The True Story Of How Britain Destroyed Their Files On Colonialism

The British held onto a deception for an incredibly long time and had the Kenyan people not won the right to sue the British government for crimes committed during the colonial regime, it's unclear if the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) would've ever revealed all the evidence they purposefully withheld.

And it's not like they were unaware of their crimes and what they were sitting on. In 1999, a note was made on a document literally underlining the importance of keeping the documents concealed.

Had the court case not proceeded, who knows when these documents would have surfaced. As recently as 1999, an FCO official had made a note on a document stressing with three underlines that the migrated documents were to be kept a secret. In 2017, the British government admitted that it "lost" thousands of additional documents regarding the Falklands war.

Documents were destroyed in literal bonfires, dropped into the ocean, or separated and transported to London with the explicit purpose of being kept out of the hands of post-independence governments. Often referred to as "Operation Legacy," this attempt to destroy and withhold evidence of the brutal crimes committed by colonial regimes is truly in line with colonialism's legacy. This is the true story of how Britain destroyed their files on colonialism.

A quick overview of Britain's colonialism

For almost 300 years, British ships transported over 3 million enslaved people away from their homes on the African continent. But the British invaders kept to the coasts of Africa, and the only colonized areas under British rule were Cape Colony and the Colony of Natal, located in what is now South Africa. Before the Berlin Conference, 80% of Africa remained under local and traditional control.

According to Black Past, lines weren't drawn during the conference itself, except around the Congo Free State, which was allocated by the European powers to King Leopold II of Belgium with the stipulation that it be "an area of Free Trade for all Europeans in Africa."

The Berlin Conference was the initiation of formal colonization. There were neither African people at the conference nor anyone speaking on their behalf. And this was entirely by design. According to Al Jazeera, when the Sultan of Zanzibar had attempted to get a seat at the conference, he was laughed off by the British. The European powers were admittedly uninterested in the sovereignty of African nations and were focused on African resources in the interests of "commercial and industrial nations."

On Feb. 19, 1885, the Lagos Observer reported that "The world had, perhaps never witnessed a robbery on so large a scale. Africa is helpless to prevent it. It is on the record that 'Christian” business can only end, at no distant date, in the annihilation of the natives."

Fighting for independence from Britain

Between 1880 and 1900, Britain ended up colonizing 30% of Africa's population. But independence movements were close behind, with Egypt's declaration of independence in 1922.

According to CVCE, a number of the British colonies were some of the first to declare independence. Ghana achieved independence in 1957, Nigeria in 1960, and Kenya in 1963, among many others. Tragically, Kenya's independence came "after a brutal crackdown on Mau Mau fighters who battled colonial rule from 1952 to 1960." And for some colonies, the fight against colonial rule continues into 2020.

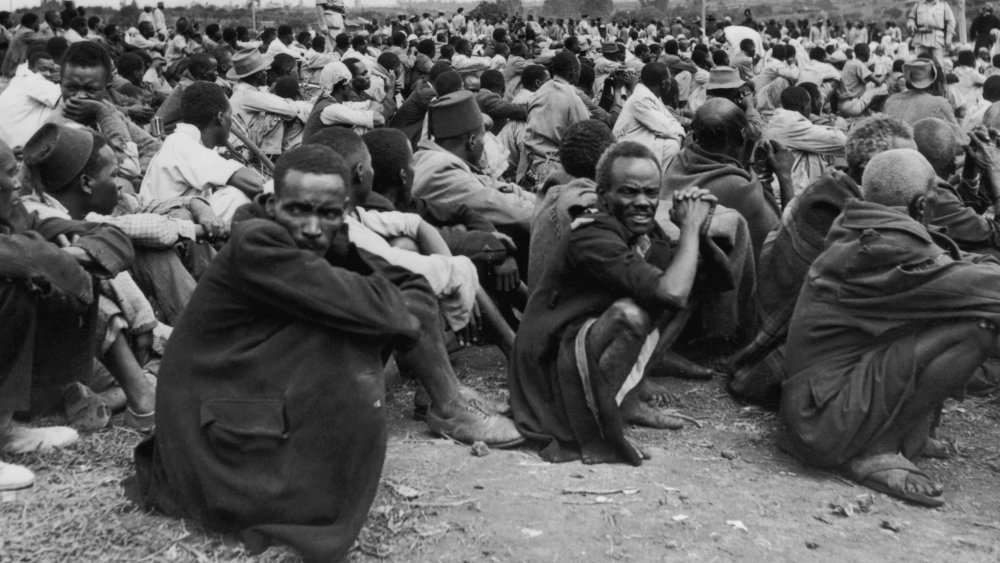

According to Black Past, the Mau Mau Uprising was started by Kikuyu people who formed the Kenya Land and Freedom Army (KLFA) and revolted against the lack of political rule and the loss of land to white settlers. During the eight years of the war, over 20,000 KLFA and 1,800 African civilians were killed. Two hundred British soldiers and police and 32 white settlers also numbered amongst the casualties.

