The Wild History Of The Summer Of Love Explained

Imagine a time when the world seems to be swept up in a spirit of optimism and joy — the sense, perhaps, that everything is moving in the right direction, and the concepts of freedom and love are at the forefront of people's minds. It feels like such a phenomenon would be impossible now, but in the US just over 50 years ago, a change was in the air, so much so that the summer months came to be given a title which has stuck ever since.

In 1967, around 100,000 hippies descended upon the Haight-Ashbury area of San Francisco. There, they took drugs, performed and listened to psychedelic music, engaged in nonconformist political activism, and practiced "free love." The phenomenon was given a name: "The Summer of Love."

But what was the Summer of Love, apart from this shared feeling among America's youth? And how did it come about? Was it really all that we're making it out to be, or was it in fact just an excuse for kids to turn to debauchery and hedonism? Did the Summer of Love really mean anything at all?

All of these questions are still up for debate, but the fact that the summer of 1967 stands for many as the apotheosis of something means it is worth revisiting and could, indeed, tell us much about exactly where we are today.

San Francisco 1967: the crest of the wave

There are many factors that play into 1967 becoming the Summer of Love and for San Francisco becoming its center. What's important to note, perhaps, is that those summer months, and what occurred in Haight-Ashbury in particular, did not exist in a vacuum. Rather, the Summer of Love stands as the high point of decades of countercultural activity in the US and beyond. The values and ideas of the hippie movement had been active and growing for a long time by 1967 — it was just that in this year, the whole culture seemed to spill over into the mainstream and, according to The Guardian, dominate the media around the world.

The feeling of change to those who experienced it was, apparently, palpable. The journalist Hunter S. Thompson, who was active in San Francisco at the time, recalls in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas the feeling that he was "riding the crest of a high and beautiful wave," that the West Coast in the mid-'60s, in his memory at least, represented "the high-water mark — that place where the wave finally broke and rolled back."

The concept of the countercultural "wave" is a very useful one, which tells us that the Summer of Love was already building before 1967, and its effect was felt thereafter, though with less intensity. However, San Francisco was always at the center of the action.

The old guard: Beats turn hippie

Part of the draw of San Francisco to the hippie movement was the presence there in the preceding decades of the writers and thinkers whose works formed the foundation of 1960s counterculture. Most notably, the Beat Generation, who had risen to prominence in the 1950s, had a strong affinity to and presence within the city. Vanity Fair notes that San Francisco's North Beach, and in particular the City Lights bookstore, was a famous hotspot for the Beats.

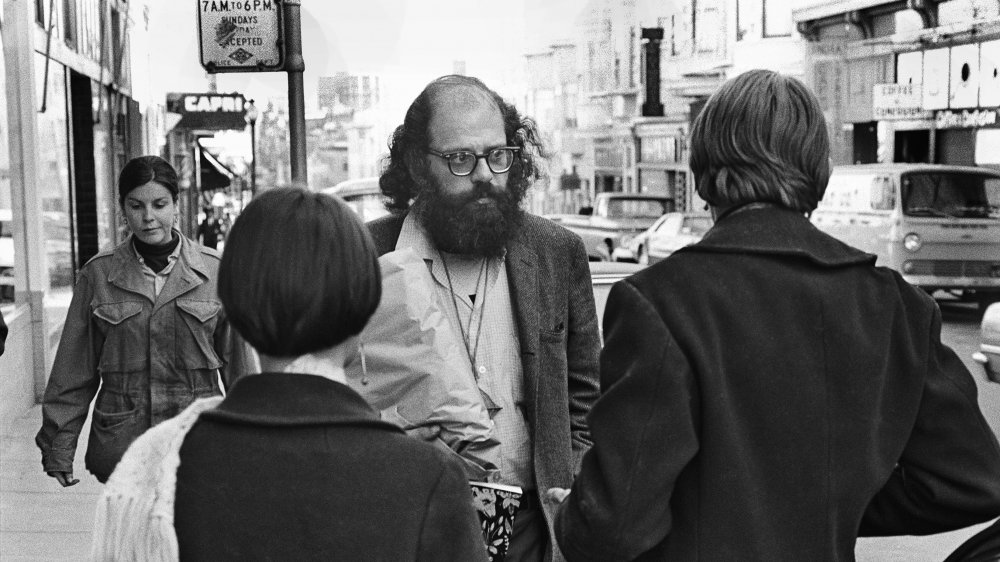

Jack Kerouac's On The Road (1957) and Allen Ginsberg's long poem "Howl" (1956) became central texts in '60s counterculture, promoting nonconformism, freewheeling travel and rootlessness, and an appreciation for passionate and intense experiences. Bob Dylan remarked: "I read On The Road in maybe 1959. It changed my life like it changed everyone else's."

