Tragic Details About The Founder Of America's First Lesbian Bar

Although Eve's Hangout only existed for two years, Eve Adams' legacy in Greenwich Village was not soon forgotten. Opened in 1925, Eve's Hangout can be considered the first lesbian bar in America, although since this was during Prohibition there was no alcohol being served. Eve's Hangout was considered a tearoom and a club, and in addition to serving tea in a queer-friendly environment, the space was also used for poetry readings, discussions, and musical performances. With a sign in the tearoom that read "Men are admitted but not welcome," the space was unapologetically for women, although many men, such as Henry Miller, frequented it as well.

Eve Adams was the life and soul of Eve's Hangout. Adams was friends with many of New York's activists and intelligentsia at the time and although Adams isn't as contemporarily known as her friend Emma Goldman, she and her tearoom were incredibly popular with the crowd of cultural activists.

Tragically, Adams' sexuality was used against her when a collection of short stories she'd written, Lesbian Love, resulting in an obscenity and disorderly conduct charge and her deportation in 1927. Unfortunately, after being deported by the United States back to Poland, Adams met an untimely demise at Auschwitz after the Nazis captured her in the south of France. These are some tragic details about the founder of America's first lesbian bar.

Emigration to the United States

Eve Adams, sometimes spelled Eve Addams, was born Chawa Czlotcheber (sometimes written Kotchever) in Mlawa, Poland in 1891. When she immigrated to the United States in 1912, she Anglicized her name to "Eve Adams." According to Gay New York by George Chauncey, this new name was an "androgynous pseudonym whose biblical origins her Protestant persecutors might well have found blasphemous."

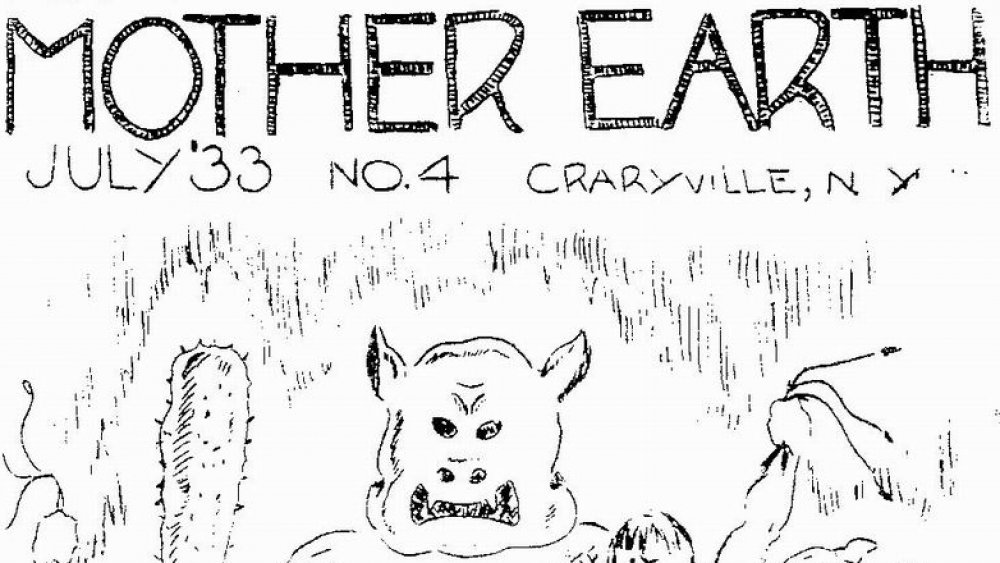

After moving to the United States, Adams and Ruth Norlander, her partner, traveled around the country selling The Masses, Mother Earth, and other radical papers. For a period of time in the 1920s, Adams and Norlander settled in Chicago and ran a gay-friendly anarchist café named The Gray Cottage in Chicago's Greenwich Village at 10 E. Chestnut St. where they offered both food and lectures.

