The Strangest Status Symbols Throughout History

Creatures of all kinds are obsessed with status and hierarchy, from mankind to across the animal kingdom. It's no secret that humanity has managed to organize itself into a class system, and animals do the same thing. A herd of horses, for example, will have an alpha mare who's dominant over her companions (via Rutgers), and even a flock of chickens will arrange itself into a strict social hierarchy. For real: a Norwegian zoologist coined the term "pecking order" in 1904, and Your Chickens says the pecking is a very real reminder of who's in charge.

Humans have (mostly) moved beyond pecking, kicking, and nipping to exert their dominance, so how are we supposed to know at a glance who's in charge? By the display of status symbols, of course! And money? That's for amateurs.

It was a long time ago that humans discovered they could wave something special, unique, or expensive in the faces of others, and those others would sit up and take notice. More importantly, they'd be impressed. And people have been impressed by a lot of weird stuff over the years.

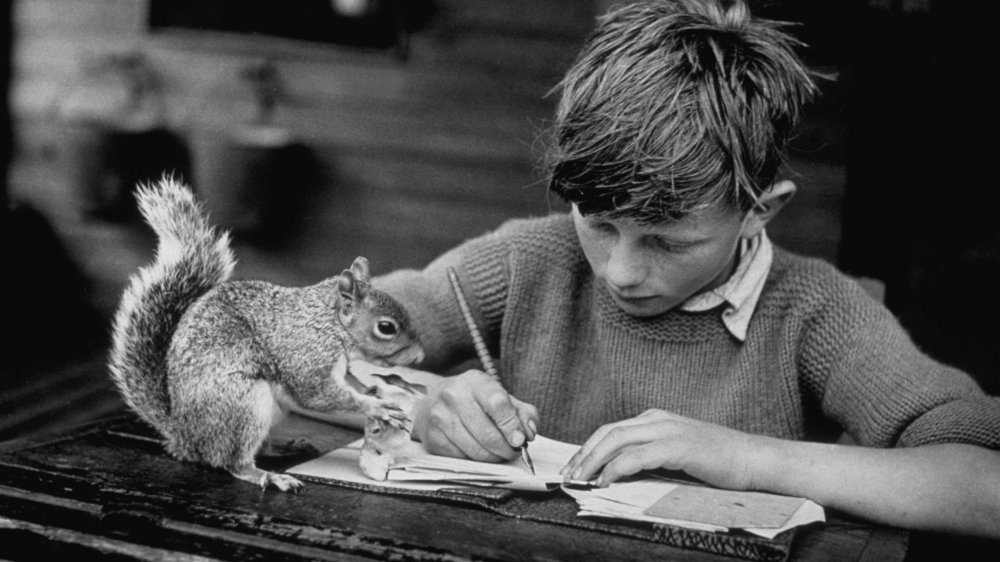

Squirrels: The trendiest pet of the 18th and 19th centuries

Squirrel mania gripped the upper classes by the 1700s, and all those paintings of upper-class children and their pet squirrels are absolutely depicting the real thing. Most were American Grey Squirrels, says Atlas Obscura, but there were other types, too — and they remained a popular pet across the country for centuries. Books about domestic pets notably included descriptions of and instructions for caring for your squirrel, pet shops sold them to those who couldn't be bothered with plucking one from its nest in the wild, and even Benjamin Franklin wrote an ode to a friend's pet squirrel after it had a tragic and fatal incident with a dog.

Even though the idea of having a pet squirrel running around your house, hiding nuts and sugar cubes in all the little nooks and crannies it can find while causing some seriously adorable chaos is pretty cool, there was a down side. They were such popular pets that even at the time, people were concerned that the pet squirrel trade would push them to the brink of extinction in the wild.

They didn't need to fear: squirrels slowly made the transition from treasured pet to annoying pest, partially because people started to realize you can't really train a squirrel. By the 20th century, they were fully in the "annoyance" category, and laws regarding wildlife conservation and keeping wild ones as pets put an end to these bushy-tailed companions.

How much would you pay for a tulip bulb?

Tulips are definitely pretty, and some of the more unique varieties are downright gorgeous. But how much would you pay for one of them? Would you hand over the price of a nice house? Or how about a year's salary?

