The Untold Truth Of The Moulin Rouge

The year 1889 saw the opening of two Parisian landmarks that continue to draw crowds today. One was the Eiffel Tower, constructed for the opening of that year's Paris World's Fair, a display of science, art, and industry that would only be outdone by the incredible story of the 1893 World's Fair in Chicago. The second was frequented not by families and fairgoers but by the people who enjoyed the City of Light's darker side: the side that came out to party at night.

Over the next two decades, the Moulin Rouge became the most famous of the cabarets that welcomed bohemian beliefs, raunchy shows, and a level of mingling between social classes that had never been seen before. It made performers into stars and popularized one of the most scandalous dances of its day. But the fortunes of the club would rise and fall almost as fast and almost as often as a can-can dancer's leg. Over 130 years since the very first patrons swept onto its dancefloor, the Moulin Rouge has survived fire, two World Wars, and a near riot over a kiss. This is the untold truth of the Moulin Rouge, behind the scenes and under the spotlight.

The Moulin Rouge was colorful from the start

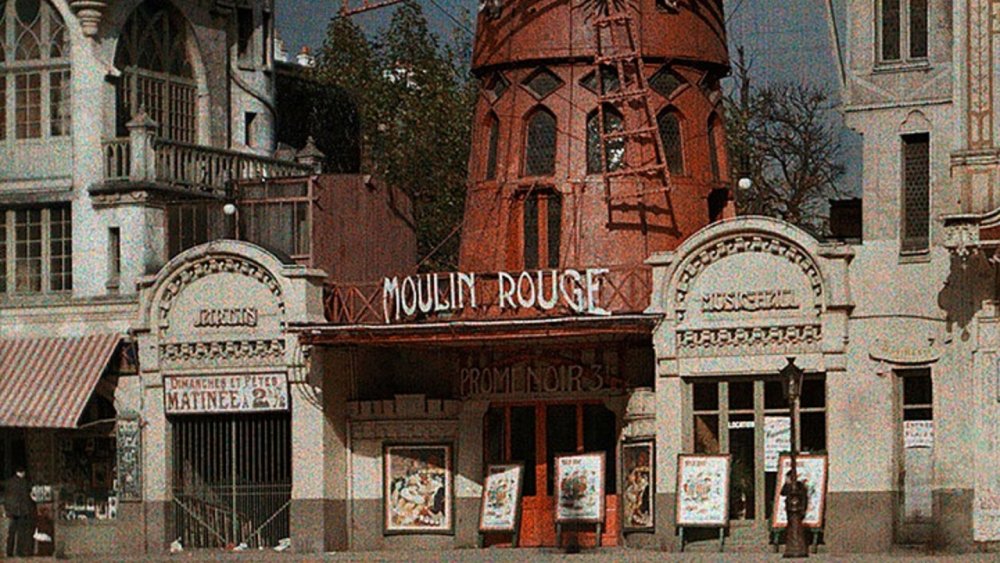

You'll still find the Moulin Rouge at 82 Boulevard de Clichy in Montmartre, Paris. Once a rural village famous for its windmills, vineyards, and narrow streets winding up and down steep hills, Montmartre was annexed by Paris in around 1860, according to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Artists, students, musicians, and other liberal-minded nonconformists were drawn to the area's low rents and revolutionary attitudes — and its anything-goes nightclubs.

The New York Times explains that in 1864, the city lifted restrictions that had made opening privately-owned theaters difficult, which led to a boom in cabaret and music venues. The area's windmills went from symbolizing its farming roots to a trademark of music halls like the Moulin de la Galette. Although Montmartre had traditionally been a working-class area, people of all classes met and mingled at the cabarets and cafes. By the time the Moulin Rouge opened, Montmartre had become a beacon for Parisians who wanted to escape rigid social structures and expectations.

The man who started the Moulin Rouge was Joseph Oller, a professional gambler and businessman who owned other nightclubs in the city, including the Olympia, the oldest music hall in Paris. According to the Moulin Rouge's website, the cabaret wasn't completed by the time of its planned opening on October 6, 1889, but Oller insisted that the show must go on, and opened at 8 pm sharp.

The Moulin Rouge promised many forms of entertainment

When you imagine a show at the Moulin Rouge today, you probably picture dancers doing the can-can in ruffled skirts. And the can-can was a big part of the venue's appeal right from the start, but the Moulin Rouge offered more than an onstage dance display.

