Things Lovecraft Country Gets Right About History

Created and written by Misha Green, the 2020 HBO show Lovecraft Country presents a science-fiction world that is as supernatural as it is racist. Using the book Lovecraft Country by Matt Ruff as a template, the show creates a fantastical world of monsters and spells grounded in historical horrors.

Seeking to recreate the world envisioned by H.P. Lovecraft, who was notoriously racist, Lovecraft Country shines a light on the racist past of the United States, incorporating the horrors of racism into the foundation of the story the way Lovecraft had incorporated his racism as the foundation for his stories.

Lovecraft Country doesn't hesitate at dropping historical references, and the following list is hardly complete. But with every new episode, audiences are exposed to a plethora of allusions. And while some stories may be well-known, others may be new. These are some of the things Lovecraft Country gets right about history.

Driving over oppression

The first line of Lovecraft Country that occurs in reality, "Just going over another bridge named after some dead slave owner," is a sharp reminder as to how many bridges, schools, and hospitals are named after people who enslaved other people. Directed by Yann Demange and written by Misha Green, "Sundown" is immediate in its unapologetic addressing of horror that isn't limited to the fantastical.

According to The Geekiary, the bridge driven over on the Kentucky-Illinois border on the show may itself be fictional, but there are countless bridges in Kentucky alone named after slave owners. Another example of such a bridge is the Edmund Pettus Bridge, in Selma, Alabama, a key figure in Bloody Sunday during the Selma-to-Montgomery marches. The bridge itself is named after Edmund Winston Pettus, who was not only an enthusiastic supporter of enslavement but later a leader in the Alabama Ku Klux Klan as well. According to Lovecraft Country: An Unofficial Syllabus, Roebling Bridge is another example, a bridge connecting Kentucky and Ohio that was only built with the arrangement that Kentucky was "reimbursed for every enslaved person who used the bridge to escape to freedom."

According to Refinery29, bridges aren't the only pieces of public infrastructure named after people who enslaved other people. High schools, universities, and highways all across the United States and the United Kingdom bear the names of such slave owners.

Uncle George's travel guide

Uncle George's guidebook that he's leaving to research in "Sundown" is based on a very real and very necessary part of Black Americans' lives before the Civil Rights Era. Up until the 1970s, a number of travel guides existed that were written by and for Black people who wanted to travel and vacation around the United States without fear of harassment or violence.

According to The Atlantic, the most famous of these was The Negro Motorist Green Book by Victor H. Green, which had the widest readership and was published for the longest amount for time, from 1936 to 1966. By the early 1960s, the Green Book had a circulation of almost two million people. But there were many other Black travelers' guides, such as Hackley and Harrison's Hotel and Apartment Guide for Colored Travelers, published from 1930 to 1931, and Grayson's Guide: The Go Guide to Pleasant Motoring, published from 1953 to 1959.

Not only was there the fear of being shut out of public spaces as well as entire towns, such as Edmond, Oklahoma — which proudly proclaimed on its postcards, "'A Good Place to Live.' 6,000 Live Citizens. No Negroes" — but there was also the very real fear of lynching. Against this, Black travelers' guides sought to help Black people have the freedom to travel.