Though Kerouac himself would later disavow the growing hippie movement of the mid-'60s, Ginsberg became one of its most central proponents, activists, and speakers, performed at the "Human Be-In" (the event that many now consider the starting point of the Summer of Love), and continued to be a vital presence throughout 1967. Neal Cassady — on whom On The Road's Dean Moriarty character is based — was also present during the Summer of Love, as the driver of a van of traveling LSD-dispersing hippies named the "Merry Pranksters."

It begins: the Human Be-In

Those who were a part of the growing hippie movement of the mid-'60s were easy for non-hippies to identify, visually at least. But the interests and political beliefs of those who were drawn to the lifestyle were hard to pin down. Though hippies were generally anti-conformist, anti-consumerist, and anti-establishment, there was no common goal for this new breed of young American.

An event at Golden Gate Park in January 1967 aimed to change all that. Titled the "Human Be-In," it attracted more than 30,000 young hippies, according to The Nation, more than five times the number of participants at counterculture gatherings that had happened before. Suddenly, it seemed, everyone identified as hippies. The Human Be-In was an attempt to help hippies work together to shape the world in their image.

Subtitled "A Gathering of the Tribes," the Human Be-In brought together disparate threads of the counterculture to affect political change. The gathering was in part a protest against the illegalization of the new psychedelic drug LSD, which had been banned in California in 1966, and also created a forum for the intermingling of anti-war activists and pacifists of many stripes. Meanwhile, the spiritual and mystic aspects of the hippie movement were brought together, with Allen Ginsberg leading the gathering in a communal om ceremony.

The bands performing would provide the soundtrack for the Summer of Love, such as the Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane.

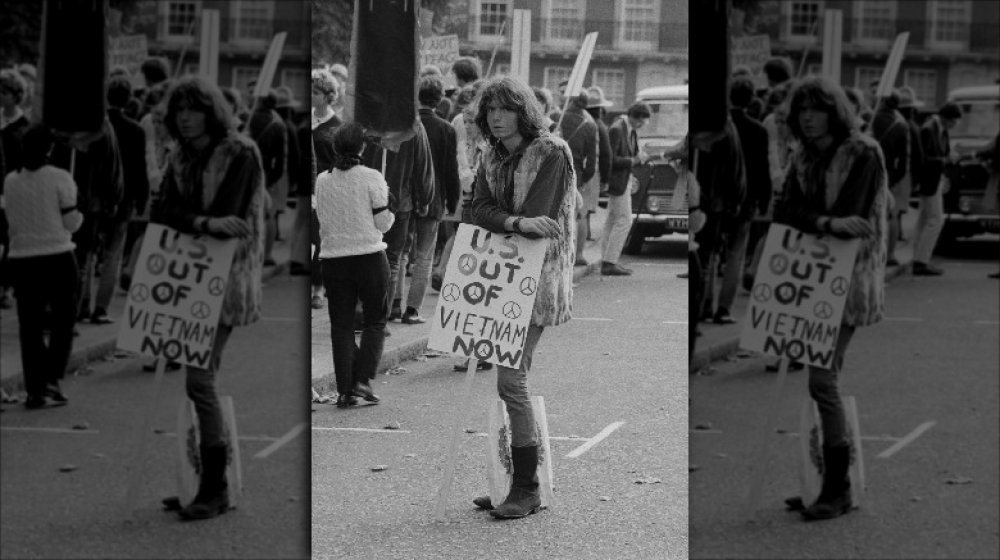

The Summer of Love and the Vietnam War

If we are to think, as Hunter S. Thompson did, of the counterculture of the 1960s as a wave, then it lapped against some of the major issues of the decade. The Vietnam War was a key catalyst in changing the way that young people viewed society and their place in it. According to Charles A. Reich's 1970 book The Greening of America, "it forced a major breach in consciousness. And it made a gap in belief so large that through it people could begin to question all the other myths of the corporate state." As a result, hippies were a conspicuous presence at anti-war protests throughout the late '60s.

Allen Ginsberg had spoken at anti-war protests in Berkley, and his appearance at the Human Be-In was similar in nature, an attempt by the organizers to bring the "anti-war, activist hippies and the psychedelic hippies" together.