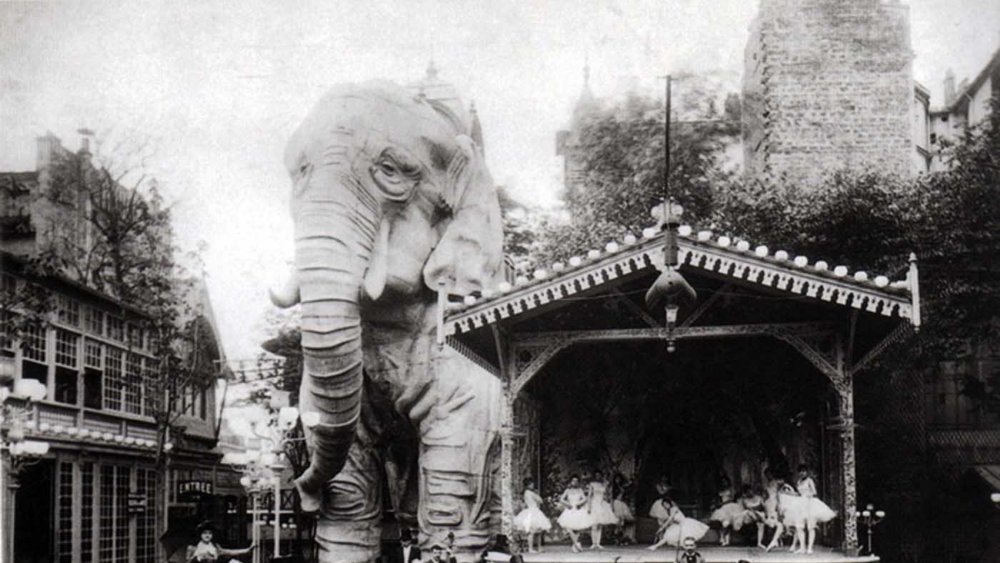

The main hall of the Moulin Rouge was designed by French architect Adolphe Willette, complete with chandeliers, mirrored walls, and a huge dance floor so that patrons as well as performers could show off their moves. Outside was the Jardin de Paris, a garden that boasted its own dance floor for long summer nights, and entertainment including donkey rides. It was all overlooked by a giant stucco elephant that Joseph Oller bought from the 1889 Paris World's Fair. If you've seen Baz Luhrmann's 2001 musical Moulin Rouge! you may remember that Nicole Kidman's character Satine greeted clients inside a giant elephant. But in real life, it was rumored to be used as an opium den.

As for the performers, there were clowns, acrobats, ballerinas, tightrope walkers, and singers, as well as can-can dancers. In keeping with the venue's status as a cabaret, the Guardian reports that the songs at the shows were usually funny rather than bawdy, at least during the Moulin Rouge's early days.

The Moulin Rouge is most famous for the can-can

The performance that's most associated with the Moulin Rouge is the high-kicking, quick-footed, audience-flashing can-can. The name can-can means scandal, and it supposedly evolved from part of another energetic dance, the quadrille, danced by couples at social events held in ballrooms belonging to the 19th century French elite. Part of the reason the can-can was considered so scandalous was the dancers' crotchless underwear.

Over time, the can-can gained followers among professional dancers, whose endorsements made it not exactly family friendly, but at least socially acceptable at dances. The New York Times reported that the can-can has been performed at the Moulin Rouge since it opened in 1889, and it's still the venue's most famous choreography. The moves made their way out of the line up: during those early days, a dancer nicknamed La Goulue would use her high-kicking skills to kick men's top hats off their heads.

The can-can eventually became a gimmick. According to the BBC, an early edition of the Oxford Companion to Music — first published in 1938 — described the can-can as "a boisterous and latterly indecorous dance... for the benefit of such British and American tourists as will pay well." And they're still paying, as are the dancers. The can-can is a notoriously dangerous dance that can break noses and rip tendons. And the split jump at the end is exactly as painful as it looks. One former Moulin Rouge dancer told the BBC, "We all screamed throughout!"

Toulouse-Lautrec gave us a glimpse into life at the Moulin Rouge

Henri-Marie-Raymond de Toulouse-Lautrec-Monfa — better known as Toulouse-Lautrec — left his aristocratic upbringing to enter the bohemian world of Montmartre in the mid-1880s. He first learned to draw as a child while recuperating from injuries to his legs, and studied under several noteworthy artists before striking out on his own to document the characters in Paris's underworld of cabarets, cafes, bars, and brothels.

