The Messed Up Truth About The Soviet Labor Camps

It's common knowledge that the Russian Gulag was a prison. Less well-known is that it was actually a system of prisons, specifically designed for hard labor. The word "Gulag" is an acronym, Glavnoe Upravlenie ispravitel'no-trudovykh LAGerei, which roughly translates to "Main Administration of Corrective Labor Camps."

The labor camps were there to correct behavior and punish infractions but also to be of practical benefit to the Soviet nation. The people sentenced to camps lived in horrific conditions and were sent there for often morally outrageous and legally dubious reasons. Often considered a special aberration of Stalin's dictatorship, the camps predated him and continued after him, too.

For most of the 20th century, the world was unaware of the inhumane extent of Soviet labor camps and what the people within them had to endure. Now, three decades after the USSR, the methods and magnitude of the labor camps are being revealed.

Gulags are an ancient Russian tradition

Prisons are ancient technology. Practically as long as we've had buildings, we've had prisons of some sort, oftentimes as far from the rest of civilization as possible. Within ten years of Russia's claim over Siberia, they began using it as a prison. And they've never really stopped.

One of the defining attributes of prison, one considered necessary by many, is discomfort. Well, Siberia is uncomfortable. And far away. Czars wanting to punish people had a vast, empty area, thousands of miles away, to dump them into. As Dr. Helen Hundley, professor of history at the University of Wichita, states: "From the very beginning of the Russian control of Siberia it was used for exile." Problematic peasants, unruly serfs, and, after the Great Schism in the Russian Orthodox Church in the 17th century, members of now-heretical belief systems were sent east en masse.

Impertinent peasants could be exiled, along with their entire families. Political rivals, petty thieves, adulterers: The list of offenses deemed worthy of exile is long and extremely arbitrary. In fact, when a riot erupted in the small village of Uglich during the 16th century, not only were the rioters sentenced to Siberian exile, but so was the town bell "for its role in summoning the towns people to the riot." It was flogged in public before being sent off, and it wasn't returned until 1892.

Russia used labor camps to colonize Siberia

Today, Russia is the largest country on the planet, encompassing a land area almost as large as the entire surface of Pluto, but it didn't start that way. Since the collapse of the Mongol Golden Horde in the 15th century, Russia's leaders spent the next few centuries adding territory the way every ambitious empire does: colonization. While Russian colonization would eventually stretch all the way to the Americas, they started in Asia. And since people were generally reluctant to move to Siberia, incentives were needed. Incentives like a prison sentence.

According to a 2018 article in the International Review of Social History, Russia "was interested not only in the punishment of criminals, but also in the concentration of coerced convict workers in places that would benefit the state." Russia needed dockyards to build a navy, and imported peasants provided the work. Russia's increasingly ambitious military and civil plans required financing, and Siberia's silver mines were filled with exiled laborers. Just in the 19th century, over 800,000 Russians were sent to Siberia.

The end of the 19th century saw a wave of reforms in Russia, including of serfdom, peasantry, and the penal system, as well as economically. With the construction of the Trans-Siberian Railway, and the relative freedom to move within the Empire, Russian peasants actually chose to move east. Enticed by plentiful, arable, available land and jobs in many industries, some three million Russians emigrated to Siberia between 1895 and 1910.