Between December 1636 and February 1637, tulip prices hit an all-time high. Historian and King's College London professor Anne Goldgar has done a huge amount of research on the tulip phenomenon of the 17th century and found (via History) that during those months, some of the rarest bulbs were going for the price of a very nice house, or the year's salary of a skilled craftsman. It's not surprising, then, that she also found that buyers were among the most successful artisans and the richest merchants. Tulips were a luxury.

And here's the strangest thing: according to the BBC, some of the most oft-told tales of tulip mania were terribly exaggerated. It's been repeated over and over that the collapse of the tulip market was a major financial crash, but it wasn't. That kind of takes away from the truth: that the wealthy Dutch merchant class loved collecting and showing off their rare tulips, and paid an ungodly amount of money to do so.

Pineapples: It's not even pre-sliced!

Pineapples made their way to Europe with Christopher Columbus, and it wasn't long before Europeans realized that a) they were awesome, and b) they just didn't have the climates to grow them. Unless, that is, they were grown in one of a handful of hothouses in the Netherlands and England. That, says Mental Floss, led to a simple case of supply and demand. Supply was low, demand was high, and that meant growers could charge insane prices. How insane? The American colonies were able to import pineapples from the nearby Caribbean, but they were still pricey: one could cost the equivalent of around $8,000 in today's money.

Many times, these pineapples weren't even eaten, because by the time they got where they were going, they were pretty rotten. They were put on display as decorations instead, and they were proof of just how much money someone had to spend on either buying a rotten pineapple, or renting one for the evening, because pineapple rentals were a thing, too. They were such a huge deal that Charles II even commissioned a painting of himself receiving a pineapple from his gardener!

Gradually, pineapples came to symbolize hospitality, which is why there are so many images of pineapples in olde-timey household items. The whole fad fell out of fashion in the early 1900s with the establishment of the Hawaiian Pineapple Company, which we now know as Dole.

Early body modifications, for status's sake

Body modification, it turns out, is nothing new. The BBC says that molding the skulls of babies into particular — and unnatural — shapes has been done since around 45,000 years ago, and sometimes, it was done to show off the status of the child and his or her family.

Archaeologist Mercedes Okumura, of Brazil's National Museum, says that not only were differently-shaped skulls often considered beautiful, but that "There is strong evidence that physical manipulation of skulls was undertaken not just to reinforce social distinction, but also to entrench political power." Take Bolivia's Oruro people. Okumura says that the upper class had "tabular erect heads," the middle class went with "tabular oblique heads," and everyone else went with an appropriately ordinary "ring-shaped" head.

Head-shaping is seen in a lot of cultures, and it's worth a disclaimer to say that it's not always about status. But for some, it is: in pre-Columbian America, it was a widespread practice among the elite. And among the Cowlitz and Chinook tribes during the 19th century, deliberately flattened foreheads were seen as "a mark of freedom," while those with unshaped foreheads were scorned (via the BBC).

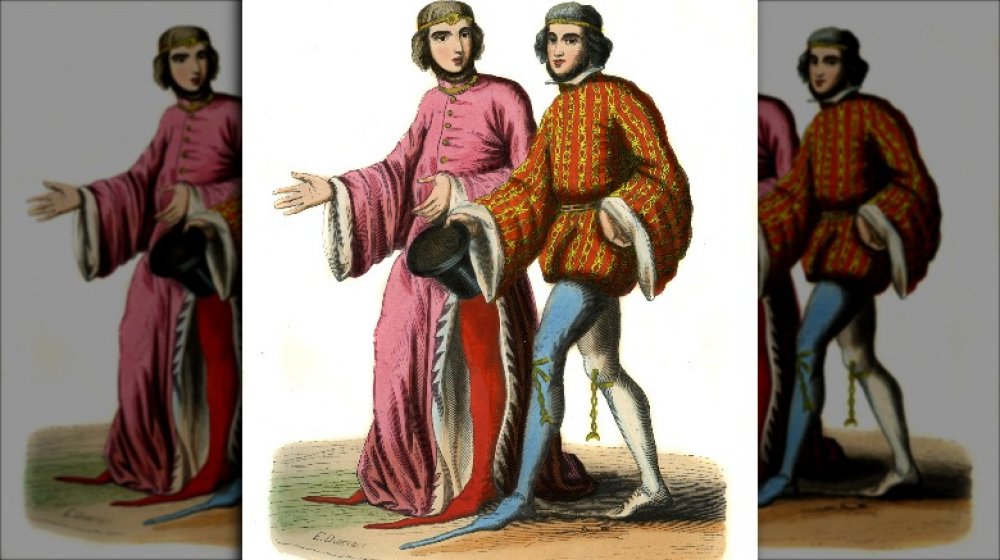

They're not exactly Air Jordans

Around 1340, something strange came out of Krakow: a new type of shoe with a ridiculously long toe that came to a point. They were called crakows or sometimes poulaines, and sometimes it was just the tips of the shoes that earned that second name.

