The Tragic And Scandalous Story Of 'Baby Doe' Tabor

Colorado and even western history isn't complete without the story of H.A.W. and Baby Doe Tabor, the infamous couple who were ridiculously rich and quite literally went broke overnight. But this isn't your typical rags-to-riches-to-rags story. The Tabors spent their millions on extravagant properties, expensive wardrobes, vacations, and sundries for themselves and their children. They were both the envy and the shame of Denver and beyond, beginning with each of their scandalous divorces and subsequent marriage.

Who was to blame? Horace Austin Warren "H.A.W." Tabor, whose stifled marriage to his boss's daughter turned sour when he struck it filthy rich and his wife insisted on saving every penny? Or Elizabeth "Baby" McCourt Doe, who left an equally unsatisfactory union to pursue happiness with the money man of her dreams? Theirs was an affair of the heart, but also an affair against the sanctity of marriage. And in the end, Baby got the short end of the karma stick after only a decade or so of reveling in riches and spent the rest of her life in abject poverty. Here is the heart-breaking story of Baby Doe Tabor, the woman who loved and lost.

Introducing Miss Elizabeth McCourt, aka Baby Doe

Elizabeth "Lizzie" McCourt was born in 1854 in Oshkosh, Wisconsin. She was named for her mother; one of her brothers, Peter, was named for their father. Peter McCourt Sr. was a profitable clothing merchant. By 1870, according to the census, the family included seven children in all. With four brothers, it is no wonder Lizzie sported an "independent spirit with a tomboy disposition" as a child, according to Legends of America. But she was so pretty with her cherub-like face, surrounded by natural blonde curls, that her mother prevented her from laboring too hard lest she mar her beauty and miss out on a promising marriage.

Shortly after winning figure skating contest held by her family's church, Lizzie met her future husband: Harvey Doe Jr. Although Harvey's mother was uncomfortable with her son courting a girl from a family "beneath" the financial status of the Does, Lizzie married the boy anyway in 1877. Harvey's father happened to own an interest in the Fourth of July Mine near Central City, Colorado (pictured), which seemed like a great place to start a new life. The newlyweds set out for Central City, where Lizzie set up housekeeping while Harvey worked the mine. And when the Fourth of July foundered, the determined Lizzie jumped in to help at the mine, a first for such a male-dominated industry.

Baby Doe's divorce from Harvey Doe

Harvey disapproved of his wife working in the mine, but Lizzie soon became a favorite of the other miners who began calling her "Baby." Notably, Lizzie never referred to herself by that name and possibly even found it offensive. Harvey, meanwhile, began drinking heavily. When he lost his job, as well as other jobs at other mines, the couple were forced to move around in search of "cheaper housing." Harvey eventually went looking for work in other mining camps and stayed gone for long periods of time. A bored Lizzie passed the time by touring the exciting downtown area and finally made friends with clothing merchant Jacob Sandelowsky, better known as Jake Sands.

Historians disagree on whether Sands was more than a friend to Lizzie, but there is evidence the two were romantically involved. When Harvey went back to Wisconsin without Lizzie, Sands stepped in to help her with groceries and other bills. The couple was sometimes seen together at the Shoo-Fly saloon. Author John Burke claimed the two were together as early as 1878, when Sands kissed Lizzie on the schoolhouse steps. He also was there when she gave birth to a stillborn son in 1879, leading to speculation the child was his. Lizzie did try to reconcile with her husband when he returned to Colorado, but after spying him entering a brothel (like the one pictured) she successfully filed for divorce in 1880.

