Comanche: The Most Powerful Native American Tribe In History

For many Americans, the story of how we conquered the continent is a straightforward one. It's a story of brutally inevitable conquest, of an advanced nation hungry for territory overpowering a weak coalition of indigenous people who are often portrayed as ignorant and even savage. Even when the violence and brutality of America's tactics are acknowledged, there is usually still the assumption that the Native American civilizations we conquered never stood a chance.

But pull on any thread in that narrative and it falls apart. The Native Americans who found themselves fighting for their lives against the United States were diverse, representing many thriving and complex civilizations—and they were more effective at fighting an endless war against impossible odds than you might think.

Case in point: The Comanches. This Native American nation was once the most powerful in America—and one of the most effective fighting forces in history, hands down. They once controlled a vast empire in the heartland of what would become parts of Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, New Mexico, and Texas, and they held off invaders for decades. They were only defeated in the late 19th century, and that defeat required more than American soldiers to bring about. Here's the secret story of the Comanche: The most powerful Native American tribe in history.

Horses changed everything

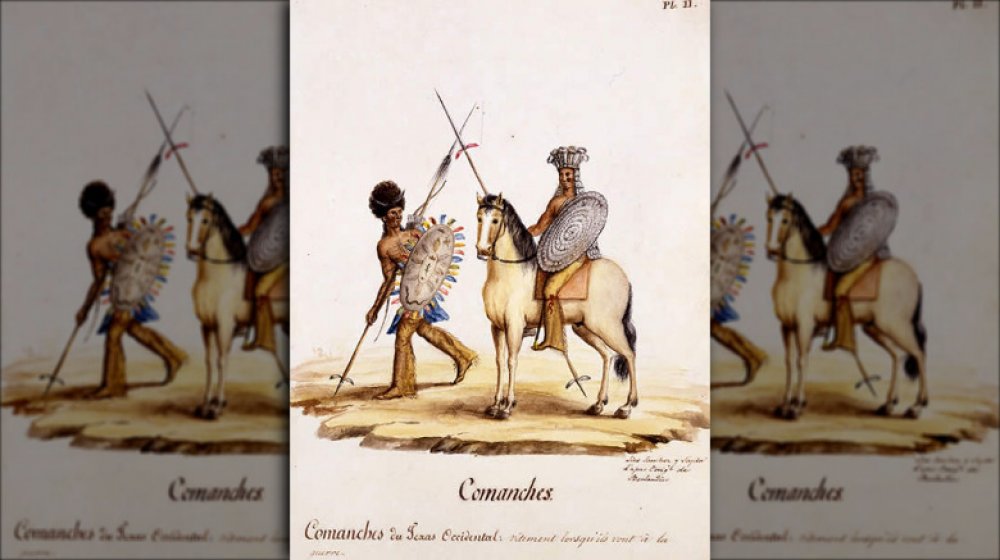

The popular image of the Native American in the 19th century invariably shows them as badass warriors who live their lives on horseback. And while the Comanche were unparalleled warriors on horseback, this wasn't always the case. As author S.C. Gwynne writes, the Comanche were originally nomadic hunter-gatherers who moved following seasonal prey. In many ways they lagged behind their peers—while the Aztec Empire was building incredible cities and the Iroquois were developing a sophisticated civilization, the Comanche built nothing and had no permanent settlements. They were also not particularly aggressive, which might have had to do with the fact that they also weren't notably good warriors.

But all this changed in the late 17th century, when the Comanche first encountered the horse.

The Spanish introduced the animals to the Comanche, but the Indians demonstrated an understanding of both how to master these incredible animals and how to translate that mastery into military force. Over the course of the next century, the weak hunter-gatherers of the Comanche Nation transformed into a dominant, aggressive empire of warriors, and it was all due to their expertise in breaking, training, riding, and fighting with the horse. The horse was a super-weapon in the 18th and 19th centuries, and the Comanche used it to conquer most of the neighboring tribes.

The Comanche were almost completely focused on war

For a tribe that had its beginnings as relatively peaceful hunter-gatherers, the Comanche's transformation into a military juggernaut was almost total. Once they acquired horses and a mastery over them that no other people could match, their culture became almost solely focused on waging war.