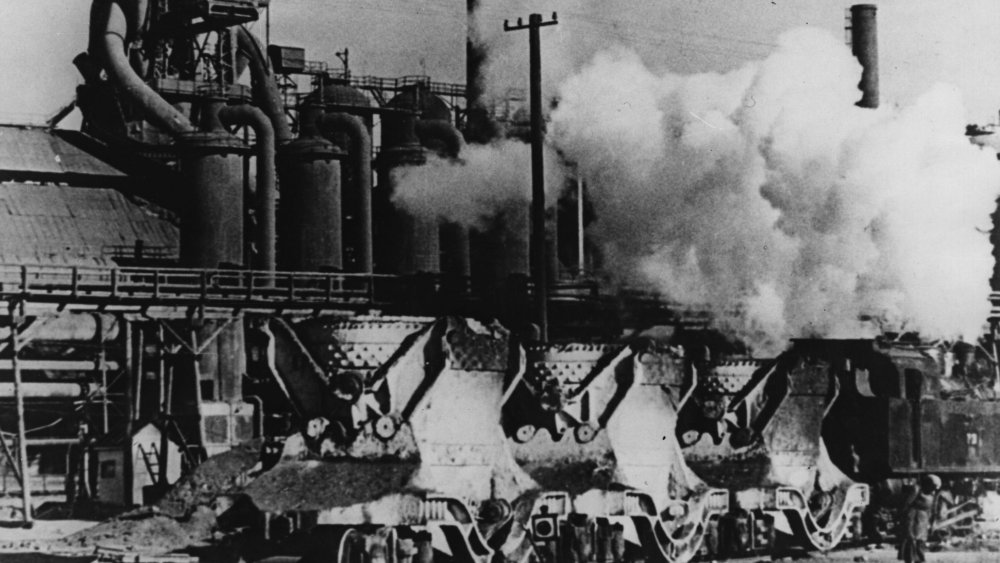

Labor camps were key to Stalin's industrialization

The Romanovs had been trying to modernize Russia since the mid-19th century. After the 1917 revolution, Russia's new Communist leaders continued to work on transforming a nation of peasant farmers into a manufacturing center able to compete with Britain, France, USA, and Germany. When Joseph Stalin seized power, determined to industrialize the Soviet Union, he revived an old czarist tradition: slave labor.

Stalin's first Five-Year Plan was predicated on wildly unrealistic expectations, and as the Siberian camps had been reopened back in 1919, Stalin saw no reason to let that much labor go to waste. As Marxist magazine The New International noted in 1947, "Slave labor, then, was the Stalinist answer to the high level of productivity of the western capitalist powers." According to Soviet documents at the Open Society Archives, "the number of prisoners incarcerated in labor camps increased 23 fold" during the first Five-Year Plan.

Millions of prisoners were used as Stalin's invisible labor force, working on huge projects in dangerous conditions with little safety and no dignity. Over 100,000 prisoners, for instance, using little more than pickaxes and wheelbarrows, dug out a 227-kilometer-long canal in just 20 months. Tens of thousands died. For Stalin, the Gulags were, as Hoover Institute scholar Paul Gregory explains, "the exploration and industrial colonization of remote resource-rich regions at a low cost of society's resources."

Siberia is unreasonably cold

While not all camps were located in Siberia, most of them were, for a number of reasons. First, the distance between Moscow and Siberia is over 2,200 miles, a five-hour flight or a 15-hour train ride. Troublemakers sent east would have a hard time making it back. Siberia was, and still is, mostly empty of people, so there was, and still is, plenty of opportunity for construction and mining projects — a perfect place for slave labor. Siberia is also its own prison warden: If the work doesn't kill you, the cold will.

Siberia is cold. Unreasonably cold. It is, in fact, the coldest place on the planet in which human beings actually live full-time. In fairness, much of Siberia sits above the Arctic Circle, but that doesn't seem to matter too much. The tiny village of Oymyakon, population around 500 frozen Russians, sits well below the Arctic Circle but still regularly experiences temperatures in the -80s Fahrenheit. In 1933, according to Gizmodo, Oymyakon recorded the coldest temperature ever seen outside of Antarctica, a frightening -90 °F.

Ukrainian priest and historian Father Ivan Lebedovych wrote of the Gulags: "Nothing can be more frightening and dangerous than a Siberian blizzard [...] Wolves perish, and dogs can no longer sniff out the freshest trails." Guards didn't much care if the prisoners were outside: Cold killed as efficiently as a bullet but with less paperwork.

Really, Siberia wants to kill you

Siberia is so big that if it was its own country, it would still be the largest on Earth, and it's filled with marshes, forests, and mountains. It took two Polish prisoners more than three months to travel home when they escaped in 1945, and they were lucky to train-hop a few times, as their nephew told The Weather Channel. Besides the insane distances, Arctic climate, and armed guards, fleeing prisoners have to contend with some frightening creatures.

Russia is often symbolized by the bear, and for good reason. Black bears, brown bears, and even polar bears prowl Siberia. And when they're hungry, Siberian bears have been known to attack actual villages, as Russian news service Rusbalt reported a group of 30 brown and black bears did in 2015. Siberia hosts not only gray wolves but also the Amur tiger, one of Earth's biggest cats. Siberian boars are known as one of the most dangerous animals in the region and, as reported by Russia Beyond, are prone to charging at cars.

For some reason, Siberia is also home to a species of venomous viper. Then there are the disease-carrying ticks, mobile home to encephalitis and Lyme disease. And no natural horror could be complete without arachnids, which Siberia provides in the form of the venomous karakurt.

The Two Terrors

The 1917 Bolshevik revolution was an ideological one and, as such, had no shortage of enemies — real and imagined. The early Soviet Union was a tumultuous period. Competing factions murdered each other with abandon as the new state settled into itself.

By 1919, the camps were open. Within four years, tens to hundreds of thousands of people had been executed, and many times more sent east, in an episode called the Red Terror. Time magazine quotes a Soviet secret police officer's explanation: "We are not waging war against individual persons. We are exterminating the bourgeoisie as a class ... In this lies the significance and essence of the Red Terror." Murder and imprisonment became an unfortunate model for the Soviet state, reaching apotheosis just ten years later.

