Strange And Bizarre Ways Halloween Has Been Altered

Every child in America — as well as much of the rest of the world — knows what Halloween means. Come October 31, you can expect to dress up as your favorite character or spooky thing, run around your neighborhood with your friends, and get a bag full of candy that you can eat until you're sick. Or else you might go to a party and play fun games like bobbing for apples and dance to "Monster Mash." If you're older, it might mean trying to get laughs at a party with the dumbest pun costume, or other kinds of attention with the sexiest costume. Or maybe you're just at home watching scary movies and answering the door when the little ones come by.

You might think it's always been this way, but that's definitely not the case. Here are just some of the many ways Halloween has changed in past centuries, and how it continues to change even today.

Banning dangerous and offensive costumes

For most people, the custom associated with Halloween more than any other is dressing up in costumes. You know, the costume custom. Dressing up is so integral to the day that many houses institute a "no costume, no candy" rule for trick or treat. For many people, it's a time to let their imaginations run wild for who they want to be for a single, spooky night. But, as Mental Floss records, at some schools and other public places, limits have been imposed upon what you can and can't dress as for Halloween. In some instances, these restrictions make sense: You shouldn't be able to dress as an offensive racial stereotype, and in fact, your costume shouldn't be just "a person of a different race" like that's the same thing as a vampire or a unicorn. Likewise, in this era of active shooter drills, schools are probably smart to restrict the presence of toy weapons or long coats that might be (and have been) used to conceal firearms.

Some choices are a little stranger, though. While it's not too much of a stretch to see why an elementary school might ban ghosts or witches as being too scary for small children, the choice to forbid superhero costumes as too scary seems both a step too far and a choice that will be incredibly unpopular among kids who like, you know, literally the most popular movies of all time.

All tricks, no treats

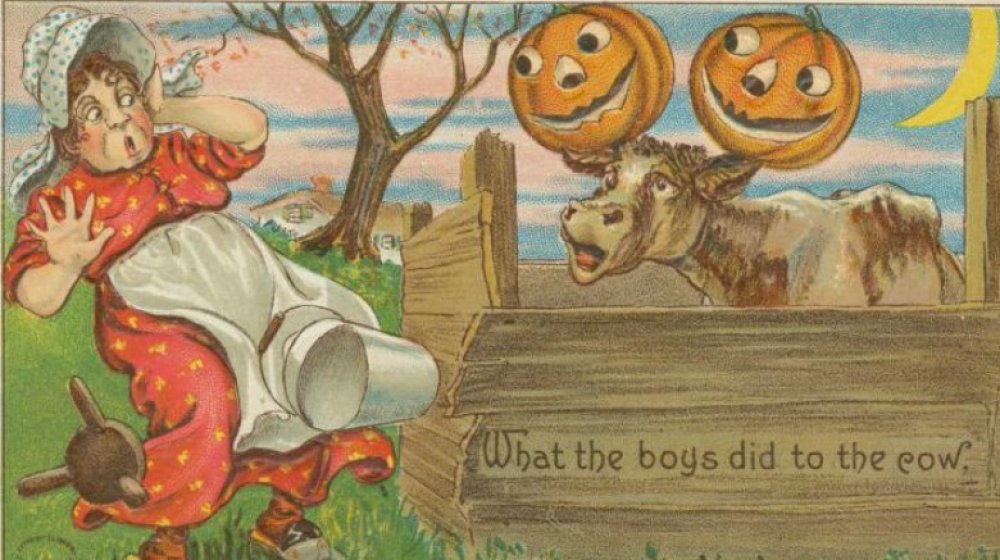

Although the traditions behind the Halloween practice of trick-or-treating go back hundreds of years, it was not always the most common way to celebrate October 31. According to History, when Irish and Scottish immigrants brought Halloween traditions with them to America in the 1800s, it wasn't the idea of kids in spooky costumes going around collecting treats. Rather, it was troublemaking teens running around with carved turnip lanterns pulling pranks, committing vandalism, and engaging in some light violence.