As NPR reports, Comanche society was very limited. They didn't have a religious structure, they didn't have social organizations. There was no manufacturing or even art. Children learned how to ride, how to hunt, and how to fight from a very early age, and their entire lives would be focused on those three aspects. Author S.C. Gwynne compares the Comanches to the Spartans in how they were almost totally focused on fighting.

As a result, the Comanches evolved into a force of violence that no one could withstand. They waged war on everyone who came into contact with them—and usually won. One reason for this success was their brutality. A Comanche raid was a terrifying affair. All male enemies would be killed, without exception—even if they surrendered. Older children would be killed as well. Young children would be taken captive, and the women would be sexually assaulted and killed. The Comanches waged Total War long before the United States.

They were a representative democracy

In popular culture, the generic image of an Indian tribe is one where a Chief presides like a monarch. Famous Indian Chiefs like Sitting Bull have made this the most common depiction of Native American government structure.

Despite having a few famous Chiefs of their own, the Comanches were not this organized or unified. As historian Thomas Kavanagh explains, the Comanche Nation was divided into "bands," which were centered on a patriarch and usually comprised of extended relatives. Sometimes these bands could be hundreds strong, and the elder patriarch was usually referred to as a chief. These bands would then combine informally into a tribe or nation, but this was based on mutual need or advantage.

Comanche government was therefore very council-based, with elders gathering on a formal and informal basis to discuss issues and come to decisions. While there were at times a single "great chief" acknowledged by the others, it was not a formal position and didn't change the fact that the Comanches governed themselves via a council where representatives had a vote, not any sort of monarchy. In fact, the different nations or bands within the Comanche political structure made their own policies and decisions based on their own needs, without any sort of central authority like a president or a king.

The Comanche nearly destroyed several other tribes

In order to appreciate just how powerful and warlike the Comanches were at their height, you have to consider the fact that they came very close to wiping out several other Indian tribes. The Native Americans who resisted the expansion of the United States into the Midwest weren't a single culture. They were a diverse group of separate nations that shared many cultural ties and traditions.

And as NPR explains, the Comanches were particularly aggressive against their fellow Native Americans—and particularly effective at killing them. They systematically pushed all the other tribes off the central plains, forcing them to find new lands to live on. In fact, as author S.C. Gwynne writes, the Comanches came very close to literally wiping out the entire Apache Nation, savagely defeating them in a series of conflicts that saw the desperate Apaches beg the Spanish for protection, and several large tribes within the Apache Nation simply disappeared as a result.

But it wasn't just the Apaches. The Comanches inflicted severe damage on the Pawnees, the Osages, the Blackfeet, the Kiowas, and the Tonkawas, driving them off their traditional lands and killing thousands of their people. By 1750, the Comanches had total control of the plains, and other Native American Nations respected their borders.

The Comanche were adaptable

The story of the Comanche Nation is one of brutal war and eventual defeat—but it's also a story of evolution and adaptability. In fact, author and historian Pekka Hämäläinen describes the Comanches as "an extraordinarily adaptive people." They were a people who quickly grasped the military applications of the horse and completely transformed their entire society around it within a few decades while other tribes like the Apache remained incapable of similar changes. They then altered their entire diet to be more or less entirely dependent on a single food source: The buffalo, thus increasing their caloric intake to unheard of levels that fueled their wars.

The adaptability didn't stop there. While their aggressively violent warfare gained them an empire, one reason they thrived was their collective willingness to absorb from the cultures they encountered, embracing innovations and consistently re-inventing their approach. Despite being a nation of horse warriors who had once been nomads, the Comanches quickly adopted the concept of the Winter Village from other tribes, using these large-scale and temporary settlements to not only safeguard their horses and herds, but to cement their control over a local area. It was this willingness to change that maintained the Comanches' power even when other tribes replicated their transformation into a nation on horseback.

