Messed Up Reasons These Books Were Banned

The burning and banning of books have been associated with some of the darkest moments in human history. In 1933, the Nazi party of Germany began burning books that they believed undermined their ideology, among them works by Karl Marx, Sigmund Freud, and Helen Keller, as well as socialist and anti-war works by Jack London and Ernest Hemingway.

But the fact is that the suppression of literature is no rare event, and attempts to get books banned or, at any rate, taken from the shelves of public schools and libraries, recurs around the world today. Most of the time, people's objections to works of literature come from a genuine belief in the book's unsuitability — that certain books are too "adult" for children, or that coarse language or graphic scenes might cause offense to readers. The American Library Association keeps track of how often books are "challenged" by members of the public, to draw attention to the ongoing, potentially dangerous phenomenon of censorship. It seems, with the frequency of attempted bans, it could be argued that we are barely less puritan in our taste in literature than we were when the ALA first began monitoring censorship back in the 1980s.

The Irish wit Oscar Wilde, whose own writings were often subject to censorship, wrote in his novel The Picture of Dorian Gray: "The books that the world calls immoral are books that show the world its own shame." That was written in 1890, but perhaps it is a point that we still have yet to learn. Here are some of the most misguided attempts to suppress books that have occurred over the years.

Negativism got The Wizard of Oz banned in Detroit

It is unthinkable that someone might object to L. Frank Baum's The Wonderful Wizard of Oz today. The story, its characters, and images — and especially the songs from the enduring 1939 movie — are too ingrained into our collective psyche to ever feel like something subversive.

But in 1957, the libraries of Detroit apparently found some reason to take issue with it — well, with a recently released printed version, at least. According to an archived column from the Chicago Tribune, the director of Detroit's library system – whom the Tribune books columnist describes as "talking thru his hat" – had reportedly pulled the tale of Dorothy and her ragtag troupe's journey down the yellow brick road on the grounds that it was of "no value" to children, brought their minds to a "cowardly level," and promoted "negativism." According to Open Culture, the ban was in effect until 1972.

What we as a society expect to receive from the act of reading has come on leaps and bounds since the 1950s, and it is worth reminding ourselves in the face of such remarks that the humanist tradition which called for art to represent "societal ideals" and to build the reader's "moral character" was the dominant mode in which literature was discussed well into the 20th century. However, the reason Baum's classic was singled out for exclusion when its moral messages are so obvious is still a mystery.

Ulysses was banned for the sake of women

There were many reasons for James Joyce's masterpiece, Ulysses, to cause a stir when it was first published in 1922. Ostensibly the tale of Leopold Bloom's travels around Dublin over the course of 24 hours, the novel also includes scenes of defecation and masturbation, as well as many passages that were deemed blasphemous. Politics and Prose claims that Ulysses was "burned in serialized form in the U.S. in 1918 before it was burned as a published manuscript in Ireland in 1922, Canada in 1922, and England in 1923." The novel was banned in the US two years before publication following its serialization in Ezra Pound's magazine The Little Review and was banned in England, per the British Library.

However, the literary critic Kevin Birmingham has highlighted the irony of the suppression of Ulysses, namely, that it the censors aimed "to protect the delicate sensibilities of female readers," while the truth is that Ulysses "owes its existence to several women," such as the publisher Sylvia Beach, Joyce's patron Harriet Weaver, and, most importantly, Joyce's partner, Nora Barnacle. It is Barnacle who is now widely believed to be the model for the character Molly Bloom, whose stream-of-consciousness monologue forms the finale of the book and is a groundbreaking representation of the female psyche and sexual desire. In many ways, Ulysses' censors were attempting to keep women from seeing themselves represented too candidly.