Common pranks included scaring people by pulling cabbages through fields so that they looked like they were moving on their own, removing manhole covers, deflating tires, filling houses with acrid smoke via the keyhole, and even putting stuffed dummies on railroad tracks to freak out train engineers. Worse, kids in urban areas might set fires, break windows, trip pedestrians, cover people in flour or ashes, and, most dangerously, wax streetcar tracks, causing dangerous crashes.

The Great Depression was the height of these kinds of dangerous pranks, and it was in the 1930s that civic groups began trying to counterprogram these kinds of activities by introducing safer ways for young people to engage with the holiday, including Halloween parties and trick-or-treating. It mostly worked, but in some areas of the US, the night for pranks and vandalism just got moved to October 30, known as Mischief Night, Goosey Night, or Devil's Night.

Spoiling Halloween fun, legally

While in the times before World War II, Halloween celebrations might have been tiny whirlwinds of lawlessness for youths who wanted to set fire to their teacher's porch or whatever, in more recent times, the law has begun to crack down on what is and isn't acceptable behavior on All Hallow's Eve. Avvo Stories features a list of laws passed in specific towns in recent years that could easily cramp someone's Halloween style. For example, several cities have ordinances that prevent you from wearing a mask or other costume elements that might cover your face, such as beards, with the idea that some people might take advantage of such concealment to commit crimes. In Belleville, Illinois, the law specifically states that no one over 12 can wear a mask. In Newport News, Virginia, no one over 12 can trick-or-treat at all.

In some cases, specific costumes are legally banned, such as nuns, priests, rabbis, or any other clergy members, as these may be offensive to observers of these religions. Also catering to the religious crowd is the Rehoboth Beach, Delaware, law that forbids trick-or-treating on a Sunday. A town in France banned clown costumes except for those with written permission from the government in 2014, and Hollywood, California, imposed a $1,000 fine for the use of that most harmless tool of vandalism, Silly String.

Trick-or-treating used to be about Christian charity

Although the Halloween custom of trick-or-treating didn't become the universal holiday staple it is now until about World War II (with the earliest confirmed uses of the phrase "trick or treat" coming in the early 1950s), the practice of wearing disguises and going from house to house at that time of the year goes back centuries. As History explains, many people connect the modern practice of Halloween costumes back to the pre-Christian Celtic celebration of Samhain, a harvest festival ushering summer out and winter in. In some areas, celebrants of Samhain would dress themselves up in animal skins with the intent of driving away unwelcome spirits. By the Middle Ages, European people had developed the practice of mumming, wherein people in costume performed antics in exchange for food and drink.

By the ninth century, it was a common practice on November 2, All Souls' Day, for poor people to visit the homes of the rich to ask for a special pastry known as a soul cake in exchange for promises of prayers for the souls of the rich person's deceased relatives. This was known as "souling" and eventually became a custom for children. The most direct antecedent of trick-or-treating, though, would be the Scottish and Irish tradition of guising, in which costumed children would go door-to-door performing songs or tricks in exchange for coins or other small treats.

