The Messed Up History Of Old-Timey Child Labor

The phrase "child labor" can bring up some very specific images and feelings: neglect, abuse, injustice ... the list of terrible things associated with child labor is a long one. Just look at the outrage that happened not only when the world's chocolate companies — like Nestle — were discovered to be using child labor in their chocolate supply chain, but when it was found that they kept doing it, even after promising otherwise.

Child labor is everywhere: it's even a huge problem in the industry that produces your favorite healthy snack, the cashew. Is nothing sacred? Certainly not childhood, it turns out.

While child labor definitely isn't anything new, here's the weird thing: It wasn't always viewed as horrible. Weird and almost unthinkable, right? So let's talk about the weird, messed up history of child labor, and remember a time when kids had worries other than incomprehensible algebra homework, or what version of smartphone they were going to get for Christmas.

Child labor wasn't always seen as bad

Child labor might be a dirty term in the 21st century, but that wasn't always the case. Long before the practice of turning children into a workforce reached its height during the Industrial Revolution, children were pretty much always expected to earn their keep.

According to Mount Holyoke College, rural families were a perfect example of this. Children didn't just go to school, then come home to watch their version of 18th and 19th-century television. (Clouds? Paint drying? We're not sure, but it was probably still more entertaining than today's TV.) Boys were expected to work in the fields and tend to animals like cattle and horses, while girls were put to work milking cows, collecting eggs, caring for the family's poultry, and doing the household chores. If the family owned a business, children were expected to help out there, too.

It wasn't just a source of cheap (ie., free) labor, it was practical. Children were going to inherit the farm — or marry into living on another — or they were going to inherit the business. Kids become adults eventually, and they'd have to know how to do things like plow a field or cook a meal. And if, say, Dad was a cobbler and Junior was going to take over the business, then by gosh, he'd better learn how to repair some shoes.

The Industrial Revolution and the rise of child labor

It wasn't until the Industrial Revolution that child labor became synonymous with abuse and cruelty, and there were a weird series of circumstances that came together to create the perfect storm. According to Owlcation, it came from an attempt to make Europe "more humanitarian."

When Englishman Jonah Hanway went to China and saw horrible human rights abuses, he decided he wanted to know what was going on in England's own workhouses. What he found was barely better, and he decided to push for legislation that got children out of workhouses and into homes ASAP. In 1773, an act of Parliament restricted children's stay in workhouses to just three weeks, and that meant they needed to go somewhere.

The answer was to board them out to tradesmen and business owners. In theory, it's not a terrible idea. Children would — again, in theory — have a home, food, authority figures, and training in a job or trade to prepare them for adulthood. What could go wrong?