Sundown towns

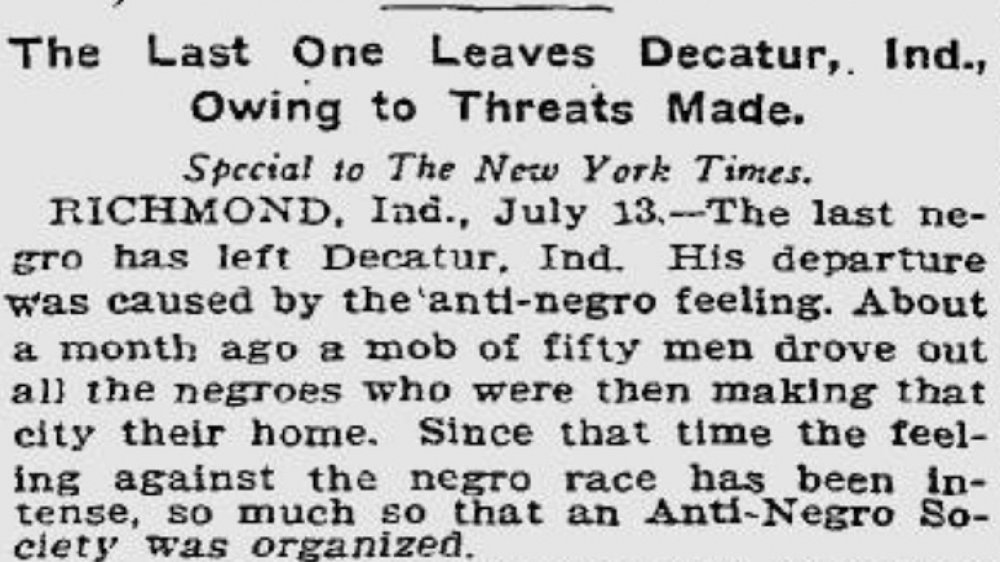

Places like Edmond, Oklahoma, were known as "sundown towns." Sundown towns were communities that actively kept non-white people from residing there. The practice began around 1890 and lasted until 1968. Thousands of towns drove out the Black people living there, passed laws prohibiting Black people from entering town limits after dark, or kept them from owning or renting property at all. Uncle George, Atticus, and Leti have the misfortune of finding themselves in one at one point during "Sundown."

These rules were enforced through policy as well as violence. White people often murdered Black people who they perceived to be violating their horrific customs. According to Sundown Towns by James Loewen, many towns also displayed signs warning Black people not to "let the sun go down on you in [town's name]." Sundown towns also weren't used exclusively against Black people and were often set up to oppress Native people, Chinese, and Mexicans as well.

Most sundown towns were established in the north and west during the Great Migration, in an attempt by white people to keep Black people from moving into their towns while simultaneously using it as an excuse to drive out the Black people already residing there. As of 2005, some towns and suburbs could still be considered sundown towns.

Anna, Illinois

One such sundown town is Anna, Illinois, mentioned by Uncle George in "Sundown" while he's icing his knees, grateful that they even work at all after being broken by a white mob outside of Anna. A real town in Illinois, Anna's name is an acronym for "Ain't No N***ers Allowed."

According to Sundown Towns by James Loewen, Anna became a sundown town in 1909, after a white woman coincidentally named Anna Pelley was found dead with her clothing ripped off in Cairo, 30 miles south of Anna. Using bloodhounds, the police arrested a Black man named Will James, but they weren't sure if they even had the right assailant. Unfortunately, the mob cared little about actual evidence, and after overpowering the prison guides, they lynched James. Women were primarily responsible for hanging James, while the men riddled him with bullets and dragged his body through the city after the rope broke. Many sundown towns have such a story to justify their behavior and status as a sundown town.

After the 1909 lynching, every Black family was driven out of Anna, except for the Sales family, according to ProPublica. John and Emily Sales lived in Anna for 50 years, and when John died in 1916, his obituary described him as "the only colored man who has ever lived in this city." For some reason, some sundown towns occasionally would have one Black family despite being explicitly a sundown town. To this day, Anna's population is overwhelmingly white.

H.P. Lovecraft's racism

In "Sundown," Atticus picks up a book of short stories by H.P. Lovecraft and recalls how his father made him memorize Lovecraft's poem "On the Creation of N***ers." Written in 1912 when Lovecraft was in his early twenties, the eight-line poem seeks to describe how Black people were created as an afterthought.

According to Literary Hub, Lovecraft made no attempt to conceal his bigotry and white supremacist thinking, which became the basis for his horror fiction. But his xenophobia and racism have often been excused or treated with disregard. The World Fantasy Award, awarded for fantastical fiction, was once a bust of Lovecraft himself. Nnedi Okorafor, after becoming the first Black person to win the WFA for Best Novel, noted the juxtaposition: "A statuette of this racist man's head is one of my greatest honors as a writer."

Despite Lovecraft's defenders arguing to keep the prize as it was, as of 2016, the award was remodeled.

Prince Hall the freemason

During the uncomfortable dinner that Atticus and Uncle George are forced to attend at Samuel's mansion in "Sundown," Uncle George delightfully launches into a little history lesson about Prince Hall. Uncle George reveals that his knowledge of secret societies comes from the fact that he's a member of the Prince Hall Freemasons, a branch of Freemasonry in the United States that was founded because Prince Hall was refused membership into the existing all-white masonic lodges.