Baby Doe's life in Leadville with Jake Sands

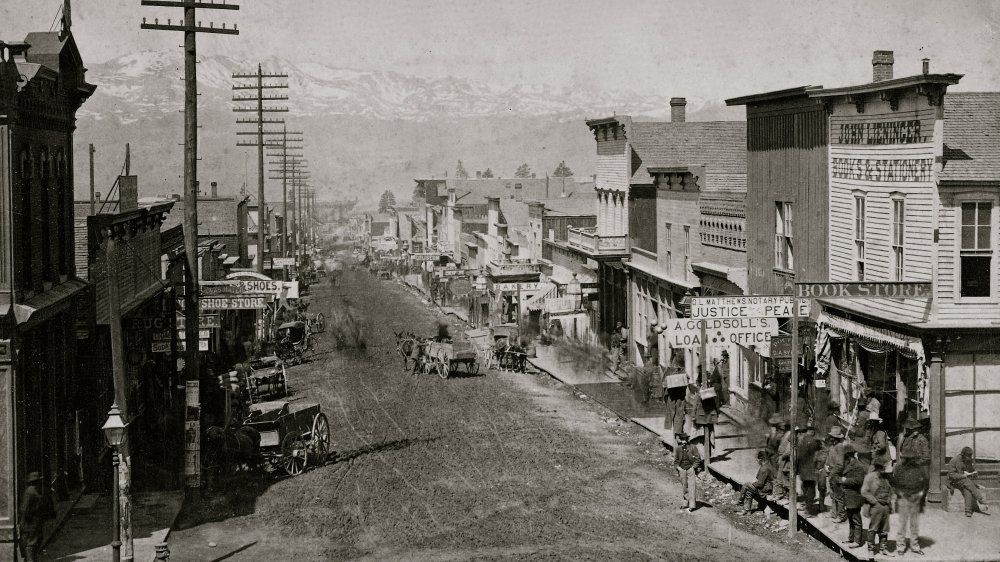

For Harvey Doe, the breakup of his marriage was devastating. He never achieved any greater career than that of a day laborer, returning to Wisconsin and eventually remarrying. He also maintained contact with Lizzie for much of the rest of his life. Lizzie, meanwhile, willingly moved with Jake Sands to Leadville, a rollicking silver boom town some 80 miles southwest of Central City. For a time she worked in Sands' new store, which was located in the newly-opened Tabor Opera House.

It is notable that the 1880 census shows the couple living at two different addresses, according to Legends of America, because Sands respectfully "arranged for Baby Doe to stay at a boarding house." He also hoped to marry Lizzie, writing her love letters which she kept until her death. Also notable is that Sands' landlord at the Tabor Opera House was none other than Horace Tabor, who likely met Lizzie at the store since he was living in a suite upstairs. Sands and Tabor also shared an interest in two mines. The more Lizzie got to know Tabor, the less she warmed up to Sands. "I was very sad thinking you would not open your door for the man who loves and worships you," Sands wrote to Lizzie. "Is it possible that you have learned to hate me? I can not for one moment believe it."

