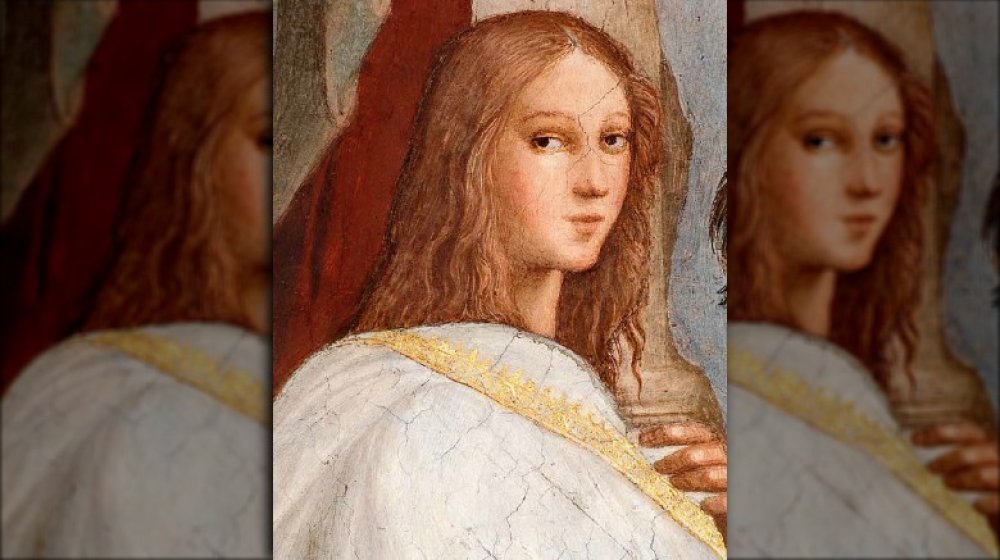

Hypatia was a student and teacher of Neoplatonism, a philosophy that sought to unite people with the divine through study of ordered subjects like math. For her and other scholars of the time, philosophy wasn't just some navel-gazing undergraduate exercise or the vague study of knowledge, but science itself. Furthermore, it wasn't just an attempt to learn more about the world. It was also part of a larger effort to become one with God.

According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Neoplatonism was developed by followers of Greek philosopher Plotinus in the third century C.E. and encompasses a broad range of ideas. The central concept of most of these ideas focuses on the existence of "the One," the ultimate principle of all things and the source of everything. To get closer to the ineffable divine force and attain perfection on Earth, many Neoplatonists like Hypatia believed that we needed to carefully study and contemplate the world around us.

Sciences like astronomy and mathematics were therefore part of this quest to attain a more perfect union with the One. Science and religion, or at least spiritual and philosophical belief, were intimately tied together. For her part, Hypatia was never recorded as having worshipped any particular deity. Because she was not Christian or Jewish, many writers described her as a pagan, which became a catch-all term for anyone who didn't practice a monotheistic religion. Eventually, this would put Hypatia in a very dangerous situation.

Hypatia fostered a nonpartisan environment in a fractured time

Though Christianity was an increasingly powerful religious and political force, Hypatia herself seems to have done her best to stay above the fray. As she grew in prominence as a scientist and philosopher, Hypatia taught a wide variety of people, including Jewish students, Christians, and pagans. According to Hypatia: The Life and Legend of an Ancient Philosopher, this was possibly an attempt to show that philosophy, if practiced correctly and with equality in mind, could offer a solution to the turmoil wracking the city. Hypatia, who over the course of her life became a widely respected public figure, would have been well aware of the religious warring that was tearing Alexandria apart.

The schools of Alexandria were primed to teach everyone, argues the journal Verbum et Ecclesia. Alexandria hosted a museum, which was actually a kind of shrine and educational institution in one, along with its associated library, one of the largest collections of writing in the ancient world. The city was also home to a number of other schools, most notably the Serapeum and the Sebastion, while Hypatia herself likely taught in her own home. Students and teachers came from all corners of the known world to learn and exchange ideas. By Hypatia's time, numerous other cultures and belief systems had comfortably mingled for many years, including Jewish, Greek, and Egyptian cultures.

Hypatia never married

If the various sources relating her life aren't exaggerating, Hypatia was incredibly attractive, both intellectually and physically. She was apparently a compelling teacher, had an engaging wit, and was widely respected by many people in Alexandria and beyond, Cyril and his followers excepted. Yet, she never married. Why would Hypatia abandon what was a central aspect of so many other women's' lives?

That was very likely a feature of her life plan, not a flaw. According to Hypatia, her celibacy was tied to her philosophy of Neoplatonism. To study, teach, and gain a closer understanding of the ultimate purpose of the universe, Hypatia likely did not want any earthly distractions, which included family life. For pagans like her, this was a complicated matter with no easy answers. Some philosophers did have relationships and produced children, though it seems as if they were all male. Hypatia may have recognized that, as a woman, she would very likely have been expected to at least manage the raising of children and a household, all of which would have put a serious dent in her philosophizing time.

Hypatia's celibacy also shielded her from controversy. No student could claim to have compromised her or wield power over her. It also served as a powerful illustration of her ideals, which included temperance and a devotion to study above all else. To maintain her unique position, then, Hypatia probably decided that marriage and motherhood would have to pass her by.

Hypatia was a serious intellectual powerhouse

Why was Hypatia such a big deal, anyway? There were plenty of teachers and schools in Alexandria. What about her stood out, apart from the obvious fact that she was a woman?

