False American History Facts You Always Thought Were True

History tends to take on a life of its own over time. This leads to popular misconceptions forming in the public's mind about important people and events, particularly with early American history, and even with some events occurred during modern record-keeping. In the present day, every line a politician speaks publicly is meticulously documented and can be readily retrieved by eager fact-finders. (And nearly every line a politician speaks privately is quickly relayed by an anonymous source to a reporter, who writes up a quick summary and then starts reeling in those sweet, sweet social media clicks.)

But this was obviously not the case in the early years of the United States. It took a lot more effort to write things down and to preserve those writings. The result is authors sometimes incorrectly chronicling events in history books. With that in mind, below are a few "facts" about U.S. history that many people assume are true, but just plain aren't.

Betsy Ross designed the first American flag

American children learn in elementary school that Betsy Ross created the first U.S. flag at the behest of George Washington. Ross also allegedly made some suggestions depicted in the final design, including five-pointed stars and their circular arrangement. While it's true that Ross was a Philadelphia-based flag-maker, the notion that she designed the first flag is likely false. Her grandson, William Canby, began spreading the story almost 100 years later, in 1870, and his only evidence were testimonials from family members. Most likely, the Betsy Ross story was simply a attention-grabbing family legend that somehow made it into American history books.

If it wasn't not Betsy Ross, then, then who is responsible for the first flag's appearance? The designer was possibly Francis Hopkinson, one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence.

The Civil War ended at Appomattox

It's widely believed that the American Civil War ended when General Robert E. Lee surrendered to General Ulysses S. Grant, following the Battle of Appomattox Court House in Virginia on April 9, 1865. Lee's surrender, however, was hardly the end of the war. Several battles followed, most notably the Battle of Palmito Ranch near Brownsville, Texas that occurred more than a month later, on May 12-13, 1865. Despite news being slow in those days, both sides knew about Lee's surrender, and had even declared a ceasefire. Nevertheless, the two-day battle commenced when Union forces tried to capture Brownsville. Ultimately the Confederacy won this final land battle of the war, so they sure snagged that moral victory, at the absolute least.

American troops never invaded Russia

Thankfully, the United States and the Soviet Union never engaged in direct military conflict during the Cold War (1947-1991). Nevertheless, many Americans think that means we never actually fought Russia, and thus do not know that President Woodrow Wilson sent thousands of U.S. troops to Russia decades earlier, in September 1918. These troops were part of a larger force that comprised soldiers from the first World War's Allied countries — including the United States, France, Great Britain, and Japan. Their mission was to support Russia's White Movement, an assemblage of anti-communist Russians opposed to the Bolsheviks — forerunners of the Soviet Union's Communist Party — that had seized power during the October Revolution.

The Allies' initial goal was to beat back the Bolsheviks, and thus enable Russia to re-enter World War I against Germany. World War I ended anyway in November 1918, and by 1919 the Red Army's victory over the Whites looked certain. As a result, the bulk of the Allied forces pulled out of Russia by 1920. Ultimately, about 174 American soldiers died over those two years. The intervention may seem like a footnote in U.S. history, but it served as a prelude to future Cold War-era tensions between the Soviet Union and the West.

The Emancipation Proclamation freed slaves in the United States

President Abraham Lincoln presented the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863. Despite what is popularly believed, the proclamation did not free all slaves in the United States and did not end slavery. In fact, the proclamation only freed slaves in the Confederate states. "You're free, come on up North!" The Confederacy, of course, was in open rebellion at that time and had little interest in obeying the laws of the enemy.

The proclamation did not apply to any of the slaveholding states that remained loyal to the Union — Delaware, Kentucky, Maryland, and Missouri. The proclamation was more a goodwill gesture, a promise that the Union would end slavery if it prevailed in the Civil War. The U.S. made good on this promise several years later, when it officially ended slavery following the ratification of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution ... unless you commit a crime. Then it's back to the old ways for you.