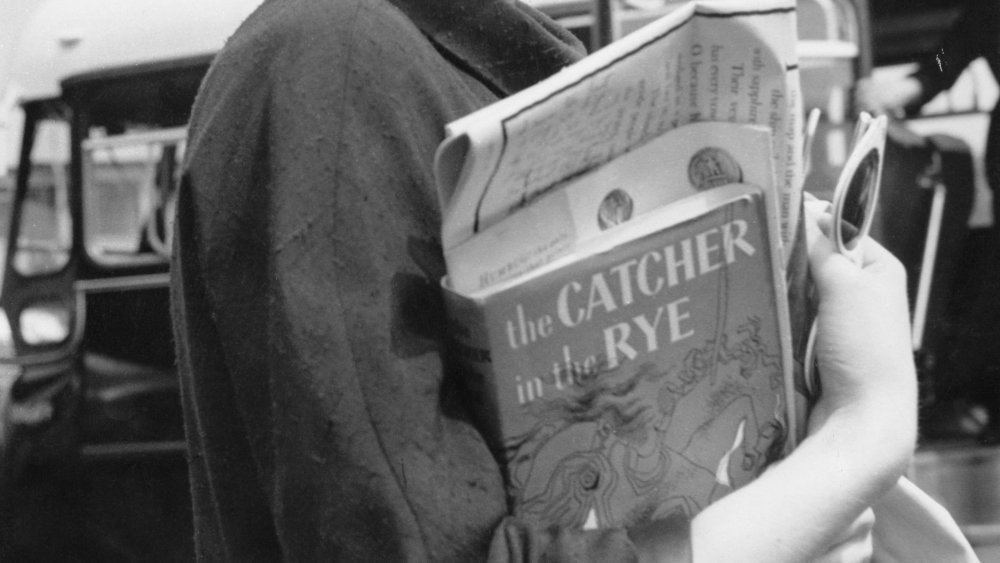

The Catcher in the Rye was suspected to be part of a communist conspiracy

The most famous work of the reclusive writer J. D. Salinger, The Catcher in the Rye has enjoyed an enduring audience – and ongoing controversy – since its publication more than 65 years ago. The Irish Times claims that as recently as 2011 the novel was still selling upwards of 250,000 copies a year worldwide.

Though the complex personality of the protagonist Holden Caulfield and the novel's themes of non-conformity, isolation, and adolescent angst are the most likely reasons for the book's timeless appeal, Catcher's notoriety also plays some part in those high sales figures. As the Guardian notes, the book has been closely associated with some high profile murder cases, including the 1980 shooting of John Lennon by Mark Chapman, a deranged Beatles fan who offered up Catcher to the police during his arrest as a way of explanation. Similarly, the murderer Robert John Bardo had a copy on him the night he killed Rebecca Schaeffer.

And while the American Library Association notes that Catcher has been a "favorite target of censors" over the years, one reason for its suppression sticks out among all others: namely, the incident in 1978 in Issaquah, Washington, when the book was removed from high schools in the belief that it was part of "an overall communist plot," according to the academic Raychel Haugrud Reiff.

