The Great Fire Of London Finally Explained

Human history is filled with disaster and tragedy: sometimes it's personal, sometimes, it's on an epic scale. If there's one thing we can learn from these events, it's that the human race has an incredible ability to bounce back, even when it seems that all is lost.

And that had to seem like it was true in 1666, when fire swept through London and destroyed a massive part of the city. It was on the fourth day of the fire when Samuel Pepys wrote (via HistoryExtra) it was "the saddest sight of desolation that I ever saw; everywhere great fires, oyle-cellars, and brimstone, and other things burning."

Of all the things to face, fire has to be one of the most terrifying. Mindless, ever-hungry, destroying almost anything in its path before crawling on to devour more ... when the whole city's on fire, it's almost unimaginable. So let's talk about the Great Fire of London because the destruction of much of the medieval city is just part of the tragedy.

How did the Great Fire of London start?

Exactly how the Great Fire of London started, it's unclear. According to The Telegraph, though, we do know some of the important details. Thomas Farriner was the owner and operator of a bakehouse just off the aptly-named Pudding Lane. His workday ended at around 10 at night, and on September 1, 1666, things wrapped up as they usually did. He raked up the coals to control the fire in the hearth, and that was that.

At around midnight, Farriner's daughter, Hanna, headed down to light a candle. HistoryReader says they later claimed there wasn't enough of a fire left to even light that, but it was a little over an hour later that one of the family's servants — who had been sleeping downstairs — woke to a blaze: smoke filled the house, the main exit was blocked, and the heat was unbearable.

The family climbed out one of the upstairs windows and into a neighboring house — except for the maid. Too terrified to climb, she died in the blaze. Even sadder is that her name was never recorded, and this first casualty of the Great Fire of London has faded into anonymity.

The fire started to spread, up and down the lane. The city's Lord Mayor Thomas Bludworth was roused and headed to the scene, but delays — and a perfect storm of circumstances — meant that Pudding Lane was just the beginning.

How did the Great Fire of London spread so far and so fast?

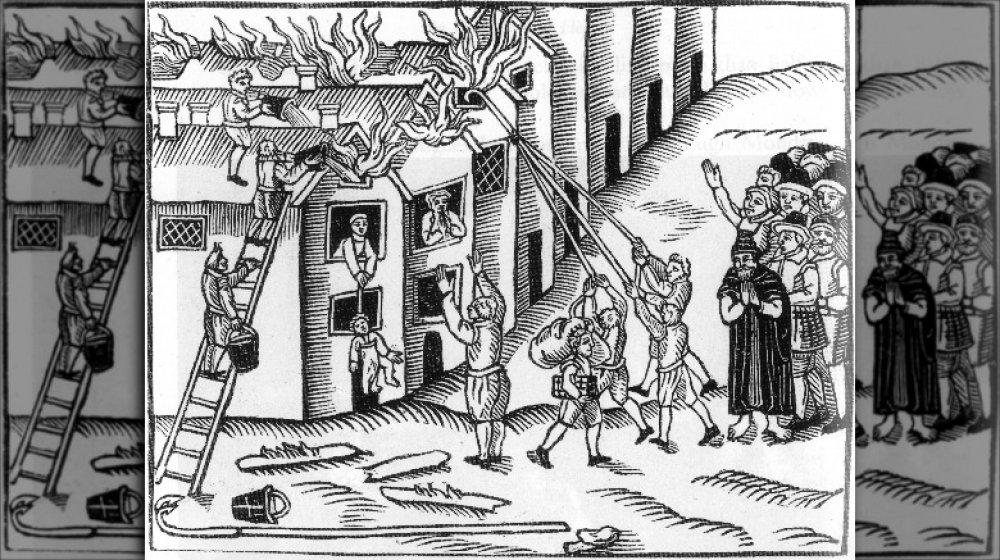

According to the London Fire Brigade, the medieval city had been built without much thought to fire safety, starting with the fact that homes reached out over the streets. It was easy for a fire to jump from one building to another, and while some of those buildings were thatched with pitch, there was a bigger problem.

That was the contents. Entire buildings were packed with hay and straw for the animals, not to mention kindling, coal, and firewood. Homes were dangerous fire hazards, with their own (via The Telegraph) fuel supplies.

