The Untold Truth Of Ma Rainey

Gertrude "Ma" Rainey was undoubtedly one of the greatest blues performers of all time. Not only did her voice captivate audiences, but she had such a stage presence that audiences were absolutely mesmerized and always kept clamoring for more. Her band leader "Georgia Tom" Dorsey once recalled, "She possessed her listeners: they swayed, they rocked, they moaned and groaned, as they felt the blues with her."

What is known as classic blues originated in the Deep South, developing out of country blues and transforming through Black church music and African musical customs. And Rainey not only developed her own style of blues, but she essentially established the genre as we know it.

Like many blues songs, many of her songs focused on the woes of romantic relationships. But her songs were subversive as well as heart-breakingly beautiful. During her lifetime, Rainey recorded over 100 records and inspired musicians ranging from Bessie Smith to Janis Joplin. This is the untold truth of Ma Rainey.

Ma Rainey performed from a young age

Gertrude "Ma" Rainey, born Gertrude Malissa Nix Pridgett, was most likely, and by her own account, born on April 26, 1886, in Columbus, Georgia. But according to The New York Times, a census taken in 1900 lists her birthdate as September 1882 and her birthplace as Alabama. Rainey was one of five children, and her parents, Thomas Pridgett Sr. and Ella Allen-Pridgett, were both minstrel troupers. But after her father died in 1896, Raniey's mother took a job with the Central Railway of Georgia.

According to The Crisis, Rainey began singing when she was 12 years old, but her family is known to have said that Rainey was "singin' soon as she was talkin'," and very soon, she was performing. Her first known show was at Columbus' Springer Opera House in 1900, where Rainey sang and danced in "A Bunch of Blackberries," a local talent show.

Soon after her first performance, Rainey started traveling and performing in minstrel and vaudeville shows.

The history of all-Black minstrel shows

A form of entertainment in the United States, minstrel shows developed in the early 1800s. A series of music, dance, and comedy performances, they were also intended to inform audiences about the important issues at the time, and one of the main topics of minstrel shows was race. Black people and Asian people were repeatedly depicted as inferior and peculiar in sketches that used blackface.

But white people weren't the only ones doing minstrel shows. According to Brown University's Center for Digital Scholarship, the first Black minstrel troupes began performing around the 1850s, but they especially multiplied after the Civil War. These troupes also wore blackface and were even claimed to be more "authentic" representations of Black people than the versions depicted by white people.

While all-Black minstrel troupes followed the form of white minstrel scenes, they often had a satirical edge to them, rivaling the typical depictions of Black people as "fools." And according to Blacking Up by Robert C. Toll, "in the 19th century, minstrelsy was [Black people's] only chance to make a regular living as entertainers, musicians, actors or composers."

Marriage to Pa

Before long, Gertrude caught the attention of William "Pa" Rainey, another traveling showman, and in 1904, they married. They started touring together, billing themselves as "Rainey and Rainey, Assassinators of the Blues," joining up with many different groups, such as the Tolliver Circus and F. S. Wolcott's Rabbit Foot Minstrels.

According to the Oxford African American Studies Center, Rainey toured with Pa until their marriage ended in 1916. And all throughout this time, she was developing the classic blues singing, contributing directly to its evolution. According to Deep Blues by Robert Palmer, Rainey became exposed to blues for the first time in 1902 in a small Missouri town. She heard a girl near the tent singing a song about how her man left her that was "strange and poignant." Rainey incorporated the song into her act, and after the overwhelming response from rural Black audiences, she began using more and more blues songs in her routines.

And according to BlackPast, their shows were much more than just musical performances. They often included comedy and drama routines as well, a technique that was typical of Black musicians and blues performers of the period.

Ma Rainey, the Mother of the Blues

As Ma Rainey toured, she developed her version of the blues, blending together early jazz and country blues with her own musical style. According to Dan Morgenstern, quoted in the Chicago Tribune, "What today is called 'classic' blues style came into being when young Gertrude Rainey, impressed and moved by her first encounter with country blues, made this 'folk' music part of her more sophisticated, professional performance routine."