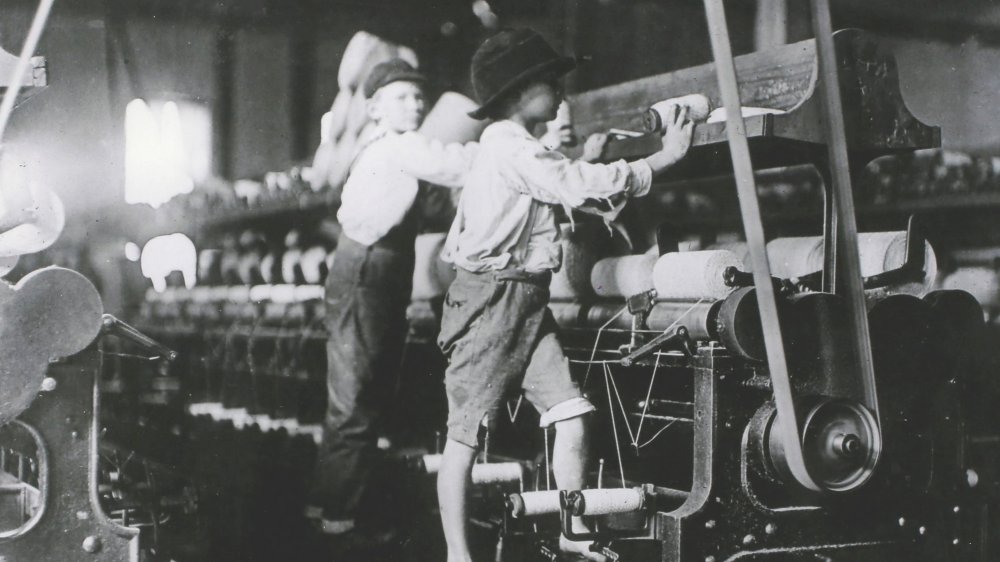

A lot, it turns out. Those adults realized a few crucial things: children were unlikely to protest long hours or the kind of treatment adult workers might think unfair or cruel. They could be paid less or nothing at all, they weren't going to be organizing or joining unions, there would be no health and safety complaints, and their tiny bodies were perfect for fitting into enclosed, dangerous spaces adults couldn't go (via History).

The life of coal mining children was miserable

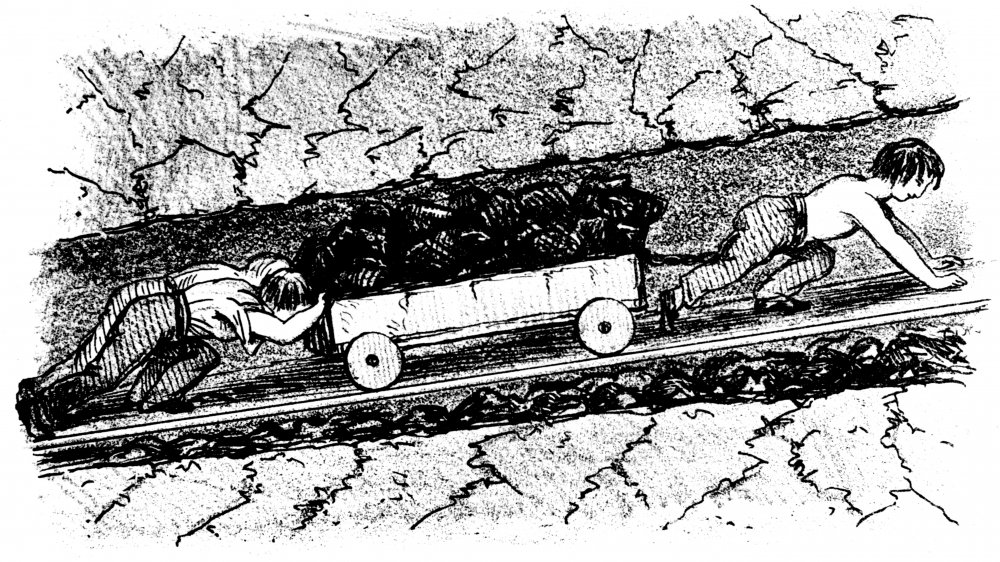

Coal mining started in 1575, the British Newspaper Archive says, but it wasn't until the Industrial Revolution that it became a massive industry that needed tons of workers. By the early 19th century, Britain's mines were filled with children as well as adults.

Among their jobs, per National Museum Wales, were tasks like operating the doors that allowed ventilation through the occupied mine shafts, driving the pit ponies who pulled mine carts through larger roadways, and helping cut the coal itself.

Perhaps most shocking were the children sent into the narrowest of shafts, then fitted with a girdle and belt and tasked with hauling huge amounts of coal. This account ran in one paper: "When I put on the girdle the blisters would break and the girdle would stick, [...] the skin was broken, and the blood ran down. [...] If we said anything, they [...] would take a sticks and beat us!"

Spartacus says that for many, days started at 2 am, ended at 8 pm, and it wasn't just cruel overseers here. Jane Watson was interviewed at the age of 40 and spoke of the back-breaking work in the mines she did. She described it as "horse work," and lamented "Women so soon get weak that they are forced to take the little ones down to relieve them; even children of six years of age do much to relieve the burthen."