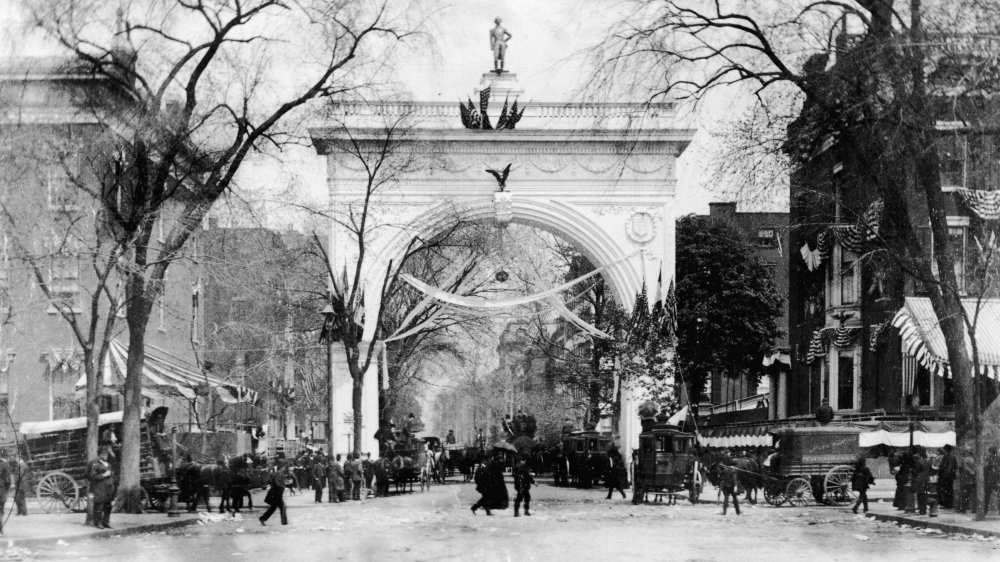

By 1925, Adams and Norlander had made their way to New York City. They settled in Greenwich Village, whose bohemian reputation was comparatively more accepting of their homosexuality than other parts of the city were at the time. But Greenwich Village wasn't the only place with queer nightlife. There were "world-renowned drag performances" in both Times Square and Harlem as well. Harlem's Hamilton Lodge had even been putting on drag balls since 1869.

Eve's Hangout

In 1925, Adams opened Eve's Hangout, also known as Eve Adams' Tearoom, at 129 MacDougal Street. It soon became one of the most popular spots of the neighborhood. According to NYC LGBT Sites, by the 1920s, Greenwich Village had become one of the first neighborhoods to accept an open lesbian and gay presence. Eve's Hangout was also especially appreciated after several police crackdowns in 1924 and 1925 had closed down several queer-friendly spots in the Village.

The tearoom became a welcome gathering spot and open parlor for immigrant intellectuals, women, and Jewish people. According to Atlas Obscura, the space was also created to be a space for queer women and frequently "hosted after-hours, locked-doors meetings, where women-loving women could share their experiences without fear of censorship or discrimination." At the time, women also rarely went into restaurants without a male guardian, but Eve's Hangout provided a safe space for women to venture into on their own.

Those who entered the tearoom were greeted by a sign that read "Men are admitted but not welcome," demonstrative of the spirit of the tearoom. This was taken in good humor by the men who frequented the tearoom, like Henry Miller. Adams even loaned money to Miller when his mistress couldn't afford to front his bills. In 1931, one columnist described the tearoom as "one of the most delightful hang-outs the Village ever had." Adams was even affectionately called "the queen of the third sex" by commentators.

Showcasing the works of local artists

Eve's Hangout provided not only refreshments and a communal space, but also frequently showcased the works of local poets, writers, and musicians. There were also discussion groups, often revolving around sexual topics.

According to Atlas Obscura, although the tearoom is often referred to as a speakeasy, the lack of police reports about alcohol suggests that the tearoom abided by the standards of Prohibition. Interestingly, the repeal of Prohibition laws in the 30s ended up being used against queer people when laws were changed to allow alcohol in places that were "orderly," which deliberately didn't include queer venues.

But in the two years that Eve's Hangout existed, it became one of the most popular establishments in the Village, where people could attend poetry readings and performances without fear of xenophobia or sexism. The tearoom was frequented by many artists and writers of the time, including Anaïs Nin and Emma Goldman, and Adams herself was popular among these radical cultural figures. Adams was a personal friend of Emma Goldman and had spread her writings during her time distributing Mother Earth.

