The Messed Up Truth About The West Memphis Three Murders

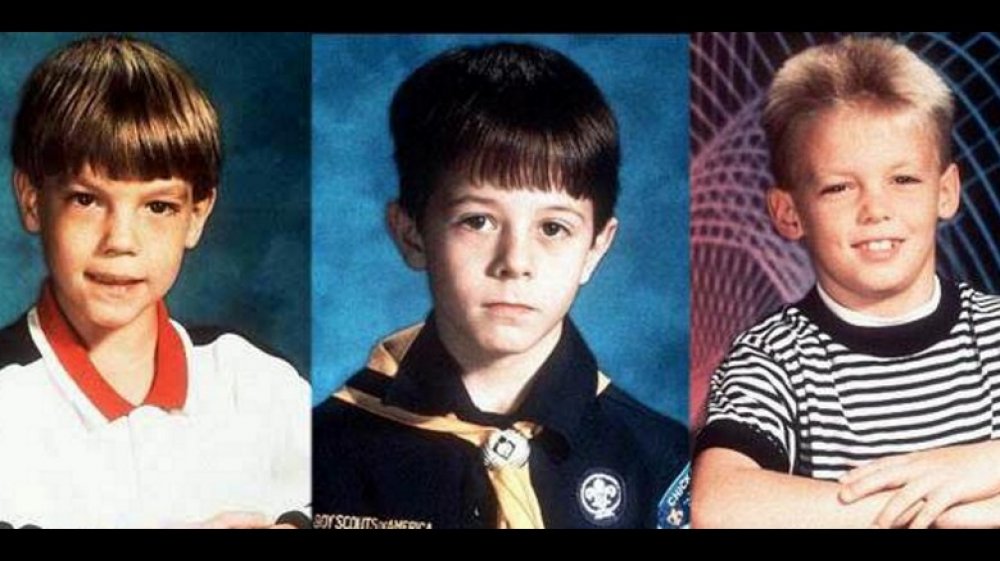

On the evening of May 5, 1993, three 8-year-old boys disappeared from the streets of West Memphis, Ark. Stevie Branch, Michael Moore, and Christopher Byers were best friends. Classmates at Weaver Elementary School, the three were active in their Cub Scout troop and responsible enough to be trusted to roam their neighborhood without supervision.

The following day revealed the unthinkable, when the bloodied and bruised bodies of the three boys were found submerged in a muddy creek in a wooded area called Robin Hood Hills. Two questions plagued the conservative, middle-class community: Why would anyone commit such a heinous act, and, more importantly, who?