The flag we all think was the national flag of the Confederacy, wasn't

Another commonly held misconception is that the flag of the Confederate States of America was the recognizable — and super-controversial — blue cross and red background icon displayed above. This flag was never actually the official symbol of the Confederacy. It's actually one of the Confederate battle flags, very similar to the banner that the Army of Northern Virginia (led by General Robert E. Lee) flew during conflicts. The official flag of the Confederacy changed three times during the American Civil War (1861-1865), but was never the one that everybody assumes it is. The basic "blue cross, red background" design was eventually incorporated into the official flag, but it was always only a portion of it, minimized into the upper corner.

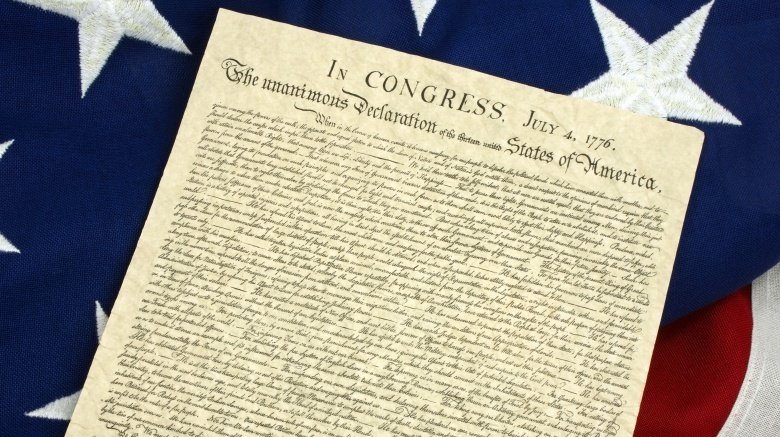

The Declaration of Independence is written on hemp paper

For the uninitiated, hemp is a type of cannabis related to marijuana. The chief difference between the two is that hemp contains very little of the chemical tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the compound in marijuana that produces the euphoric "high" effect when you smoke it. Hemp fiber has historically been used for a wide number of applications, including creating paper, so at some point, a toker likely trying to relate to a Founding Father suggested that the Declaration of Independence is written on hemp paper. You can now find numerous Internet sites that repeat this claim, but we refuse to be one of them.

It's certainly an interesting hypothesis, but we can easily prove it false by, well, looking at the document itself. Sorry, Shaggy, but the Declaration of Independence is written on parchment, which is made out of animal hide. And no, the Constitution is not written on hemp either. It's possible that Thomas Jefferson wrote some drafts of the Declaration of Independence on hemp, but even if that were true, we're not sure what that revelation's supposed to prove, except that hemp paper was more popular then than it is today.

Ben Franklin wanted the turkey to be the U.S. national bird

Another legend about one of our Founding Fathers is that Benjamin Franklin wanted the turkey, not the bald eagle, to be the United States' national bird. Franklin did question the choice of the bald eagle's placement on the Great Seal of the United States in a letter to his daughter, complaining that the eagle looked like a turkey on the seal. He then laments the choice of the bald eagle as the nation's bird, and praises the turkey's demeanor over the predatory raptor. Franklin wrote that the bald eagle is "a Bird of bad moral Character" who lazily steals food from other birds.

On the other hand, he writes the following about the turkey: "He is besides, though a little vain & silly, a Bird of Courage, and would not hesitate to attack a Grenadier of the British Guards who should presume to invade his Farm Yard with a red Coat on." It's obvious that Franklin is being facetious in this letter, employing the signature wit that made him famous. Regardless, he never explicitly states that the turkey should replace the bald eagle. Besides, as anyone suffering from a post-Thanksgiving food coma can attest, the turkey is certainly responsible for way more laziness than any eagle.

The United States won its independence because of its military tactics

A popular refrain that you hear about the American Revolution is that the colonists defeated the British forces because they used hit-and-run, guerilla-style tactics that they learned from Native Americans. As the story goes, the more regimented British military troops could not adapt to effectively fight back. The reality is much more complicated. Prior to the American Revolution, colonists actually requested help from Britain, because their military training left them inept during clashes against hostile Native American tribes. So if they brits couldn't fight back, it's not because the Minutemen were too wild and crazy. It's simply because the brits taught them too well.