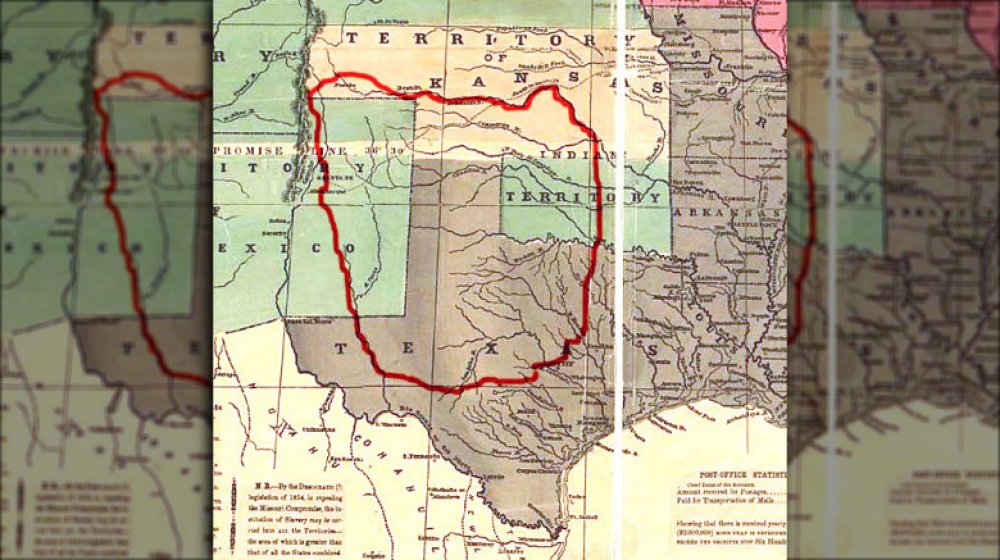

The Comancheria was huge

The territory controlled by the Comanche was called the Comancheria by the Spanish, and it grew with astonishing speed. After the horse transformed their entire society into a mobile war machine, the Comanches began their transformation into the Lords of the Plains—and came to control a huge swath of territory in the process.

As NPR reports, over the course of about 150 years the Comanches steadily drove rival tribes before them, conquering land and subjugating everyone they didn't kill. When Americans began venturing west and finally brushed up against the Comancheria in the 1820s, it was an empire. The Comanches controlled about 250,000 square miles, including parts of five eventual states (Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, New Mexico, and Texas). They also had vassals, with about 20 other tribes acknowledging Comanche supremacy.

According to historian Pekka Hämäläinen, this makes the Comancheria something more than just a Native American tribe or nation—an empire. They conquered lands and absorbed other ethnicities and cultures, imposed their own political and military structures, and negotiated as a single unit. In fact, the Comanche Empire was more powerful and more advanced than many of the European Empires of the time. This is why the colonization efforts of the Spanish, French, and Americans stalled whenever they pushed up against the Comancheria.

The Comanche stopped the Spanish—and the French

The British settlers who eventually morphed into revolutionaries and became Americans weren't the first people to arrive in the New World, or the first to try to conquer it. The Spanish and the French also tried their hands at making America their own. That's why we had to buy the Louisiana Purchase from France, and get Florida from Spain via treaty. But neither France nor Spain—which were both worldwide imperial superpowers at the time—could make much headway in North America. And according to author S.C. Gwynne, there was a simple reason their conquest stalled: The Comanches.

By the time the French and the Spanish were trying to claim territory in the plains, the Comanches had evolved into the most capable horsemen in the world. They had adapted conventional weaponry to the horse, and their total focus on waging brutal, violent war had forged them into the most effective and terrifying war machine on the planet. And every time the European powers tried to fight them, they lost, and lost badly.

In fact, the Comanches were the reason California and the West Coast were settled before the middle of the country. And as author Pekka Hämäläinen makes clear, one reason Mexico was so easily defeated by the United States in the Mexican-American War was due to the Comanches, who had spent the prior decades brutally stretching Mexico's fighting force to its limits.

The Comanche were unofficially at war with Texas for 40 years

The Comanche were already a vibrant and developed civilization in the 17th century, but when the Spanish introduced the horse to them everything changed. Within a few decades they were not only the most accomplished horse riders in the world, they were a powerful military force that began to assert dominance over the plains—they weren't called Lords of the Plains for nothing.