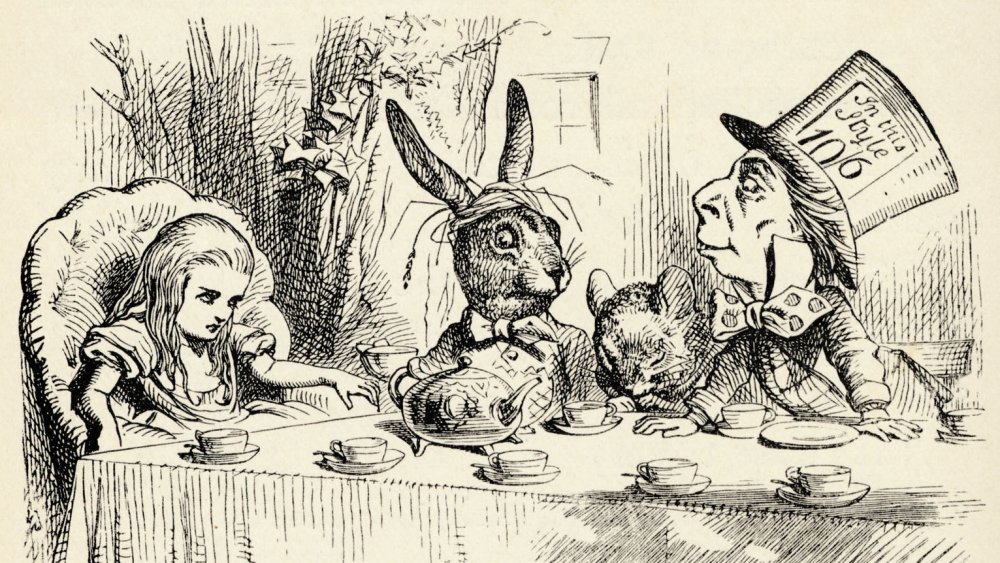

Alice in Wonderland has been banned for nonsensical reasons

Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland is a cornerstone of nonsense literature and a tour de force of illogical imagining. The White Rabbit, the Hatter, and Cheshire Cat have all entered the popular consciousness, while the absurdist language used is now legendary.

However, as Britannica mentions, Carroll's magnum opus was banned in one U.S. school in 1900 under the apprehension that the novel contains sexual subjects and allusions to — bafflingly — masturbation. However, critics have since pointed out that the ban was due to anxieties over the author's own personal life, rather than what could be found in the book itself.

In the 1930s, the book was then banned in a province of China after the governor took issue with the book's speaking animals, apparently "worried that the consequences of elevating animals to the same echelon as humans could be catastrophic for society," according to Britannica. In the 1960s, a decade after the animated Disney movie was released, the book again raised anxieties for American parents who saw parallels between the book's imagery and the psychedelic stylings of the decade's LSD-loving hippie movement ... although Carroll's book was a century-old by then.

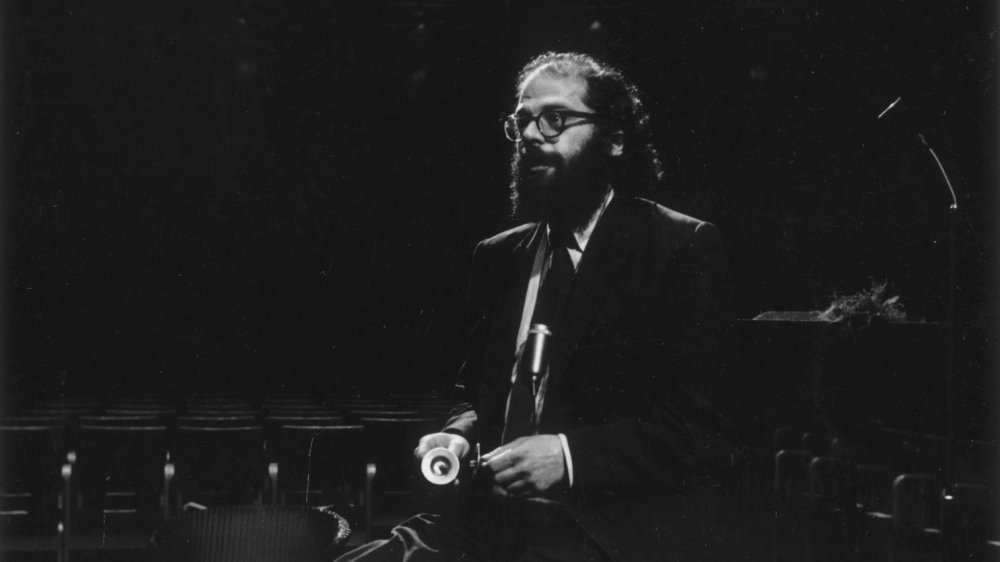

Allen Ginsberg's Howl was seized as obscene cargo

"Howl" caused a sensation when it was first performed by the Beat Generation vanguard Allen Ginsberg at the Six Gallery in San Francisco in 1955, and today the long poem is known as one of the great works of American literature. Michael McClure, who was in attendance along with many others who would go on to become notable literary figures in the late 1950s and early 1960s, later wrote: "Ginsberg read on to the end of the poem, which left us standing in wonder, or cheering and wondering, but knowing at the deepest level that a barrier had been broken, that a human voice and body had been hurled against the harsh wall of America."

By the time of its publication through Lawrence Fehlinghetti's City Lights Books, the poem was notorious for its raw and honest depictions of homosexuality and drug use, leading to 500 copies of the book being seized by the San Francisco Collector of Customs and the arrest of Fehlinghetti for publishing obscene material, according to the The Fire.

