The Tragic Story Of Dancer Isadora Duncan

It can be difficult to really get the full scope of Isadora Duncan's tumultuous life. She was a pioneering dancer with an outsized personality. Duncan was someone who pushed boundaries and changed the face of her art, which was considered so shocking that it put her at the center of gossip and frayed friendships. Even her sudden death in an automobile accident seems like a sad end that is still in tune with her often sudden, impulsive life. She was a spectacle.

Duncan didn't get there easily. Her story is rife with tragedy from the very beginning. According to Biography, she was born in 1877, to a family on the brink of collapse. Her parents divorced soon after Isadora was born, broken apart by financial deception and personal dalliance. Her single mother struggled to keep the family afloat, while Isadora eventually dropped out of school at a young age.

Through determination and skill, she found a place for herself in the dancing world, but at the cost of raising many eyebrows and shocking quite a few traditionalists. Yet, tragedy still dogged her, affecting not just the freethinking, free-loving Isadora Duncan, but her family and friends as well.

Isadora Duncan grew up amid family strife

Isadora Duncan's troubles started not long after her birth in 1877. She was the youngest of four children born to Joseph Duncan and Mary Gray. As related by Time and the Dancing Image, Joseph was an inventive man, working variously as a newspaper publisher, real estate agent, and banker. Unfortunately, he was also a cheat. Shortly after Isadora made her first appearance, Mary discovered that he had been using bank money to finance his own private stock investments. Though he escaped legal consequences, it was a close call that could have landed Joseph in jail.

Joseph Duncan was also apparently a serial cheater, a fact that was clear to his wife. Mary divorced him and took the children to live in Oakland and San Francisco. Between taking on work as a seamstress and piano teacher, Mary likely fretted about the constant bills and rent payments that were always due. According to The Journal of Religion, she also read aloud texts written by atheist intellectual Robert Ingersoll, whose freethinking ways may very well have influenced Isadora as she grew into adulthood.

For her part, Isadora Duncan began to work at a young age. She dropped out of school by age 10, per the Isadora Duncan Dance Company. Along with her sister, Elizabeth, she earned money by teaching dance to local children. This is apparently where she turned rather sour on ballet, once saying it was little more than "affected grace and toe walking."

Duncan butted heads with the ballet establishment

By the time she had turned 18, Isadora Duncan was ready to leave California, The New York Times reports. With her mother in tow, she made her way east and joined stage director Augustin Daly's company. She thought that she was ill-used, even as a relatively new member of Daly's group. She got pretty bold when she reportedly asked Daly, ”What's the good of having me here, with my genius, when you make no use of me?” Eventually, she moved to New York and found some success as a dancer, though her reputation didn't really take off until she moved to Europe in 1899. There, her boundary-pushing began to draw interest. She soon began performing to sold-out crowds.

Her sense of self was blatantly egotistical, but Duncan was primed to push back against the dancing establishment. To her mind, it had become overly conservative, a musty ode to the way things had always been. According to NPR, ballet has been around since the Renaissance. To Isadora Duncan's mind, the art of dance had only calcified since then. Things desperately needed to change. In her autobiography, My Life, her visit to Russia's Imperial Ballet School exemplified her feelings about the dance. "The great, bare dancing rooms [...] were like a torture chamber. I was more than ever convinced that the Imperial Ballet School is an enemy to nature and to Art."

