What It Was Like The Day The Berlin Wall Fell

The fall of the Berlin Wall is one of those momentous occasions that feels both recent and timeless simultaneously. Perhaps the reason why it is so iconic and still spoken of with such awe and excitement is the fact that, apparently, almost nobody saw it coming.

The sudden events of the evening of November 9, 1989, were extraordinary precisely because they were so surprising. In addition, they were miraculous in that one of the greatest and most seismic desegregations of contested land was actualized by regular citizens on the ground, and the whole thing occurred entirely peacefully.

Today, we can only look back and wonder at the fact that things turned out as they did. For those of us who weren't there at the time or were perhaps too young to appreciate it, we can only imagine what that day felt like to regular Germans who had been separated from their loved ones for so long. This is the story of what that day felt like for those who lived through it.

All quiet on the Western side

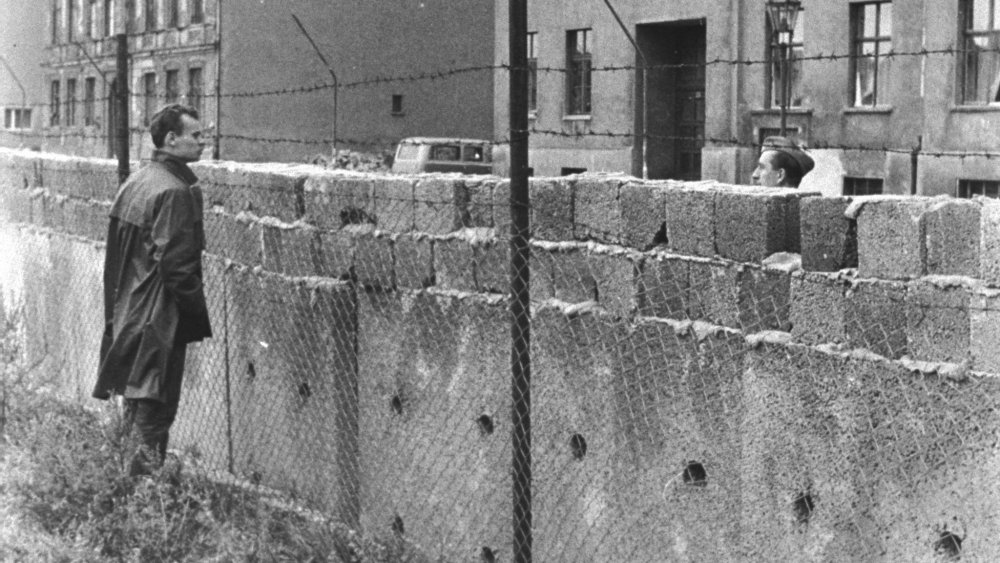

The morning of November 9, 1989, was like any other for most Germans on either side of the wall. For all intents and purposes, the same division existed from when the city was split into West and East sectors by the Allied Powers in the aftermath of World War II. The Wessis and Ossis – as the citizens of the west and east sectors of the city were respectively known, had been divided ideologically since 1949, when the city was segregated with the formation the western Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) and the eastern German Democratic Republic (GDR). From 1961, the city had also been split by a physical barrier, the Berlin Wall, which the GDR began constructing by surprise on the night of August 13, ostensibly to slow the tide of East Germans escaping to the more prosperous and free FRG, according to the GDR Museum.

From then on, the Berlin Wall remained heavily guarded, with patrol guards, attack dogs, and, according to National Geographic, 55,000 active landmines. By 1989, crossing the wall had been a difficult venture for nearly three decades. Being granted legal passage was rare. Instead, many easterners attempted to escape to the West by their own means. As recently as March 8, 1989, Winfried Freudenberg had died in a balloon crash attempting to escape East Germany.

In November, the same military deterrents were in place to prevent people from crossing. But all that was about to suddenly change.

The East's popular uprising

Life in the GDR had been brutal for many, "characterized by shortages, spying and fear," according to the GDR Museum. But after decades of living under what was essentially a dictatorship, the East German populace was making its anger known. On November 4, 1989, more than half a million East Germans gathered in the streets to demand free elections, according to CNN.

Their demonstrations proved impactful. The ruling party of the GDR was already losing political sway amid the economic and political turmoil of the entire Eastern Bloc. The result was the passing of preliminary laws allowing a certain degree of free travel and also the resignation of Prime Minister Willi Stoph and his entire 44-strong East German cabinet on November 13. On the same day, more than half of the GDR Politburo were removed from their seats.

