What It Was Like Taking Part In The Liberation Of WWII's Concentration Camps

They were called "concentration camps" because the people imprisoned there were "physically 'concentrated' in one location," The Jewish Virtual Library says. And the Nazis hit on the idea pretty early.

In 1933, they established their first 110 camps, and these early camps started out as holding centers for political opponents. It wasn't long before the list of those eligible for imprisonment rose. Most of the camps had specific purposes: there were forced labor camps, POW camps, extermination camps, and camps specifically used for housing — and euthanizing — the elderly.

The numbers are staggering. The US Holocaust Memorial Museum's list of concentration camps and ghettos established by the Nazis hit a shocking number: 42,500, via The New York Times. Of those, there were around 30,000 forced labor camps, 500 were brothels, and 1,150 were Jewish ghettos.

It's estimated that up to 20 million people died in the ghettos and camps. A small percentage survived to be liberated by Allied troops during World War II, and when liberation happened ... no one was prepared for what they found.

"I felt foolish, with all of that firepower"

Harry J. Herder, Jr., was a member of the Fifth Ranger Battalion, and according to the Minnesota Historical Society, he's written a memoir about his war experiences — including the liberation of Buchenwald.

It was April 11, 1945, when he wrote (via Remember) that he and the rest of his unit started by taking a run at the barbed wire fence. The tanks, he wrote, "slowed down, but they did not stop." Herder was on the top of the tank, armed to the teeth, and fully expecting to be attacked by the Germans occupying the camp. But there were no Germans.

"Slowly, as we formed up, a ragged group of human beings started to creep out of and from between the buildings in front of us. [...] They came out of the buildings and just stood there, making me feel foolish with all of that firepower hanging on me. I certainly wouldn't be needing it with these folks."

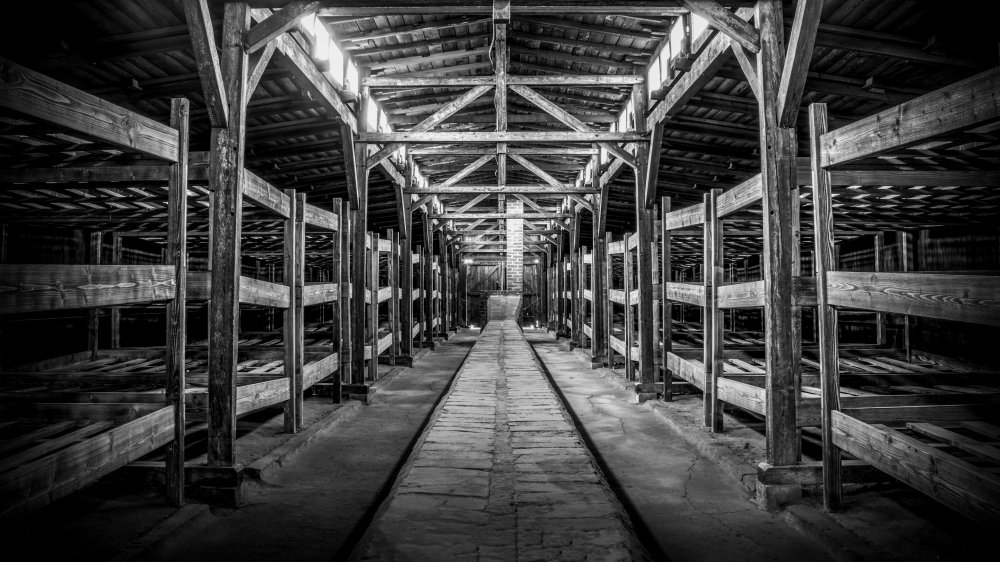

They were assigned there for four days and Herder wrote that they soon found those who had met them were just part of those who were left. "Just inside the door were people on the lower bunks so close to death they didn't have the strength to rise. They were, literally, skeletons covered with skin — nothing more than that — there appeared to be no substance to them."