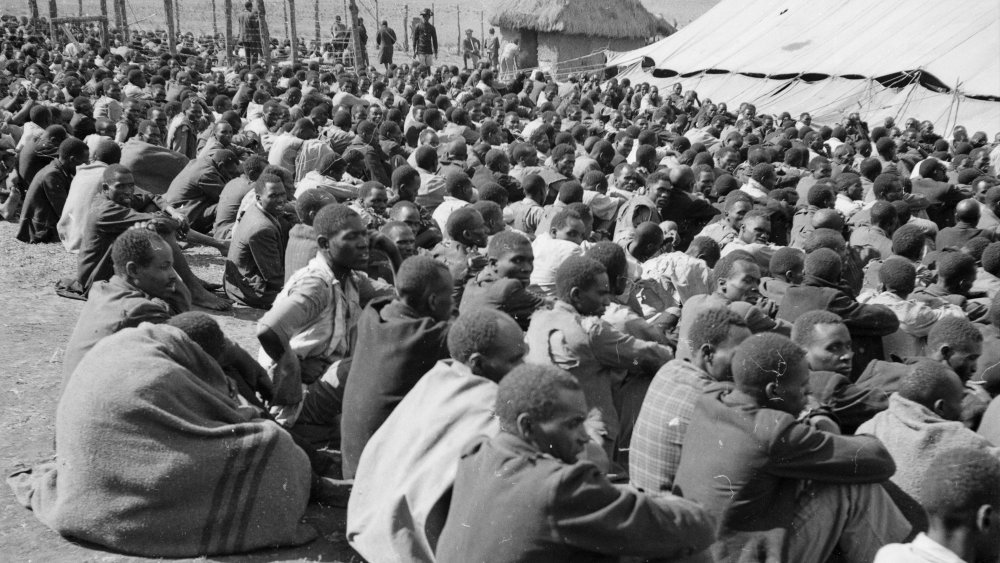

In response to the uprising, the British constructed several detention camps for suspected KLFA and their supporters. Over 150,000 people were kept in these concentration camps and countless were tortured by the British officers. While there were thousands of documents that detailed these atrocities, during the independence movements the British government set out to destroy and commandeer any and all documents that detailed "evidence of systematic torture, murder, and other crimes."

Britain gives instructions for a purge

As colonies started freeing themselves from colonial rule, the British were anxious to destroy any evidence that might negatively implicate them before it fell into the hands of the former colonies. According to The Guardian, Colonial Secretary Iain Macleod issued instructions in 1961 that "post-independence governments should not be handed any material that 'might embarrass Her Majesty's government ... members of the police, military forces, public servants, or others.'"

And this was not the first time such instructions had been issued. According to "Operation Legacy," by Shohei Sato, similar instructions were issued on May 29, 1956, in the Gold Coast, now known as Ghana. Roughly one year before independence, a committee was set up by the Governor's Office of the Gold Coast in charge of separating the records that were "to be handed over to the new state after independence."

While some documents were separated in order to be taken back to Britain, thousands of records were destroyed. Records were also separated and destroyed in North Borneo, now known as Malaysia, in July 1963.

According to Post-War British Literature and the 'End of Empire' by Matthew Whittle, the British gave very specific instructions as to how the documents were to be destroyed. Usage of bonfire came with the stipulation that the records be "reduced to ash and the ashes broken up." If taken out to sea, the records were to be "packed in weighted crates and dumped in very deep and current-free water at maximum practicable distance from the coast."

An elaborate British classification system

Not every document was meant to be destroyed, and the British created an elaborate classification system in order to determine what file went where. There were variations amongst the colonies but most employed a consistent system of categories.