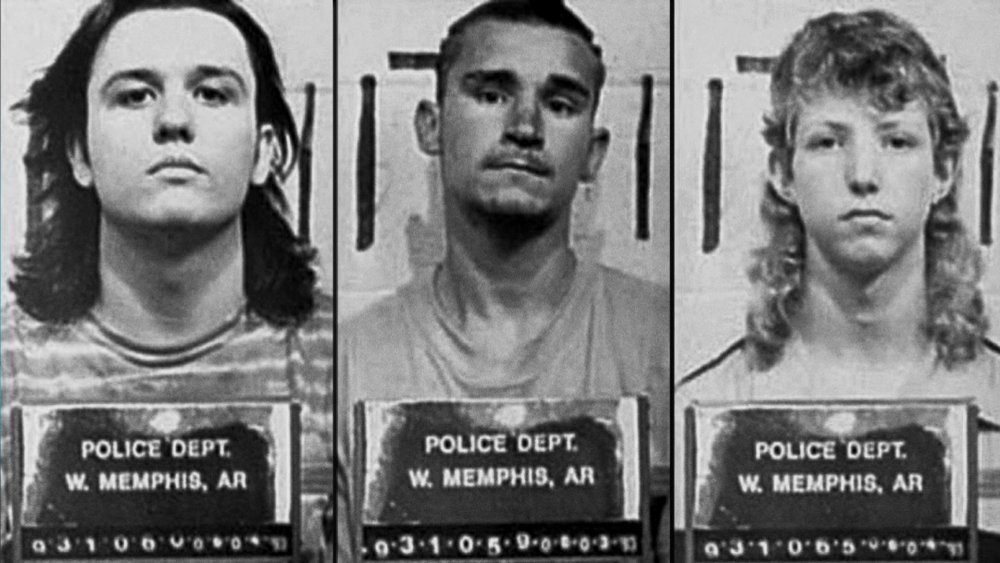

As rumors of a Satanic sacrifice swept the community, the minds of many in West Memphis were already made up. The only possible culprits were 18-year-old Damien Echols, a poor teen with an interest in the occult and a record of mental illness, his friend Jason Baldwin, a quiet kid whose talent for art tended toward dark subjects, and Jessie Misskelley, a 17-year-old misfit with an IQ of 73.

The arrest, trial, and conviction of the three young men known as the West Memphis Three came under national scrutiny as details of the case became public. As the West Memphis Three languished behind bars for 18 years, thousands of supporters called out for their freedom while others vehemently declared their guilt. This is a story of justice delayed and justice denied. This is the true story of the West Memphis Three murders.

A horrifying crime scene in West Memphis

As recounted in Mara Leveritt's book, Devil's Knot, a thorough search of Robin Hood Hills directed by Chief Inspector Gary W. Gitchell of the West Memphis Police Department commenced early on the morning of May 6, 1993. Despite the best efforts of the police, dozens of volunteers, a search-and-rescue team, and a helicopter dispatched from nearby Memphis, Tenn., searchers came up empty handed.

At approximately 1:30 p.m., Steve Jones, a juvenile parole officer from Crittenden County, peered over the steep bank of a water-filled ditch in the woods near the Blue Beacon truck wash. Spotting a small, black tennis shoe in the water, Jones radioed for help. Minutes later, Sgt. Mike Allen arrived on the scene. Wading into the murky water, Allen unknowingly dislodged the pale, grotesquely arched form of Micheal Moore.

With the area secured, Detective Bryn Ridge volunteered to search the ditch. Making his way through the muck on his hands and knees, Ridge soon discovered clothing twisted around sticks and thrust into the ditch's bottom. The next to be found was Stevie Branch, quickly followed by Christopher Byers. All three had been submerged face down in the mud, stripped naked, and bound with their shoelaces. Covered in wounds, all three showed signs of having been beaten. The community's worst fears were confirmed. A murderer was loose in West Memphis.

A mishandled investigation of the West Memphis murders

According to Devil's Knot author Mara Leveritt, the investigation of the murders was divided along three lines. The first being that boys were killed by someone they knew. The second postulated that they had been slain by one or more strangers. The third put forth the unusual theory that the killings were committed as a cult ritual. Unfortunately, for three teen outsiders, the West Memphis Police Department chose to focus on the cult angle to the detriment of their efforts to investigate the other two, more likely scenarios.

However, within the first crucial hours after the bodies were discovered, mistakes were made at the crime scene that negatively impacted the investigation. The bodies had been removed from the water and placed on the adjacent embankment, possibly disturbing physical evidence or otherwise contaminating the scene. Although the bodies were discovered at 1:30 p.m., investigators didn't call the coroner until 3:58 p.m. By the time the coroner arrived, fly larvae were already present in the nostrils and eyes of the victims. Lying in the open air in near 80-degree temperatures accelerated the decomposition of the bodies. Luminol tests, which reveal the hidden presence of blood, were not performed at the scene until six days later.

Also, law enforcement chose not to focus on the victims' families as the starting point of the investigation as is the norm. None of the early interviews with the parents were recorded. Investigators kept minimal notes and omitted pertinent details including criminal records.

In the shadow of the Satanic Panic

One of the keys to understanding the West Memphis Three murders is the phenomenon known as the Satanic Panic. Reaching its apex in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the Satanic Panic was a wave of paranoia rooted in the belief that Satanic cults intent on corrupting the souls of the young had infiltrated American society. Heavy metal music, role playing games like Dungeons & Dragons, and horror movies were regarded as gateways to evil. Best selling books such as Lawrence Pazder's Michelle Remembers and disgraced evangelical comedian Mike Warnke's The Satan Seller fueled the madness with tales of ritual abuse and human sacrifice.