The common goal among young men especially was to resist the Vietnam draft. David Harris, a central figure in the draft resistance movement, said: "A lot of hippies at the time were looking to get stoned and dance and play. We were all for getting stoned and dancing and playing, but the serious business was how to deal with the machine that's chewing up Southeast Asia. All those things were mingled together and they were all part of the same uprising of young people who insisted on writing their own ticket."

The Summer of Love and LSD

Drugs became a central component of the '60s counterculture, not simply as recreation but as a politically motivated and culturally subversive act that expressed the attitudes of its many disparate but intertwining youth movements against the status quo.

According to Vanity Fair, lysergic acid diethylamide, or LSD, had been developed more than a decade before the Summer of Love by Sandoz Laboratories, the synthesis of the natural psychedelics psilocybin, which is found in magic mushrooms, and mescaline. The drug played a major role in creating the atmosphere of togetherness at events such as the Human Be-In, for which the local psychedelics dealer Owsley Stanley was convinced by the Diggers to donate thousands of doses to the crowd, according to The Nation.

"For the LSD era there was something mythic about this initiation," writes Eric Rothstein. "Epic heroes have always descended into the underworld to emerge, however scarred, bearing new forms of wisdom. That was also the LSD archetype: descend into madness and emerge enlightened, seeing the world anew." The goal was enlightenment: "With LSD, we experienced what it took Tibetan monks 20 years to obtain," one member of the Family Dog commune told The Week, "yet we got there in 20 minutes."

The high priests of psychedelia: Timothy Leary and Ken Kesey

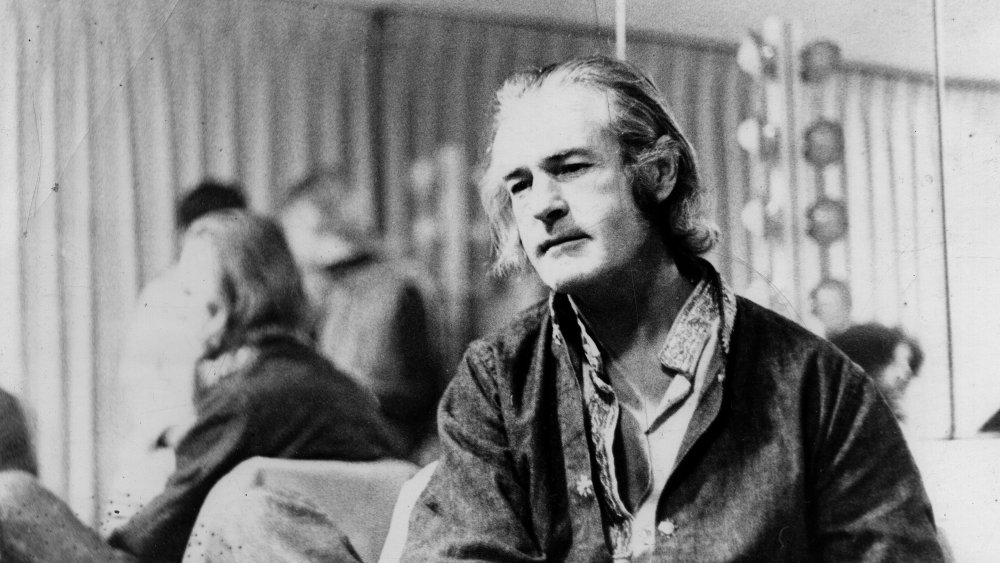

Two elder figures of the hippie movement were instrumental in spreading word of the mind-expanding capabilities of LSD, both of whom had experiences with the drug while it was still undergoing medical trials within academic and medical institutions.

According to Vanity Fair, Ken Kesey had volunteered in 1959 to be a participant in an LSD experiment at the VA hospital in Menlo Park, a trial that was overseen by the CIA. The experience would inform his famous novel, 1962's One Flew Over The Cuckoo's Nest. It was Kesey who formed the Merry Pranksters, whose painted bus traveled the length and breadth of America conducting "acid tests," which introduced a generation of young people to the effects of psychedelics.

Timothy Leary (pictured above) was a similarly influential figure. Leary was a psychologist who had experimented with psilocybin at Harvard in the 1950s and, according to The Week, came to believe that LSD was key to helping humans understand the true nature of the universe. At the Human Be-In, Leary addressed the crowd and uttered the phrase: "Turn on, tune in, drop out." It became a mantra for the hippie movement, though critics of the '60s counterculture pounced on the phrase as evidence of the movement's inherent hedonism and shallowness.

