The Tragic Story Of The Biggest Maritime Disaster In History

The worst maritime disaster in history was the sinking of the Titanic. Except that it wasn't, we just think it was because of Leonardo DiCaprio and Kate Winslet. And by the way, Jack could have totally fit on that door. Anyway, more than 1,500 people died when the Titanic sunk in the icy waters of the north Atlantic, but that doesn't even come close to the number of people who died during the actual worst maritime disaster in history. In fact the actual worst maritime disaster in history makes the Titanic look like a model of health and safety by comparison. And yet, it wouldn't be super surprising if you'd never even heard of the shipwreck that killed more than 9,000 people, including nearly 4,500 children.

Why is the sinking of the Wilhelm Gustloff such an obscure piece of history? Well, it happened at the end of World War II, when the world was already pretty weary of all the casualties. And it also happened to the enemy — or at least to enemy civilians and their families (mostly) — which means the media on either side wasn't exactly eager to tell the story. We're going to tell it here, though. Here's the horrible, horrible truth of the sinking of the Wilhelm Gustloff.

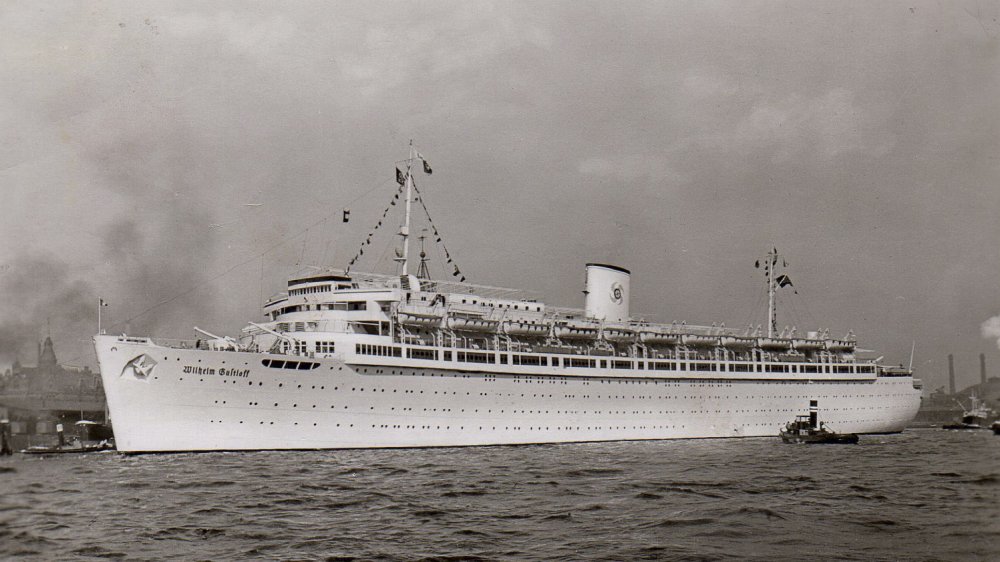

Before it was a shipwreck, the Wilhelm Gustloff was a luxury liner

There are actually a remarkable number of similarities between the Wilhelm Gustloff and the Titanic. Both ships were what you might call opulent. According to Smithsonian, when the Gustloff was first christened in 1937, it was a luxury liner with a singular mission: giving "vacationing Nazis ocean going luxury." During its short career as a cruise ship, the Gustloff went on 60 different voyages and hosted a total of around 80,000 passengers. Winter voyages took passengers to Italy or Portugal and the islands of Madeira, and in the summer the ship cruised the Norwegian fjords. Passengers enjoyed structured activities like music, swimming, dancing, sports, and other games, and dining and entertainment.

The ship was billed as a low-cost alternative to a typical European cruise (passengers paid maybe 25 to 30 percent of what they would have paid for a cruise that wasn't hosted by the Nazi party), but the flipside was that they had to listen to a lot of Nazi propaganda while enjoying their evening entertainment. And their breakfast entertainment, and their everything else entertainment. Because above all, a cruise aboard the Gustloff was a way for the Nazis to communicate how awesome it was to be a Nazi, which is probably one of the reasons why most people outside of Germany didn't know much about the ship even in those days.