One liberator discovers the horrors of a crematorium

The Fifth Ranger Battalion's Harry J. Herder, Jr. wrote (via Remember) that it was only when they started talking to some of the English-speaking prisoners that they learned where they were, and Herder's sergeant told them to look around, "to look as long as our stomachs lasted." So they did, walking through a gate and turning a corner: the sight before them made it clear what kind of place they were in.

"The bodies of human beings were stacked like cord wood. All of them dead. [...] The stack was about five feet high, maybe a little more; I could see over the top. They extended down the hill, only a slight hill, for fifty to seventy-five feet. Human bodies neatly stacked, naked, ready for disposal. The arms and legs were neatly arranged, but an occasional limb dangled oddly. [...] There was an aisle, then another stack, and another aisle, and more stacks. The Lord only knows how many there were."

It was then that another group of soldiers from their company pointed them toward another building. They went in, and he remembered the warmth, the small openings, the iron doors, and the trays that had been pulled out of some of those openings. One still held a skull, others held "partially disintegrated arms and legs." Then, Herder wrote, "I had enough. [...] Until then I had no idea what a crematorium was."

A Holocaust survivor imagines liberation

The British Library has preserved the story of Edith Birkin. Born in 1927, she was taken to Poland's Lodz ghetto in 1941, to Auschwitz in 1944, and sent on a death march to Flossenberg. It wasn't until 1945 that she was liberated from Belsen, and it didn't go as she expected.

"We were always imagining that when we were liberated, we are going to be dancing, and kissing them, [...] and we're going to embrace them, and ... Be happy, and dance, and God knows what, but all we wanted to do was to lie down and be allowed to be ill."

She went on to say that the liberation "was absolutely marvelous." They were given so much they had been deprived, and the most important? Water. She remembered her first meal — tinned creamed macaroni, which she continued to eat on the anniversary of liberation day.

Surviving was just the beginning. Birkin went to Prague, where she found a changed city. "I spent a few nights [...] roaming Prague you know, just feeling desperately lonely, because I suddenly realized there's nobody there."

Edith Birkin spent the following weeks in the city, looking for anyone she knew, hoping the friends and family she had been separated from would return. "Although we were free and liberated, it was the very worst time because we realized [...] nobody was going to come back. [...] I was seventeen."

Not all liberators made a good impression

Spanish political activist and columnist Jorges Semprún was a prisoner at Buchenwald, and he was there for the liberation. In his memoir (via The New York Times), he wrote that he had a less favorable impression of their liberators: "If their eyes were mirrors, it seems I'm not far from dead."

They had learned very quickly that the Nazi guards considered them something less than human, and saw the same expressions on the faces of the liberating army. That was echoed in other memoirs: Primo Levi remembered, "They did not greet us nor did they smile."

It was such a widely reported experience that historians have tried to figure out why so many liberators were remembered for the "confused restraint" they showed, and Robert Abzug of the University of Texas says there were a few things at work. For starters, GIs weren't told what they were going to find in the camps — words weren't going to capture the full horror of the scene anyway.

Many of the GIs who were helping with the liberation had been at war for years. They'd seen horrible things, but suddenly, they were confronted with this gruesome reality that nothing compared to. One doctor — Captain William J. Hagood, Jr. — summed it up this way: "All the grisly scenes I'd witnessed in four years of combat paled as I viewed the higgedly-piggedly stack of cadavers."

Regaining a sense of self after liberation

For many prisoners, something more than freedom came with liberation. That was a return of a sense of self, identity, and humanity, and for some, that came with something as simple as kindness.

Primo Levi was among those liberated from Auschwitz, and he wrote in his memoir (via The New York Times) of how a simple bath, given by a caring nurse, helped restore a sense of humanity. A simple bath, given by "tender hands [that] soaped, rubbed, massaged, and dried" was of the utmost importance, and provided a valuable counterpoint to the "grotesque-devilish-sacral bath [...] like the first one which had marked our descent into the concentration camp universe."

Many survivors would later remember how important it was to them just sharing a conversation with the soldiers. Many were terrified that no one would believe what they had been through, and talking to someone else who had seen it made them feel heard ... because they were.