The city was also incredibly dry. The summer of 1666 was a long one, and a severe drought meant that everything was more susceptible to the flames. Not only was water scarce, but London didn't have the fire-fighting equipment that would have been able to use it. Anyone trying to put out a fire had to rely on things like leather buckets, and one of the most popular ways to stop a fire was to tear down a building to create a firebreak. In this case, the Lord Mayor refused to give the order to do so, because he thought it wasn't serious.

It quickly became serious, when a strong wind picked up and blew embers across the city. When they hit the wharf — and the seemingly endless supplies of "tar, pitch, hemp, rosen, and flax" — all that was left to do was watch it burn.

An earlier fire helped stop the Great Fire

One of the reasons for the Lord Mayor's "Eh, whatever," attitude toward the fire was that it really wasn't anything new. Fires happened all the time. And it turns out that one of them may have helped stop the spread of the Great Fire of London.

In 1633, a fire broke out in the area around London Bridge. It started in the home of John Briggs, who presumably wasn't popular with his neighbors: It spread to and destroyed 43 houses.

While 33 years is a long time, it turns out things didn't move faster in ye olde days. By 1666, The Week says that some of those houses still hadn't been rebuilt, which ended up being a good thing. Most of those homes were at the northern end of London Bridge, and the open space that remained acted as a firebreak. It stopped the fire before it spread to the bridge — and beyond — so maybe Briggs's fire wasn't so bad, after all.

By the time the Great Fire of London was out, it had catastrophic effects

The Telegraph says that the worst day was September 4. That's when the military started destroying buildings and streets ahead of the fire, and it wasn't until the next day that the winds stopped, and so did the fire. Mostly — it smoldered for weeks, and as it did, people took stock of what had been lost.

It was a lot. It swept through 400 streets, per The Guardian, and destroyed 13,200 homes. To put that in perspective, consider this: New Geography says that the average size of your typical American village or township has a population of around 20,000. Also gone were 87 churches, and 44 livery halls ... along with everything else in an area that covered 373 acres. (A football field is 1.32 acres.)

The number of landmarks that were destroyed is staggering. There was Castle Baynard, where a few of Henry VIII's wives lived, and none of that remains. Then, there's Bridewell Palace, allegedly the last place Henry VIII saw Catherine of Aragon. There's an art deco building there now. The Great Conduit channeled water into the city and was completely destroyed, along with Old St. Paul's Cathedral.

And Whittington's Longhouse, which was later rebuilt, but not to scale. The three-time Lord Mayor Dick Whittington had spent a huge amount of his own money improving the city, and that included Whittington's Longhouse, a toilet that Londonist says had as many as 128 seats.

No one knows how many people died in the Great Fire

It's one of those "facts" that just gets repeated over and over: More people have died falling off the monument to the Great Fire of London than in the fire itself. Sounds unlikely, right? It is. The Smithsonian reported that in 2014, eight people had died falling from the monument, while the official death toll of the Great Fire was just six. That's true, but there's a huge problem with that number. No one was sifting through rubble looking for remains, and when it came to the poor and the lower-class citizens, well, no one really cared enough to look for them, much less count how many had died.

The actual death toll is estimated to be in the hundreds, if not thousands, which makes more sense. So, who were the six? The first was Thomas Farriner's nameless maid.

There was also the elderly Paul Lowell, a watchmaker who lived on Shoe Lane, and whose remains were found in his home. Richard Yrde's body was found in St. Mary Woolnoth, and he died of smoke inhalation. Another anonymous victim — this time, an old woman — was found outside St. Paul's, where she had been consumed by flames. The others were nameless people found inside St. Paul's.

Then, Londonist says there were indirect deaths, like James Shirley and his wife. They found themselves homeless and died in the cold winter weather that came to the refugee camp they were forced to shelter in.

There were a lot of conspiracy theories about how the Great Fire started

The fire, says The Telegraph, was still smoldering when the conspiracy theories started swirling. Among the first to be blamed were the Dutch, and even the staunchest skeptic has to admit the timing was pretty suspicious. Just two weeks before the Great Fire of London, English troops had burned the Dutch port town of West-Terschelling, so it was understandable that people might think they wanted payback.

The search for a scapegoat got so bad that the Catholic Herald says King Charles II actually had to make an official decree that said essentially, "less fighting each other, more fighting the fire, please and thank you," but still, Londonist reports that at least one woman was killed by a mob in Moorfields who was convinced she was guilty of arson.