Divining your romantic future on Halloween

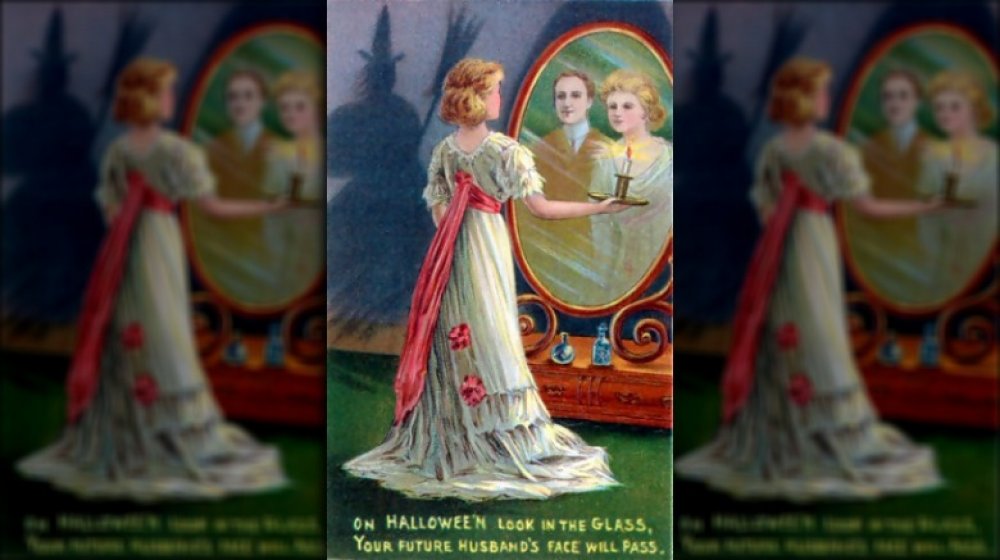

Before the world at large agreed that the best way to spend October 31 was by dressing up as Elsa from Frozen and walking through a suburb hoping for a full-sized Snickers bar, the traditional practice in Ireland, Scotland, and Wales was all about hooking up. (To be fair, for plenty of American adults in "sexy Spongebob" costumes or whatever, it's still about that.) Specifically, Halloween was the night in which the veil of magic was lifted enough that if played correctly, certain parlor games might reveal to you your future in love. Mental Floss collects a list of some of these incredible, strange games that were meant to tell you who you might marry, which include crawling under a blackberry bush, through which you might see the shadow of your lover in the moonlight.

Alternatively, once it's midnight, fill your mouth with salt and walk backwards down the stairs into your basement while holding a candle and a mirror. If you manage to make it to the bottom without tripping and setting your house on fire, you'll see the face of your future spouse in the reflection. Or you could throw a ball of yarn into a limekiln and wait for a fairy to tug on it and tell you the name of your beloved. Other games involved eggs, kale, snails, cornmeal, or tossing fruit into burning brandy, all of which are very sexy.

Halloween used to be in May

As most people know, the word "Halloween" is a shortening of the phrase "All Hallows' Eve," but unless you're Catholic or Eastern Orthodox, that might not mean much to you. All Hallows' Eve is the night before All Hallows' Day, also known as All Saints' Day. As the Encyclopedia Britannica explains, All Saints' Day is a commemoration of all the saints of the Church who have gone to Heaven, whether they are known or not. It's kind of a catchall in case the calendar of saints' days throughout the year misses someone. All Hallows' Eve is the first day of a three-day period known as Allhallowtide, which includes All Hallows' Eve on October 31, All Saints' Day on November 1, and All Souls' Day on November 2.

However, the feast of all the saints was not originally held in the autumn. The original day dedicated to all the martyrs of the Church was kept on May 13, which, as it happens, is the same date as the Roman festival of the dead known as Lemuria. As a number of Christian festivals were intentionally established on dates on or around popular pagan holidays, a day celebrating the dead in Christ on the same day that the Romans propitiated their dead may not be a coincidence. All Saints' Day was moved to November 1 in the eighth century by Pope Gregory III.

Bobbing for apples used to be sexier

Although it may not be as popular as it once was, one of the iconic party festivities at Halloween is bobbing for apples. Fall is a great time for apples and also apparently for lapping up 12 other kids' backwash as you try to grab a garbage red delicious with your nubby kid teeth. As History explains, however, bobbing for apples wasn't always about merely the fun of waterboarding yourself for the rare pleasure of a 50-cent fruit. It was, as many old-timey Halloween rituals were, all about heading to the bone zone.