In the Bible Belt, the Satanic Panic took hold with a vengeance. With a large population of fundamentalist Christians, the American South was particularly subject to occult paranoia. In the minds of many, the bizarre nature of the Robin Hood Hills murders could only have been committed by one of Satan's minions. On the surface, 18-year-old Damien Echols, an intelligent, but psychologically troubled teen with interests in Wicca and extreme music, fit the profile. Echols' disdain for authority, penchant for black clothes, and propensity to make shocking statements didn't help his plight.

"People probably think I'm in Satanism because ... what they don't understand they try to destroy or ridicule. ... West Memphis is pretty much like a second Salem," Echols stated in the 1996 documentary Paradise Lost: The Murders at Robin Hood Hills. "... Every crime, no matter what it is, gets blamed on Satanism."

Jessie Misskelley's problematic confessions to the murders

On the morning of June 2, 1993, Jessie Misskelley Jr., a 17-year-old high school drop out with a reported IQ of 73, was taken into custody by Detective Mike Allen. Unaware of what was to come, Allen explained that he just wanted to ask him some questions. "... (Detective Allen) told me if I knew anything, that there was a $35,000 reward, and if I could help them out, we'd get the money," said Misskelley, as quoted by Mara Leveritt in Devil's Knot.

Initially, Misskelley repeatedly denied having knowledge of the crime, aside from rumors that Damien Echols was involved. However, under pressure, leading questions, and scare tactics, Misskelley wove a contradictory story that first placed him at the crime scene as an eyewitness to the murders and then as an active participant. In this first confession, Miskelley often agreed to details suggested by the police or attributed to prior statements which he did not make.

Misskelley's coerced confession, as contradictory as it seemed to the evidence, was consistent in implicating Echols and Jason Baldwin. Misskelley, who had entered the West Memphis police station that morning with hopes of reward money he might use to purchase a new truck for his father found himself instead charged with murder and facing life plus 40 years in prison.

A later confession during the trial phase would prove equally problematic. Despite an offer of a reduced sentence, Misskelley ultimately recanted his statements and refused to testify against Echols and Baldwin.

Damien Echols was his own worst enemy

Although Damein Echols had a teenager's typical disdain for authority, he nevertheless trusted that the system would work in his favor. Certain that, under what he felt were ridiculous circumstances, Echols' confidence and, on occasion, flippant attitude during the trial was often misinterpreted as evidence of his coldness toward the victims and their families. A statement he made to the producers of Paradise Lost: The Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills did little to help his public image. "I knew from when I was real small that people were going to know who I was," Echols said in 1994. "... I kind of enjoy it because now even after I die, people are going to remember me forever. ... People in West Memphis are going to tell their kids stories. It'll be sort of like I'm the West Memphis boogeyman. Little kids will be looking under their bed — 'Damien might be under there!'"

In 1999, a more mature Echols explained the comment. "The reason I made the West Memphis boogeyman comment during the first film was because I was making light of the situation," Echols says in Paradise Lost 2: Revelations. "... I didn't even comprehend that the situation could get this serious — that it can go this far. Because I was thinking, if you haven't done anything, then they can't prove you did something you haven't actually done. That didn't make sense to me. Now, I see they can."

Vicki Hutcheson, the amateur detective of the West Memphis murders

According to Devil's Knot, a week after the discovery of the bodies, Detective Don Bray interviewed Vicki Hutcheson, a truckstop employee. Bray asked her if she knew about rumored cult activity in the community. Stating that she would ask around, Hutcheson agreed to "play detective."

Knowing that the police were already focusing on Damien Echols, Hutcheson asked her neighbor, Jessie Misskelley Jr., about the brooding teen and his occult connection. Misskelley told Hutcheson that he really didn't know much about Echols other than that he was "a weird person." Feigning a romantic interest in Echols, she asked Misskelley to arrange a meeting.

At the suggestion of the police, Hutcheson hid microphones in her home and borrowed occult books from the library to inspire Echols' interest. Nevertheless, Echols made no incriminating statements.

During Misskelley's trial, Hutcheson testified that she had attended an "an occult Satanic meeting" she referred to as an "esbat." Although she was unable to recall the exact location or anyone who attended the alleged meeting, she claimed a drunken Echols confessed to the murders.