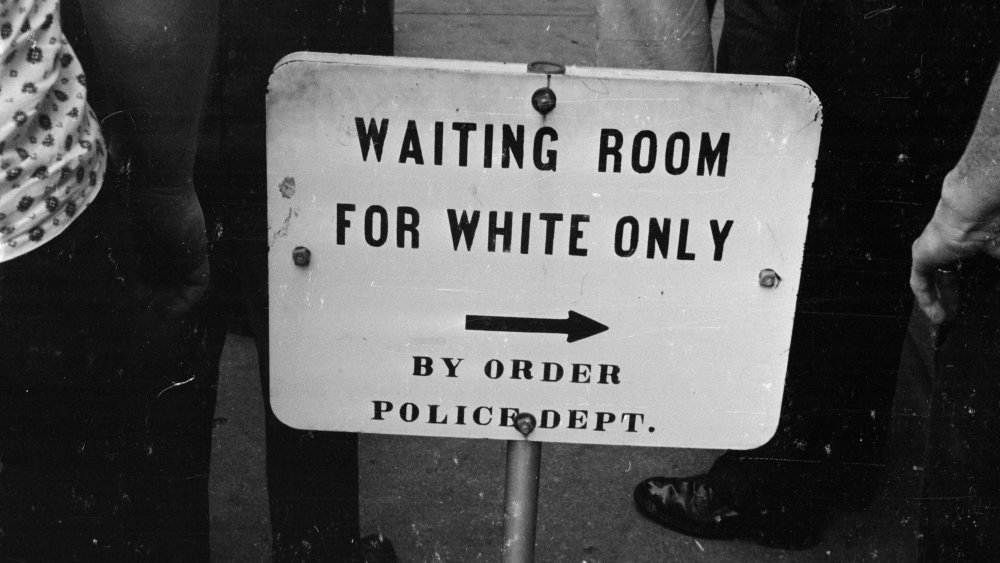

According to "Legacies of British Colonial Violence" by Aoife Duffy, a memo was circulated in Uganda in February 1961 "with the instruction that official papers should be withdrawn ('either be destroyed or passed to a higher office') and made inaccessible to 'unofficial' or 'unauthorized officers.'" Papers in Uganda "which might be interpreted as showing racial discrimination against Africans" were withdrawn with the designation DG, standing for "Deputy Governor."

In Kenya, files stamped with a W for "Watch" had the same fate as DG files. According to The Guardian, the files were stamped with a red letter W and were meant to leave no trace behind. One instruction wrote, "Indeed, the very existence of the watch series, though it may be guessed at, should never be revealed."

Files could also be categorized as "Legacy" files, which consisted of "all those other papers which may safely and appropriately be seen in the course of duty by persons who may not fit the definition of 'authorised' officers'." In this case, an "authorized" officer was someone who was a "British subject of European descent." According to New Dark Age, by James Bridle, some even came with warnings, such as "This file to be processed and received only by a male clerical officer."

Britain's dummy files

When single W files were removed, a "dummy" file was put in its stead. Dummy files were essentially sanitized versions of the document, but it was crucial that post-independence governments didn't know that any sort of "cleaning process" had occurred.

According to The Guardian, when too many "dummy" files would've had to be made, "the documents were to be removed en masse," with nothing left in their stead, but nothing that would refer back to the gap.

And according to News Ghana, the British especially wanted to make sure that Macleod's instructions remained a secret, for "there is of course the risk of embarrassment should the circular be compromised." Officials participating in the purge were told to be sure that their W stamps were kept in a safe place.

While some of the W files ended up at Hanslope Park in England — collected from 37 different former colonies — in some colonies, such as Kenya, officials were told that an "emphasis is placed upon destruction." So, ultimately, what remains at Hanslope Park is what the British considered to be "least embarrassing."

Britain gives insincere justifications

The British Empire offered paltry excuses for what they were doing. According to "Operation Legacy," by Shohei Sato, in Malaysia, the British claimed that the disposal of documents is "in accord with the usual policy by which the secret records of one Government are not left for the use of its successors ... and the opportunity is being taken to destroy a number of files which are no longer of any importance or value."

But both of these claims were false and insincere. The document purge of the British differed drastically from a typical document removal that happened during a cabinet change. And many of the documents being confiscated or destroyed in this scenario were done so because they were so valuable and sensitive. The British also claimed that they wanted to protect future African leaders from embarrassment as well and sought to remove "papers likely to be embarrassing to African leaders, officials, and politicians in the future."

The documents that did survive the various purges didn't even come to light until 2011, when the FCO was forced to admit that it had been lying about its unawareness of colonial documents pertaining to the Mau Mau Uprising. And not only was the FCO lying about their knowledge of the vast numbers of documents, they were also illegally withholding them, since the Public Records Act of 1958 states that documents are to be released to the National Archives after 30 years.

For European eyes only

According to "Operation Legacy," many of the classifications were less of a "'security grading,' [and] more of a racial indication." Knowledge of the operation was only to be known to those who were not only British, but also "of European descent."

People's nationality was also considered. A letter from 1961 notes that "On no account should any 'personal' communication be shown to any African, to a person of another nationality other than British, or to a non-official."

According to The Observer, O.E. De Souza is one such example. On March 3, 1961, R.E. Stone wrote a letter requesting for De Souza, originally of Portuguese nationality from Goa, India, to become an authorized officer. While De Souza wasn't a naturalized British person, she was married to one and had signed a "Declaration of Acquisition of British Nationality." But although she was considered loyal and competent, the request was denied due to her non-European origin.

The British justified this with the claim that they were looking out for their own interests in expectation of a time when they wouldn't be there to protect them. "If it is known in the future that [some people] have had access to 'European eyes only' material they may quite likely be subjected to pressure to reveal it which they will find hard to resist when we are no longer here."