According to Rainey's pianist and music director "Georgia Tom" Dorsey, "Ma had the audience in the palm of her hand. [...] When Ma had sung her last number and the grand finale, we took seven [curtain] calls." Her performances stunned people. And after ending her marriage with Pa, Rainey established and toured with her own band named "Madame Gertrude Rainey and her Georgia Smart Sets."

Rainey's performances were so staggering that Paramount rushed to sign her and get her into a recording studio. By 1923, when she'd been signed by Paramount Records, she'd be billed as the "Mother of the Blues."

Sparkling in the spotlight

The audio recordings of Ma Rainey don't do her justice. According to the Huntington Theatre Company, her live performances were considered to be unforgettable. Wearing elegant sequin gowns along with diamonds and necklaces, including her trademark necklace made out of $20 gold coins that earned her the nickname "The Golden Necklace of the Blues," Rainey had a commanding hold over her audience. The gold in her teeth was even said to sparkle.

According to Understanding August Wilson by Mary L. Bogumil, Rainey was "recognized as a flamboyant songstress, adorned by her own spectacular creations, jewels and costumes." Georgia Tom recalled how "Her diamonds flashed like sparks of fire falling from her fingers. The gold-piece necklace lay like a golden armor covering her chest."

According to "Staging the Blues" by Claire Gauen, Rainey also knew how to make an entrance. She began her stage shows by being wheeled out inside a giant prop Victrola, and after a chorus girl took a prop record and placed it onto the phonograph, she would begin singing from inside. Then, at a song's climax, she would emerge from the phonograph. Audiences went wild!

Ma Rainey's influence on Bessie Smith

It's unclear exactly when or in which minstrel troupe, but sometime between 1913 and 1916, in either The Rabbit Foot Minstrels or Moses Stokes, Rainey became acquainted with Bessie Smith. Smith joined the troupe that Rainey was traveling with, and the two became fast friends, changing Smith's life forever.

According to The New York Times, at the time, Smith was only performing as a chorus girl, but Rainey quickly took her under her wing. Rainey liked Smith and taught her about life on the road in addition to giving her music lessons. However, the two women ultimately ended up with different styles. While Rainey's voice was striking and raw, Smith was comparatively more subtle and earthy. And before long, the "Mother of the Blues" had given birth to the "Empress of the Blues."

It's also likely that Rainey and Smith had a romantic relationship. They were both openly queer, and after Rainey was arrested during a police raid in 1925 in which she was found in the company of several women naked and having sex, Smith was the one to bail her out of jail. And according to Atlas Obscura, Sam Chatmon, one of Rainey's guitarists, said that based on the way they talked, it sure seemed like Rainey was "courtin' Bessie [Smith]."

Ma Rainey, queer queen

After her divorce from Pa, Ma Rainey is considered to have openly identified as queer. While it may not have technically been public knowledge, she didn't try very hard to hide it. Some sources claim that she was married twice, though not much is known about her second husband, and she's known to have had a number of relationships with women.

Rainey didn't shy away from singing about queerness. "Bull Dyker's Dream," sometimes disguised as "B.D. Women" or "B. D.'s Dream," is described as a lesbian song, while "Sissy Blues" recounts a story of a woman's man leaving her for a beautiful trans woman. However, some of the lyrics upheld stereotypes of the time.

She recounts her arrest in "Prove it on me Blues," singing richly, "I went out last night with a crowd of my friends,/ It must've been women, 'cause I don't like no men./ Wear my clothes just like a fan/ Talk to the gals just like any old man." Ultimately, Rainey was able to get away with her lyrics by switching back and forth between being subversive while simultaneously acknowledging with the audience the subversive nature of the acts.