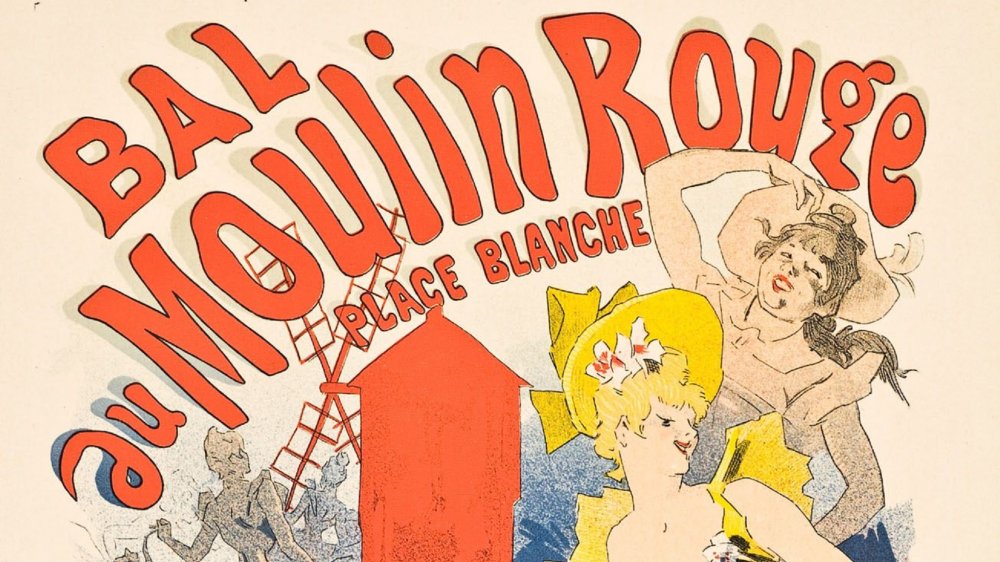

After gaining a reputation for his drawings throughout Montmartre, Toulouse-Lautrec was hired to create a poster for the Moulin Rouge in 1891. The image showed Moulin Rouge dancer La Goulue performing for a crowd, with the shape of a man in a top hat — likely her dance partner Valentin le Désossé — in the foreground. The poster was plastered all over Paris to promote the venue — and it also made Toulouse-Lautrec famous, landing him more gigs creating posters.

Toulouse-Lautrec became a Moulin Rouge fixture. The venue reserved a seat for him every night — the Guardian reports that the bar was his favorite spot — and he befriended the dancers and the sex workers who found clients among the patrons. Toulouse-Lautrec frequented the Montmartre brothels, and was so close to some of the madams that he occasionally stayed for months at a time. Today he is best known for his portraits of dancers and sex workers, showing them in an empathetic and non-judgmental yet unflinchingly honest light. Toulouse-Lautrec died in 1900, aged just 36, of complications from alcoholism and syphilis.

The Moulin Rouge went through a few iterations

In 1903, the Moulin Rouge got a makeover from architect Édouard Niermans, who aimed to update the now 14-year-old venue to attract Paris's most stylish patrons. But 12 years later, in 1915, disaster struck when the building burned down. It reopened in 1921, now focused on musical performances from famous stars like Maurice Chevalier and Mistinguett. The Moulin Rouge closed again in 1929, this time to transform into a cinema with a nightclub where the ballroom had been. It screened its first movie, Fox Movietone Follies, on December 8 that year, and caused yet another scandal: some viewers were so angry about the poorly written French subtitles that they vandalized the venue.

The Moulin Rouge stayed open during World War II, when it was frequented by occupying German officers — including high-ranking Nazi officials — as well as locals. One bright spark for the French audience was Edith Piaf, who started performing in the Moulin Rouge in 1944, just a few months before the city was liberated. The New York Times reported that she met her lover and future superstar Yves Montand there on February 18. Piaf escaped accusations of collaboration over her wartime performances, but many of the women who worked at the Moulin Rouge were punished for supposedly fraternizing with the enemy.

The Moulin Rouge was recreated yet again in 1951, when Georges France and Vincent Auriol restored it to its former life as a cabaret, while also hosting charity events.

The Moulin Rouge performers became stars

The Moulin Rouge helped turn dancers into Parisian superstars. In the early days, the queen of the can-can was Louise Weber, aka La Goulue or the glutton, since she had a habit of stealing patrons' drinks. Toulouse-Lautrec painted and drew her many times, and according to the Guardian, he later created panels for a booth she set up at a fair. La Goulue also lived exuberantly offstage, which sadly caught up with her: after serving a jail sentence she became a lion tamer, a traveling dancer, a laundress, and finally an alcoholic.

Another of Toulouse-Lautrec's favorites was Jane Avril, a red-headed dancer who had previously been a bareback horse rider in a circus before being hired to work at the Moulin Rouge. She was famous for her fast legs and sad expression that may have reflected her hard life and the time she spent in a mental institution.