Newsboys had a miserable life of child labor

They're featured for background and atmosphere in so many movies. You can easily picture chirpy newsboys sitting on a stack of newspapers, shouting things like "Extra, extra, read all about it!" The reality was quite different.

Take this description from Charles Loring Brace, a reformer working in the mid-1800s (via Digital History): "I remember one cold night seeing some 10 or a dozen of the little homeless creatures piled together to keep each other warm beneath the stairway of The [New York] Sun office. There used to be a mass of them also at The Atlas office, sleeping in the lobbies, until the printers drove them away by pouring water on them."

Just a few years later, James B. McCabe, Jr. estimated there were around 10,000 homeless children on the New York City streets, and "newsboys constitute an important division of this army."

The New York Times says they led a dire existence: newsboys bought their papers upfront, and there were no returns. That means a cutthroat market, with countless boys hawking the papers of as many as 50 different dailies in New York City alone. And getting out of that life was difficult, as many boys as young as 6 opted to spend their money at saloons, where the saloonkeepers would sell them whiskey for cheap. By 1899, newsboys had organized enough to launch a massive strike that drew some attention to their miserable lots in life and to the unfair practices of child labor.

Child labor masked as an apprenticeship

Apprenticeships are one of those things that seem like a good idea. Tradesmen got help, and children got the training they needed to make their own living as adults. Right?

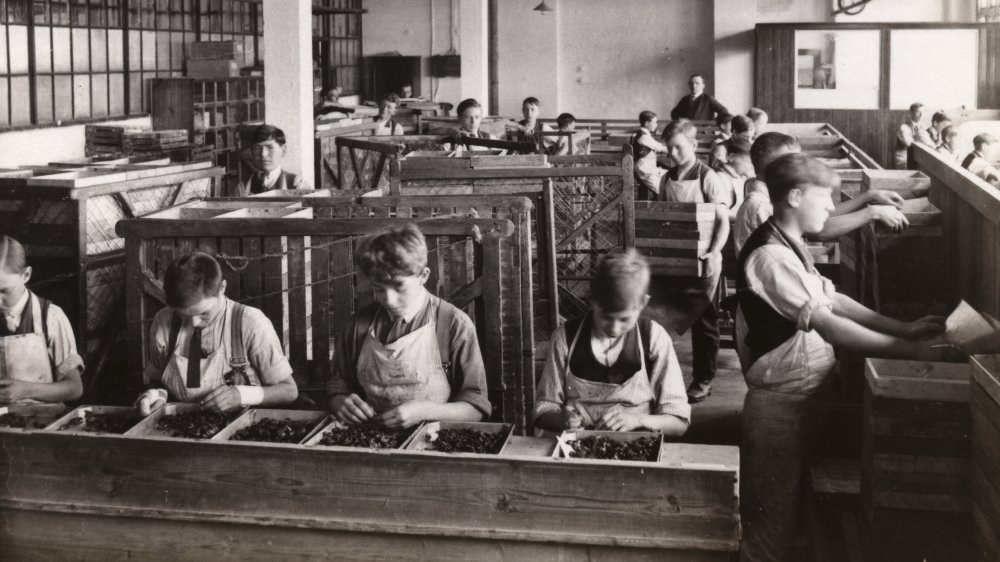

Not quite. Let's take just one example (via Spartacus). In 1799, the owner of a massive cotton mill was facing a labor shortage, so he courted the St. Pancras Workhouse with some amazing promises. The children who wanted to come and learn the trade "would be transformed into ladies and gentlemen," fed well, paid well, and generally treated well. About 80 children headed to the mill, and when they got there, it was an entirely different story. It wasn't quite the plum pudding and beef that was promised: Boys and girls held up their dirty shirts and aprons and were served a few boiled potatoes in their greasy clothes, then ran off to eat them before someone could steal their meager rations.