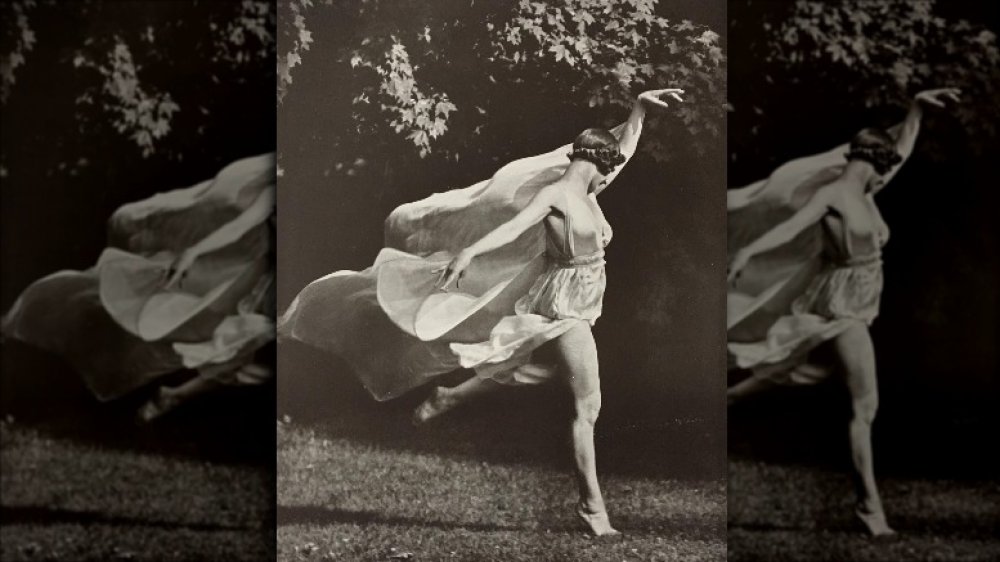

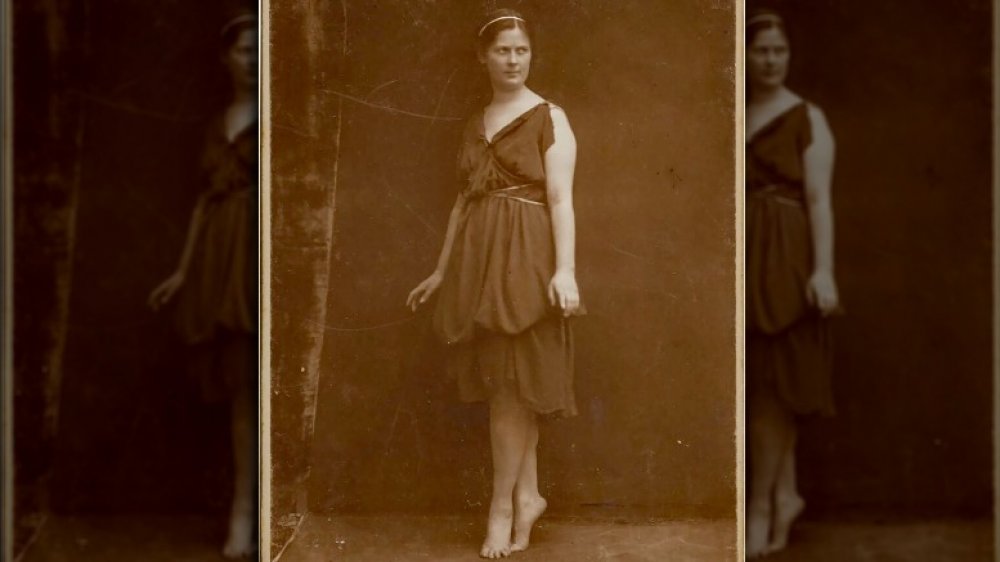

Isadora Duncan's dance attire shocked audiences

Isadora Duncan's dance costumes used unstructured, free-flowing silhouettes that also emphasized the curves of the dancer. Nineteenth-century audiences who were used to the aesthetic of ballet were taken aback by what they saw. Then again, there were plenty of free-thinking, modern lovers of dance who were intrigued and perhaps a little titillated by Duncan's look.

This free love approach actually wasn't out of line with the history of dance, the National Museum of Women in the Arts reports. Ballet had already gained a bit of a racy reputation, with many assuming that the dancers were loose women benefiting from lecherous "patrons." Duncan, who generally wasn't bothered by petty concerns like conventional morality, actually updated the revealing ballet look. She became somewhat notorious for her Grecian-style dresses she wore during performances, made out of sheer fabric that clung to her form. For viewers used to the Victorian standard of dress, which often covered and restricted women's bodies, Duncan's fashion could be astonishing.