According to historian James Harris, Stalin and the Bolsheviks knew their history. Most revolutions had failed, and they didn't want a repeat of the French Revolution or the 1848 Spring of Nations. Fascism was rising in Europe. The USSR was starving and dysfunctional, and the politburo was surrounded by enemies. To combat the bourgeoisie, capitalists, and counter-revolutionaries, in the mid-1930s, the Communist Party embarked on a sustained two-year spree of terror known as Stalin's Great Purge. Over half a million Russians were executed without trial or any legal process, and over a million more were sent to the gulags, including most of the Bolsheviks who participated in the Red Terror.

Almost anything could get you sent you to a camp

The criminal code of the USSR lists 14 violations that are less well-defined legal definitions and more "trust us, you did something." You could be Siberia-bound for committing "counterrevolutionary sabotage" by simply showing up late for work. The capriciousness of Soviet criminal sentencing could be unfair to the point that even a Disney villain would look askance at Communist justice.

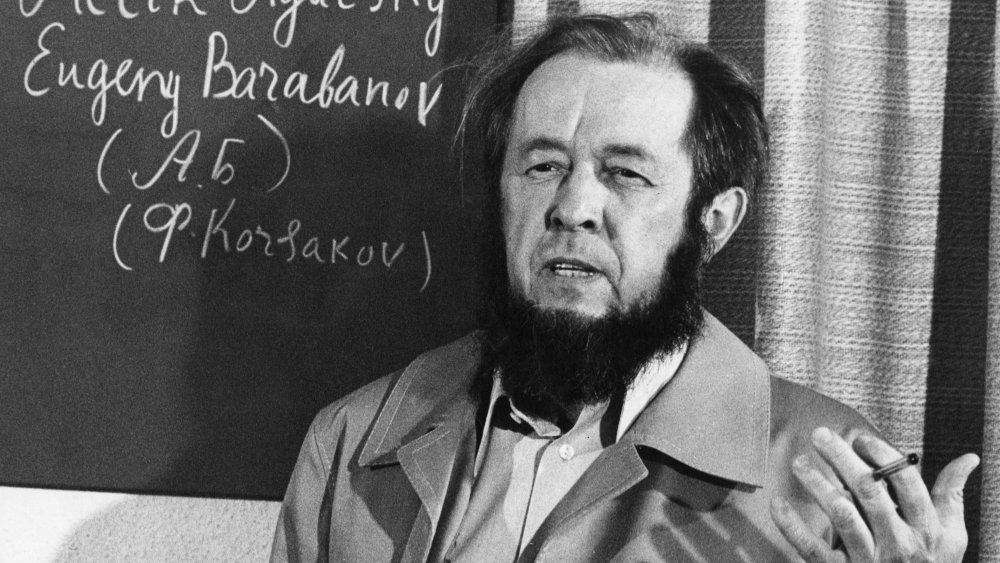

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (pictured above), author of the famous Gulag Archipelago, was sentenced to eight years for writing negatively about Stalin in a private letter. Expressing anything in any medium that could in any way be interpreted as disparaging to Stalin, the Soviet state, or anyone associated with the state (like, say, your boss), could get you sentenced for "subversion, or weakening of Soviet authority" or "other counterrevolutionary crimes."

Love could be illegal in the USSR as well. Being gay was a literal crime in the Soviet Union, says Oxford University professor of Modern Russian History Dan Healey, explaining that under the Soviet penal code: "Sexual relations between men were punishable by imprisonment of between three and five years." Lyudmila Khachatryan was 18 when she was arrested for being married to a Yugoslavian, which, as a fellow Communist nation, shouldn't have been an issue but became a problem when Stalin got a hate-crush on that country's leader. She was raped, imprisoned, and sentenced without trial to eight years in a Siberian labor camp.

Soviet labor camps were hell

That prison is awful shouldn't surprise, but Stalin's labor camps were intended to be torturous. Historian Anne Applebaum spent years researching the Soviet archives and says that the "prison and camp regimes, which were dictated in minute detail by Moscow, were openly designed to humiliate prisoners." Prisoners were even forbidden from using the word "comrade." She recounts a 1992 interview with a former camp commander: "If we had sent civilians, we would first have had to build houses for them to live in. With prisoners it is easy — all you need is a barrack, a stove with a chimney, and they survive."

And survive is all most people could do. The camps were overcrowded, stank, and were poorly insulated for the climate. The prisoners weren't given enough food, clothing, medicine, or wood for the fire, and violence was endemic as they fought for survival. Added to this is a landscape evolved to kill you and guards who, even if they don't try to kill you, don't care if something else does. "All the while," says the Gulag Museum, "prisoners were watched by informers — fellow prisoners always looking for some misstep to report to Gulag authorities."