What's remarkable about a lot of U.S. history is how the wars between the Comanches and the United States are often not described as wars at all. But as author S.C. Gwynne makes clear, there's no wiggle room: The Comanches conducted a war against Texas that lasted nearly 40 years, stretching across its time as a Spanish possession, an independent state, and finally as part of the U.S. The Texas Rangers were founded in part to defend settlers against the Comanches, and quickly adopted the "total war" approach that the Native American warriors practiced.

But for decades, Texas couldn't stop the Comanches—in fact, they even expanded their territory into Texas on several occasions. It wasn't until Texas joined the United States and President Ulysses S. Grant made defeating the Comanches a priority that they were finally pushed back, setting off a series of events that culminated in their final defeat in the 1870s.

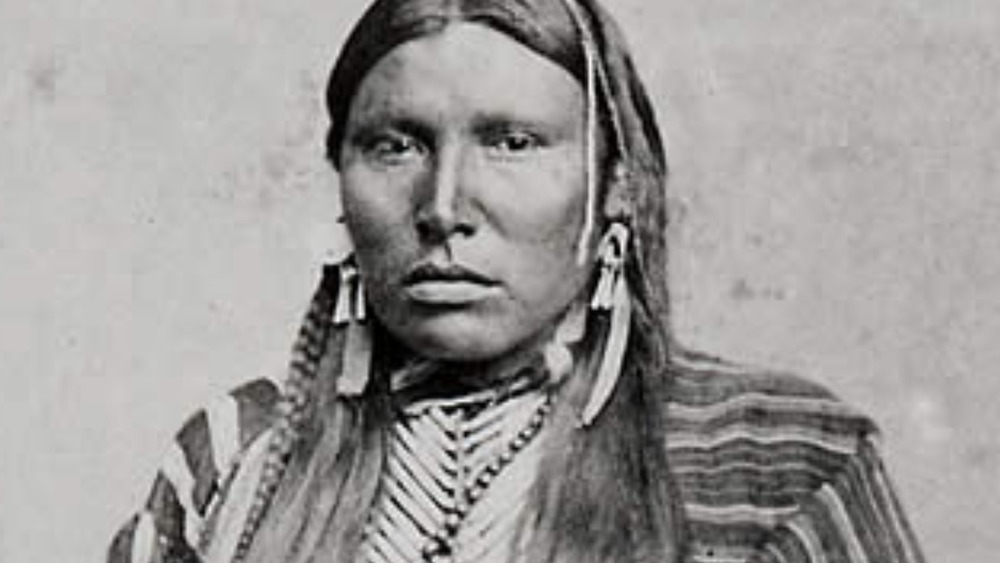

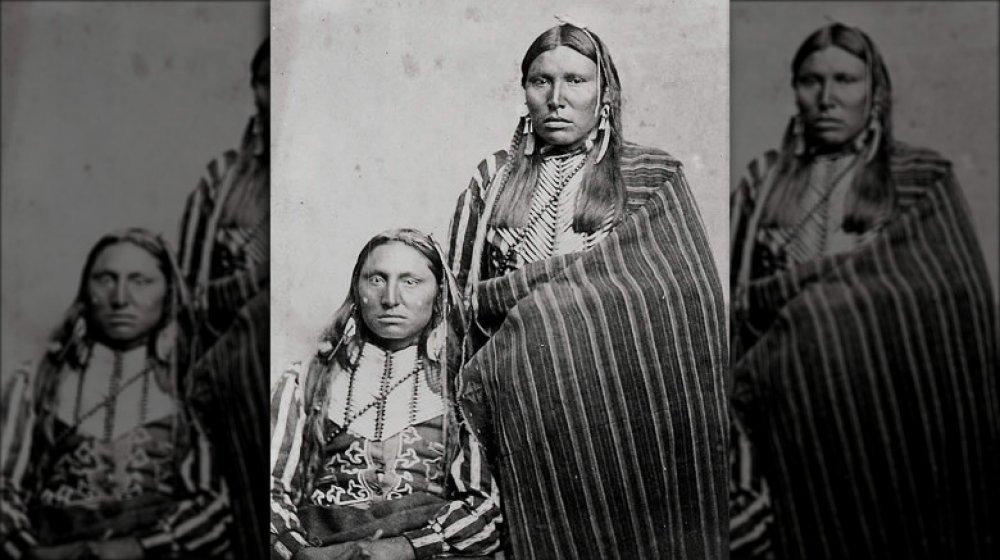

The last great Comanche Chief was half white

As Texas Monthly reports, a woman named Cynthia Ann Parker was kidnapped by Comanche raiders in 1836. She was assimilated into the tribe and eventually married and bore a son named Quanah Parker in 1852. By the time Quanah was an adult, the Comanche Nation was in its final death throes, and he was destined to be its last great leader.