H.A.W. Tabor, the man of Baby Doe's dreams

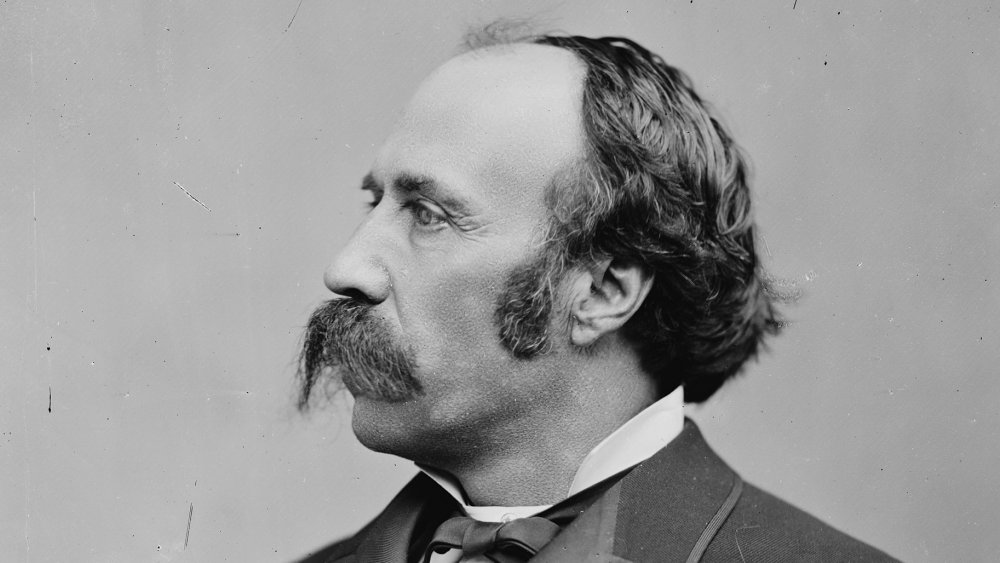

Horace Tabor was born in Vermont in 1830—some 24 years before Lizzie. A trained stone mason-turned-farmer, Tabor married Augusta Pierce in 1857 and had one son, Maxcy, when the family moved to Leadville's California Gulch in 1860. It had been hard going: the Tabors began as hard-working, humble storekeepers who occasionally grubstaked miners in hopes of making some profits off of mining. As one of the first women in the camp, Augusta served as postmistress but also laundress, cook and banker. By saving every penny they made, Augusta steered the couple towards upper middle-class citizenship. But when one of Tabor's grubstaked mines paid off, he was soon pulling in $50,000 per month.

Tabor was immediately giddy with his newfound wealth, spending money like it was going out of style. Western Mining History says Leadville benefited greatly from the newspapers, bank, hotel and opera house Tabor built, and he was soon elected mayor of Leadville as well as Lieutenant Governor of Colorado. Augusta, however, enjoyed neither her husband's new station in life, nor his millions. The Tabor's relationship was soon quite precarious, with Horace flaunting his money while Augusta refused to change her lifestyle. So when the beautiful and bubbly Baby Doe came into view at Sands' clothing store right there in the Tabor Opera House, Horace Tabor could not help but notice her.

Baby Doe's love, marriage, and lavish life with Tabor

When Lizzie met Horace Tabor in 1880, several wheels were set in motion. First, Lizzie dropped Jake Sands like a hot potato. Next, Tabor began an illicit affair with Lizzie, "ferrying her back and forth from Denver to Leadville so they could be together." When the affair eventually became known to the public, Horace quietly secured a divorce from Augusta in 1882 and immediately married Lizzie in St. Louis, Missouri—in secret. Six months later, hoping to avoid a scandal, the publicly-known Tabors married again in Washington, D.C. after Tabor was appointed Senator. President Chester Arthur was in attendance as Lizzie married her man in a $7,500 dress.

How did high society react to Horace Tabor's divorce and subsequent marriage? Not well. "The records of his unsavory divorce suit are scarcely dry when he is married, with vulgar display, in Washington city," spewed the Cincinnati Enquirer (per Center West). The Rocky Mountain Herald felt the same way, recommending Tabor be "severely censured by every respectable institution in the land." Blinded by love, the Tabors paid little attention to the press, choosing to throw fancy parties at their Denver mansion even as Denver society actively shunned the scandalous Baby Doe. Augusta (pictured), who had preferred to sleep in the simple servant's quarters when she was mistress of that mansion, moved on with her life and relocated to California.