So who exactly was Wilhelm Gustloff?

Naturally, the Nazis decided to name their propaganda-mobile after a Nazi hero — a Swiss general who had recently been assassinated by a Jewish medical student. The Wilhelm Gustloff's namesake was a real stand-up guy who in the early 1930s decided that the one thing Switzerland really, really needed was some institutionalized anti-Semitism. As the founder of Switzerland's Nazi party, Gustloff attracted the attention of David Frankfurter, who fled Germany in 1933 after Hitler came into power and was at the time living in Bern, Switzerland.

According to Harretz, after Frankfurter learned that the Nazis were messing up the neighborhood (Gustloff was the dude responsible for the publication of the anti-Semitic text "Protocols of the Elders of Zion," if you're wondering just how despicable this guy actually was), he bought a gun, traveled to Gustloff's town, knocked on his front door and then politely waited in the study for Gustloff to finish some important business before shooting him five times and then turning himself in.

Frankfurter was convicted and sentenced to 18 years in prison, after which he was supposed to be kicked out of Switzerland. But then the war ended and everyone went, "Hmm, maybe you did us a favor," and he was granted clemency. Frankfurter ended up living happily ever after, and Gustloff, well, they named a ship after him.

Let's not maintain the Wilhelm Gustloff because it's not like we'll ever lose the war or anything

The Wilhelm Gustloff's career as a luxury liner was short-lived. Once the war got into full swing, the Nazis decided it might be better to convert the ship into something useful rather than having it ferry vacationing Nazis all over Europe where they might become the targets of people who were not such great fans of Nazi Germany. So after a brief stint as a hospital ship, the Gustloff was tied up in a Polish port, where it served as the home base for roughly 1,000 U-boat cadets.

The Gustloff played this role for four years, which meant it never got taken out to sea and was therefore not really maintained in seaworthy condition. According to the Wilhelm Gustloff museum, the ship's engines weren't really turned on much during those four years, except for infrequent "test runs." Meanwhile, the Gustloff kept losing the occasional lifeboat for some operation or another, so it was starting to look rather Titanic-y. But hey, it's not like the Nazis could have anticipated their great future takedown, so it must have not really occurred to them that they should, you know, cover all their bases. Anyway, the Gustloff wasn't exactly ready to go when the Germans decided it should be reinvented as a rescue ship. You can probably guess where this is going.

The Wilhelm Gustloff's final passengers weren't embarking on a luxury cruise

By the early weeks of 1945, it was starting to dawn on the Germans that maybe invading other European countries hadn't really been such an awesome idea. During the winter of 1944 and 1945, the Germans citizens who were once living happily in East Prussia realized that the Soviets were coming to get them, and the only any way out was across the sea. According to the National World War II Museum, families fled their homes and traveled on foot to the ports of Pillau and Gotenhafen, where they hoped to board ships en route for Germany. By the time they reached the coast there were thousands of refugees — 100,000 in Pillau alone — and the Nazi leadership didn't really know what to do with them. The German command argued about when to start the evacuation and who would be prioritized on the ship, and in the meantime the thousands of people waiting to get on board just became more and more desperate.

Passengers were supposed to have tickets, but the people in charge of boarding were getting mobbed by refugees and threatened by high-ranking Germans who were demanding a place onboard. By the time the ship departed, it was carrying around 10,000 people — nearly half of which were babies, children, and teenagers, even though it was only built to accommodate about 20 percent of that number.

If the Wilhelm Gustloff can just stay afloat, everything should be fine ...