As a youthful warrior, Quanah was the epitome of Comanche bravery and fierceness. Remarkably young for a chief, Quanah led a series of violent raids against American forces in 1871, when he was just 19-years-old. As The San Antonio Express-News explains, in 1874 Quanah gathered 300 Comanche warriors and launched a final assault on the American forces encroaching on the Comancheria, intending to drive them away once and for all as the Comanche had always been able to do. They attacked a trading post called Adobe Walls, where about 28 hunters had taken shelter. Instead of a shocking victory, it turned into a slog: A five-day siege that ended with the Indians retreating. They continued to raid and slaughter, however, and American forces pursued, burning their supplies and killing their horses as they went.

This broke the back of the Comanche Nation, and Quanah led his surviving warriors to surrender, agreeing to move to a reservation. Quanah proved to be a popular and capable peacetime leader, however, and spent the rest of his life serving his people as a peaceful Chief of the Comanche Nation.

Disease did them in

By the 1870s, the Comanches were finally being effectively resisted by American forces. There were several reasons the U.S. was having some success after decades of failure against the Lords of the Plains. The brutal fighting of the Civil War left the U.S. with an experienced and well-equipped modern fighting force, and President Ulysses S. Grant was determined to put an end to their power for once and for all.

But as Texas Monthly explains, there was another factor at work: Disease. As with many other Native American tribes, the more they traded and interacted with white settlers, the more they fell victim to diseases like smallpox and cholera. Having never encountered them before, they had no defense against them. Two widespread epidemics in 1816 and 1849 had reduced the Comanche population by half.

One reason the Quahadi band, led by the last great Comanche Chief, Quanah Parker, was still a formidable fighting force in the 1870s, in fact, is because they had always disdained any sort of peaceful contact with whites. Having shunned the settlers pushing west, they had avoided these plagues. This left them as one of the few remaining Comanche bands capable of resisting the U.S.'s march westward.