It's also untrue that General George Washington was a brilliant tactician. He made several blunders during the campaign, and even lamented his own skills as an effective general. The commander of French forces, Comte de Rochambeau (pictured above), actually formulated the campaign that eventually lead to the colonists' victory over the British at the Siege of Yorktown. The surrender of Lieutenant General Charles Cornwallis of England in 1781, at Yorktown, effectively ended the war. That being said, the real motivation for Great Britain giving up the fight wasn't that they were beaten beyond all hope, but rather the onerous financial cost of the war, combined with waning popular support.

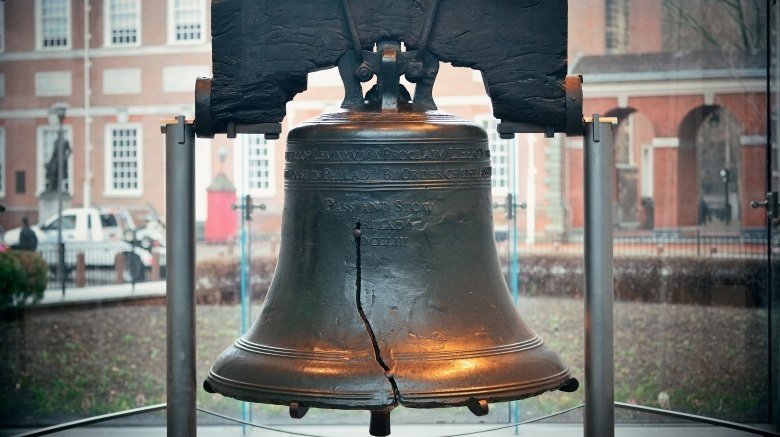

The Liberty Bell cracked on July 4, 1776

Several popular misconceptions exist about the Liberty Bell. First, no one called it the Liberty Bell during the American Revolution. The bell was initially known as the State House Bell and, appropriately enough, resided in the Pennsylvania State House. People didn't begin referring to it as the Liberty Bell until abolitionists labelled it as such during the 1800s.

Second, the notion that the bell cracked after being enthusiastically rung by patriots on July 4, 1776, is pure bunk. Actually it probably didn't ring at all on that famous day, mainly because the bell began to crack years earlier, starting in 1752, and required constant maintenance during its run in the Pennsylvania State House. The crack that you see today when visiting the bell in Philadelphia likely occurred in the 1840s. In short, the Liberty Bell was the equivalent of that car that you need to constantly throw money at to keep working. Nevertheless, it's still an important national symbol to this day.

Reagan freed the Iran Hostages

There's a persistent myth about President Ronald Reagan's foreign policy legacy that you've likely heard during recent political discussions. According to some, the Iran hostage crisis only ended because of Reagan's election. The story goes that Iran had no respect for Reagan's predecessor, President Jimmy Carter, but submitted and released the hostages in the face of a more powerful opponent like Reagan.

Thing is, this tale is a simplistic misunderstanding of what actually occurred. Reagan had nothing to do with the negotiations to release the hostages, but still received a lion's share of the credit for it. The Carter Administration had begun negotiating with Iran months earlier, in September 1980. But the Iranian government strongly disliked Jimmy Carter for providing aid to the Shah of Iran — the country's former monarch — and for a failed attempt to rescue the hostages months earlier. So while it's true that Iran did not release the hostages until President Reagan's inauguration day on January 20, 1981, its decision to do so had less to do with Reagan, and more with embarrassing President Carter.

Support for leaving the Union was uniform across the Confederacy

Although 11 Southern states broke away from the U.S. to form the Confederate States of America, it would be a mistake to think everyone in these states supported secession. The reason that West Virginia even exists today is because its residents chose to break away from Virginia rather than follow it into the Confederacy.

Tennessee almost broke up too — almost 70 percent of voters in eastern Tennessee voted against seceding from the U.S. on June 8, 1861. After losing the vote, several counties in eastern Tennessee petitioned the state government in Nashville to allow the region to remain in the United States, but the Tennessee government rejected the request. In fact, Confederate troops had to occupy parts of both east Tennessee and northern Alabama to prevent rebellion.