Duncan wasn't just doing this to shock people and gain notoriety. According to The New Research in Dress History conference, it was all part of her deeply-held beliefs about the importance of dance and self-expression. For her, dance could not develop and grow into a richer art form if its practitioners were always bound up in corsets and toe shoes. The barefoot, chiffon-wearing dancers of Duncan's work represented her drive to break dance out of its rut and into a brave new artform.

Duncan was probably bisexual in a homophobic time

The world of Isadora Duncan's time was not kind to LGBTQ people, though the situation may have been more complex than you think. The Victorians who preceded Duncan certainly had a complex view of same-sex love and attraction and often gave artists, in particular, a bit of a pass, the BBC reports. Yet, homophobia was still rampant. Pride celebrations would have been a wild, seemingly unattainable dream for anyone of the time. Gay people of this period were routinely ostracized, imprisoned, and subject to painful conversion therapies meant to turn them straight, History says.

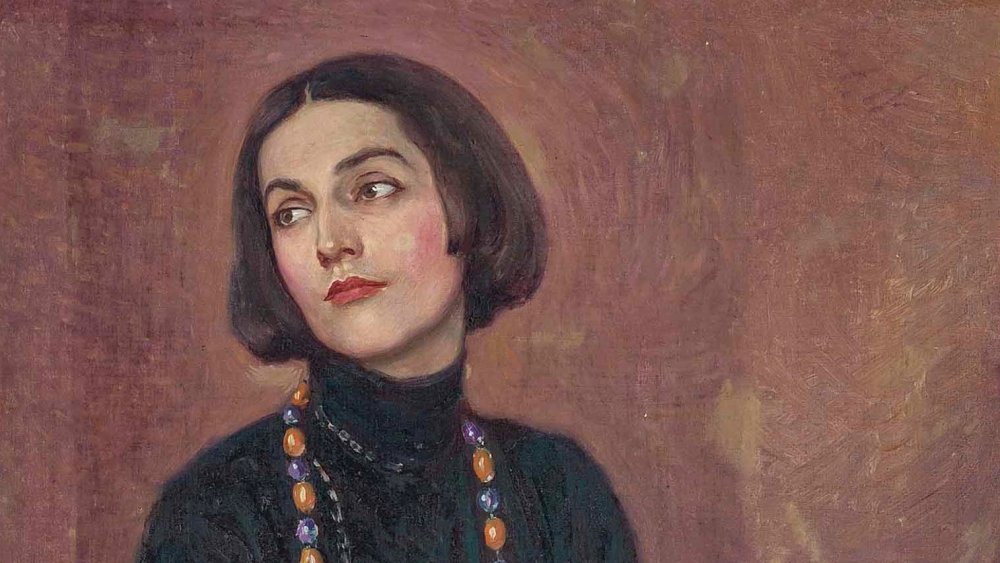

Duncan, who routinely flouted social conventions throughout her life, carried on affairs with both men and women. As per the Advocate, her most well-known alleged affair, with writer and socialite Mercedes de Acosta, took place after Duncan's only husband, Russian writer Sergei Yesenin, had left her and then committed suicide. The pair had already known each other for some time, though it's unclear when, exactly, their physical relationship began.

According to That Furious Lesbian: The Story of Mercedes de Acosta, they first met in 1917. Isadora eventually wrote a poem about Mercedes, romantically referring to what she liked to do to the other woman's body. The pair also exchanged letters with each other, sometimes with overtly romantic sentiments. In other accounts, Mercedes more explicitly referred to what the two women did together to express their affection, making it clear that they were sexually and romantically entangled for a time.

Isadora Duncan was an outspoken communist

Though anti-communist sentiment would not be at its high in the U.S. until Senator Joseph McCarthy's peak in the 1950s, it still wasn't popular to proclaim communist sentiments in Isadora Duncan's time. For Duncan, her allegiance to the cause was yet another part of her beliefs that set her apart. The New York Times reports that, by the 1920s, Russian political thought was beginning to spread throughout the world. While some cottoned to their Communist ideals, others reacted with anti-Bolshevik sentiment.

In the introduction to her autobiography, My Life, it's reported that Duncan said her work would have been banned in the United States if she'd discussed her "Communist years" more openly. Yet, she did discuss it somewhat, writing that it was "No wonder that I felt inclined to become a Communist when I so often had exemplified for me the fact that for a rich man to find happiness was like Sisyphus trying to roll his stone uphill from Hell."