When the Wilhelm Gustloff steamed out of Gotenhafen, it was a lot heavier than it should have been. But it limped through the water okay and headed west. The sea wasn't really much safer than land, though — according to Smithsonian, the shallow waters were full of mines, and the deeper waters were full of Soviet submarines. What's more, the Gustloff's convoy consisted of exactly one torpedo boat, which was sure to deter exactly no one.

It was even worse than that, though. It was late January and the weather was exactly like you might imagine it would be in the Baltic Sea in late January. There was snow and icy wind, which made for poor visibility and general misery for pretty much everyone from the passengers to the crew. After sunset the Gustloff switched on its navigation lights, which was basically like a giant shiny arrow bearing the words "aim here."

The Gustloff's progression was slow, too — the captain kept a snails-pace of 12 knots, mostly because he was worried that the ship's engines had sat for so long that they wouldn't be able to handle actual speed. Which would have been fine during peacetime, but the prevailing wisdom held that a ship needed to go at least 15 knots if it was going to outrun a submarine. So if the words "sitting duck" have just popped into your head, well, you're not wrong.

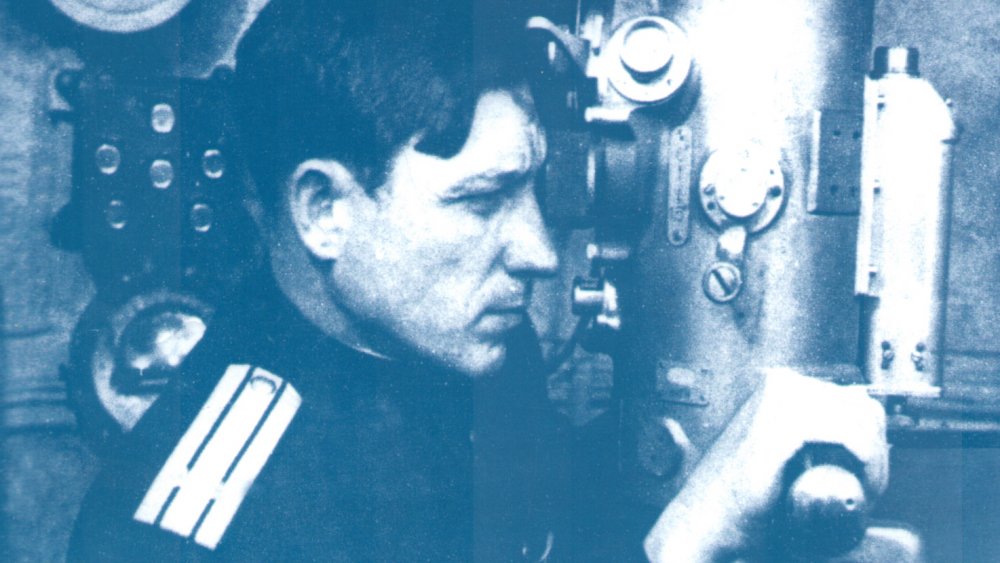

The submarine captain was probably drunk and wanted to be a hero by torpedoing the Wilhelm Gustloff

Soviet submarine commander Alexander Marinesko had a weird definition of "hero," but it's obvious he wanted to be one. According to Smithsonian, on the night of the sinking, Marinesko was under scrutiny by his higher-ups, not because he wasn't downing enough ships but because he'd been out partying the night before and had shown up late for his mission. So he hoped becoming a hero would bolster his reputation, and basically that meant sinking anything that didn't belong to the Soviets, regardless of how many children were on board.

To be fair, Marinesko had no way of knowing that nearly half of the Wilhelm Gustloff's passengers were kids, though no one can say for sure if that would have had any impact on what he chose to do next. When he saw the Gustloff steaming along with its lights on, he snuck up alongside it and fired three torpedoes. The first torpedo struck the Gustloff on the port side, destroying a bunch of crew cabins and the people who were inside of them. The second torpedo hit near the ship's pool, where 373 members of the German Women's Naval Auxillary were staying. Most of the victims in that part of the ship were killed by flying shrapnel after the decorative mosaics exploded and a glass ceiling came crashing down. The third torpedo — because clearly the first two weren't enough — struck the engine room.