One variation on the classic version of bobbing for apples involved each apple in the tub being assigned the name of a girl's potential suitor. The girl would then make her best attempt to grab the apple of the boy she liked. If she managed to grab it in one bite, they were destined for love. Getting it in two meant success but a love that would eventually fade. Anything more than that was bad news for love. Alternatively, participants would race to be the first to grab an apple with their teeth: Winning that race meant also winning the race for love. If a girl put the apple she successfully bobbed for under her pillow, she would see visions of her future spouse in her dreams.

The evolution of jack-o'-lanterns

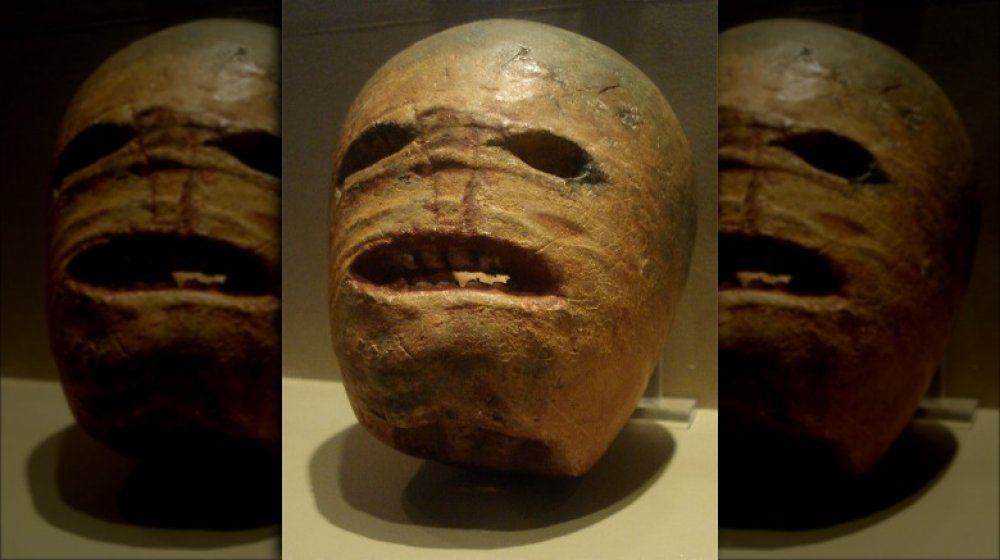

Probably the most iconic single image of Halloween is the jack-o'-lantern, the pumpkin carved with a grinning face lit by a candle perched within its hollowed-out interior. But this holiday icon wasn't always that way. As Merriam-Webster explains, the grinning pumpkin form of the jack-o'-lantern has only been around since the 19th century, but the term itself goes back at least another two centuries. The term originally applied to night watchmen who walked around at night with lanterns ("Jack" being a common word used to refer to a man whose name you didn't know). Soon, however, the term was applied to a different kind of light altogether: the spooky flame-like phosphorescent lights sometimes found in marshy areas that are also known as will-o'-the-wisps or ignis fatuus, among other names. This natural phenomenon was thought to be supernatural in nature.

The original Halloween lanterns, however, were (and in some places like the Isle of Man, still are) carved from turnips, potatoes, or other root vegetables, with their scary faces meant to frighten evil spirits. Once Irish and Scottish immigrants came to America, they found pumpkins both more abundant than turnips and also much easier to carve. An Irish legend also tells that the original "Jack of the lantern" was a man made to wander the Earth for Eternity after he found himself barred from both Heaven and Hell.

Trick-or-treat in a parking lot

Trick-or-treating was emphasized as a Halloween ritual in order to create a safe alternative to the dangerous pranks and vandalism often caused by roving bands of young troublemakers on October 31. But for some modern parents, trick-or-treating isn't safe enough, especially if you're the kind of parent who believes that Halloween is a pagan holiday celebrating Satan's birthday or whatever and that the crazies are putting razor blades in your M&Ms. As HuffPost explains, trunk or treat is the new hotness, created by church groups as a safer alternative to letting your kids talk to your neighbors.