The French were also blamed, and so were the Catholics. On September 25, the government organized a committee to hear thoughts and theories from the public, and that went about as well as could be expected. The Jesuits were blamed, too (by those convinced that they were experts at fireworks), and the conspiracy theories just didn't go away. Plaques promoting the idea that the fire was a Papist plot were up and on display into the 18th century, even though the government declared there was no evidence of a conspiracy whatsoever.

The Great Fire of London through the eyes of Samuel Pepys

Samuel Pepys had a storied career in the British government and military, but according to the BBC, his most important contribution came to those after his time. Between 1660 and 1669, he wrote a diary that gave a firsthand account of some of the decade's most important events, ranging from the plague to the coronation of Charles II. He also wrote about the Great Fire of London.

Royal Museums Greenwich reports that while he first shrugged off the seriousness of the blaze, spending that first night "mighty merry," he was also among those who went to the King and appealed for drastic actions to be taken. That concern was largely ignored, and he returned to take care of his own family and possessions ... including his Parmesan cheese.

Pepys's diaries give us an incredibly personal glimpse into the fire. That includes the lengths to which some people tried desperately to save their most prized possessions: Pepys wrote that on September 4, he dug a pit in his garden, where he buried "my Parmazan cheese, as well as my wine and some other things." Priorities!

Others weren't so fortunate, and he wrote of seeing people hurling their possessions into the street or the river in a desperate attempt to save them, and of seeing the pigeons, burning their wings as they flew over the fire, and falling. It's heartbreaking stuff.

A watchmaker was executed for starting the Great Fire of London

If there's one thing that hasn't changed, it's the fact that people like to have someone to blame. The Great Fire of London was so catastrophic, it's easy to see why no one seemed to want to accept the fact that it was an accident. So, they made someone pay.

His name was Robert Hubert, and he was a French watchmaker. Originally from Rouen, Executed Today says that he was arrested trying to leave Essex with a group of other people. Hubert insisted he had set the fire, saying — in front of a jury — that he'd been the one to "put a fireball" through the window of the bakery, but there were a lot of things that just didn't add up.

That starts with the testimony of Thomas Farriner, who started by saying there hadn't been a window where Hubert claimed there was. His confession was "so disjointed" that the Chief Justice and the jury didn't even think he was guilty, but he kept insisting, so they found him guilty and hanged him.

Later, proof came out that he definitely didn't do it: Hubert didn't even arrive in London until several days after the fire started. Why confess? Lord Clarendon would speculate that he was simply "a poor distracted wretch weary of his life, and chose to part with it this way."

It wasn't the first or the last major fire

We might think of the Great Fire of London as the one that really helped plant the roots of today's London, but there's actually a shocking number of fires in the city's history — and according to Mental Floss, they go all the way back to the year 60.

That's when Boudicea burned what was then Londinium to the ground, angry because lands that should have gone to her after the death of her husband were claimed by the Romans. She did such a good job of it that there's a layer of red-brown ash in the ground, marking the "before" and "after."

Just 62 years later, the city was destroyed again. It was called the Hadrianic Fire, and then, between 675 and 1087, there were nine major fires and St. Paul's Cathedral was burned three times — with maybe a fourth destruction coming in 1135, but no one's certain on whether or not the cathedral survived that one. Then, there's 1212, 1633, 1794, and The New York Times says that catastrophic fires continued into the modern era. Hyde Park's magnificent Crystal Palace burned in 1936, the blitz of 1940 caused widespread destruction, and in ye olden times, when smoking was common in the underground — ie., 1987 — King's Cross station burned.

Fire was responsible for what the BBC called "one of the UK's worst modern disasters," too — the 2017 tragedy of Grenfell Tower.

The London that could have been

Christopher Wren is buried in St. Pauls' Cathedral, and translating his epitaph from Latin gets you a sentiment that's something like, "You want to see a memorial? Look around."