There weren't enough lifeboats on the Wilhelm Gustloff

The first rule of avoiding maritime disasters is "make sure there are enough lifeboats." But the German command had either never heard of Titanic or just hadn't had time to think things through. By the time it occurred to anyone that maybe the Wilhelm Gustloff ought to have enough lifeboats for everyone on board, it was way too late. It's even worse than that, though. Not only did the Gustloff not have enough lifeboats, the weather and the ship's manner of sinking meant that many of the boats it did have weren't even accessible to the panicking passengers.

Titanic had the great luxury of taking a long time to sink, so in the early stages of the evacuation everyone was pretty calm and the loading of the lifeboats was an orderly procedure. Titanic also wasn't overloaded, so there were crowds but there wasn't a mob, at least not until much closer to the end. By contrast, the Gustloff was chaos, and because it was listing severely to the port side, all of the lifeboats on the starboard side were completely out of reach. And according to Time, some of the lifeboats that passengers were actually able to reach were frozen to the decks, which basically rendered them totally useless. Of those that did launch, some capsized and others tipped over before they even reached the water, dumping people into the frigid waters.

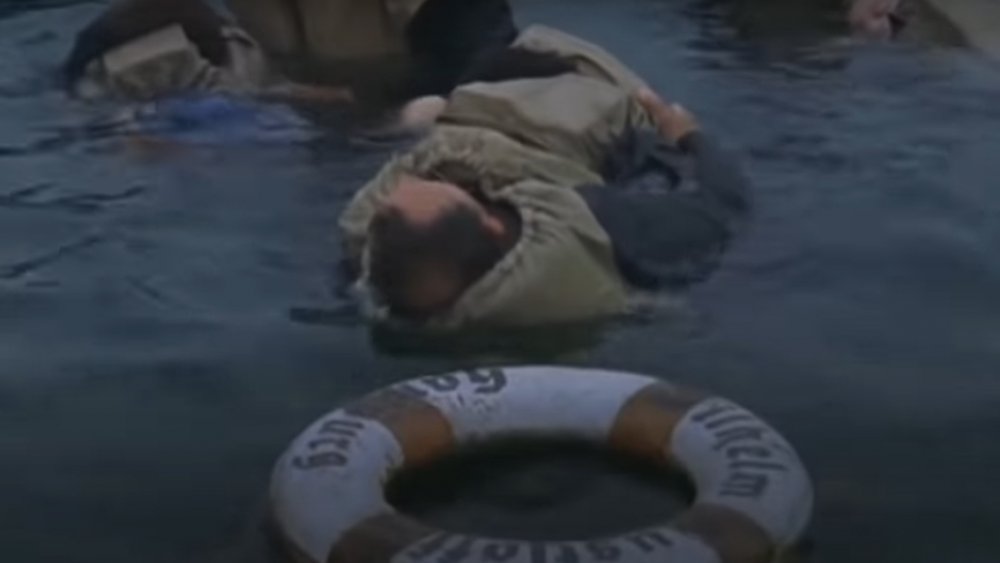

Those on the Wilhelm Gustloff who didn't drown froze to death

You almost certainly know that a lot of Titanic's passengers died because they froze to death. Because history just loves to repeat itself in very amplified ways, this was also one of the primary contributors to the deaths of the Wilhelm Gustloff's passengers, even those who were lucky enough to make it into a lifeboat. There were no icebergs on the Baltic sea that night — an iceberg is a huge chunk of ice that breaks off of a glacier and floats into the ocean — but there were ice floes, which are essentially chunks of frozen seawater. So in other words, it was so cold that the actual ocean was frozen.