The children of Baby Doe and Horace Tabor

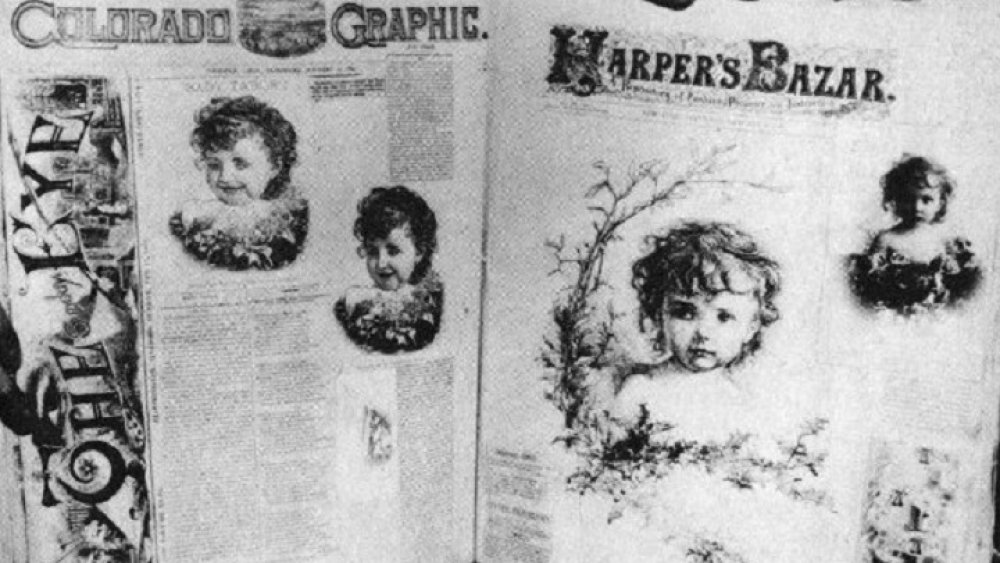

Within a year of the notorious Tabor marriage(s), Lizzie became pregnant with the couple's first child. Born in 1884, Elizabeth Bonduel Lily Tabor was every bit as striking as her mother was with golden curly hair, large beautiful eyes and creamy skin. Authors Glenda Riley and Richard Etulain verified that Lily was christened in a $15,000 gown, but also that Lizzie preferred staying home with her daughter rather than hire a nanny. Lizzie also adored having Lily professionally photographed often, to the extent that engravings of the child appeared in both Harper's Bazar and Colorado Graphic.

Lizzie gave birth to another child in 1888, a boy who lived but a few hours. Her grief must have echoed the loss she felt from her first stillborn baby. But by the time the Tabor's third child, Rose Mary Echo Tabor, was born in 1889 the couple was virtually out of control with their money. When politician William Jennings Bryan visited the Tabor mansion shortly after the baby's birth and commented that "her voice has the ring of a silver dollar," the Tabors whimsically added "Silver Dollar" to the child's name. Like her sister, Silver Dollar was dressed in the fanciest of clothing and was also photographed on numerous occasions.

Baby Doe's 'lavish' life with Horace Tabor

Everybody loves capitalizing on the Tabor's outrageous spending habits, according to Colorado Women's Hall of Fame, from the $54,000 ($1.5 million today) "pretentious" mansion Horace purchased in 1886 in Denver to their reputation as "The Silver King and Queen." They say the Tabors used their millions to buy expensive clothing, host grand parties, and erect monuments to themselves such Denver's Tabor Grand Opera House. But the couple also donated a lot of land and money, even as snobby Denver citizens continued looking down heir noses at them. Horace was perhaps sympathetic with his wife when he wrote, "My dear, brave little Baby, so trusting, so hard-working-and always so cheerful! Your love has been the most beautiful thing in my life."

Jennie Sandelin, who worked for the Tabors, remembered how Mrs. Tabor "was not extravagant in her dress," and she loved Jennie's tomato soup. She also said Mrs. Tabor sometimes instructed her to tell callers the lady of the house was out. Lizzie seemed to enjoy staying in with her children and working on her very personal scrapbooks, some of which survive today and illuminate her thoughts and feelings. She also supported the women's suffrage movement by donating office space for the cause. And if Denver's upper crust refused to come to their parties, the Tabors could always play host to important people they knew who passed through town.