They were the pauper apprentices, and contracts were signed by workhouses, industry owners, and the children themselves, binding them to service until they were 21 years old. Children were typically between 10 and 13 years old when they signed, and the owners of the mills were paid for each child they took on. In theory, it was to pay for the care of the children, but given that an average of 90 children could be housed for a third of the cost of an adult family of workers, it's safe to say it was a pretty good deal for the industry.

Child migration and forced labor

In 1618, Britain started another practice: taking poor children off their streets and shipping them off to their colonies to fill labor shortages there. According to Merseyside Maritime's On Their Own, that first instance was a case of 100 children picked up in London and given to the Virginia Company, who sent them to Virginia's plantations. And it happened a lot: 200 kids were sent over to North America in 1645 to fill in where there were more labor shortages, and in the 1740s, around 500 children were kidnapped from Scotland and sent to the colonies. Their story was later documented in the 1757 book written by one of the children, Peter Williamson. Did it stop the practice? Of course not!

Fast forward a bit, and we come to the establishment of the Children's Friend Society. Sounds lovely, right? Actually, when it was founded in 1830, it was called the Society for the Suppression of Juvenile Vagrancy, and in the following decades, they were in charge of shipping around 80,000 boys off to Canada, per the Liverpool Museum, and later on, Australia.

According to the BBC, while it was believed the practice ended in 1967 (not a typo), Rex Wade and his younger brother were shipped from Cornwall to Tasmania — where they worked in a care home — in 1970.

The matchstick makers and phossy jaw

During the Victorian era, one of the largest employers of women and young children was the matchmaking industry — and that's not a 19th-century version of a dating service, it's literally the process of making matches. It was a tedious job that involved dipping treated sticks into a phosphorus concoction, then drying and cutting them into matchsticks. Doesn't sound awful? There was a terrible side effect.

According to Mental Floss, many of those working in the cramped, stuffy conditions of the matchstick factories were pre-teen children. Not only did their workplace conditions make them susceptible to things like rickets and tuberculosis, but matchstick-makers suffered from a specific illness called phossy jaw.

Phossy jaw happened to around 11% of workers exposed to regular, dangerous amounts of phosphorus, and it's essentially a disfiguring infection in the jawbone that led to swelling and a "foul discharge from the mouth [...] that would have been odorous." The disfigurement of phossy jaw was often compared to leprosy, and even though the effects of exposing women and children to such high levels of phosphorus were well known in the 1800s, it wasn't banned until 1910.

The horrors of chimney sweep child labor

The more you learn about the life of a chimney sweep, the more awful it gets. Owlcation says that chimney sweep apprentices — particularly those in the big cities during the Industrial Revolution and the Victorian era — suffered unimaginable abuse.

Why was abuse so rampant? For starters, there were so many people flooding into the cities that master sweeps could pick and choose the children they wanted. Given that they were sending them into narrow, winding chimneys that averaged around 9 square inches, the smaller and younger children were the ones who got the jobs. Then, they were continuously underfed to help make sure the master sweep could get as many years of child labor out of them as he could.

Children were expected to clean up to 20 chimneys a day, find clients for the master sweep in between jobs, and use their one and only blanket to collect the soot and take it back to the master sweep's courtyard, where it was then sold as fertilizer. (Yes, that was the blanket they then slept under.) Deaths from suffocation weren't uncommon, and male chimney sweeps that survived to puberty would often pay a terrible price: Some developed scrotal cancer, which was appropriately called chimney sweep's cancer.

Child trafficking was alive and well in Victorian England

In 1885, William T. Stead published a three-part series called The Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon. When he did, Owlcation says he exposed a whole other section of child labor: sex work.