The result was a landmark obscenity trial, in which Judge Clayton Horn eventually ruled that "Howl" was an important work of art, stating: "No hard and fast rule can be fixed for the determination of what is obscene, because such determination depends on the locale, the time, the mind of the community and the prevailing mores. Even the word itself has had a chameleon-like history through the past."

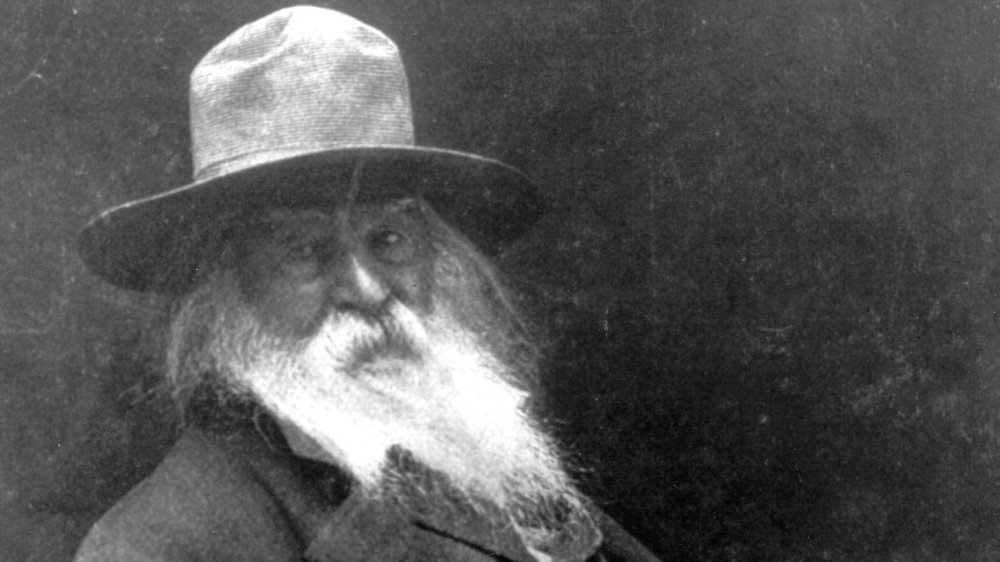

Walt Whitman, the father of free verse, was filthy

Not that suppressing landmark American poetry is anything new. All the way back in the nineteenth century, Walt Whitman — in many ways one of the forebears of the Beat Generation — was having his own epic and era-defining work challenged by the censors of his day.

Many critics and fellow poets took issue with Whitman's defining work, Leaves of Grass, first published in 1855, though revised numerous times throughout the poet's life. The collection is characterized by its overt sensual and sexual imagery which, though tame by today's standards, so scandalized one reader that they burned their copy, according to the critic James E. Miller, while one critic described it as a "mass of stupid filth" due to the perception that it promoted free love, per the Walt Whitman Archive.

According to the Whitman Archive, the New England Society for the Suppression of Vice — a real society, with branches all over America — lobbied in 1882 to have Leaves of Grass withdrawn from publication, claiming it defied, "the Public Statutes concerning obscene literature." Potential alterations that could make the volume suitable for publication were suggested to Whitman, who refused them. His book was then famously "banned in Boston," which, though unfortunate, reportedly helped to boost sales of the collection elsewhere.

A Clockwork Orange became infamous thanks to Kubrick

Stanley Kubrick's 1971 adaptation of Anthony Burgess' A Clockwork Orange, which was published in 1962, is rightly considered a classic of cinema and one of the most striking and memorable movies in the director's canon. However, while the movie has had a hand in establishing Burgess' novel as a cult classic, Kubrick's work also caused some headaches for the English writer after its release.

On the mildly-irritating end of the spectrum is the fact, due to the movie's fame and notoriety, A Clockwork Orange came to overshadow the rest of Burgess' writing, though he wrote and published continuously until his death in 1993. But more seriously, the withdrawal of Kubrick's movie from UK circulation in 1973 — which followed anxiety around supposed copycat attacks, according to PBS — meant that Burgess' novel has, despite its satirical intent and knotty, non-standard language ("Nadsat"), been continually challenged for its violent sexual content. According to The Banned Books Project, a bookseller in Orem, Utah, was arrested for selling the novel alongside other "obscene" literature, while as recently as 2019, the Florida Citizens Alliance lobbied against the work, claiming it to be "pornographic."