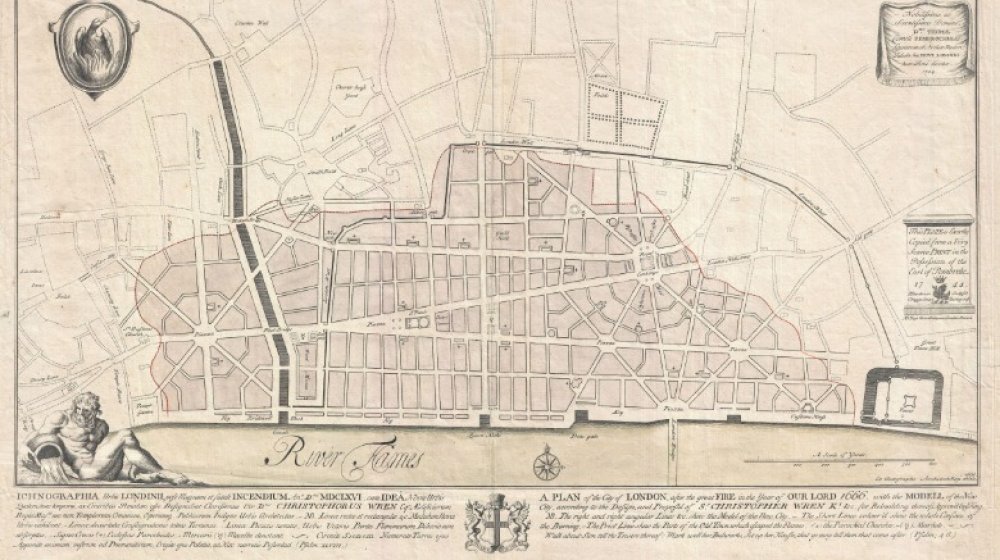

And that's legit. ThoughtCo. says that Wren designed St. Paul's along with 51 other churches, and was appointed to oversee all of the building projects. Still, one of Wren's largest suggestions wasn't used. His idea (pictured), would have given London wide streets that branched out from a centralized hub. That's a huge difference from the London we all know and love, which is charming, but looks like someone threw some spaghetti on the ground and said, "Yep, that's the plan!"

Wren wasn't the only one that had a different vision for the city after the fire. Richard Newcourt proposed a grid plan, centered around public squares that each had a church in the center. London didn't want it, but the BBC says his grid design was used in Philadelphia — and went on to become the basis for many American cities.

The epically-named Valentine Knight suggested a similar grid system with a new toll canal (and was arrested for suggesting the king would personally benefit from it). Robert Hooke is credited with another grid pattern, and John Evelyn wanted to rebuild London in the style of Rome, with wide avenues and piazzas.

None of those plans came to fruition, though, for two big reasons: money, and the fact that no one wanted to give up land.

The secret hidden in the Great Fire of London's memorial monument

The monument to the Great Fire of London is pretty neat: it's in the shape of a torch, and it sits 61 meters away from where Thomas Farriner's bakery once stood. It's also 61 meters tall, meaning that if you were to tip it over, the flame of the torch would touch the spot where the fire started. Clever, right?

Most people who visit it climb the 311 steps to the top, presumably rest for a bit, and then go back down. But according to The Telegraph, there's a secret: a hidden laboratory, beneath the monument.

It's accessed through a trap door in the ticket office, and it was installed by the monument's architects: Christopher Wren and Robert Hooke. Hooke was the first one to realize fossils were the remains of creatures and coined the word "cell." He was also an astronomer.

Hooke and Wren were trying to prove without a doubt that we were revolving around the sun and that Earth wasn't the center of the universe. They needed a big telescope to do it, and basically realized that they were building this massive tower anyway, why not make it a telescope?

Unfortunately, the plans never came to fruition. Vibrations from the streets outside meant that keeping the lenses of the telescope aligned and making accurate measurements was pretty much impossible, and the theory wouldn't be proven for another 150 years.

There are 18 pre-fire buildings you can still see today

While a building dating to the 18th century might be considered old by American standards, that's nothing compared to the "old" of London. Historic UK took a look at how many buildings that survived the Great Fire of London can still be seen today, and they found that there's 18 left. That's impressive, especially considering how much of London was destroyed in later disasters, like the Blitz of World War II.

There are a couple of pubs remaining: The Olde Wine Shades (built in 1663), The Seven Stars (1602), and The Hoop and Grapes (late 1500s). There are a few churches, like St. Andrew Undershaft, which was built in 1532, survived both the Great Fire and the Blitz, and had its medieval stained glass windows destroyed by an IRA attack in 1992. St. Helen's Bishopgate still stands, too — it was built in the 12th century and was Shakespeare's local parish.

The Old Curiosity Shop (pictured) still stands; built in 1567, it was a subject of Charles Dickens. The Guildhall was built in 1411 (and is now home to a Roman-era amphitheater), and the oldest house in the city still stands, too. It's 41 Cloth Fair, and it was built between 1597 and 1614. That's old!