In 2004, Vicki Hutcheson recanted her trial testimony, stating that she had lied on the stand. In her recantation, Hutcheson stated that when she asked Echols directly if he had killed "those three kids," he replied, "No. I wouldn't do something like that. I'm not stupid." She also stated that beyond the single meeting at her trailer, she had no further contact with Echols.

A dubious occult expert on the West Memphis murders

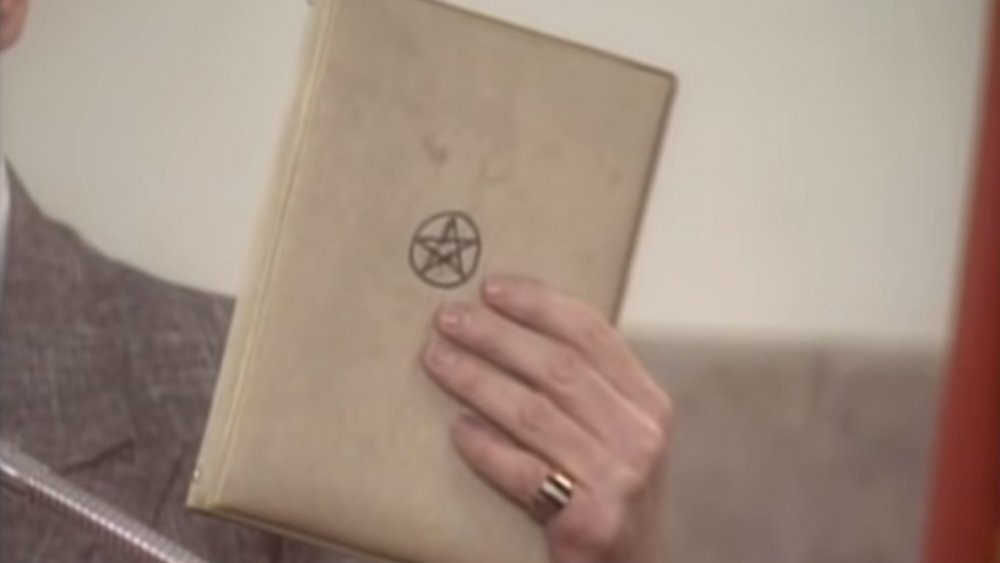

To bolster their assertions that the killings were related to occult activity — despite virtually no evidence – prosecutors brought in their own so-called expert on cult murders.

In 1994, Dr. Dale W. Griffis was a retired police officer who had embarked on a second career as a self-styled consultant on occult and cult-related crime. At the time of the West Memphis Three trial, Griffis claimed to have given seminars to 38,000 police officers all over the globe.

During the trials of Jason Baldwin and Damien Echols, Griffis drew tenuous links between circumstantial evidence, such as the killings taking place near the date of the pagan festival of Beltane. Griffis also found the devil in nearly every number associated with the crime. That there were three victims was a link to the biblical number of the beast. That the slain boys were each 8 years-old was important because eight was a "witch's number." Griffis also knew how to spot a Satanist. According to Griffis, black hair, black T-shirts, and black jeans were signs that a kid was in league with the devil.

Although Griffis' testimony was dramatic, it showed only a tenuous grasp of occult knowledge — much of it, including a reference to a cult called "Crytos," was simply made up. Defense attorneys also pointed out that Griffis' doctorate was obtained through a notorious diploma mill and had been awarded with Griffis having never attended a single class. Yet, Judge David Burnett accepted Griffis as an expert.