According to Out History, the advertisement for the song featured a large woman in a tie, vest, and suit jacket with her skirt talking to two women in comparatively more feminine attire as a policeman watches. Rainey herself was known to dress more butch offstage compared to her femme outfits onstage.

Integrated shows

Even before Paramount signed her in 1923, Ma Rainey was wildly popular. By 1917, her shows were completely packed, sometimes not just by all-Black audiences. According to "'See See Rider Blues' – Gertrude 'Ma' Rainey" by Jas Obrecht, some of her shows were integrated, with half of the tent reserved for Black people and half of the tent reserved for white people. And selling out integrated shows wasn't a usual occurrence during that time, especially in the Jim Crow South.

If there was overflow, sometimes people sat in mixed audiences because nothing was worth missing her performance. Her songs were full of heartbreak and abandonment, and sometimes when she moaned, audiences moaned along with her. According to Atlas Obscura, sometimes Rainey was also hired by white people to play quieter private parties. But she'd always head to a local Black café straight afterward to dance after a night's work.

Ma Rainey's contract with Paramount Records

Three years after Mamie Smith and The Jazz Hounds (pictured above) produced the first blues records in 1920, Paramount records signed Rainey. She recorded with Paramount until 1928, during which time she produced almost 100 records/songs, including classics such as "Bo Weavil Blues," "C.C. Rider," and "Dead Drunk Blues."

Rainey's early albums were so successful that she was part of Paramount's 1924 promotional tour, and her popularity only spread from there. According to ThoughtCo, after having started out touring in the South, the success of her music brought her to tour in the North in cities like New York City and Chicago. In addition to her backup band, the Wildcats Jazz Band, Rainey performed with some of the most talented musicians of her time, including Lovie Austin, Coleman Hawkins, and Louis Armstrong. Rainey toured with the Wild Jazz Cats until 1926, after which she recorded with a variety of musicians under the name "Ma Rainey and her Georgia Jazz Band."

Rainey also reportedly earned a reputation of being as savvy a businesswoman as she was a performer, but despite her frugality, she was known as someone who was always willing to help out with money if she could. She also invested some of her earnings in several movie theaters back home in Columbus, Georgia, to which she would return to after her touring career concluded.

The feminism of Ma Rainey's lyrics

Despite their heartbreaking nature, for the blues is the blues, Rainey's lyrics, many of which she wrote herself, gave agency to the women protagonists in her songs, who don't repent for acting as undesirably as men do. According to Georgia Women by Ann Short Chirhart and Kathleen Ann Clark, while some of her protagonists recounted abusive lovers that they couldn't tear themselves away from, others responded to violence with violence. But Rainey's music explored the multiplicity that arises in broken relationships.

Singing to mainly poor, rural Black audiences, Rainey sang of troubles with drinking, with the law, with sexual brutality, and with loneliness. And her performances were especially moving to those who saw such a striking figure sing of their own troubles.