Suing Britain for compensation

This entire operation wouldn't come to light until 2011, when Wambugu Wa Nyingi, Paulo Muoka Nzili, Ndiku Mutwiwa Mutua and Jane Muthoni Mara won the right to sue the British government for the torture they experienced by colonial officials and soldiers during the Mau Mau Uprising. Unfortunately, according to The World, another one of the original claimants, Susan Ciong'ombe Ngondi, died of old age while waiting for that court decision, and only Nzili, Nyingi and Mara lived to see the final decision in 2013.

In the end, while "Britain still did not accept it was legally liable for the actions of what was a colonial administration," reported the BBC, the British government agreed to a payment of £19.9 million to 5,228 victims.

Although the FCO previously denied having any documents relevant to the crimes when the lawsuit was first brought forth in 2009, in 2011, the FCO admitted that it was illegally withholding some relevant files at Hanslope Park. Soon after, they confessed to actually withholding tens of thousands of files. And according to The Guardian, at least 13 boxes of Kenya files are still "missing."

Had the court case not proceeded, who knows when these documents would have surfaced. As recently as 1999, an FCO official had made a note on a document stressing with three underlines that the migrated documents were to be kept a secret.

Britain's migrated archives

When the FCO initially yielded in 2011, they revealed 1,500 files known as the "migrated archives," all of which were taken out of Kenya during the time of decolonization. But then a few months later, the FCO claimed that they found over 8,000 more files that pertained to 37 different colonies. According to Vice, as of 2014, the FCO has confessed to possessing over 20,000 files.

Unfortunately, all these files are ultimately just a tiny fraction of all the documents from Britain's colonialist endeavors. According to New Dark Age, by James Bridle, "accompanying the remaining files – most of which have still not been released – are thousands of 'destruction certificates': records of absences that attest to a comprehensive programme of obfuscation and erasure."

Up until 1993, at least 170 boxes of files were kept in London, taking up roughly 79 feet of shelf space. But in 1992, worried that "a Labour victory in the upcoming general election would lead to a new period of openness and disclosure," thousands of documents were moved to Hanslope Park. During this transfer, several files went missing and have not been seen or heard from since.

It's estimated that there are at least 1.2 million documents, but at this point who knows what else the FCO is keeping to themselves.

Britain testing poison gas in Botswana

One of the things that came to light as a result of the migrated archives being properly opened and cataloged, as they should've been according to law, was Britain's plan to test poison gas in Botswana.

According to Botswana Online News, British officials had initially wanted to test a type of poison gas within the Union of South Africa, but the Pretoria government told the British that there were no suitable places. The British ended up deciding on an area south of Nata lake, and in July 1943, a British colonial official responded to the U.K. ministry, "Your instructions have been noted and your letter destroyed by burning."

But by November, the testing area was still up in the area and with the rainy season close, the plan was postponed until the next year. However, this is the last note in the file, so it's unclear whether or not the plan ever went ahead as planned.

Britain's concentration camps in Kenya

When the British detained thousands of people during the Mau Mau uprising, at least three departments kept files on every one of the detainees. But when historian Caroline Elkins was looking for the files, an estimated 240,000 for the 80,000 detainees, she only found several hundred.

According to Al Jazeera, the Mau Mau Uprising was started by the KLFA rebels, but the British were quick to start a series of mass arrests against Kenyans. Anyone vaguely suspected of associating with the KLFA was arrested and taken to be tortured and/or detained in concentration camps.

As the fighting continued between the colonial government and the KLFA, the British sometimes moved large groups of people into "protected villages" that were surrounded by armed guards and barbed wire. Upwards of 300,000 Kenyans are thought to have been kept in concentration camps, and over 1 million were also kept in "protected villages."

After KLFA leader Dedan Kimathi was captured, sentenced to death, and executed in 1957, it took the British another three years to lift the state of emergency they had imposed during the uprising.

Still no justice for the Batang Kali massacre

Thousands of documents were also destroyed to cover up the atrocities that the British committed in the colony of Malaya. One such atrocity was the Batang Kali massacre.

According to The Guardian, in 1948, plantation workers were murdered by the Scots Guards and after mutilating the bodies, the Scots Guards burned the village of Batang Kali to the ground.

In 1993, the Malaysian police contacted Interpol and scheduled a trip to the United Kingdom in order to interview the soldiers involved in the shooting. But the FCO stepped in and pressured Malaysia's high commissioner into putting a stop to the visit.

The British government still has not offered any reparations or apologized for the massacre. And unlike the case of those tortured in the Mau Mau detention camps, no one who survived the Batang Kali massacre is still alive today, making prosecution a little more difficult. This was seen in 2018, when an application for an investigation by Loh Ah Choi, Chang Koon Ying, Lim Ah Yin, and the families of 24 people who died at Batang Kali was rejected by the European Court of Human Rights.