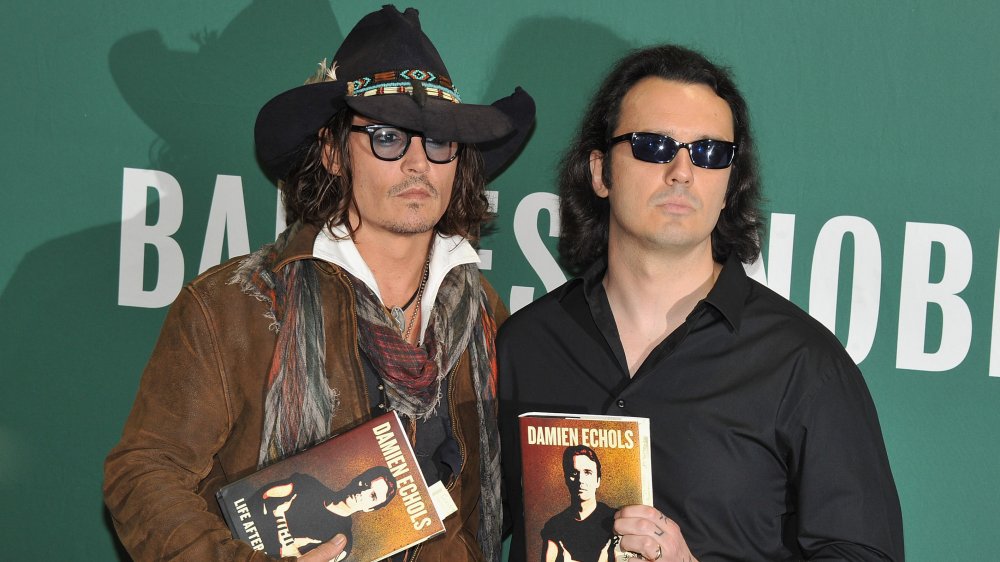

Celebrities take up the cause of the West Memphis Three murders

In 1996, HBO released the documentary film Paradise Lost: The Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills. Produced and directed by filmmakers Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky, the film and its two sequels, Paradise Lost 2: Revelations and Paradise Lost 3: Purgatory, gave audiences a unique and detailed look into the case, the accused, and the families of victims. The first film gave rise to a movement devoted to reopening the investigation in hopes of exonerating, and ultimately freeing, Jason Baldwin, Damien Echols, and Jessie Misskelley.

As the movement to free the West Memphis Three gained traction, a number of celebrities joined the cause, bringing the case under more scrutiny. Among those active in the cause were singer Eddie Vedder of the band Pearl Jam, the country music trio The Dixie Chicks, punk rock icon and poet Henry Rollins, and actor Johnny Depp.

Two of the West Memphis Three's most ardent supporters were director Peter Jackson, best known for The Lord of the Rings films, and his partner Fran Walsh. As detailed by The Hollywood Reporter in 2011, Jackson and Walsh helped fund key investigations for the West Memphis Three's defense during the last seven years of their incarceration. In 2013, Jackson and Damien Echols produced a fourth documentary about the case. Titled West of Memphis, the film, directed by Amy J. Berg, presents an overview of the West Memphis Three's 18 years in prison, the revelation of new evidence, and explores the possibility of an alternate suspect.

Alternate suspects in the West Memphis Three murders

Over the course of the initial investigation, a number of alternate suspects and scenarios came to light that were largely ignored or otherwise dismissed by authorities. Among them was a disoriented, muddy, and bleeding African-American man who stumbled into a West Memphis Bojangles restaurant men's room less than a mile from the crime scene. Although blood scrapings were taken, the West Memphis police lost the evidence.

Other possible suspects included Brian Holland and Chris Morgan, two young men from Memphis, Tenn., with a history of drug offenses. The pair abruptly fled to Oceanside, Calif., four days after the murders. At the request of West Memphis authorities, the two were picked up and questioned by Oceanside police. Polygraph tests revealed deception in the answers of both men in regard to the crimes. After hours of questioning, a frustrated Morgan blurted out that he had been hospitalized for drug and alcohol abuse and might have committed the murders. Blood and urine samples from both men were collected and sent to the West Memphis Police Department. No explanation has yet been given as to why such a seemingly important lead was dropped.

New evidence in the West Memphis Three murders

In 2007, new DNA and physical evidence arose that seemed to further distance the West Memphis Three from the murders. As reported by the Arkansas Times, examination of the shoe laces used to bind Michael Moore contained hair "not inconsistent" with that of Stevie Branch's stepfather, Terry Hobbs.

Pam Hobbs divorced Terry Hobbs in 2004 and has reversed her position on the West Memphis Three's guilt. She has since expressed her belief that her ex-husband was involved in the murders, citing the discovery of her son's favorite pocket knife in Terry Hobbs' belongings. Inconsistencies in Terry Hobbs' alibi, as well as revelations about subsequent violent acts, have also led many to believe that he may be the actual killer.