Lord of the Flies was too close to home

High on the American Library Association's list of frequently challenged books is Nobel Prize-winning author William Golding's 1954 tale of a group of British schoolboys are stranded on an eerie, uninhabited island, their attempts to form a rudimentary society of their own, and their subsequent descent into paranoia and animalistic violence.

ThoughtCo. explains some of the specific reasons why Lord of the Flies has been challenged by potential censors, most strikingly the racial slurs that recur throughout the novel. It is this aspect of the novel that has drawn opposition in 1988 from parents of schoolchildren in Toronto, Canada, who have stated that the book "denigrated Black people."

More widely, however, there have been a number of challenges that seem to oppose the very message of the book itself. The ALA notes that, in 1981, Lord of the Flies was challenged at schools in North Carolina due to the novel being "demoralizing inasmuch as it implies that man is little more than an animal." In this case, it would appear that those opposing the book just don't want to hear what it has to say.

Waldo's longrunning nudity scandal

For many of us, the 1990s is the decade we revisit for a dose of sweet nostalgia, the decade of Friends, mixtapes, and good, innocent fun. However, everyone's favorite decade had its own share of literary scandals that reveal that the '90s had its own silly puritan streak. The book in question? Martin Handford's childhood classic Where's Waldo?

For anyone who doesn't know the Waldo books, the concept is simple: the reader has to find Waldo on each page, which is densely populated with thousands of minuscule characters in a range of locations. And unbelievably, it is one of these characters that is the reason Waldo was one of the most challenged library books of the 90s in the US.

According to the East Lansing Public Library, the book garnered a number of complains when shocked parents realized that, on one page depicting scores of scantily clad sunbathers on a packed beach, one of Handford's figures is depicted topless — with a hint of nipple to boot. Quite how this microscopic detail might be damaging to children is unclear, but apparently, Waldo's publishers eventually yielded to the pressure of the no-nipple lobby, and in later editions of the book the figure has been edited, and now wears a lime green bikini top.

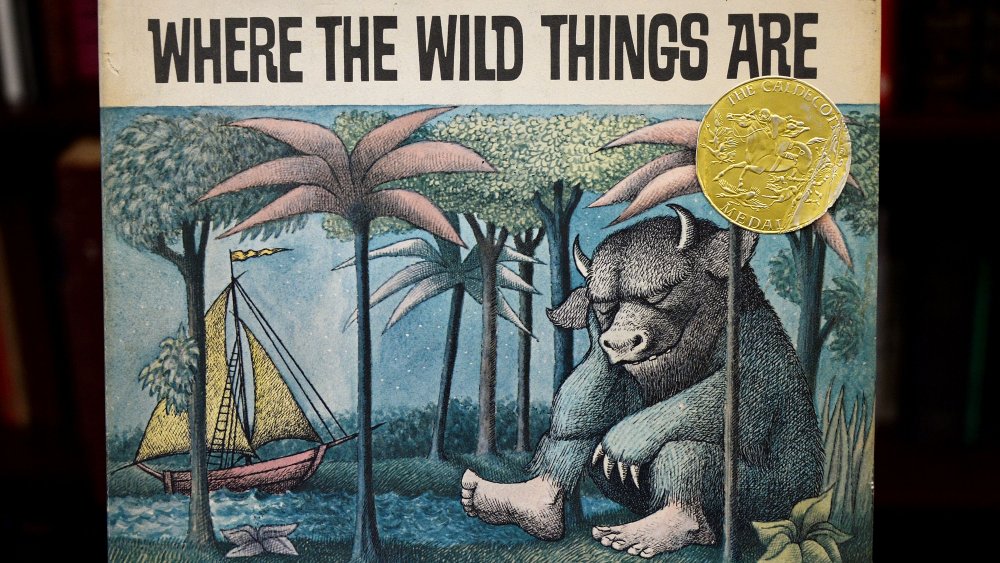

Where The Wild Things Are suppressed

It is surprisingly common for mainstream children's literature to attract vocal opposition from worried parents who find the content of this highly popular genre too immoral, too non-religious, or too adult for their children to cope with. The Harry Potter series is one of the most challenged books in recent years due to being perceived by many as anti-Christian, while according to Reading Partners, Roald Dahl's James & the Giant Peach is often challenged as too scary for its target age group. Although, I'm sure most of us can remember having a fascination with the more macabre elements of the entertainment we engaged with as children.