Turns out that she was the real deal, intellectually speaking. According to Lapham's Quarterly, Hypatia was an active intellectual who developed some real solutions to problems faced by people of her time. She wrote many treatises and commentaries, though few of them survive. She's credited with designing the first hydroscope, a tool used to see objects far underwater. Hypatia also created the first known astrolabe, an astronomical and navigational tool that was used, in one form or another, through the 16th century.

Hypatia even improved on the process of long division, which is a more respectable feat when you consider that she was working with Roman numerals instead of the more compact Arabic ones most of us use today.

Of course, things could get twisted pretty easily. For the growing movement of hardline Christians, Hypatia's idea that the divine and intellectual inquiry were linked was cause for concern. According to the Ancient History Encyclopedia, she was eventually accused of witchcraft. One chronicler, John of Nikiu, writes of her "satanic wiles," saying that Hypatia was "devoted at all times to magic." If she weren't already dead at the time, Hypatia herself would probably beg to differ.

The Roman governor got Hypatia involved in a fatal fight

Cyril, the archbishop of Alexandria, was proving to be a problem. From the perspective of Orestes, the prefect of Egypt and essentially the Roman governor of the region, Cyril was fomenting rebellion and general violence throughout Alexandria. As per The Journal of Roman Studies, Cyril's expulsion of Jewish Alexandrians in 415 C.E. followed a reported massacre of Christians by Jewish radicals. Of course, from Cyril's perspective, he was defending his faith and bringing Christianity into power.

What's a Roman prefect to do? According to Smithsonian Magazine, Orestes turned to Hypatia for advice. On the surface, it was a perfectly reasonable thing to do. Hypatia was known for her wisdom and generally respected as a teacher. Unfortunately, it was to prove a fatal move, not for Orestes, but for Hypatia herself.

Any friend of Orestes was an enemy of Cyril's, it seems, though Cyril himself didn't say so outright. In fact, he kept carefully away from Hypatia. Instead, a convenient rumor began to surface that Hypatia was the reason Orestes and Cyril couldn't get along. Wouldn't it be convenient if this pagan woman, who spoke in public and taught men, just went away? Even worse, says Lapham's Quarterly, Hypatia was popular where Cyril wasn't. She also appeared to support those who resisted Cyril, from the relatively moderate Orestes to, perhaps, even the Jewish figures who resisted Cyril's grabs for power.

Hypatia was murdered by a Christian mob

A follower of Cyril named Peter, who conveniently lacked formal ties with the bishop, formed the mob that would spell Hypatia's doom. Led by Peter, they found Hypatia as she was moving through the city in her carriage. According to most accounts, like the one related by Lapham's Quarterly, the mob fell upon her and pulled the teacher and philosopher to the ground. She was dragged to a nearby temple, one that had been dedicated to the cult of a previous Roman emperor and appears to have been commandeered as new religious headquarters by none other than Cyril himself.

Again, there is no record that Cyril directly incited Peter's mob of insurgent monks to this act, but it's clear that he was at least partially responsible for slandering Hypatia's reputation. If Hypatia was changed in the minds of the people from a respected teacher to a pagan witch influencing government affairs, then it would be all the easier to dispose of her. In the temple, Hypatia was stripped naked and killed. The most gruesome accounts maintain that she was flayed alive, sometimes with sharp oyster shells. Her body was dismembered and paraded through the streets before being incinerated.

Hypatia's death spelled the end of Alexandria's intellectual reputation

Though Alexandria's reputation as an intellectual center was already fading by Hypatia's death, things got much worse after she was gone.

According to Lapham's Quarterly, Cyril ordered the pillaging and burning of many of the schools left in Alexandria, as well as the destruction of more pagan temples. Many intellectuals fled the increasingly violent city. Orestes disappears from the historic record, perhaps recalled to Rome or even ditching his post and leaving town of his own accord. Hypatia's writings, along with many of the other documents that had survived the destruction of the Library of Alexandria and the schools, were now finally lost. It was heretical knowledge after all and could have made Cyril and his associates look bad besides.

It's worth noting here that Cyril wasn't exactly a popular guy. Even within the church he was a controversial figure, to the point where he was, in the words of The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, excommunicated and condemned as a "monster, born and educated for the destruction of the church." However, Cyril never faced any serious consequences for Hypatia's killing and was, in fact, later elevated to sainthood, so his reputation remains deeply complicated.

Hypatia has become a complex symbol for modern people

In the more than 1,600 years after her death, Hypatia has become a feminist martyr, intellectual legend, and complicated symbol for many people. As per Esquire, she's even appeared in the popular afterlife comedy The Good Place, played by Lisa Kudrow as a football jersey-wearing goofball who confuses the heck out of nerdy philosopher Chidi.

The tale of Hypatia became, for many, a symbol of Hellenistic rationalism overtaken by a corrupt, fundamentalist church, says Hypatia. In this way, she's become something of a martyr for philosophy. Some versions of her death, after all, say that the mob gave her an out by offering to let her become a nun if she renounced her work and became a Christian. The fact that she died anyway points toward the possibility that the principled Hypatia declined, assuming that the offer happened in the first place.

She's also become a feminist symbol. According to Hypatia, two feminist academic journals have been named in her honor. It certainly makes sense that her story has been molded in this fashion, as she was a uniquely accomplished, powerful woman who worked independently for much of her life.