The loss of the Tabor fortune

At their peak, Horace and Baby Doe Tabor (pictured) were worth around $9 million dollars—a whopping $257,419,780.22 today. As Lizzie lovingly tended to her children and her beloved scrapbooks, Horace Tabor continued climbing the ladder of wealth. No longer a Senator, he campaigned to get back in the Senate and spent "huge sums" of money towards his campaign to be elected as Colorado's governor. And, he was forever investing more money into mines and other businesses. Call it fate, but in about 1893 these attempts at further wealth—including several mines—began failing Tabor. Later that same year, Congress repealed the Sherman Silver Purchase Act that had helped make Tabor so rich.

Almost overnight, the Tabors literally went broke. Central City Opera says Horace Tabor was so enamored by his fortune that he stubbornly held onto his mines in the hopes the price of silver would go back up. He also made more investments which also flopped. Refusing to declare bankruptcy, Tabor continued trying to pay his debts by purchasing a mine near the town of Ward and working it himself. But he was now in his late 60's, and had not saved a dime of his millions. Slowly but surely the Tabor properties were lost, including the illustrious Tabor Block and the family home.

The Tabors lived in abject poverty for five years

Although the Tabors managed to live in their luxurious mansion at 1260 Sherman Street until 1896, Horace continually struggled to keep the family afloat. He was forced by his circumstances to go back to working as a common miner for others in Leadville and Cripple Creek. Lizzie, meanwhile, did what she could to "stave off poverty" by handling the couple's business dealings in Denver. At last, however, even the mansion was lost. Legends of America says the Tabor family rented a small cottage, but were eventually forced to live in the fabulous Tabor Opera House which was being managed by Lizzie's brother, Peter McCourt.

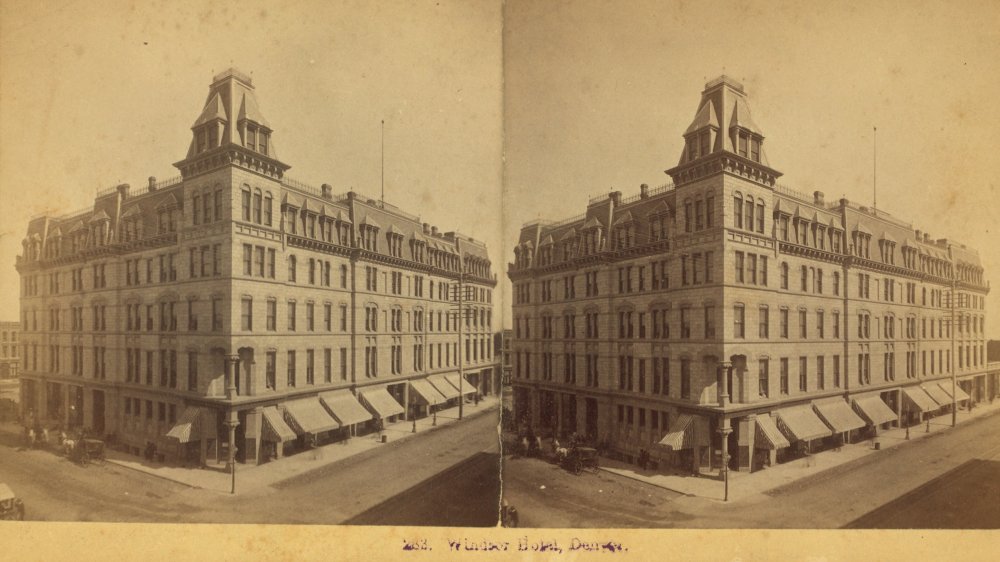

The family had moved again, to the Hotel L'Imperiale, when Tabor's sympathetic and affluent friends got him appointed as Postmaster of Denver. The following year, however, Horace suffered an attack of appendicitis. He was taken to the Windsor Hotel (pictured) as Lizzie was summoned to his side. They say just before he died, Tabor advised Lizzie to hold onto the Matchless Mine in Leadville, which had produced some $7.5 million dollars for the Tabor fortune. As much as he had been shunned, 10,000 people attended Tabor's funeral when he was buried in Mt. Calvary Cemetery, and flags were flown at half-mast in honor of the late millionaire.