There were several other pockets of Unionist support in the Confederacy, too. These were mostly areas where the majority-white population owned few slaves and saw no real reason to fight to keep them. Another notable example is Jones County, Mississippi, that formed the basis of the 2016 film Free State of Jones.

The Siege of Yorktown ended the American Revolutionary War

We learned in American history class that the nascent United States won the Revolutionary War after American and French forces — commanded by generals George Washington and Jean-Baptiste de Rochambeau — defeated the British at Yorktown on October 19, 1781. While this defeat effectively dashed the British's hope of quelling the colonial rebellion, it was hardly the final battle of the war. Instead, the last skirmish was the naval Battle of Cuddalore in the Bay of Bengal, off the coast of India, on June 20, 1783. That's right, the final battle of the American Revolution took place in coastal India, eighteen months after the whole thing was supposed to end.

How is that even possible? Well, recall that France sided with with the United States in 1778. Once it did so, France was also at war with Great Britain. The conflict between the British and the French was not restricted to the colonial U.S., and instead took place on a global scale. Ironically, the battle occurred as the United States (led by dignitaries Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson), Great Britain, and France were negotiating the formal end of hostilities in Paris. Ultimately the French prevailed in the Battle of Cuddalore. Vive la France!

Washington D.C. has always been the capital of the U.S.

All Americans know Washington D.C. is the capital of America, but what they might not know is D.C. is actually our ninth capital city. The first capital was Philadelphia, where the Continental Congress convened in 1774 and signed the Declaration of Independence two years later. The the capital changed several times during the Revolutionary War — from Philadelphia to Baltimore to even Lancaster, Pennsylvania — as Congress constantly moved to keep one step ahead of the British Army.

In 1789, George Washington actually took the oath of office as the first president of the United States in New York City, meaning Federal Hall in the Big Apple briefly served as the first capital of the United States (under the U.S. Constitution) from 1789-1790. Philadelphia then became capital again, until the District of Columbia could be completed.

The Civil War was fought over state's rights

There is a lot of misinformation in the zeitgeist about the American Civil War. Most prominently, Americans seem confused about the cause of the war itself. A 2011 survey by the Pew Research Center found that 48 percent of Americans thought the war was caused by a battle over states' rights, and 38 percent thought it was because of slavery. It can't be both ... right?

Well, if you peruse the most direct source possible, the Confederate states' justifications for secession, it becomes abundantly clear that their primary reason for leaving the U.S. was indeed the preservation of slavery. "The new [Confederate] constitution has put at rest, forever, all the agitating questions relating to our peculiar institution African slavery as it exists amongst us the proper status of the negro in our form of civilization. This was the immediate cause of the late rupture and present revolution," said Alexander Stephens on March 21, 1861. Almost one year later he would become the first and only vice president of the Confederate States of America.

"Confederate states did claim the right to secede, but no state claimed to be seceding for that right. In fact, Confederates opposed states' rights — that is, the right of Northern states not to support slavery," wrote historian James W. Loewen in a Washington Post article on the issue. Then the Confederates attacked Fort Sumter and the war was on. Making things more confusing is the fact that Lincoln was strongly against slavery but initially argued that the war would be about keeping the Union together because he knew many in the North and on the border didn't care enough about slavery to go to war about it. Less than two years into the war, he signed the Emancipation Proclamation in an attempt to make it crystal clear for future armchair historians what was at stake.