According to the Warfare History Network, the outside temperatures, hail, and snow were probably responsible for ensuring that most of the Gustloff's passengers were sheltering below decks when the torpedoes struck, which means many of them died before they could make it up the steps. Anyone who jumped into the freezing water or was spilled out of a lifeboat died pretty quickly, too. The air temperature was roughly 14 degrees Fahrenheit, which is okay if you're really, really bundled up but will definitely kill you if you're still, say, wearing your pajamas after settling down for the night. So unless you were lucky enough to get picked up by a rescue ship, you weren't going to survive the sinking of the Gustloff.

Those on the Wilhelm Gustloff who didn't freeze or drown mostly ended up dying anyway

Drowning and freezing to death were the two major causes of death for Wilhelm Gustloff passengers, but people died in other horrible ways, too. A lot of them were killed in the initial torpedo blasts, which was probably the kindest way to go since many were asleep at the time and likely didn't even know what happened. For others, though, death was considerably more awful. According to Smithsonian, a large number of people died under the feet of stampeding passengers. Many were children, too, who were either separated from their parents or just caught in the deluge of humanity. Some of the people who jumped tried to get onboard lifeboats as they rowed away from the doomed ship, but most of those people were beaten back with oars for fear that they'd overload the lifeboats or capsize them while trying to get onboard. Other people were crushed to death by falling debris — some witnesses reported that the ship's grand piano killed people as it slid down the rapidly listing deck.

Murder/suicide was another way out for some of the people on board. One witness recalled watching a man shoot his wife and children to spare them from drowning or freezing to death in the icy cold water. Then, when he turned the gun on himself, he found he was out of bullets and had to resign himself to dying in the cold water anyway.

Rescue boats managed to save a handful of people on the Wilhelm Gustloff

The crazy thing about all of this is that there were actually some survivors. After word got out that the Wilhelm Gustloff had been struck, rescue boats sped to the scene even though they knew that submarines still lurked in the icy waters. According to the Wilhelm Gustloff Museum, the rescue boat T-36 captained by Robert Hering managed to scoop up 564 people while simultaneously dropping depth charges in the hope of destroying the submarine that had sent the Gustloff to the bottom of the sea. Other ships also saved handfuls of people. The torpedo boat that had acted as the Gustloff's convoy rescued 472 passengers, and three minesweepers recovered 98, 43, and 37 people. A steamer managed to save 28 people, a torpedo practice boat picked up seven, and a freighter took two survivors on board. That brings the grand total number of survivors to 1,251, or roughly 12 ½ percent of everyone who was on board. Some survivors were just left floating in lifeboats, because there weren't enough ships to rescue everyone.

Many lifeboat passengers froze to death before help arrived. One passenger described her rescue from a lifeboat containing 35 people, only five of whom were still living when the rescue boat arrived. And once on board a rescue ship it's not like they could relax, either. Rescue boats had to take evasive maneuvers to avoid the submarines that were still lurking in the area.

Only one person survived abandonment in the lifeboats from the Wilhelm Gustloff

By the next day, everyone who had been left behind was dead. Well, almost everyone. According to the Journal Courier, a patrol boat found one of the Wilhelm Gustloff's lifeboats at 5:30 a.m. the next morning. At first it appeared as if there was nothing left except a bunch of frozen corpses, but when Petty Officer Werner Fick climbed on board to make sure, he found a survivor — a baby wrapped tightly in blankets who had somehow managed to make it through the night.

There's a happy ending for the baby, who history remembers as the "Gustloff-Findling." Sort of. According to the University of Cincinnati, Fick adopted the boy, who grew up in Germany as Peter Fick. But not everyone was content to call it a happy ending. A man named Hermann Freymuller believed Peter Fick was actually his own son, who had been on the Gustloff with his mother and sister. Freymuller based his claim on a photograph he thought showed the resemblance between his son and the Gustloff-Findling, plus the sort of not very compelling evidence that the lifeboat where Fick found the boy had also contained the bodies of a woman and a young girl. Fick and his wife, understandably, chose to reject Freymuller's claim because they didn't feel like there was enough evidence, and because by that point they loved their son and didn't want to send him away to live with a stranger.