Because there were several people named Prince Hall in Boston at the time, it's difficult to determine his time and place of birth or information about his early childhood. But according to the Prince Hall Affiliation, in early 1775, Hall and 14 other free Black men tried to join the St. John's Lodge of Free and Accepted Masons in Boston. However, they were rejected because of their race. Later that year, they sought admission through the Grand Lodge of Ireland and were admitted to Lodge No. 441. But when they tried to apply for charters to create their own lodge, they were repeatedly rejected.

After applying to the Grand Lodge of England, they received a charter and were able to create African Lodge No. 1, which was later renamed African Lodge No. 459, the first Black masonic lodge in the United States. However, the Grand Lodge of England didn't grant them full stature until 1784.

Black-owned boarding houses

Ruby first mentions staying in a boarding house in "Sundown," but in the third episode, "Holy Ghost," directed by Daniel Sackheim and written by Misha Green, the audience sees Leti try to establish one of her own. Black-owned and Black-friendly boarding houses were key elements of survival during segregation, offering not only a place to live and food but providing a space for artistic collaboration, political activity, and safety.

According to Wear Your Voice, one of the most famous Black-owned boarding houses was deemed "N***erati Manor" by writer Zora Neale Hurston (pictured above). Owned by Black New Yorker Iolanthe Sydney, the boarding house was a rent-free space that was intended to provide housing to Black artists. And Hurston wasn't the only artist to pass through the doors. Countee Cullen, Dorothy West, and Langston Hughes were also prominent features.

It was in N***erati Manor that the literary journal Fire was produced. According to Langston Hughes, "we set out to publish Fire, a Negro quarterly of the arts èpater le bourgeois, to burn up a lot of the old stereotyped Uncle Tom ideas of the past." Unfortunately, Fire's first issue was also its last.

Unable to live in peace

Unfortunately, the response that Leti received in "Holy Ghost" when she opened her boarding house in a white neighborhood is more than historically accurate. All around the United States, many Black residents were harassed in their homes with threatening phone calls, windows being broken, burning crosses put outside, and even bombings by white people hoping to drive Black people out of the neighborhood. This phenomenon is well-documented throughout the 1900s. According to "Crimes without Punishment: White Neighbors' Resistance to Black Entry" by Leonard S. Rubinowitz, "Resistance against African Americans moving into white districts occurred more commonly as thousands of small acts of terrorism."

According to National Geographic, 1917 through 1923 is especially known as a period when mobs of white people attacked and massacred Black people across the country. Lovecraft Country takes place in 1955, but these sorts of attacks continued and increased, especially in Chicago, after World War II. One such incident occurred in the suburb of Cicero in 1951, when 29-year-old Black war veteran Harvey E. Clark, Jr. tried to move his family into a $60 apartment. A mob of 4,000 white people showed up and rioted over the next few days, throwing torches and bricks into the apartment building while the police simply watched.

A physician's horror show

The neighbors outside aren't the only horrifying thing about Leti's new house. Inside lurks a more fantastical horror: the ghost of Hiram Epstein, a doctor who performed experiments on Black people. Even though Hiram Epstein himself isn't real, he has a horrific precedent. And according to Lovecraft Country: An Unofficial Syllabus, three of the names called out by Leti when she attempts to banish the ghost are the names of real victims from a real-life horror story.

One version of Epstein was J. Marion Sims, also known as the "Father of Gynecology," a title he acquired based on incredibly unethical research. When Leti calls out the names "Anarcha, Lucy, and Betsey," the show pays homage to the women who gave their lives to be the "Mothers of Modern Gynecology." All three women, enslaved women who suffered from fistulas, endured dozens of surgeries by Sims without their consent and without the use of anesthesia, because of the belief that Black people don't feel pain. Sims himself observed that "Lucy's agony was extreme."

Other medical doctors like Dr. Thomas Hamilton also conducted various experiments, such as those on John Brown, an enslaved man who later escaped from slavery and moved to London. Hamilton performed experiments such as draining Brown's blood or determining how deep Brown's dark skin went: "This he did by applying blisters to my hands, legs and feet, which bear the scars to this day."