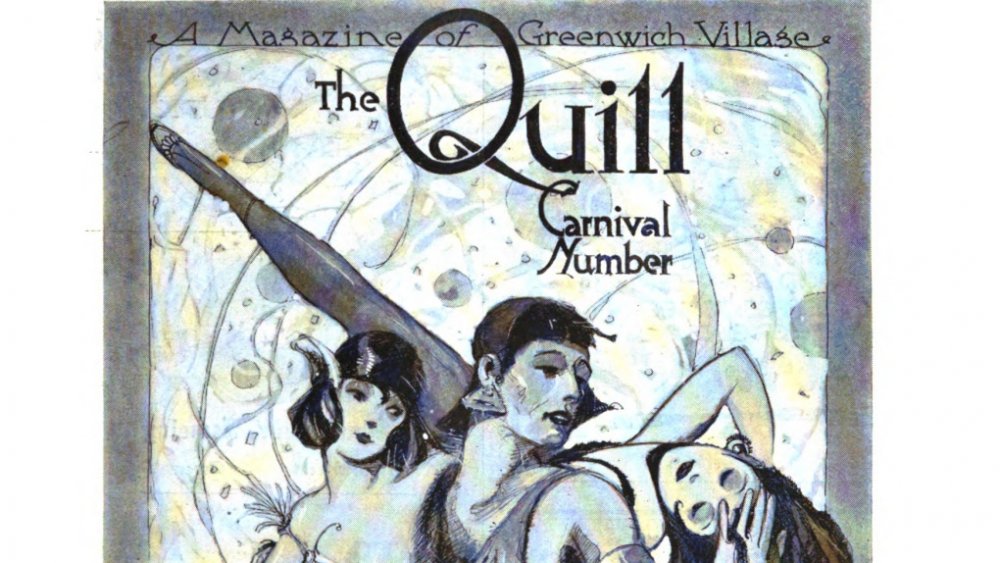

The vitriol of Bobby Edwards

Unfortunately, Adam's thriving tearoom drew the resentment of Bobby Edwards, a writer for the Greenwich Village Quill. With an office across the street from the tearoom, Edwards was especially displeased at the increased presence of lesbians and immigrants in the neighborhood. According to Gay New York by George Chauncey, Edwards refused to mention the tearoom in his column until June, 1926, and when he finally did mention it, his disgust was palpable. He described the tearoom as a place "where ladies prefer each other. Not very healthy for she-adolescents, nor comfortable for he-men."

It's more than likely that Edwards was involved in the police raid that ultimately led to the shutdown of the tearoom, for two nights after Edwards participated in a poetry reading at Eve's Hangout, it was raided by the police. At least one person posited the idea that Edwards was responsible for orchestrating a campaign against the visibility of lesbians that led directly to the police raid. Edwards seemed insulted by these charges and contested that although he'd "longed to cast out [from the Village] all radicals, Freudians, androgynes, narcissi, etc., ... I was no Mussolini."

But when Eve's Hangout was closed, Edwards made just a single mention of it in the September 1926 issue of the Village Quill with the line "Eve's place is gone," and noted that it had been replaced with a more "commendable proprietor." He also added charmingly that "boys must be boys. But girls mustn't."

The infiltration of Eve's Hangout

In the summer of 1926, Eve's Hangout was the target of a police raid that resulted in its unfortunate closure. Although police raids were common at this time, according to Atlas Obscura, the raid on Adams' tearoom was thought to be personal.

On June 11th, 1926, Margaret Leonard went to Eve's Hangout as an undercover policewoman. Although there are several stories as to what happened, Leonard alleged that Adams had made advanced on her and showed her a copy of Lesbian Love, a book of short stories that Adams had written and printed. While some accounts say that Adams spotted Leonard as an undercover officer, other sources say that Adams showed Leonard the book unbeknownst that Leonard was a police officer. Unfortunately, regardless of how it occurred, Leonard got her hands on a copy of Lesbian Love and Adams' fate was sealed.