Since the 1990s, the phenomenon of a bunch of cars parking in the church parking lot with kids going car-to-car asking for candy has exploded in popularity. For parents worried about safety, it lets them and their pastor keep a watchful eye over their little ones. For families in rural areas where houses might be miles apart, it's a sensible alternative. For parents who hate walking, it's a dream. As The New York Times points out, it's no longer strictly church groups who put together trunk-or-treat activities, and many Halloween enthusiasts relish the opportunity to spook up the trunks of their cars with festive decorations. This new Halloween practice will likely continue to grow, even though it is completely lame.

Naming Halloween

According to the Online Etymology Dictionary, in the late 13th century, All Saints' Day was being referred to as halwemesse day (in modern English, this would be "Hallowmas Day," similar to other holidays like Christmas and Michaelmas), and by the 1590s, we had Hallow-day. That same century attests to the night before being referred to as Allhallow-even. By the 17th century, the Scottish had shortened that to Hallow-e'en, and soon, the more popular form "Halloween" was being used. How did a regional Scottish abbreviation of a Christian holiday become universal? Poetry, of course.

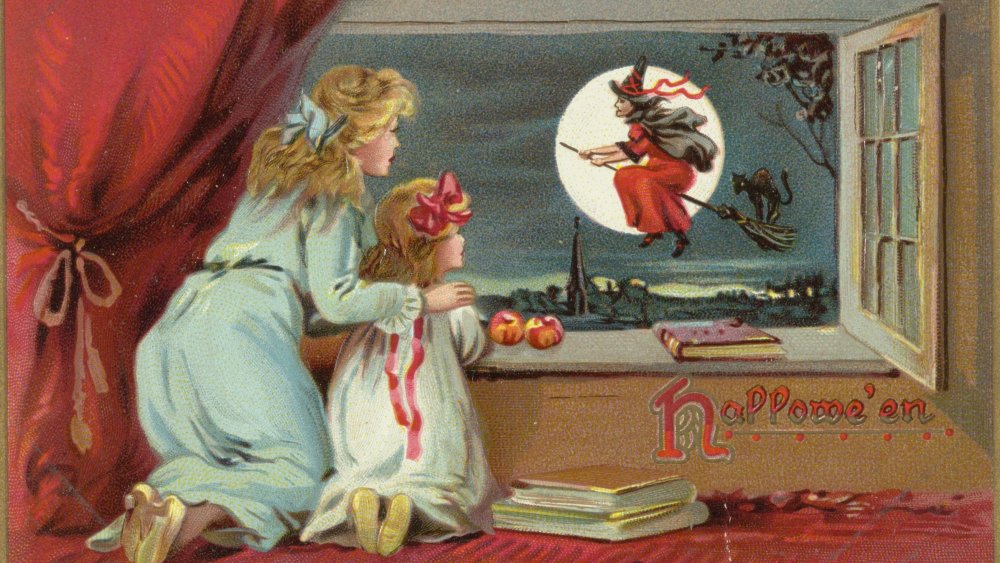

The specific word "Halloween" was popularized thanks to a poem of the same title by Scotland's greatest poet, Robert Burns, who is perhaps best known for his poem "To a Mouse," the origin of the phrase "the best laid plans of mice and men," or else for putting together the definitive version of the song everyone sings at New Year's. Burns' "Halloween" is a lengthy poem written in a mix of English and Scots that explains the rural celebration of Halloween as a night of harvest celebrations, mischief and pranks, divination rituals to determine one's future spouse, and, in Burns' own words, "a night when witches, devils, and other mischief-making beings are abroad on their baneful midnight errands." Burns' 1785 poem popularized not only the name "Halloween" but also much of the spooky lore around it.