Life for Baby Doe after Tabor's death

Horace Tabor's death had a profoundly devastating affect on Lizzie. She quite literally had nobody to turn to. Back in 1896, she had already appealed to her brother Peter, who, the National Park Service says, callously turned her away. "I haven't any money to spare," he told her, "and even if I could, you'd only throw it away on some silly extravagance." At least Lizzie could slyly ask for Peter's help through her daughters, to whom he did occasionally send money. And she would have continued working the Matchless, except the mine was auctioned in 1900. Lizzie eventually returned to Leadville anyway, where she and her daughters were allowed to live on the Matchless property (pictured) by the new owners.

Life was truly hard for Lizzie and her girls. It is guessed that she sold some of her belongings and "worked odd jobs" in her attempts to keep afloat. One of her worries was being able to keep the last of her keepsakes in storage in Denver, which consisted of "clothing, hats, books, journals, dinnerware, silver tea sets and even her children's toys." In 1907, she penned a desperate letter to mine superintendent Sam Duran, asking for a loan of a mere $17.00 to pay "on some things of the children's" and offering "a ton steel bucket" as collateral. Determined to make it on her own, Lizzie refused charity and truly believed she would eventually pay for the items she charged on account in Leadville.

What happened to Baby Doe's children?

In her efforts to keep afloat, Lizzie Tabor even resumed communications with Jake Sands, who sometimes loaned her money but never rekindled their romance. Fed up with her shameless mother, Lily finally appealed to her Uncle Peter for money to return back east. In 1908, she married her first cousin, John Last. Silver Dollar, meanwhile, became a bit of a wild child in Leadville where the Aspen Daily Times says she was known as the "pet of the camp." But she also made attempts at writing, penning the song "Our President Roosevelt's Colorado Hunt" and presenting it to the former president in 1910. Mother and daughter were back in Denver when Silver also attempted to regain some of her father's property which had gone into receivership.

Lizzie also kept in touch with the remarried Harvey Doe, who met up with her when she and Silver visited Lily in 1911. Harvey promised to come to Colorado and help Lizzie. But he never did, and died in 1921. Back in Denver, Silver continued writing for newspapers and even penned a novel, Star of Blood. She also took a stab at acting, appearing in 1914's silent movie, The Greater Barrier. A few years later she moved to Chicago in her further attempts at acting. Instead, she became swept up in drugs and alcohol, dying from an accidental scalding in 1925. Lizzie denied her daughter was dead, saying Silver was now a nun in a convent.

Baby Doe's sad end at the Matchless Mine

Following Silver Dollar's death, Lizzie Tabor continued living out her life at the Matchless Mine. Ever proud she refused offers of charity, choosing instead to practice Catholicism and write of "her dreams, memories, and visions." Those seeing her wandering around Leadville with rags on her feet supposed Baby Doe had gone mad, but at least one writer maintained "her mind was still strong and hard." When Warner Brothers produced Silver Dollar in 1932, a movie based loosely on the Tabor story, nobody should have been surprised when Lizzie turned down the $1,000 offered to her to attend the premiere.

In March of 1935, Lizzie was found frozen to death on the floor of her cabin. She was buried in Denver. When Lily was notified of her death, she denied the woman was her mother. With no family to claim it, Lizzie's stored belongings, including her fabulous wedding dress, were auctioned off in Denver but fortunately ended up at Colorado's historical society. In 1985, years after The Ballad of Baby Doe became a popular show in Central City, Lizzie was inducted into the Colorado Woman's Hall of Fame. Today the Matchless Mine gives tours that include her cabin, and is undergoing repairs. Likewise, Leadville's Tabor Opera House—the last surviving structure of the Tabor empire—is also getting needed restorations. Lizzie would like that.