According to the July 1926 issue of Variety Magazine, Leonard later claimed that "she was ordered to investigate the place as a result of complaints received concerning the actions of young girls." But ultimately, most of the charges were as a result of Adams' short stories. Leonard ended up sneaking out with a copy of Lesbian Love and later that night Adams was arrested at Eve's Hangout and charged with obscenity as well as disorderly conduct, based on "the general attitude and actions of Miss Addams[sic]."

The 'flapper squad'

Women began to join the ranks of police officers at the turn of the 20th century. According to the Los Angeles Almanac, Alice Stebins Wells was the first woman to be appointed as a police officer by the Los Angeles Police Department in 1910. In 1915, Well also founded the International Association of Women Police. By 1916, Wells' efforts in promoting the need for police officers who were women led to women being hired as police officers in 16 other cities in the United States. In 1916, the LAPD also recruited Georgia Ann Robinson to work for them, possibly making her the first Black woman law enforcement official in the United States.

According to Boston.com, the first group of women who became police officers in Boston were referred to as the "flapper squad" by the media. Their main responsibility was to watch over young women and keep them from "drinking with sailors and haunting nightclubs."

But many still struggled to be taken seriously. Officer Irene Bohmbach wasn't promoted over her husband because it "might cause discord in the home" although her husband was eventually promoted. And when Officer Sabina Delaney quit in 1922, she reportedly claimed that "no self-respecting woman could do the work assigned to her."

Eve Adams' arrest and conviction

Soon after Adams' encounter with Leonard, she was arrested and charged with disorderly conduct and obscenity. According to the July 1926 issue of Variety Magazine, Adams was found guilty for the possession and distribution of a "dirty" and "indecent book" in addition to her convictions for disorderly conduct. The magazine even described her as "a self-confessed 'man-hater'" who wore "mannish clothes." According to Atlas Obscura, one of Adams' neighbors, Jay Fitzpatrick, even alleged that she knew "personally of decent girls who have been corrupted by [Adams]."

Adams' uncle in Hartford had tried to pay her $1,000 bail, but it was refused by the City of New York, who preferred to rid Adams from their city.

Adams was sentenced to one year of labor at the Women's Workhouse on Welfare Island, now known as Roosevelt Island, and immigration authorities also used the charge as an excuse to deport Adams back to Poland "at the expiration of her sentence on the ground that she is not a citizen." By the following December, 1927, Adams was deported back to Poland by the United States government.

A chance encounter

While Adams was imprisoned at the Women's Workhouse on Welfare Island, she ran into someone else imprisoned on similar charges, American actress Mae West. According to Atlas Obscura, West had also been charged with distribution of obscenities as a result of her Broadway play, Sex. West was similarly accused of "corrupting the morals of youth."

However, West's imprisonment was drastically different from Adams'. West was incredibly popular as an actress, alternating between Broadway and vaudeville shows, and was considered a sex symbol at the time. Her fame provided her not only special treatment, but a quick release as well. During her imprisonment, West's celebrity allowed her various privileges including dinners with the warden. And West was only sentenced to 10 days compared to Adams' year imprisonment. West was also released early after only seven days while Adams was promptly deported back to Poland.

According to The Women Who Made New York by Julie Scelfo, Adams pleaded with the American authorities to allow her to stay, saying at her hearing that "I love this country with my whole heart and soul. I want to become a citizen. If I am deported, my life is ruined." While West's celebrity worked in her favor and she left prison as a national icon, Adams' status as an immigrant, Jewish lesbian earned her no compassion from the United States government. And tragically, her prediction about her post-deportation fate ended up coming true sooner than Adams may have feared.

Deportation to Europe

By the end of 1927, the United States deported Adams back to Poland. According to Atlas Obscura, there are many stories about what Adams got up to after her deportation and it's difficult to know for certain what she did and where she went.

Some claim that Adams went to Spain to fight against General Francisco Franco in the Spanish Civil War. However, there isn't any evidence that Adams did truly go to Spain. It appears as though this rumor was started by her family in an attempt to claim that Adams had left the United States voluntarily in order to fight against fascism.

What's known for sure is that by the early 1930s, Adams moved from Poland to Paris. Once there, she picked up where she'd left off in the United States, opened up another gay-friendly tearoom/bookstore in Montmartre and specialized in books targeted by censorship. She once more joined a circle of bohemian artists and was able to make a living selling English literature to expats and tourists. In the letters between Henry Miller and Adams, she even mentions selling copies of his book Tropic of Cancer.