Stead did an insane bit of undercover work to do it, too. He headed into London's East End and started asking around to see who was going to point him in the direction of procuring a young, virgin girl for ... reasons. The specific girl in question was named Eliza Armstrong, and she was purchased from her mother for what's now equivalent to just under $600. Standard practice, Stead wrote, was to incapacitate the girl with chloroform, then the buyer could do whatever he pleased. Instead, he handed the girl over to the care of the Salvation Army.

It was a shockingly widespread problem. In 1848, 2,700 girls between 11 and 16 were hospitalized for treatment of various STDs, mostly contracted as a result of their trade as sex workers. By the end of the century, it was well-known that there was a certain stretch of Pentonville Road where someone could go to find a girl around 13 or 14. The Guardian reported that in 1885, Parliament did respond to Stead's article and raised the age of consent to 16.

Some children preferred working to being at home

In 1840, Lord Ashley — who later became the Earl of Shaftesbury — set up the Children's Employment Commission to try to determine just how widespread child labor was. The commission's first report was released in 1842 and contained interviews with 1,500 children. While there were a lot of horrible stories, there were also a lot of children who said they preferred to be at work over being at home.

They were children like Philip Hughes, who was nine years old when he was working at a printer in Dublin. He said (via The Guardian) that even though they sometimes got "slaps on the head," "they are not allowed to beat us." Then he added that he "would rather stay here than at home."

He wasn't alone. Hannah Clarkson, for example, said (via My Learning) that she was ten when she first went into the coal pits, and "I like going to the pit, but I would rather go to service. [...] If I had a girl of my own I would rather send her to the pit than clam (hunger), but if I had the choice I would rather send her to some other work."

Why on earth would children look the least bit favorably on their conditions? Historian Ian Galbraith says: "Very often it was far better to be in the workplace where you would be warm and fed, rather than at home, where conditions were far more cramped and squalid."

There were some large-scale tragedies

Yes, children died on the job. And sometimes, the tragedies that took the lives of some of the world's youngest workers happened on a huge scale.

In 1838, 50 children were working alongside 33 adults at the Huskar mine in Silkstone. They included 7-year-old Joseph Burkinshaw, 8-year old Sarah Newton, and 9-year-old Ann Moss (via Historic England). The beautiful July day turned awful, and by early afternoon, violent thunderstorms moved through so fast and so furious that local rivers and streams overflowed their banks. Miners started to fear that the pit, too, would flood, and according to Around Town, the engine and boiler were flooded. That meant workers needed to be winched out, and the pit boss ordered everyone to wait.

A handful of the children decided to try to escape on their own, including two of the Wright brothers. Their father had died in a mine accident the previous year, and eager to avoid the same fate, they started climbing through the shafts. When a stream at the surface overflowed and flooded the tunnel, 26 children were trapped. They were between 7 and 17 years old, the official ruling was "accidental death by drowning," and they were buried together in seven graves. The accident led to the establishment of the Royal Commission of Enquiry, and new legislation would forbid women and girls from working in the mine, and set a minimum age of 10 for boys.

Changing child labor laws in the US

According to Betsy Wood, a history professor at Hudson County Community College (via The Conversation), the question of whether or not children should work was argued for decades after the Civil War. And it was largely a case of North vs. South: Northern states condemned child labor because it made it harder for adults to find jobs, while the South needed those kids in the fields and in the mines. By 1900, around 25,000 of the South's textile workers were under the age of 16.

Northern reformers were all over that, painting a dismal picture of "white child slavery," even as the South cried "aggressive Northern interference." In the following years, groups claimed child labor "weakened the white race and, therefore, interfered with US plans for global dominance."

Arguments went on for a long time. In 1918, the Supreme Court even upheld an earlier verdict that confirmed that yes, a parent did have the right to ensure their children were employed. It wasn't until the Great Depression that people generally got on a similar page about child labor (or, more accurately, they were at least reading from the same book). It was widely agreed that what jobs were available should be given to adults, and it wasn't until 1938 that the US saw the establishment of the first child labor law the Supreme Court didn't overturn. Children not working? It's a new-fangled thing.