Other reports indicate that she wasn't shy about stating her commitment from the stage. As related in Dance and Politics, she once ended a performance by producing a red scarf and waving it about, saying "This is red! So am I!" Some accounts maintain that she also exposed herself in the same incident, but that may very well have been a rumor that played into Duncan's already larger than life persona and often scandalous behavior.

Duncan's children met a tragic end

Though she frequently shied away from social conventions like marriage, Isadora Duncan apparently wasn't against becoming a mother. She had three children, all out of wedlock, and appeared to have been a doting parent when she wasn't busy working and traveling. All of her children, however, were doomed to an unfortunate end.

Duncan's first child, Deirdre Beatrice, was the daughter of theater designer Gordon Craig, per Done Into Dance. Her second, Patrick, was the son of Paris Singer, himself the son of sewing machine tycoon Isaac Singer. Duncan skirted outright censure by saying that they were her adopted children, but she remained a single parent. Tragedy struck in 1913, when a car carrying the two children and their governess, Annie, accidentally drove into the River Seine in Paris. The driver survived, the San Francisco Call reported, but Patrick, Deirdre, and Annie drowned. Duncan was obliterated by grief.

After a 1914 affair with sculptor Romano Romanelli, Barefoot Dancer says, Duncan learned that she was pregnant. She happily accepted the news, believing that the new child was the spirit of Deirde or Patrick returning to her. In August 1914, she gave birth to a son who lived for only a few hours. "I believe that in that moment I reached the height of suffering that can come to me on earth," she later wrote.

Duncan's feminism put her at odds with society

The journal American Studies reports that Isadora Duncan's freewheeling aesthetic, both on and offstage, was all part of a greater artistic move towards self-expression, compared to the repressive, patriarchal attitudes of the Victorians. For Duncan, women were meant to move their bodies freely, without consideration for anything other than the higher pursuit of art. Things like traditional marriage and restrictive sexual conventions would only hold Duncan and other women back.

Surprisingly, Duncan, who would eventually become notorious not just for her free-flowing aesthetic, but also her dramatic personal life, wasn't keen on sexualizing her dance performances. Her body, and the bodies of her dancers, were instead meant to represent a whole artistic impression. They weren't mean to cater luridly to the male gaze as some earlier dancers were rumored to have done. In her 1903 lecture, "The Dance of the Future," she said that her dancers "will dance not in the form of a nymph, nor fairy, nor coquette but in the form of a woman in its greatest and purest expression."

Duncan officially trained only female dancers. The assumption that her work could only be danced by women held strong for many decades after her death. In 1982, The New York Times reported on what was still the odd occurrence of a man dancing Duncan's choreography, more than 50 years after her passing.

Duncan's only husband mistreated and left her

In 1922, Isadora Duncan married poet Sergei Yesenin, who, at 26, was 18 years younger than the 45-year-old Duncan. It was to be a difficult relationship, though it was the only time the free-love Duncan had bothered to marry anybody.

According to The New York Times, the relationship was an utter disaster, almost from the very beginning. Yesenin spoke only Russian, while Duncan knew only a few words in his language. Yesenin also struggled with alcoholism, often becoming violent and abusive towards his wife. He reportedly embarrassed her in public, going so far as to say, "Woman very old!" when he was particularly upset with her. The pair moved to different locations across Europe, causing scenes wherever they went. Observers and friends noted the utter mess they left behind them, which often included damaged hotel furniture produced during yet another row between the couple.

According to the introduction to My Life, Yesenin had even thrown himself through a plate glass window once. Hounded by debt, they moved back to Russia, where Yesenin left Duncan after only nine months of marriage. "I married [her] for her money and for the chance to travel," he said, per The New York Times. Two years after the split, he was found in Leningrad's Hotel Angleterre, dead of an apparent suicide.