Another children's book to make a surprising appearance on the "most challenged" list is Maurice Sendak's 1963 classic Where the Wild Things Are. According to PEN America, Sendak's publishers, Harper & Row, were originally hesitant to publish the story of a boy who goes to bed without any dinner and, in his hunger, is transported to a jungle-tangled island inhabited by giant beasts. But its themes of "rebellion, fear, punishment, and escape" are, as PEN states, "exactly why it was an immediate hit."

The story's darker elements have, however, also drawn the censors, especially in the south of the US, where it was removed from many schools and libraries, while some opponents claim that the sending of a child to bed with no dinner is basically abuse.

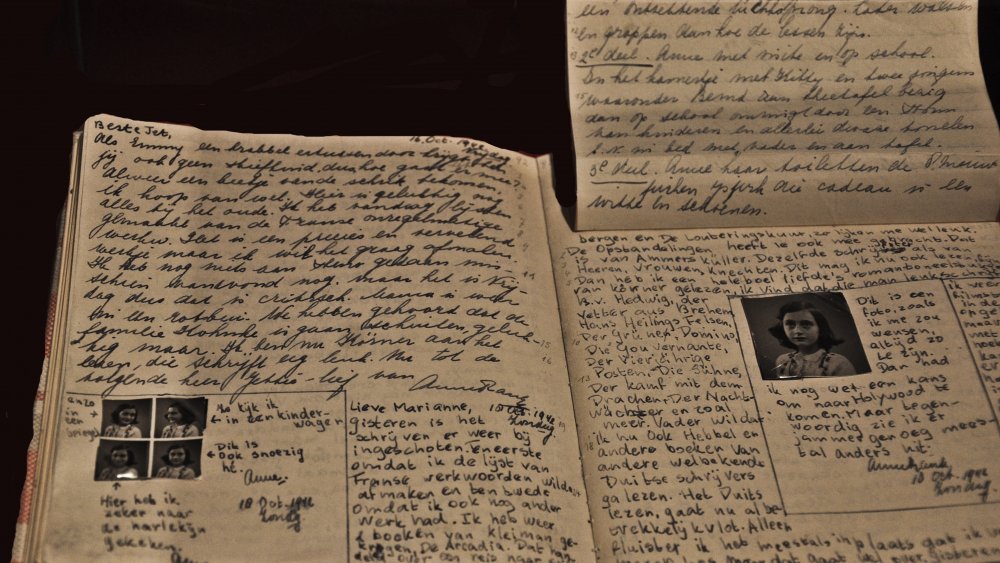

Anne Frank's diary: Too depressing

The heading of this paragraph is not an attempt to make light of The Diary of a Young Girl, more commonly known as The Diary of Anne Frank. The book was composed by a young Jewish girl over the course of two years, during which she and her family were in hiding from the Nazis during the occupation of the Netherlands in the early 1940s. The family was apprehended by the Nazis in 1944, and Anne Frank is known to have died of typhus in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in 1945. Anne's father Otto, the only member of the family known to have survived the Holocaust, had his daughter's writings published in Amsterdam in 1947, where they were met with widespread critical attention and scholarly appreciation of its vast importance as a historical text, which has never wavered. It is, simply, essential reading.

So it really is jaw-dropping that, in 1983, four members of the Alabama State Textbook Committee rejected the book for teaching in schools, according to The Atlantic, claiming that the book was "a real downer." It might be funny if it wasn't so completely and utterly offensive, but it does serve to highlight the thoughtlessness that motivates much of the censorship that the world has had to contend with through the years.