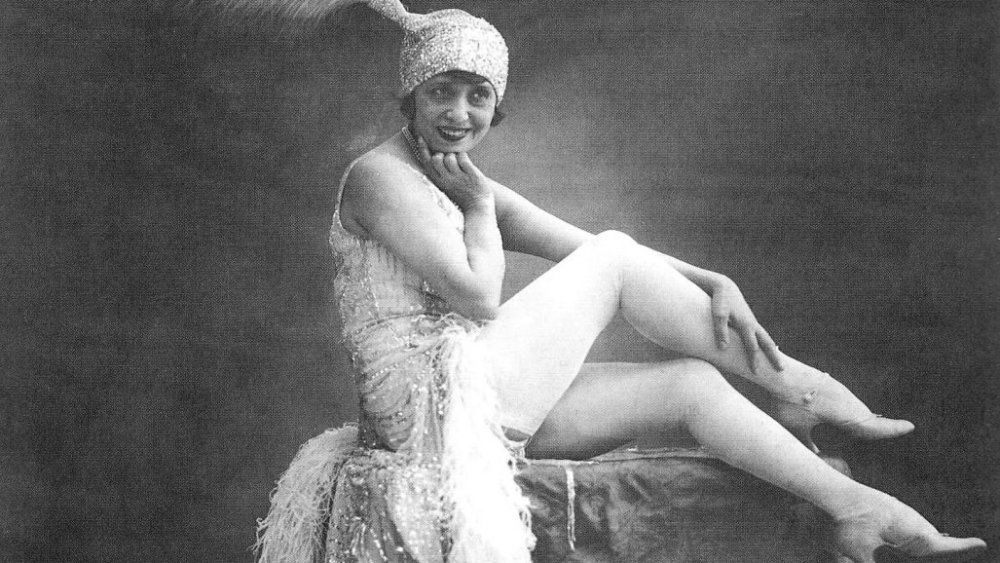

Of the generation of Moulin Rouge performers that succeeded Weber and Avril, the most famous was Mistinguett (pictured), born Jeanne-Marie Bourgeois. Mistinguett debuted on the Moulin Rouge stage in 1907 and quickly became the venue's star, thanks to her decadent shows that included songs, multiple costume changes, and semi-nudity. She was also famous for her legs — which she insured for $1 million, according to the New York Times.

The Moulin Rouge was also home to this very weird act

In addition to dancers and circus-style performances, the Moulin Rouge showcased a performer with a very unique talent. While serving in the French army, Joseph Pujol learned that he could inhale air through his, er, butthole, in the same way other people inhale air into their mouths. He realized this enabled him to rip truly epic farts, and he spent years honing his technique until he could control the release of the air over 10 to 15 seconds at a time. Kind of like whistling or humming, he could also control the volume and the pitch.

Pujol gave himself the nickname Le Pétomane — the Fartomaniac — and went on the road. He successfully auditioned for the Moulin Rouge in 1892, and after a few years, became a huge star. According to Caesar's Last Breath, extracted on Slate, Pujol would go on stage wearing a tuxedo and proceed to do impressions of members of the audience and celebrities, as well as animals. He could fart-play the flute and blow smoke rings. His finale was playing the French national anthem "La Marseillaise" and then blowing out a candle.

Audiences loved this immature humor. At least one audience member was reported to have had a heart attack during a Pujol performance, and corset-wearing ladies would occasionally pass out from laughing too hard. He became France's highest-paid performer. He retired in 1914 and died in 1945: his family refused an autopsy.

French writer Colette caused an onstage scandal

At the turn of the century, audiences flocked to the Moulin Rouge to see the supposedly scandalous can-can and to trample on social norms by mingling across social classes. But even these supposed rebels of their day were shocked by one performance in 1907.

Sidonie-Gabrielle Colette, better known by just her last name, was the most famous writer in France in the early 20th century — and her real life was even more adventurous than anything her characters got up to. Colette married three different men — and had an affair with the then-teenage son of one of those husbands — and she also had relationships with women. As the Guardian reports, her lover in the final six years of her first marriage was the Marquise de Belbeuf, nicknamed Missy. The two took to the stage of the Moulin Rouge in 1907 for an act called Rêve d'Égypte (Egyptian Dream), in which Missy played an archaeologist and Colette played a mummy. Colette unwound her bandages to reveal a jeweled bra, and then the two kissed.

The sight of two women kissing on stage nearly caused a riot among the outraged audience, and according to the Moulin Rouge's website, the chief of police threatened to close the cabaret down. The London Review of Books writes that Colette and Missy performed one more time and then their act was canceled.