Change was certainly in the air that November, but nobody in the East — or West, for that matter — was expecting what came on November 9, when the Iron Curtain finally swung open.

The Schabowski press conference

The press conference given by Günter Schabowski, a senior member of the GDR Politburo, on the evening of November 9, 1989, has gone down as one of the most notorious and seismic in world history, triggering the start of the reunification of a scarred city and changing the lives of German citizens on both sides of the wall forever.

Schabowski had been a longtime official for the East German Socialist Unity Party of East Germany (SED) by 1989 and had recently been instrumental in the ousting of the party leader, Erich Honecker, in favor of Egon Krenz. It is believed that, at the time of his vital mistake, Schabowski was one of the most powerful people in the GDR.

His press conference was set to go like any other, announcing the loosening of travel restrictions as a consequence of the popular protests that had swamped the GDR. The conference was meant to present an "incremental change in policy." However, according to Time, Schabowski, who misread his notes, announced that, "Permanent relocation can be done through all border checkpoints between the GDR into the FRG or West Berlin." One journalist asked when the regulations would take effect, and Schabowski replied, "As far as I know, it takes effect immediately, without delay." For all intents and purposes, this meant that East Germans could pass directly into the West without restrictions for the first time in nearly three decades.

The evening headlines

As told by The Washington Post, Schabowski's famous bungled messaging regarding travel occurred at a few minutes before 7:00 PM, in front of dozens of assorted journalists. One of them, Tom Brokaw, later said that Schabowski's announcement felt like "a signal had come from outer space and electrified the room." According to the Berlin Times, in East Germany, footage of his announcement went out just minutes later, at 7:17, on the ZDF network and then at 8:00 on the West German ARD.

Reportedly, these early announcements were tentative. Did Schabowski really mean what he had said? He did not back down from his mistake. EURACTIV reports he told the amazed journalists: "I am not quite sure but I was told that this information was forwarded to you already. I suppose you have got this release already." According to Time, news anchorman Hanns Joachim Friedrichs (pictured, left) told the audience: "This 9 November is a historic day. The GDR has announced that, starting immediately, its borders are open to everyone. The gates in the Wall stand open wide."

A standoff at the Berlin Wall

The East German border guards patrolling the Berlin Wall were entirely unaware of the events of the Schabowski press conference. Matters could easily have gotten out of hand when, shortly after the announcement of free travel into West Berlin was broadcast, citizens on both sides of the wall began to descend upon the border in huge numbers, demanding that the checkpoints be opened. However, confusion still reigned, and for all intents and purposes, the Berlin Wall was still standing — and deadly.

Lt. Col. Harald Jäger was the Stasi officer in charge of the Bornholmerstrasse checkpoint, and, according to The Washington Post, had been in his job for 25 years on the night that the wall fell. His loyalty to the regime had been unwavering, and after watching Schabowski's interview on television, he described the Politburo member's words as "deranged." Once on duty — and having attempted to get some clarification on the border situation via phone calls with his superiors — Jäger found himself trying to convince the swelling and increasingly impatient crowd that border crossing was still forbidden. Like the guards at every checkpoint along the wall, Jäger and his men were armed, but no one in his command chain was willing to authorize the use of force against the East German crowds.

The timing of Schabowski's press conference was crucial to how events turned out, as many senior officers were already asleep as events escalated, leaving people like Jäger to take things into their own hands.

The Berlin Wall guards stand down

With the benefit of hindsight, many journalists and historians have pinpointed the involvement of Harald Jäger as being pivotal to avoiding bloodshed on the day the Berlin Wall fell.

The crowds continued to gather and press the guards at the checkpoints as the night went on. Years later, Jäger spoke to Al Jazeera about the events of that night and his role in defusing what could have been a powder keg of violence in the wrong hands. Crucially, he speaks of his mixed feelings on the night of November 9: "It was the best night and the worst night."

After a lifetime of loyalty to the GDR, Jäger recalled that, "The worst part was that I felt completely abandoned by my superiors. I was left in the lurch." With no direction from those in charge, Jäger and his men began to allow handfuls of the loudest agitators to pass over into the West, according to The Washington Post. While hoping that this would relieve the pressure on the situation, Jäger realized he had only increased the crowd's fervor for freedom, as thousands began to chant, "Open the Gate! Open the Gate!" at the beleaguered border guards.