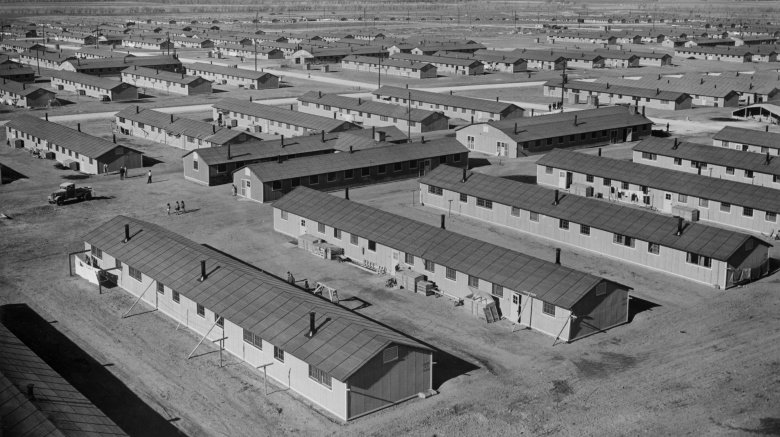

Only Japanese-Americans were interned during World War II

One of the darkest pages in U.S. history was Executive Order 9066, the decision by President Franklin Roosevelt to forcibly intern approximately 110,000 Japanese-Americans in camps during World War II. The U.S. government was fearful of espionage from the Japanese-American community after the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941. This fear caused the government to grossly violate the civil rights of thousands, by forcibly relocating them to ten internment camps primarily scattered throughout the western United States. The U.S. government didn't apologize until decades later, when President Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988.

Yet, many don't realize that Japanese-Americans weren't the only group who were licked up in such camps. In addition to more than 11,000 German residents of the U.S., several thousand Japanese-Latin Americans were also sent to these camps. Peru, in particular, has a significant Japanese minority. Many Japanese-Peruvians descended from Japanese immigrants traveled to Peru in the 19th century, looking for work. By the time World War II rolled around, and the U.S. asked for Latin-American countries to arrest their Japanese populations, the Japanese-Peruvian population stood at about 25,000. This, combined with resentment toward the generally prosperous Japanese minority, was all the justification that some xenophobic elements of Peruvian society needed to deport their fellow countrymen to the U.S., and to those wretched camps

World War II never made it to the U.S. mainland

Americans, for the most part, assume that World War II never reached the United States mainland. Sure, we all know about Pearl Harbor, and some of us are even familiar with the Battle of the Aleutian Islands between the U.S. and the Japanese (June 1942 to August 1943). Yet neither Alaska or Hawaii are part of the mainland, nor were they even states at the time.

Yet, unbeknownst to some, the Japanese did attack the U.S. mainland several times during the war. In fact, it would seem that before hipsters, the greatest threat to our west coast was the Japanese military. For one, a Japanese submarine shelled the Ellwood Oil Field near Santa Barbara, California on February 23, 1942, and a few months later, on June 24, 1942, a different Japanese submarine opened fire on Fort Stevens in Oregon. In September 1942, on two occasions, the same submarine used a floatplane to drop incendiary bombs near Brookings, Oregon in hopes of starting a forest fire. Fortunately, none of these attacks caused major damage, but that doesn't mean they didn't happen.

The Pilgrims were escaping religious persecution

As youths, many of us learn that the Pilgrims immigrated to the New World and founded a colony in Plymouth, Massachusetts in 1620, in order to escape the religious persecution they faced in England. This is all accurate, except for the bit about religious persecution. Religious intolerance was actually not a huge factor in the Pilgrims' decision to venture to North America. The Pilgrims, in fact, had already found the religious tolerance they sought in Holland.

So why leave that wonderland? What was the problem? They loaded up the Mayflower and crossed the Atlantic for two reasons: to maintain their English identity, and to pursue better economic opportunities. Also, the Pilgrims envisioned that someday, their likenesses would make adorable salt-and-pepper shakers — but that's just our theory.

The Salem Witch Trials featured burnings galore

The Salem Witch Trials, which lasted from February 1692 to May 1693, is one of the most prominent examples of mass hysteria in American history. During this period, hundreds of people in Salem Village, Massachusetts were accused of witchcraft, and about twenty people were executed.

You popularly hear that the puritanical government burned these poor "witches" at the stake. This is, shockingly, yet another myth. Although witches were burned at the stake in medieval Europe, almost all the "witches" in Salem were hung. After all, firewood isn't cheap, folks, and Massachusetts gets cold! Just ask anyone who lives there. They'll tell you. Repeatedly, and loudly.

The only "witch" to escape hanging was Giles Corey, who had the distinct displeasure of being pressed to death with heavy rocks. Some people will do just about anything to get out of church.