Murder at Auschwitz

While Adams was initially able to have a comparatively peaceful life in Paris, homophobia and antisemitism found her in France when the Nazis marched into Paris in 1940. According to The Women Who Made New York by Julie Scelfo, as a result of the Nazi invasion, Adams fled south to Nice. She tried repeatedly to get help from foreign governments and friends, but with her American citizenship application discontinued and her Polish passport expired, Adams had little success. By this point, many of Adams' family members who'd remained in Poland had already been displaced or slaughtered by the Nazis.

In 1943, Nazi officer Alois Brunner took control of Nice and its surrounding territory. Along with hundreds of other Jewish people, Adams and her partner were collected and taken to a transit camp in France before being transported to Auschwitz. It was there that Adams was murdered in 1943, two years before the camp would finally be liberated.

Adams was not the only Jewish person who died at Auschwitz as a result of being denied entry into the United States. According to Facing History, in 1939, the United States State Department turned away a German ocean liner filled with Jewish refugees and sent them back to Europe, many of whom ended up being murdered in the Holocaust.

What happened to the tea room?

Adams' presence in the Village wasn't soon forgotten. According to Gay New York by George Chauncey, after her deportation, a play titled Modernity, based on Adams' Lesbian Love stories, ran for two weeks at the Play Mart cellar theatre. The play was mainly attended by queer people, and although it had intended to have a four-week run, the performers closed the play abruptly after learning that the police had planned a raid on it.

Eve's Hangout was closed after Adams' arrest and, according to Bobby Edwards, was replaced by a more "commendable proprietor." But even five years after Eve's Hangout had closed, many Villagers lamented its destruction and remembered the raid bitterly. According to Daytonian in Manhattan, during the mid-1930s, the various studios in 129 MacDougal were joined together to create a roof "studio dormer." By 1950, the parlor floor was also turned into a commercial storefront and a decorator store opened in 1951. Funnily enough, when the New York Times wrote an article on the shop two years later, on December 11th, 1953, their headline read "Gay Fabric Items Shown in Two Shops."

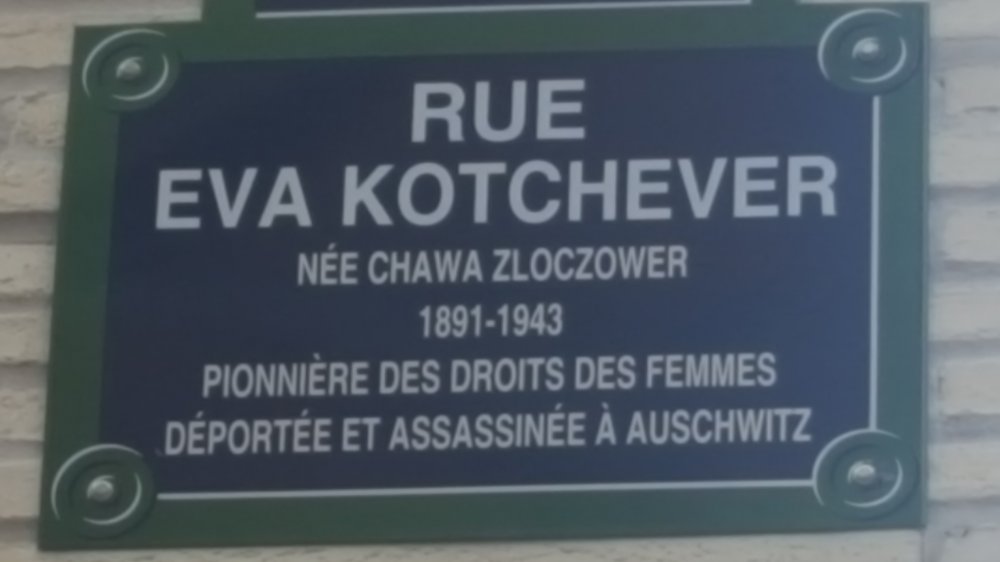

Today, the former site of Eve's Hangout houses an Italian café near the NYU campus. A street in Paris has also been named after Adams in honor of her memory.