Friends grew sick of Duncan's shocking ways

As Isadora Duncan grew older, her oversized personality and impulsive ways grew harder to ignore. For her friends, Isadora's escapades and tragedies began to pile one upon the other, until a friendship with her began to seem more like a job than a pleasure. The New York Times maintains that she had grown "sexually rapacious" and emotionally sloppy. Friends stepped in to support her, but as the drama continued, many stepped away.

A 1927 New Yorker feature on her unflinchingly illustrates some of the changes faced by Isadora Duncan. "Her flesh is worn, perhaps by the weight of laurels," says the profile, perhaps trying to make up for the harsh words by throwing in some accolades. Ultimately, however, her ambitions and her life were too grand for the simple friendships enjoyed by others. "She has had friends," wrote the New Yorker, but "what she needed was an entire government."

Isadora Duncan's later life was plagued by debt and personal drama

Isadora Duncan's free-spirited life eventually left her with heavy debts and a trail of broken or complicated relationships. She moved continually, sometimes staying in apartments paid for by her remaining friends, according to The New York Times. When she had money, Duncan seemed unable to think of the future, and instead spent her constantly evaporating funds on grandiose nights out and indulgent purchases. When the money ran out, she wasn't above skipping town or, on one occasion, somehow getting a railroad porter to pay for her deluxe dinner.

Her last few years were also peppered with sexual relationships that never seemed to morph into anything solid. She had affairs with men and at least one woman, Mercedes de Acosta. By 1927, the New Yorker reported, she had begun to talk of writing her memoirs. Surely, she must have reasoned, a life as dramatic and uncompromising as hers would make for a compelling read. Isadora Duncan and her overburdened friends must have also hoped that it would make her enough money to stabilize her careening life.

Duncan struggled with alcohol

As she grew older, Isadora Duncan became notorious for her public drunkenness, though her most loyal friends often insisted that she was fine. Others were not so charitable. A young George Balanchine, quoted in The New York Times, saw her perform in the 1920s and came away thoroughly unimpressed. He viciously said that she was "a drunken, fat woman who for hours was rolling around like a pig."

Another observer, choreographer Frederick Ashton, also saw that she was drinking heavily during that decade, The Guardian reports. It was so bad, he reported, that her stage performances were beginning to visibly suffer as Duncan deteriorated. Soon enough, she became notorious for getting soused in public and embarrassing herself.

Others took advantage of Isadora Duncan's propensity for getting tipsy. According to Zelda Fitzgerald, when Duncan was carrying on at a Paris cafe, Zelda used the distraction to steal a pair of car-shaped salt and pepper shakers. Zelda herself wasn't a fan of Isadora, who may have carried on an affair with Zelda's husband, the writer F. Scott Fitzgerald. Reportedly, Zelda was so furious when he paid court to Duncan at yet another cafe that she flung herself down some nearby stairs to draw his attention. Isadora Duncan, it seems, couldn't help but attract dramatic people to her side, whether they wanted to be there or not.

Isadora Duncan met a sudden and shocking end

By the time she met her final day, Isadora Duncan had already dealt with failed relationships, tragic deaths, financial instability, and what appeared to be a growing problem with alcohol. Yet, it was to be a sports car that spelled her ultimate doom.

It was September 14, 1927. According to History, Isadora was in Nice, France. She was dressed to impress, or at least dressed dramatically, with an enormously long red scarf trailing from her neck. A newspaper account from the time claimed that the color of her neckwear was a reference to her communism. Either way, it's clear that Duncan wanted to make an impression on the people who were watching the still-famous, if somewhat fading, American dancer.

Duncan reportedly told her friend, Mary Desti, "Farewell, my friends. I go to glory!" However, The New York Times reports that writer Glenway Wescott later said that Desti confided in him, admitting that Isadora said, "I am off to love." Desti found this embarrassing, as it seemed like Duncan was yet again telling everyone about her sexual escapades. As the car began to move forward, one end of the scarf snaked down and around the rear axle and wheel. In a freak accident, Isadora Duncan was jerked from the open cab and briefly dragged along the cobblestones before the driver stopped. She died almost instantly of a broken neck. Later, writer Gertrude Stein, apparently unaffected by Duncan's abrupt demise, mordantly remarked that "affectations can be dangerous."