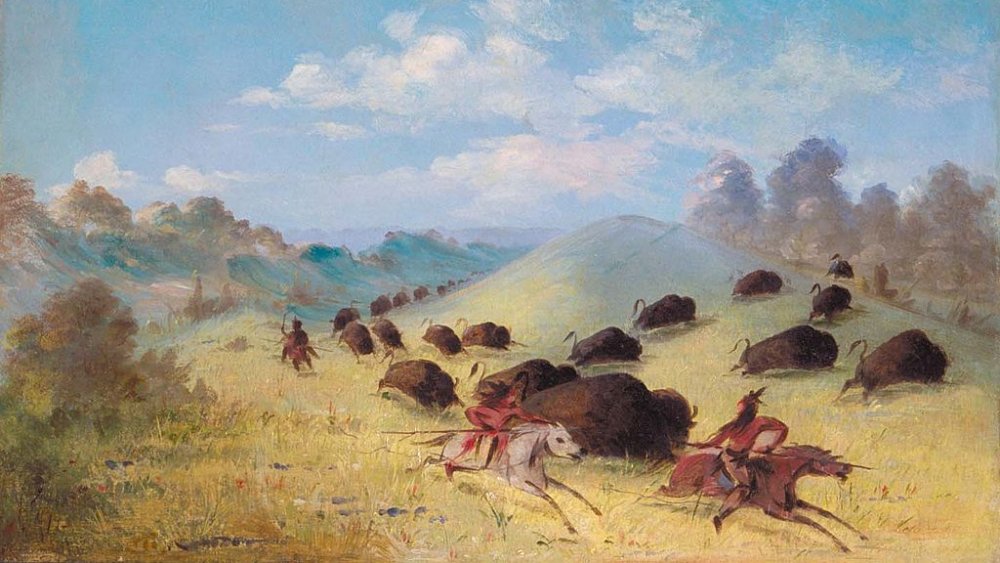

The U.S. fought the Comanche by killing buffalo

As noted by author Pekka Hämäläinen, one thing about the Comanches was almost unique in world history: They relied almost completely on exactly one food source, the buffalo. The buffalo were plentiful in the plains, and with their superior horse-riding skills the Comanche found it incredibly easy to hunt them. In fact, as NPR notes, you could shoot buffalo as they grazed and the herd wouldn't even run away. This made it possible to kill an incredible number of the animals very quickly and with little effort—as many as 3,500 could be killed by one man in a month.

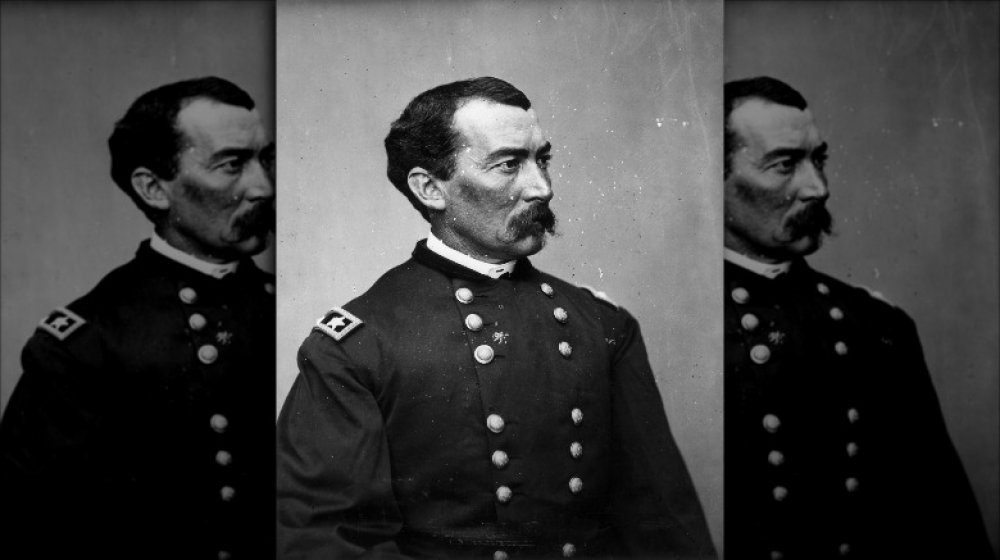

When the United States finally got serious about opposing the Comanches in the plains, the men in charge—General Phil Sheridan and General William Sherman—realized that this dependence was a strategic weakness. According to High Plains Public Radio, Sheridan is quoted as saying "You kill the buffalo, you destroy the Indian's commissary."

Killing buffalo became policy. Between 1868 and 1881, 31 million buffalo were slaughtered not for food or for any other purpose, but simply to destroy the Comanches' food source. And it worked. By 1874, the Comanches faced an almost total collapse of their civilization and way of life. A short time later, the last of the Comanches surrendered.

The lessons of the Civil War defeated the Comanche

The United States had been struggling with various Indian tribes for its entire existence. This tends to happen when you brutally and illegally displace a native population. But for a very long time the American effort to dislodge the Comanches was too scattered and unfocused to have any effect on the smooth military machine that was the Comancheria.

After the Civil War ended, the U.S. seemed weary of war. As noted by Smithsonian Magazine, when Ulysses S. Grant became president he promised to avoid war in the west and honor treaties with the Native American tribes. But his efforts at peaceful co-existence eroded in the face of political pressure, and he soon dispatched two of his most effective Civil War generals, Philip Sheridan and William Sherman, to finally pacify the Comanche and other tribes.

As the Chicago Tribune notes, Sheridan and Sherman were believers in the "total war" strategy that had defeated the Confederacy. Sheridan, who reportedly once said "the only good Indians I ever saw were dead" (he denied saying it), led a brutal campaign that continued even in the winter, sanctioned violence against women and children non-combatants, and slaughtered buffalo simply to starve the Indians. These horrifying tactics worked, and by the late 1870s almost every Native American in the plains lived on a reservation.