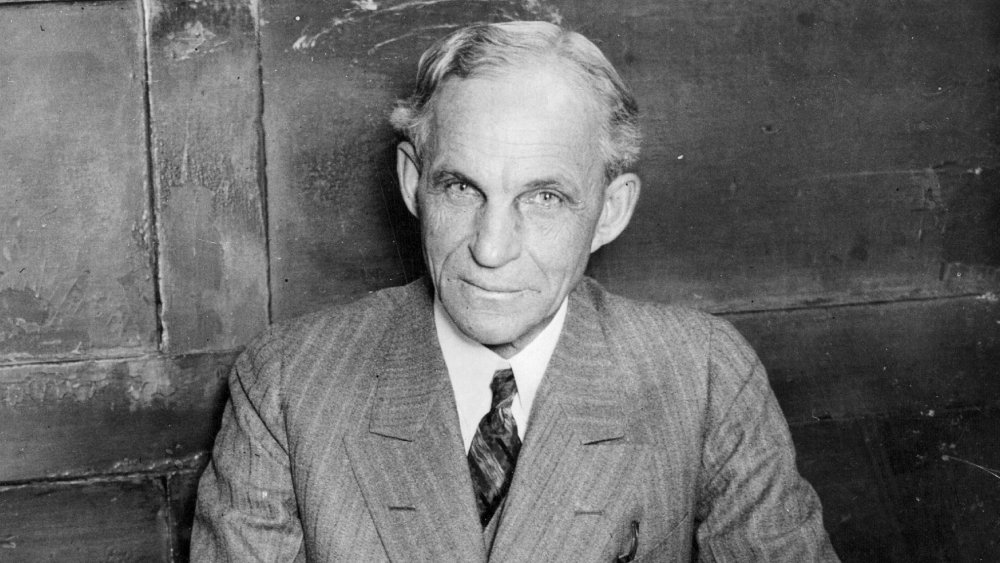

The Truth About Henry Ford's Dark Side

More than anyone else, Henry Ford is responsible for making cars a ubiquitous part of American life. As noted by Construction magazine, Ford didn't invent the car, the car's interchangeable parts, or the assembly line, but as an entrepreneur, Ford "changed the world by catapulting his United States into the lead of an industrial race that dated back decades." Ford's Model T car was both affordable and profitable. Cars were no longer just for rich people; they were for "the millions of workers that kept the upper class afloat." Ford also prioritized paying his workers a living wage, doubling the then-minimum wage to $5 per day and giving rise to "a clear middle class."

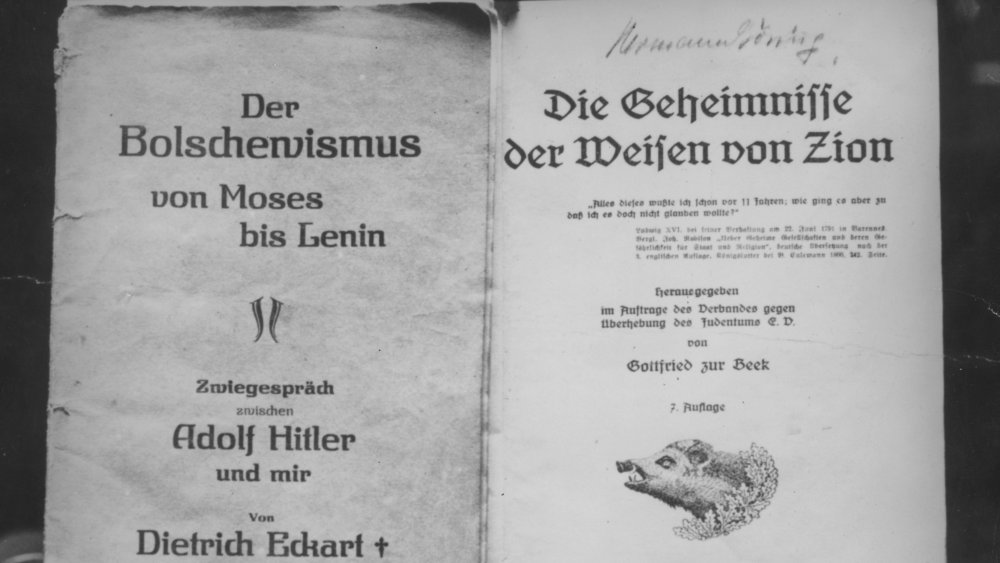

Unfortunately, Henry Ford also had some extremely disturbing beliefs, centered around his raging anti-Semitism. During the 1920s, Ford was in his late 50s. As some older people tend to do, he crankily complained about several aspects of what was then modern life, including World War I, short skirts, and jazz, according to The Henry Ford's website. Ford took this dissatisfaction in a hateful direction, blaming "the Jews" and "the bankers" for what he saw as problems with society. Ford owned a newspaper, the Dearborn Independent, and from 1920 to 1922 the paper ran a weekly series on its front page, titled "The International Jew: The World's Problem." Inspired by the anti-Semitic hoax Protocols of the Elders of Zion, the column examined bogus conspiracy theories surrounding Jewish peoples' quest for world domination.

'Henry Ford legitimized ideas that otherwise may have been given little authority'

Ford later bound the articles into four volumes and distributed half a million copies. He also reprinted Protocols of the Elders of Zion within his paper and treated it as fact. PBS pointed out that by using his publishing platform, "Henry Ford legitimized ideas that otherwise may have been given little authority." While anti-immigrant and nativist groups saw their own beliefs reflected back to them in the anti-Semitic column, many people were horrified and demanded retractions, refused to carry the Dearborn Independent, and boycotted Ford automobiles. Henry Ford responded by stopping the column in January 1922, but it was back in less than a year, per The Henry Ford website.

Things reached a boiling point when the paper printed a series of articles accusing Jewish lawyer and activist Aaron Sapiro of "exploiting farmers' collectives." Sapiro sued for libel, and brought Ford to trial. Ford closed down the Dearborn Independent just before he was scheduled to testify. He agreed to issue a formal apology and provided Sapiro with a cash settlement.

'I regard Henry Ford as my inspiration'

Ford's anti-Semitism was so well-known and expansive that Adolf Hitler was a fan. According to Deadline Detroit, in a 1931 interview with a Detroit News reporter that took place in Hitler's office, Hitler indicated the portrait of Ford hanging on the wall and said, "I regard Henry Ford as my inspiration." Hitler's book Mein Kampf also lauded Ford, gushing over his supposed freedom from Jewish influence: "Only a single great man, Ford, to their fury, still maintains full independence." Per The Nation, Germany went on to award Ford the Grand Cross of the German Eagle, "the Nazi regime's highest honor for foreigners," and Ford accepted, despite the fact that "the vicious character of Hitler's government had become clear."

Ford Motor had a presence in Germany starting in 1925 and "prospered" during the Nazi regime; Ford of Germany's value doubled during World War II and the company was producing military vehicles for the Reich "even before the war began."

People were reminded of Ford's notorious anti-Semitism in May of 2020 when President Donald Trump, while touring a Ford plant in Ypsilanti, Michigan, reportedly commented, "The company founded by a man named Henry Ford — good bloodlines, good bloodlines if you believe in that stuff. You got good blood," as reported in USA Today. The White House did not respond to what Former White House ethics chief Walter Shaub called "gaslit dog whistling" regarding the term "bloodlines," often used when discussing eugenics.