The un-spookening of Halloween costumes

If it's true that the origins of dressing up for Halloween were people donning animal skins and terrifying masks to frighten away the unquiet dead who wander the Earth during that liminal space of time when summer ends and winter begins, it's pretty weird that we as a society have progressed to spending that night dressing up as Optimus Prime, a giant hot dog, a sexy cat or, worst of all, a visual pun. Business Insider tracked trends in Halloween costumes from the Civil War until today to see how we got to this point. From the 1870s until the 1890s, people primarily made their own crude costumes to appear as ghosts or witches, which seems completely in keeping with the original intent. However, even in that time, the Victorian trend of Orientalism meant that people would dress as "exotic" Chinese or Egyptian people.

The turn of the 20th century saw the beginning of the mass production of costumes, often made of paper, which codified colors like orange and black as the Halloween colors. Plastic costumes replaced paper ones in the 1940s, and the explosion in popularity of television in the 1950s is where things really started going off the rails, with kids dressing as their favorite TV stars, very few of whom were ghosts or witches. By the 1970s, you had blockbuster movies dictating trends, and there was just no going back.

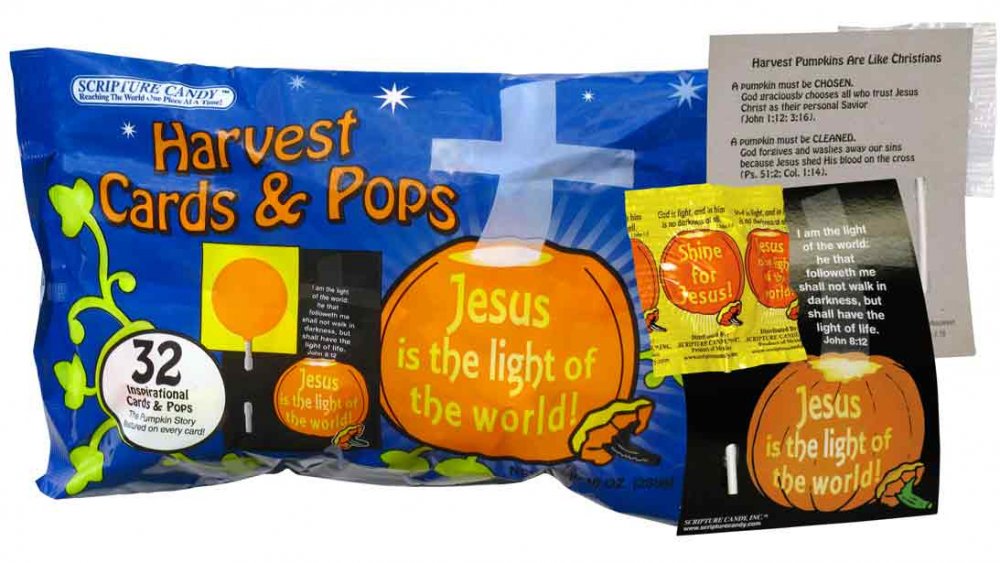

Keeping the hallow in Halloween

Halloween is, officially, a Christian holiday. It is a celebration dedicated to everyone who has ever achieved sanctification. Sure, yes, it has co-opted a number of pagan elements that generally dominate the Christianized rituals it's allegedly focused on, but that's also true of Christmas and Easter, the latter of which didn't even bother getting a Christian name. Nevertheless, that hasn't stopped a number of vocal Christian groups — primarily fundamentalist evangelicals — from claiming that Christians should not celebrate Halloween at all. According to Time, some conservative evangelicals call Halloween a time of "demonic spirits and curses," a trend which goes back as far as the 1960s, when evangelicals began accumulating more influence on the American political stage. By the 1970s, televangelists such as Jerry Falwell began warning against Halloween as a time of devil worship and sexual promiscuity.

As a result, since that time, and growing to extremes in the Satanic Panic of the 1980s, Christian groups have tried to offer alternatives to traditional Halloween activities. While this often means something along the lines of "fall festivals" held at churches or trunk or treat, it has also meant Christian versions of haunted houses, with names like "Scaremare" and "Hell House," which, rather than being filled with innocuous spooks, are narratives meant to show what Hell is like and how you will be tortured for doing drugs or kissing before marriage or whatever.