The conditions were so terrible that Soviet inspectors regularly reported on the bad food, inadequate health care, and diseases rampant in many camps ... but only because it was hampering production quotas. They were labor camps, after all.

Labor camp husbands

On the one hand, Soviet women enjoyed a greater degree of legal equality than most of the world in the 20th century. They had greater opportunity for education and employment, and the USSR integrated its armed forces far earlier than most nations. They even sent the first woman into space. On the other hand, Russia was still a pretty traditionally patriarchal society, and women faced cultural barriers and unique challenges, especially in prison.

The disparity between legal equality and physical reality for Russian women was violently pronounced in the labor camps. Women were frequently subject to special degradation from fellow prisoners as well as the guards. In her book, Gulag Voices, Anne Applebaum described the horrific everyday cruelty that women endured as well as organized mass punishments, including group gang rape.

Many women sought protection and survival in the only way they could, by exchanging their bodies for better treatment, more food, or medicine. Some women even took "Gulag husbands." The consequences could sometimes be even more tragic, as contraception was not provided by what passed for camp medical providers. If an inmate got pregnant, she was not given lighter duty or any relief from her work. Should a woman carry to term, says the Gulag Museum, "Gulag officials took babies from their mothers and placed them in special orphanages. Often these mothers were never able to find their children after leaving the camps."

Prisoners were sent to war

The ultimate purpose of the camps was for the inmates to be of use to the state. From mining to construction to agriculture, prisoners were placed where they'd contribute to the Soviet Union and/or die trying. Hitler's 1941 invasion of Russia soon turned the western Soviet Union into a charnel house, in need of bodies that prisoners would provide.

Germany had plunged deep into the USSR, capturing Ukraine, Belorussia, the Baltics, and more. In the now-infamous Order 227, Stalin reproached the Soviet army, "that means that we have lost many people, bread, metals, factories, and plants." As the Soviet army retreated in the face of the Nazis, Stalin issued a no-retreat policy. "Not a single step back!" he declared. Among the ways commanders were ordered to encourage courage was with "penal battalions" of 800 people "who have broken discipline due to cowardice or instability [...] These battalions should be put on the more difficult sections of a Front, thus giving them an opportunity to redeem their crimes against the Motherland by blood."

Prisoners sentenced to labor camps were diverted to the front, where, along with anyone suspected of even thinking about retreat, they advanced before "blocking units" made of regular soldiers ordered to shoot the penal battalions down if they refused to fight. Oxford historian Catherine Merridale, in her book Ivan's War, stated that at least 422,700 men served in the Soviet penal battalions.

There were children in the labor camps

Since finding day care for political prisoners is such a hassle, women arrested at home were frequently shipped to the camps with their children. The children would be placed in what we can euphemistically call "nurseries," along with the children whose mothers arrived pregnant or were unfortunate enough to have conceived after getting there. It shouldn't surprise anyone that the nurseries were as cruel as the rest of the place.

Gulag children were underfed and abused, neglected to the point that survivors suffered severe permanent injuries and psychological trauma. Leeds historian Kelly Hignett described the account of one survivor's memories of "how shocked she was on discovering that many older children in one camp nursery would not even speak, communicating instead via inarticulate howls." Infant mortality was atmospherically high, and violence of all kinds was routine.

In 1935, the law was changed, and children from the age of 12 could be sentenced as adults, including to a stint in the labor camps. According to the 2010 book Children of the Gulag, of the nearly 20 million people sentenced to prison labor in the 1930s, about 40 percent were children or teenagers. Legions of homeless street kids were exiled and became prey for older, actual criminals. As the Red Army pushed the Nazis west, the children of Soviet citizens trapped behind German lines suspected of disloyalty often were deported to Siberia as well.

Over one million people died in the labor camps

The Soviet penal labor system was a sprawling network of almost 500 camps throughout the USSR. Per Britannica, the title of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn's The Gulag Archipelago compares the system to a chain of islands, disconnected from each other and from Russia itself, the inhabitants left to fend for themselves in a hostile, remote environment. The people sent there weren't part of society and weren't supposed to be, so little care was paid to keeping track of them.

According to Solzhenitsyn, "some forty to fifty million people served long sentences in the Archipelago." As the USSR was collapsing in the late 1980s, the Soviet archives were opened up, and they revealed an official government tally of ten million souls sent to Siberian camps between 1934 and 1947 alone.

It is estimated that between 1.2 and 1.7 million people died in the Soviet labor camps between 1918 and 1956. The camps fulfilled their purpose, however, as described in the journal Mortality, "for some 50 years after the height of Stalin's purges, Gulag survivors risked severe punishment if they discussed their experiences." It is likely that the precise number of people sent to and who died in the camps will never be known.