They absolutely look like something that would be added into the costumes of a medieval screwball comedy by Mel Brooks, but they were very real and those toes were so long that medieval shoemakers weren't just making them, they were stuffing them to keep them rigid. Rebecca Shawcross of the Northampton Museum and Art Gallery says (via Atlas Obscura) that the general idea was that if a person could wear these ridiculous shoes, they clearly had enough money that they didn't have to worry about practical footwear suited to a life of physical labor.

Gradually, the shoes started to take on another connotation, and it was widely whispered that the longer the toe, the more "masculine" the wearer... wink, wink, nudge, nudge. Shawcross says that's when English lawmakers stepped in to put restrictions on just how long the toes of shoes could be. It was just a matter of decency at that point, and by 1475, this status symbol had fallen by the wayside.

Got too much cash? Build a completely pointless building

Fun fact: there's plenty of people who have felt it necessary to flaunt their wealth and status by building something that's pretty pointless. They're called follies, and The Folly Fellowship says that defining what they are is tough. Generally, they're a "building made primarily to be seen," and there's a lot of wiggle room in there. Follies range from two-dimensional arches and "towers" to belvederes (buildings constructed with a viewpoint at the top and nothing else), and similarly, dry bridges. Those are what they sound like: bridges over land, often built just to stand on and look at something.

There's also the cottage orné , which is essentially an unnecessarily decorative building modeled after a quaint sort of olde-timey cottage. It's often stone or thatched, sometimes it's a chicken coop, and sometimes it's built for the lady of the house. Why? So she can "play at being rural without actually getting dirty." Nothing says status quite like that. There are also fake medieval ruins, grottoes, towers, obelisks, pyramids, rotundas, random sculptures... there were even tortoiseries, which were houses for tortoises.

Even though the buildings themselves serve no real or important purpose, Amusing Planet says there was often a point to their actual construction. In times when jobs were scarce, and food was even scarcer, rich landowners would hire locals to build follies. That way, no one was providing or accepting charity, they were simply getting paid for an honest day's work.

Personal hermits: One more mouth to feed

Ever wish you could retire to the quiet life, and just go live in a little house somewhere in the English countryside? It's too bad that it's not the 18th century anymore, because thanks to wealthy landowners who wanted to show just how wealthy they were, there were plenty of job opportunities doing exactly that.

Gordon Campbell, a University of Leicester professor of Renaissance Studies, says (via Atlas Obscura) that it was a weird thing. Hermits were often hired from an estate's agricultural workers, and were sometimes told to dress like a druid... but since no one was entirely sure how druids actually dressed, they usually just ended up putting on a funny hat and calling it a day.

This 18th century hermitting was rooted in old-school hermits that did it for spiritual reasons, but the practice we're talking about was decidedly less spiritual and probably less fun than it sounds. Job advertisements for hermits often specified a time period when the hermit was forbidden from speaking to anyone, and also wasn't allowed to bathe or trim their hair and nails, to maintain that proper "druidic" appearance. On the other hand, other lords required their hermits to entertain guests to the estate, read and write poetry, and almost always embody the spirit of the melancholy, which was super trendy at the time.

Sugar: For more than just a sweet tooth

Sugar is everywhere these days, and while it's undeniable that we still treasure it, we're not exactly showing off our Coca-Cola and Mars bars as a status symbol. Back in Elizabethan England, though, sugar was quite the thing to have. Banquets have long been a way for the rich to show off their wealth to, well, mainly other rich people. The medieval period was filled with banquets where the centerpieces were things like live birds that flew out of pies, and when trade between the New and Old World made sugar a little more widely available, those centerpieces became massive monuments to confectionery creativity.

According to The Getty, chefs would make a long-lasting mix of sugar and edible sap called gum arabic. That was called pastillage, and chefs would then construct table-sized dioramas, small-scale landscapes, and even monuments as tall as a person. Some — like Pope Innocent XI — were known to assign guards to protect the creations, while other times, pieces of the sculptures would be passed out to guests. The ones pictured were from a dinner in Rome, given by the British ambassador in 1687.