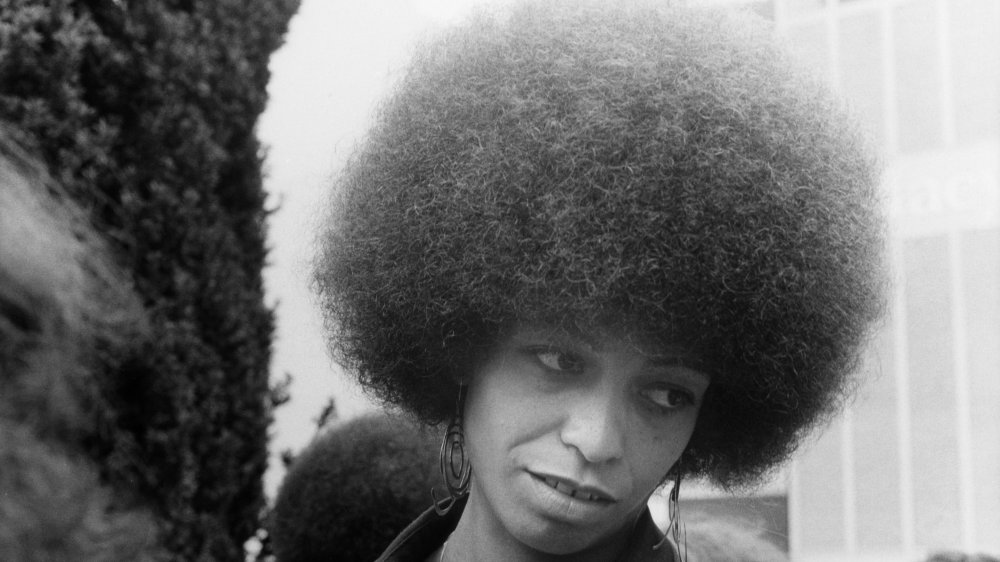

And according to Blues Legacies and Black Feminism by Angela Y. Davis (pictured above), her work was firmly anchored in Southern Black culture as it evolved against a history of enslavement. Rainey was just one generation removed from slavery, and as contemporary blues singer Koko Taylor has said, "What these women did — like Ma Rainey — they was the foundation of the blues. They brought the blues up from slavery up to today." During the racial segregation of a post-slavery system, Rainey existed unapologetically as a Black queer woman. And with songs like "Bull Dyker's Dream," she responded to the prevailing racism, homophobia, and sexism of the time by disrupting heteronormative and cisnormative notions with her masculine lyrics.

Ma Rainey steps back from the blues

During the Great Depression, entertainers were hit with financial difficulties, but blues performers especially suffered as new styles of jazz started to become more popular and record companies dropped blues performers in search of more profit. According to Women & Music: A History by Karin Pendle, Paramount refused to renew Rainey's contract because they claimed that "her style of down-home singing and the blues had gone out of fashion." By that point, vaudeville circuits had also started to decline, and Rainey resorted to playing primarily tent shows.

Despite this, her career was not immediately affected, and she was earning enough to continue touring in her own bus, complete with her name painted on the side. But ultimately, Rainey was unwilling to adapt her style to fit in with the fads that the record companies were interested in. After her sister and mother died, Rainey retired from music, returning to her hometown of Columbus, Georgia, in 1935. Having invested in several movie theaters, she owned and operated the Lyric and Airdome theaters in addition to devoting herself to church and charity work.

Unfortunately, Rainey's life was cut tragically short in 1939, when she died of a heart attack in Rome, Georgia, on December 22 at the age of 53. Despite everything she'd accomplished, her death certificate and local obituaries listed her occupation as "housekeeper."

Ma Rainey's legacy

Ma Rainey's legacy in art can't be understated, and her loss was soon felt in the artistic community. Within one year of her death, Memphis Minnie recorded the first tribute song to Rainey, proclaiming in the lyrics that "she was the best blues singer, peoples, I ever heard." In addition to her influence on Bessie Smith, her records inspired generations of musicians like Billie Holiday, Dinah Washington, Big Mama Thornton, and Koko Taylor. Janis Joplin also adored Ma Rainey and Bessie Smith as blues pioneers and listened to her avidly.

Rainey's influence also rippled through the literary world. According to ThoughtCo, multiple poets such as Sterling Allen Brown and Langston Hughes refer to her in their writings. And her life is the topic of the 1982 play Ma Rainey's Black Bottom by August Wilson, although the play is not an entirely biographical depiction. According to The New York Times, when Alice Walker was writing The Color Purple, she listened to a great deal of Rainey and Smith's music: "They showed you had a whole self and you were not to succumb to being somebody else's — as they would say — 'play toy.'"

Rainey wouldn't be inducted into the Blues Foundation Hall of Fame until 1983, and in 1990, she was also inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as an early influence. Her Columbus house also has historical landmark status and is home to The Gertrude "Ma" Rainey House & Blues Museum.