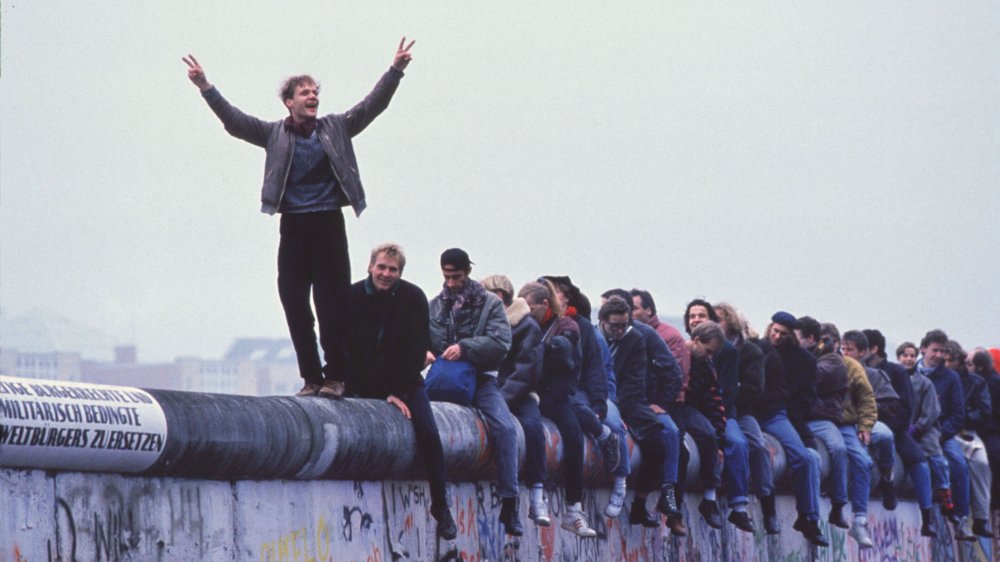

Vastly outnumbered and realizing that the tide was against them, Jäger and his men opened the Bornholmerstrasse checkpoint, allowing German citizens to pass freely, and stood down from their posts.

The first crossings of the Berlin Wall

Fambrizio Bensch – who became a journalist with Reuters a few years after the fall of the Berlin Wall — was waiting on the Western side of the wall with thousands of others at Checkpoint Charlie shortly after hearing the announcement that the checkpoints were open. By 9:00 PM, the Eastern side was still empty. Perhaps they had been misinformed? Perhaps the East had cracked down on their citizens? The information was so thin on the ground that nobody could tell for sure.

Then came the sight of a lone East German, running through the checkpoint with his blue GDR passport held aloft. Bensch reports that the man, upon seeing the crowd gathered to meet him, fell into the arms of strangers and burst into tears. All along the well, strangers were celebrating together with food and champagne, treating the occasion like a reunion with long lost family members — in many cases, this was exactly what it was.

Thirty years after that momentous day, Pastor Werner Krätschell, a GDR dissident who later found out that his phones had been bugged by the Stasi, shared his memories with The New York Times. He, his daughter, and her 21-year-old friend who was pregnant at the time and had never set foot in West Germany, found the moment irresistible. They piled into the Pastor's yellow Wartburg and headed to the West. Krätschell said the moment felt like landing on the Moon.