They weren't just edible sculptures, though, they were art. The British Museum says that a person's ability not only to buy the sugar but to hire the number of skills chefs it took to create these labor-intensive masterpieces was what was really on display, and at least it was a tasty way to show off.

Getting the rich man's disease

It was so associated with wealth and status that it was called "the disease of kings" and "the rich man's disease." It was gout, which Drawing Blood says is a form of arthritis we now know is associated with too much uric acid in the bloodstream.

And here's where we come to the status symbol part of it. In the 19th century, gout was thought to be caused by an overindulgence of the sort of things that only the wealthy could afford. That was things like alcohol — particularly alcohols like port and claret — along with a diet rich in meat and seafood. To clarify? The pain of gout is crippling, but it was a desirable thing to have because it didn't just mean you could afford the best of the best, it meant that you could afford a lot of it.

Illustrations of those suffering from gout were less kind, and many showed them as gluttons who were paying the price for their indulgences. Still, there were comments like this one in the London Times in 1900: "The common cold is well named — but the gout seems instantly to raise the patient's social status." Gout, says a historical piece in the journal Arthritis Research & Therapy, was "socially desirable."

They're going to outgrow those in no time

Shoes have always been a big deal, from Air Jordans to those funny ones with the red soles. It kind of makes sense that adults want to show off their shoes, but in Ancient Rome, they were doing something a little different: they were showing off their kids' shoes.

According to the Smithsonian, excavations of Roman military bases have uncovered women's and children's shoes — proof that the outposts weren't all-male sort of places. Further research revealed a bit more, and found those shoes were more than just foot-coverings. University of Western Ontario archaeologist Elizabeth Greene says that it's the children's shoes that were the most interesting, as it seems they were designed to reflect the social standing of their parents.

The shoes, she explained, were decorated to correspond with the places they were found, including a baby's shoe found in the quarters of the post's commander. That particular shoe was a miniature version of a boot typically worn by a man of high standing, right down to the expensive leather and iron studs on the sole. And there's more to it, says Greene: the leather was "cut into an elaborate fishnet pattern," which was commonly done for those to show off the color of their socks, which was also an important indicator of social status. The moral? Romans wore socks with sandals. You're welcome.

When the beauty of a court lady meant constant pain

Foot binding started in China in the 10th century and was only outlawed in the early 1900s, although the BBC says that it continued beyond that. The process is painful, and starts when a girl is just 5- or 6-years-old. That, says the Smithsonian, is when the girl's feet were first soaked in hot water and her nails were clipped. Then, after a massage with oil, her toes — except for the big one — were broken and bound against the sole of her foot. Then, the arches were broken: the foot was bent double and bound, and the girls were forced to walk in order to speed up the process. Bandages were changed every few days, infection was cleaned, extra flesh was removed, and rot was encouraged.

The perfect foot was just three inches, and it was called the golden lotus. Four-inch feet were respectable silver lotuses, and five-inches or more were iron lotuses (i.e., completely undesirable).

The entire practice was said to have been inspired by Yao Niang, a 10th century dancer who broke and bound her feet, then gained the attention and favor of the emperor with her dance. Eventually, other court ladies started to do the same and it became a status symbol: these were women who didn't need to work... or walk. Gradually, the procedure became more widespread, and became less about status and was seen more as an indication that a woman would be a good wife.

When obesity was a sign that life was good

Beauty standards are always changing, and if you look back to the Renaissance, you'll find that obesity was prized — and according to Sermo, it wasn't just because people could look at you and know that you had plenty to eat.

There was more they could tell about a plump person, too: sure, the wealthy were able to eat their fill, but a voluptuous form also suggested they could afford a decent place to live, had access to things like clean water and sanitation facilities, and weren't susceptible to the sort of diseases that were ravaging the poor and lower classes. A heavy figure also indicated that you weren't the type of person that needed to be laboring in the fields all day, you could hire someone else to do that sort of thing.

In some areas, obesity remains a status symbol. In 2007, the BBC reported on Nigeria's fattening rooms, places where women could go to pack on the pounds. They spoke with Happiness Edem, who went to a fattening center before her marriage to Morris Eyo Edem. As a prince, Edem felt as though he required a fat wife. A thin one? "People will think I am not rich... If a woman is not fat and has not gone through that process, she does not qualify for marriage."