Richard Nixon later described Leary as "the most dangerous man in America."

The pill and "free love"

The spreading of spiritual love aided by the availability of LSD also had its physical counterpart. "Free love" — the ready engagement in premarital sex which had been such a taboo in previous decades, as well as sexual experimentation which occurred within the communes and communities of the hippie movement — was given a boost by the growing availability of the contraceptive pill.

Greater openness around sexual behavior among the hippies occurred as part of the greater "sexual revolution" which had been gathering steam throughout the '60s, but this aspect of the movement also became one of the greatest battlegrounds in the culture war between the progressive youth and social conservatives, whose knee-jerk reaction was to brand free love immoral.

PBS' American Experience notes how the pill itself was scapegoated by conservatives who were worried by the separation of sex from the act of procreation. The double standard by which women were judged can be seen plainly in retrospect: While it was accepted that bachelors might engage in premarital sex with little moral judgment, the same behavior in women attracted scorn from conservative commentators. The movement was self-consciously aware of the subversive role that free love played. Peter Coyote of the Diggers claimed: "I was interested in two things: overthrowing the government and f*cking. They went together seamlessly."

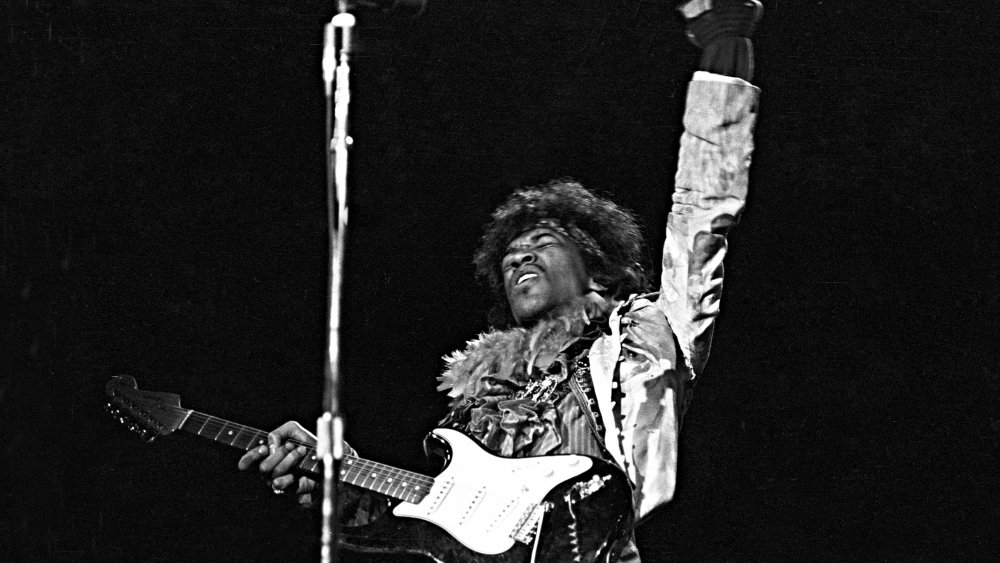

The climax: the Monterey International Pop Festival

The centerpiece of the Summer of Love occurred June 16-18, 1967, in what uDiscoverMusic describes as "the first major rock festival in America." The Monterey Pop Festival attracted some 200,000 people of the course of the weekend, having been organized by key figures in the countercultural music scene, including John Philips of the Mamas and the Papas, former Beatles publicist Derek Taylor, and record producer Lou Adler.

The festival gained worldwide attention weeks before it opened thanks to the release of "San Francisco (Be Sure To Wear Flowers In Your Hair)," a song written by Phillips and performed by Scott Mackenzie. The song, released especially to promote the festival, became a worldwide hit and is said to be partially responsible for drawing so many young people to Haight-Ashbury and the Monterey Pop Festival in particular.

The press coverage of San Francisco in the months preceding the festival meant that Monterey became a worldwide media event, and images from the festival — many coming from the 1968 documentary on the event made by D.A. Pennebaker — have become icons of the hippie movement. The festival showcased the most famous acid rock bands of the decade but also made the names of many of them. Jimi Hendrix, Otis Redding, and The Who all came to prominence after their performances that weekend.