That newcomer preacher

During Leti's housewarming party in "Holy Ghost", one of the guests makes a sly reference to Martin Luther King Jr. As Leti walks by, one of the guests is saying, "You heard about that newcomer preacher that's supposed to jumpstart the movement, right? Michael, right? He's going by Martin now." This is actually a direct reference to Martin Luther King Sr.'s changing of his and his son's names.

According to Time, King Sr., a pastor from Georgia then going by Michael King Sr., was inspired during his travels to Germany by the Protestant reformer Martin Luther. He decided to honor Martin Luther by not only changing his own name but also his son's name not long after he changed his own. Although, this happened when King Jr. was five years old rather than during his work in the Civil Rights Movement.

One of the guests also mentions that they heard "he was engaged to a white woman," to which the first guest responds, "Nah. They made him marry a colored one last year." Overhearing this conversation, Leti remarks, "Loving a white woman doesn't mean he can't stand up for colored folks. I guess." According to Politico Magazine, this back-and-forth is actually based on the true story of Betty Moitz, a young white woman with whom King Jr. had a brief, but serious, relationship. Many of King's friends sought to discourage their relationship, "knowing what an interracial relationship would mean for his future."

The Devil in the details

In the fifth episode "Strange Case," directed by Cheryl Dunye and written by Misha Green, Sonya Winton-Odamtten, and Jonathan I. Kidd, Ruby is given the ability to transform into a white woman named "Hilary." But the difference in treatment that Hilary receives compared to Ruby is not the only historically accurate thing about Hilary's appearance.

According to Lovecraft Country: An Unofficial Syllabus, the newspaper that Hilary reads is full of historically accurate representations of the media at the time. One of the headlines that can be seen reads "Ike Fared Badly, Study of Congress Actions Shows," referring to Chicago's Eisenhower Expressway. In building the Eisenhower Expressway, hundreds of business and residential buildings were destroyed. Although thousands of housing units would be destroyed, no alternatives were provided for the people and families who were displaced.

Hilary's newspaper also features timely advertisements for skin-lightening products. Such products were common throughout the 20th century, with advertisements such as those by J. Strickland & Co., a company founded by a white man, literally picturing a dark-skinned woman turning white.

Bessie Stringfield riding in style

When Hippolyte is going through her transformations in the seventh episode "I Am," directed by Charlotte Sieling and written by Misha Green and Shannon Houston, she drives by a Black woman on a motorcycle. This woman is none other than Bessie B. Stringfield, the first Black woman to ride a motorcycle by herself across the United States.

According to BlackPast, Stringfield started riding when she was 16 years old, and she'd soon mastered the art. She made her first solo trek across all 48 states in 1930, and over the next two decades, she'd make seven more long-distance solo rides. During her travels, white people often denied her accommodations because of her skin color, and as a result, Stringfield often slept at gas stations on her motorcycle.

According to The Heroine Collective, after working as a civilian motorcycle dispatch rider for the US Army during World War II, Stringfield moved to Miami, where she worked as a nurse. In addition to working as a licensed nurse, Stringfield founded the Iron Horse Motorcycle Club. Once, she even reportedly won a local flat track race disguised as a man, but she was denied the prize money when she took off her helmet.

Undeterred, Stringfield rode motorcycles up until her death at the age of 82 in 1993.

The horror of saying goodbye

In "Jig-a-Bobo," the eighth episode of Lovecraft Country, directed by Misha Green and written by both Misha Green and Ihuoma Ofordire, the foredoomed fate of Diana's friend Bobo comes to fruition. "Bobo" was the real-life nickname for Emmett Till, and the show makes multiple references to Till in "Holy Ghost," with Bobo's outfit as well as the answer he receives from the Ouija board.

According to Fansided, the line of people standing in line for Till's wake is an accurate depiction of the thousands of people who came to view Till's body. An estimated 50,000 people saw the body on Friday, September 2, 1955, and another 10,000 saw it the following day.

The casket was displayed until it was buried the following Tuesday. Till's mother, Mamie Till Mobley, had insisted on having an open-casket at his funeral, later saying, "I wanted the world to see what they did to my baby."