Some soldiers went above and beyond to make these connections, doing the most unlikely of things in order to help the newly liberated restore their sense of being. Irving Lisman was an ambulance driver who arranged to have fabric and sewing supplies shipped to the Bad Gastein camp. Why? So they could make neckties, and give them out as an indication of respect. Captain Hagood asked his wife to send him lipstick: A reminder of the femininity so many women had lost in the camps.

"When next I looked, she was dead"

Liberation wasn't an entirely happy occasion, and it wasn't the end of the suffering of countless prisoners. The US Holocaust Memorial Museum estimates that in the few days after the liberation of Auschwitz, around half of those freed were dead from malnutrition. Soldiers who had just walked into camps worse than imagination could create didn't just save people, they watched those who they thought they'd saved continue to die.

In 2005, NPR shared the testimony of a British soldier named Tyler McKenney Payne. As Payne found when his men liberated the camp, there were not just adults, but babies, described as "shrunken wizened little things" by one eyewitness, via The London School of Economics and Political Science. Payne was on duty guarding the milk stores, and when mothers unable to nurse their babies came to him, he would pick babies out of the crowd to feed them. One stuck in his mind.

"And one woman who was — I think she was mad, kept kissing my feet and clothing, so I took the baby from her. When I looked at the baby, his face was black and he had been dead for a few days. I couldn't come to say it was dead, so I [...] poured milk down through its dead lips. The woman crooned and giggled with delight. I gave her the baby back and she staggered off and lay in the sun." When he saw her again, she was dead.

The skeletons of concentration camps

Ian Forsyth was 21 years old when he and the rest of the 15th/19th King's Royal Hussars arrived at Bergen-Belsen. They were among the first there, says The Guardian, and when they spoke with him in 2020, the now 96-year-old veteran remembered, "I couldn't believe what I was seeing — I couldn't believe... people could sink to that level [...] When you see a person who is a living skeleton, as these people were, it's difficult. It's astonishing that any human being could survive the terrible torture."

Susan Pollack — then Zsuzsanna Blau — was a teenager when she was at the liberation of Bergen-Belsen. She had been convinced that she was dying until someone picked her up off the ground. "I realized something that had changed — I was being treated with kindness."

She wasn't the only one plucked from among the dead and dying. Broadcaster Richard Dimbleby was there for the BBC, and it was dire stuff.

"I picked my way over corpse after corpse, until I heard one voice above the gentle moaning. I found a girl. She was a living skeleton. Impossible to gauge her age, for she had practically no hair left on her head, and her face was only a yellow parchment sheet, with two holes in it for eyes."

One camp survivor channeled trauma into film

Branko Lustig had a front-row spot at Auschwitz, for the hanging of seven prisoners. He later remembered what they'd said, via The Washington Post: "Remember how we died. Tell the story about us."

And he did — he was a producer on Steven Spielberg's Schindler's List, along with the TV series War and Remembrance. That 30-hour series was the first time crews had been allowed to film on the grounds of Auschwitz, and for Lustig, it was a return to the place where he had once been in charge of opening the main gate for officers as they arrived.

He had been moved to Bergen-Belsen by the time liberation came, just 12 years old, weighing 66 pounds, and fighting typhoid, according to the LA Times. He was so sick — and convinced that he was going to die — that when he heard the sounds, he was convinced he was listening to the trumpeting of angels. They weren't exactly angels — they were Scottish soldiers playing the bagpipes, per The Guardian.

Lustig and his mother were the only ones of his family to survive, and returning for the films was understandably difficult. But, it was important: "Maybe the reason I survived the camps was to help make movies about them, to show people what happened."

Liberation wasn't the end for many survivors

Traveling with the military units that headed up the liberation of camps across Europe was another group: the cameramen. Some were military and some were civilian newsmen, but according to the Imperial War Museums, the goal was always to document the horrors unfolding as the fences were torn down.