Other details that have come to light include that many wounds on the slain children, originally attributed to human bites and/or a serrated blade, were the result of animals feeding on the bodies.

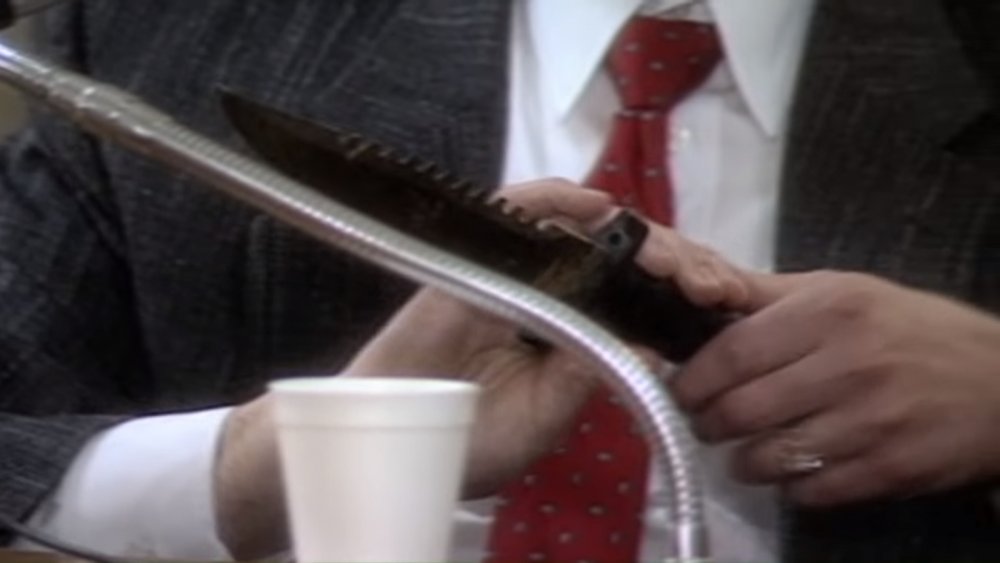

One of the prosecution's key pieces of evidence linking Jason Baldwin to the crime — a survival knife with a serrated edge recovered from a lake behind his home — has also come under scrutiny. The knife was thrown into the lake by Baldwin's mother a year before the murders.

To date, no DNA evidence from the crime scene can be linked to Damien Echols, Baldwin, or Jessie Misskelley.

The price of freedom for the West Memphis Three

With their 2007 request for a new trial rejected, time was running out for the West Memphis Three. However, in 2010, a series of rapidly unfolding developments turned the tide for Damien Echols, Jason Baldwin and Jessie Misskelley. In November, Judge David Burnett, who had presided over the trial, was elected to the state senate. Replacing Burnett was Circuit Court Judge David Laser. Under order of the Arkansas Supreme Court, there were to be new evidentiary hearings in the case.

On Aug. 11, 2011, the West Memphis Three entered the courtroom for the final time. In a last ditch effort, they entered an Alford Plea, a complex and seldom used legal maneuver that would see them plead guilty while still asserting their innocence. Also part of the plea was the provision that the three could not sue the state. After 18 years in prison, the West Memphis Three were finally free, but not exonerated.

The enduring mystery of the West Memphis murders

Over two decades after the murders, what really happened to Stevie Branch, Christopher Byers, and Michael Moore on the evening of May 5, 1993, remains a mystery. Although the Alford Plea set the West Memphis Three free, they are, at least in the eyes of the law, guilty, and therefore, the state of Arkansas is under no obligation to continue investigating the crimes at this time.

In the years since the trial, John Mark Byers, adoptive father of Christopher Byers, and Pamela Hobbs, mother of Stevie Branch, became vocal supporters of the West Memphis Three. Terry Hobbs, Todd Moore, and Dana Moore still maintain that Damien Echols, Jason Baldwin, and Jessie Misskelley murdered their sons.

Echols is an author and mystic living New York with his wife, architect Lorri Davis. Baldwin is the co-founder of the legal advocacy organization Proclaim Justice. Misskelley returned to life in West Memphis.