Bring out the sledgehammers

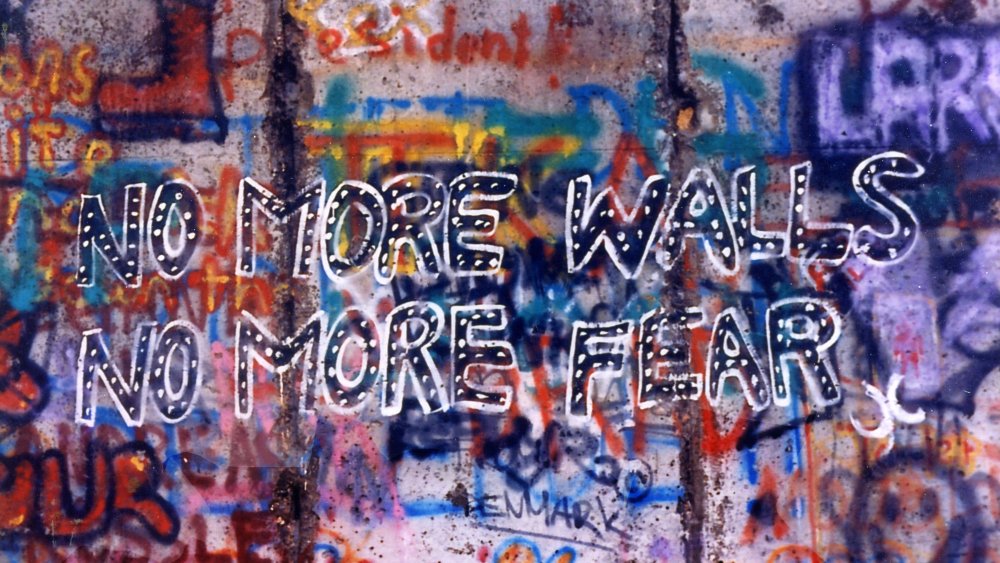

Every picture of the fall of the Berlin Wall bristles with the electricity of the occasion. Today, we are treated to a vast array of images that capture the spirit of the occasion and the joyous sense of togetherness that descended upon a city that had been segregated for so ruthlessly for so long.

Almost every image of that day is iconic. However, those that have the most symbolic resonance for us today are perhaps those of ordinary Berliners destroying the physical barrier that had so long stood between them and their neighbors: the wall itself. Using household tools such as chisels as well as heavy-duty sledgehammers, people began to break the wall down piece by piece. These people, who have earned the German name mauerspechte, or "wall woodpeckers" according to History.com, have come to populate some of the most defining images of the events of November 9, 1989, the day when the power transferred from the oppressive GDR government to — literally — the hands of the people.

An ecstatic occasion

Most street parties are boozy affairs, and it's no secret that Germans are, in general, fond of the beers for which they are famous. But although many East Berliners were met with champagne on their arrival in the West, most sources report that November 9, 1989, was mainly a sober gathering, propelled by the communal ecstasy of the occasion. As Reuters described it, the fall of the Berlin Wall was the gathering of "strangers united in a euphoric moment."

More so than booze, it was the basic foodstuffs that East Berliners had been denied for so long that were gleefully shared and carried around as totems long into the night. Bananas especially became a key symbol of the new humble possibilities that were now open for East Berliners whose lives, up until that point, had been dominated by scarcity and food shortages.

The moment also opened the eyes of many East Berliners loyal to the GDR who had been assured that conditions in the East had not been so bad. "Thinking of how hard we'd worked all these years and how things weren't so bad," one East Berliner told Reuters, "I was dismayed to see capitalism is so far ahead."

Willy Brandt addresses the greatest street party in the world

Carousals continued into the next day, and, in total, more than two million people descended upon the wall before the weekend was through, enjoying the atmosphere and new freedoms that had suddenly become a reality. From the Brandenburg Gate and Potsdamer Platz to Bornholmerstrasse and Bernauerstrasse, the city was a basin of thawing tensions and explosive jubilance. While many took it upon themselves to demolish the wall by hand, others tearfully embraced one another in scenes of joyous unity.

The jubilant crowds were addressed at Schoneberg Town Hall by the Nobel Peace Prize-winning Willy Brandt, who was formerly the leader of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SDP) and the former chancellor of West Germany. According to Willy Brandt Biography, he told the crowd: "And now we are experiencing, and that is something grand — and I am thankful to the Lord God that I could witness this — we are experiencing the parts of Europe growing together again."

A famous detail of this occasion is that Brandt was warmly cheered on the occasion, whereas his successor onstage, Helmut Kohl, was widely booed. However, Kohl's role in keeping events on track cannot be understated. Years later, Reuters reported that Kohl had received a call from Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, who asked if the rumors were true that protesters were attacking Soviet military posts. Kohl, about to go onstage, was unable to check but assured Gorbachev that the rumors were false, avoiding potential military intervention in the process.

A 30-year party

Willy Brandt was one of the few politicians advocating for a quick and painless reunification in Germany, and that is exactly what he got. After East Germans overwhelmingly voted to merge with the West, the two formerly divided lands merged to officially form the Federal Republic of Germany on October 3, 1990.

By this time, much of the 156-kilometer wall had already been demolished. "You couldn't demolish it like that if you planned," said photographer Henrik Pastor, according to The Local. "In three days it was a mess, you couldn't take a photograph of it as used to be anywhere. It was over."

But in the former kill zones, barracks, and military warehouses that still stood along the former border between East and West Germany, parties, squats, and countercultural collectives were already beginning to form, building from the rubble the rudiments of the unconventional culture that would define the identity of the city to this day. From the world-famous Berghain club to the countless street parties, parades, and demonstrations that characterize the feel of everyday life in Berlin, the reverberations of November 9, 1989, are still felt and carried in the hearts of the city's unconventional and irrepressible populace.

Historian and travel writer Rory MacLean said: "Berlin is all about volatility. Its identity is based not on stability but on change." It is a quote that is true to this day.