The Moulin Rouge is alive and kicking today

We've all missed the Moulin Rouge's heyday as the bohemian center of turn-of-the-century Parisian nightlife, but the iconic cabaret is still open for business. In 2019, it celebrated its 130th anniversary — give or take a few years when it was closed for repairs. Today, the only people dancing are the performers: the audience sits at tables around the stage, enjoying dinner and champagne. Another change: children older than six are welcome. Tickets are over €100, and according to CBS, the venue is open 365 days a year, with 60 performers — including men and women — high-kicking their way through two shows six days a week. In addition to dancing, the New York Times reported that one section of "Féerie" — the show performed at the Moulin Rouge since 1999 — featured a live snake and a dancer in a water tank.

Sadly for a venue that was once the shining red light in the City of Lights, the Moulin Rouge is mostly seen by Parisians as a tourist trap today. Of the 600,000 visitors the venue draws in every year, half are foreigners.

Covid-19 has temporarily put an end to the close-quarters live performances that made the Moulin Rouge famous, but the venue's owners looked to a different aspect of its history. According to Vogue, in summer 2020 the Moulin Rouge continued its tradition of hosting an open-air rooftop cinema.

The Moulin Rouge was at the center of a racism scandal in 2003

There's nothing sexy about the scandal the Moulin Rouge walked into in 2003. The Independent reported that when Abdoulaye Marega, a Black man from Senegal, applied to work as a waiter at the cabaret, manager Micheline Beuzit told him that the Moulin Rouge only hired Black people in the kitchens, not in the public-facing theater.

Marega's case caught the attention of French anti-racism group SOS-Racisme, who sent another Black job applicant in to see if they'd receive the same treatment. That person was told the same thing. The group then sued on Marega's behalf, and in 2003, the Moulin Rouge was fined €6,800 (about $10,500 in today's money) which was split between Marega and SOS-Racisme. Beuzit was also personally fined €3,000 (nearly $4,700 today), but that was later halved at an appeals court, according to the Guardian.

The investigation found that the Moulin Rouge had not hired a non-white person as a waiter or performer for 40 years.

Being a Moulin Rouge dancer is a hard job

Moulin Rouge dancers make their moves look effortless, but underneath all the feathers, crystals, and ruffles they are working extremely hard. Even before you have to land the splits on stage, you have to land the job. The BBC writes that as many as 300 dancers audition for a job at the Moulin Rouge today. Former performer Stacey Kenealy told DanceLife in 2013 that her audition involved learning a long stretch of the show's choreography. After that, the dancers spend a month rehearsing. The can-can is the most physically demanding part of the show, and especially wearing on hip flexors. Warming up is essential: the dancers typically take 90 minutes to stretch and do their make-up before showtime. One way to get out of that part of the show, according to the BBC, is to go topless.

That might also help with another challenge the performers face. According to the Guardian, they only have about 90 seconds to change costumes between dances — and each dancer has 10 to 15 costumes in the show, making a total of about 1,000 outfits.

Luckily, the dancers are very supportive of each other. Moulin Rouge dancer Isabelle van den Bergh Cook — whose sister Claudine is a principal at the Moulin Rouge — told Glam, "We're all in here every night working together: I was surprised to find that it was actually a lovely atmosphere backstage."

Multiple filmmakers have depicted the Moulin Rouge onscreen

The glamour, scandal and characters at the heart of the Moulin Rouge's long history have made the cabaret the perfect setting for movies.

Directed by John Huston, 1952's Moulin Rouge is a fictionalized biopic of Toulouse-Lautrec, starring José Ferrer as the artist with Zsa Zsa Gabor as Jane Avril. The Hollywood Reporter's review at the time described it as, "a truly artistic production flawlessly directed by John Huston and presenting superb performances." The Academy agreed: Moulin Rouge was nominated for seven Oscars and won two, for costume design and art direction.

The most famous movie interpretation is 2001's Moulin Rouge!, which also featured one of the best last kisses in movies. Nicole Kidman played fictional courtesan Satine, who falls in love with Ewan McGregor's tragically impoverished writer Christian. Director Baz Luhrmann had been planning a musical inspired by the Orpheus myth, and after visiting the Moulin Rouge, decided that its heyday in turn-of-the-century Paris was the perfect setting for his story, according to the Guardian.

Several of the side characters were loosely based on real people. Played by Caroline O'Connor, Nini Pattes en l'Air (legs in the air) was a real Moulin Rouge dancer and the first professional dancer to teach the can-can. And the unfortunately named Chocolat, played by Deobia Oparei, is possibly a tribute to professional clown Rafael Padilla who shared the stage name. He also appeared in the 1952 movie and was one of France's first Black celebrities.