The film was a massive project, headed by Sidney Bernstein (who was then working for the Ministry of Information). He brought in Alfred Hitchcock to act as a consultant, and that's a good thing — there was a lot of film to go through. It poured in from Allied troops and 11 camps — hours of footage of the dead, the dying, the ovens, and the evidence of just how many were killed. "Nothing was wasted," reads the script. "Even the teeth were taken out of their mouth."

The documentary was never broadcast at the time. Exactly why is debated, but the footage was remastered and released in April 2017, to commemorate the 1945 liberation of Bergen-Belsen. Some of the survivors who appear in the film were tracked down by the director of a documentary about the film (via The Guardian), including Anita Lasker-Wallfisch. Then 89, she could reveal what happened after: "Every British soldier looked like a god to us." For many, liberation wasn't the end at all. "Some of those who were liberated remained in those camps for five years after liberation. Often, they had nowhere else to go," director and anthropologist André Singer said.

Broadcasting the liberation

On April 15, 1945, Richard Dimbleby became the first journalist to report on the liberation of Bergen-Belsen. His report was so graphic that it didn't air for days after he submitted it, for an eerie reason: The London School of Economics and Political Science says that no one back at the BBC believed what he was describing could possibly be real.

The report is chilling, filled with the sort of details that would make anyone listening wish they'd never heard it. Dimbleby tells of seeing four young people, sharing a bit of food while sitting just a few feet from a pile of decomposing corpses. He describes realizing that the people who met them outside were the fortunate ones, that "Inside the huts, it was even worse."

Dimbleby wrote that there were "poor starved creatures whose bodies [...] looked so utterly unreal and inhuman that I could have imagined that they had never lived at all. They were like polished skeletons [...]" Dimbleby knew that it wouldn't be enough just to tell people what happened. He had to make them believe it was real because the scale of the horrors they saw was simply so unbelievable.

"And with the dust was a smell"

Harry J. Herder of the Fifth Range Battalion later remembered the sight of the chimneys, the black smoke, and the smell. The smoke, he said (via Remember) was "blowing away from us, but we could still smell it. An ugly, horrible smell. A vicious smell."

As people started to wander out to meet them, they talked, but Herder said as he stood there, it was overwhelming. "It was then that the smell of the place started to get to me. [...] now there was a new odor, thick and hanging, and it assaulted the senses."

Richard Dimbleby described it for the BBC, too (via The London School of Economics and Political Science): "beyond the barrier was a whirling cloud of dust, [...] and with the dust was a smell, sickly and thick, the smell of death and decay of corruption and filth."

The liberation of Gunskirchen — a subcamp of Mauthausen — came as soldiers with the US Army accidentally stumbled across the camp. Time spoke with soldier Alan Moskin, who was 18 on that May day in 1945. He hadn't known anything about concentration camps at all and said that even as they walked through the forest, the first indication that something was wrong came wafting on the breeze. "We tried to cover our mouths and noses with a bandana, but it got worse and worse," Moskin said.

The memories of liberation are alive for WWII vets

Leila Levinson remembered her father always having a pea-green Army trunk with his name stenciled on it. A Nazi helmet always sat on top, but it wasn't until her father passed that she opened the trunk.

Inside was a shoebox of photos, including some dated to the landings at Normandy on D-Day. Others were labeled "Nordhausen, Germany. April 12, 1945." It was a subcamp of Buchenwald; Levinson had never known that her father had been stationed there to treat survivors, and when she asked family members about it, they simply said that he didn't speak of it.

According to the Warfare History Network, Levinson decided that she wanted to find other veterans who had been there and get their stories. She arranged 10 interviews with veterans and was "unprepared" for what she heard. One man named George Kaiser told her, "It was as if I had entered hell."

When Levinson left, she wrote, "When we shook hands goodbye, his eyes brimmed with sorrow. As we pulled away, I turned around and waved, and just before we turned the corner, Mr. Kaiser was still waving back. [...] I saw Mr. Kaiser's eyes seeing [...] more than he could bear. When he remembered, he was back in that moment, as if it was still happening. I learned [...] for every one of these veterans the moment of entering the camp, of walking through the gate is still happening."