The end of the Summer of Love

On October 6, 1967, after thousands of young subversives streamed into San Francisco and basked in the glow of the Summer of Love, the season was brought to a semi-official close by members of the Diggers, whose objective, according to the University of California Santa Cruz, was to convince the world's media to stop covering the Haight-Ashbury scene and for rootless hippies to "bring the revolution to where you live."

The end was signaled by a ceremony titled "The Death of the Hippie," a mock funeral undertaken in the streets of Haight-Ashbury in which the participants burned hippie clothing and underground art and magazines and carried a symbolic coffin through the neighborhood. A funeral notice declared: "Funeral Notice: HIPPIE. In the Haight Ashbury District of this city. Hippie, devoted son of Mass Media. Friends are invited to attend service beginning at sunrise, October 6, 1967 at Buena Vista Park."

The Diggers were aware of how the movement was being co-opted by the mainstream and commodified as a lifestyle. The event, therefore, was an attempt by the group to detribalize the moment and disperse its subversive energy into more areas of American life. Many hippies did indeed return home or go off to college in the fall of 1967. DW describes this time as the Summer of Love's "faded dream," the point at which the intensity of the summer months became unsustainable.

The hippie attitude and legacy

The Diggers were right to be concerned about the lasting legacy of the summer of love and how the message of the '60s counterculture was being assimilated into the mainstream. The Spectator describes how, in the aftermath, the summer months seemed like "a fever-dream," while Haight-Ashbury became populated by a great number of addicts and charlatans trying to make an easy buck.

Looking back now, it seems that the hippie as an identity or tribe of people is close to dead in the 21st century. However, the sexual freedoms pioneered during the 1960s have taken hold in a great number of countries around the world. On the other hand, the United States' War on Drugs became a long-running policy error, and social conservatism is anything but a thing of the past. In the years immediately following the Summer of Love, however, traces of the counterculture seeped into politics at every level. Hunter S. Thompson famously fought the "Battle of Aspen" in 1970, running for sheriff of the town on a "Freak Power" ticket.

Thompson lost, but another follower of the hippie movement did rise to political prominence: Jimmy Carter, who, in a 1974 speech, declared, "The other source of my understanding about what's right and wrong in this society is from a friend of mine, a poet named Bob Dylan. After listening to his records [...] I've learned to appreciate the dynamism of change in a modern society."

The second Summer of Love

Though San Francisco was the epicenter of the counterculture of the 1960s, the hippie movement was sprouting up around the globe. New York was another hive of subversive activity, and there was also a youth-led social revolution occurring in the UK, especially in London. More than 20 years later, the British Isles would witness yet another phenomenon centering around love, music, sex, and drugs. The year was 1988, and this time, it was the British rave scene and a new drug — ecstasy — which would bring young people together.

Recalling the "acid rock" genre of the 1960s, "acid house" was the soundtrack to a club scene that many felt had parallels with '60s counterculture. And again, it was self-aware, as Sharon Walker writes in The Guardian: "As a Mexican wave of parties swept through London in a rush of joy and unity, a new world emerged from the swirl of dry ice and pulsing beats, one that was to shape our culture and outlook for the next generation."

Beats were interlaced with speeches by figures such as Martin Luther King, while the Day-Glo style which came to permeate the scene provided a neon update of the flower power movement.

Will there be another Summer of Love?

If this article has given you a sense of nostalgia, you're not alone. For many, the promise of a Summer of Love happening again is tantalizing. Thirty years on from the acid house boom of 1988, Mixmag asked, "Will there ever be another Summer of Love?" In 2017, event organizers in Amsterdam latched onto the 50th anniversary of the first Summer of Love to declare that the "Third Summer of Love" was underway, though it can't be said that this has particularly entered popular consciousness. More recently, UKF has described the spate of illegal raves that have occurred throughout the UK during the coronavirus pandemic as a potential equivalent of a third Summer of Love, but perhaps it would be more fitting to describe these gatherings as having arisen through cabin fever, rather than love and mind expansion.

The plausibility of a third Summer of Love occurring in our lifetimes depends upon how one views societal change and the passage of time. If you were to consider the 21st century as having progressed — or, depending on your point of view, degenerated — past a certain point, then it would appear that a genuine countercultural moment on such a scale might never happen again. However, some of the largest social movements that have emerged in the last decade — #MeToo, Black Lives Matter, and Fridays for Future — should give us pause for thought. Another wave, perhaps, is possible.