Leopold And Loeb: The Truth About America's Original Evil Geniuses

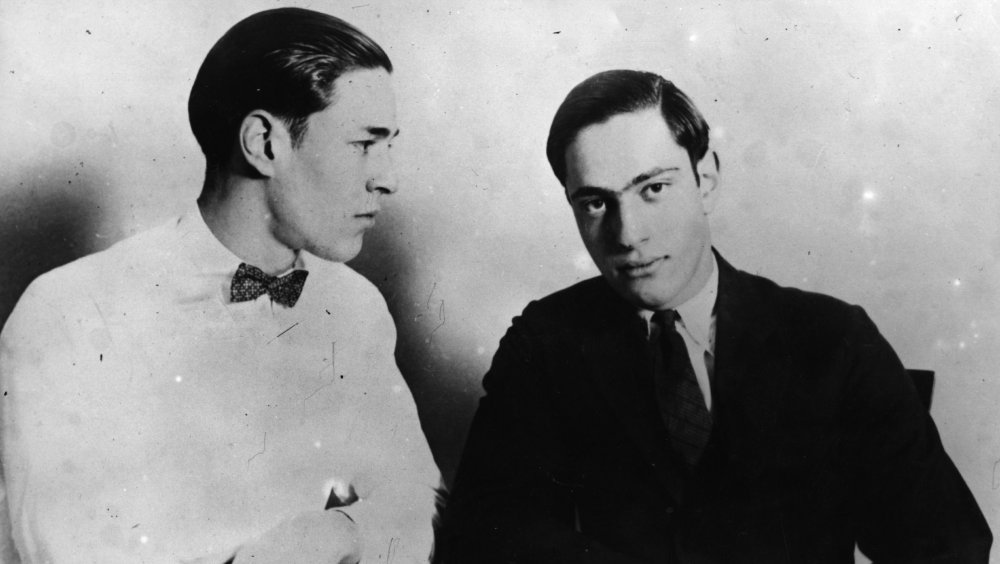

Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb met when they were children, growing up in the well-to-do Jewish neighborhood of Kenwood, on Chicago's South Side. Both were privileged, intelligent, and their futures seemed to be full of potential.

Leopold was the son of an affluent businessman and heir to his shipping and manufacturing fortune. He was a quiet and studious child, with a great interest in birds. By the time he enrolled at the University of Chicago at the young age of 15, he had already been published twice in the prestigious ornithological magazine The Auk.

Loeb, whose father was the vice president of Sears, Roebuck & Company, also came from substantial wealth. He was attractive, charming, and extremely smart. He graduated from high school at just 14 years old, but did not adjust to university life well. He attended the University of Chicago for two lackluster years before transferring to the University of Michigan, but he was miserable there, too, and eventually turned to alcohol to cope, according to Smithsonian Magazine.

The criminal and the 'Übermensch'

The two young men reunited in Chicago in the fall of 1923, and their friendship grew more intimate, especially on Leopold's part. Leopold became infatuated with his handsome, charismatic friend, so much so that he would agree to go along with almost anything Loeb planned, including crime. By the spring of 1924, the pair had racked up a history of vandalism, theft, burglary, and even arson.

But these crimes weren't enough to satisfy Loeb's desire for fame and recognition. Loeb wanted to make the newspapers with a crime so sensational that the press couldn't help but take notice. Although Leopold would later claim that he only went along with the plan "to please Dick" (via PBS), he had his own interest in committing the perfect crime. Leopold was studying Nietzsche, and had become particularly fascinated with his concept of the Übermensch, or superman. He believed Übermenschen did not have to abide by the same rules as average men, because of their superb intellect and abilities. Even murder was permissible, because the Übermensch stood outside of the regular moral code.

They ultimately decided the only crime that was worthy of their grand ambitions would be the kidnapping and murder of a child. If they included a ransom, they reasoned, they could also use this as an opportunity to make some money. They also didn't think they would get caught.

The 'perfect crime'

On May 21, 1924, the two young men forced a 14-year-old boy named Bobby Frank into the back of their rental car, where they murdered him with a chisel, according to PBS. They then disposed of his body in a culvert south of the city. By the time they sent the ransom note to Frank's family demanding $10,000, the young boy was already dead.

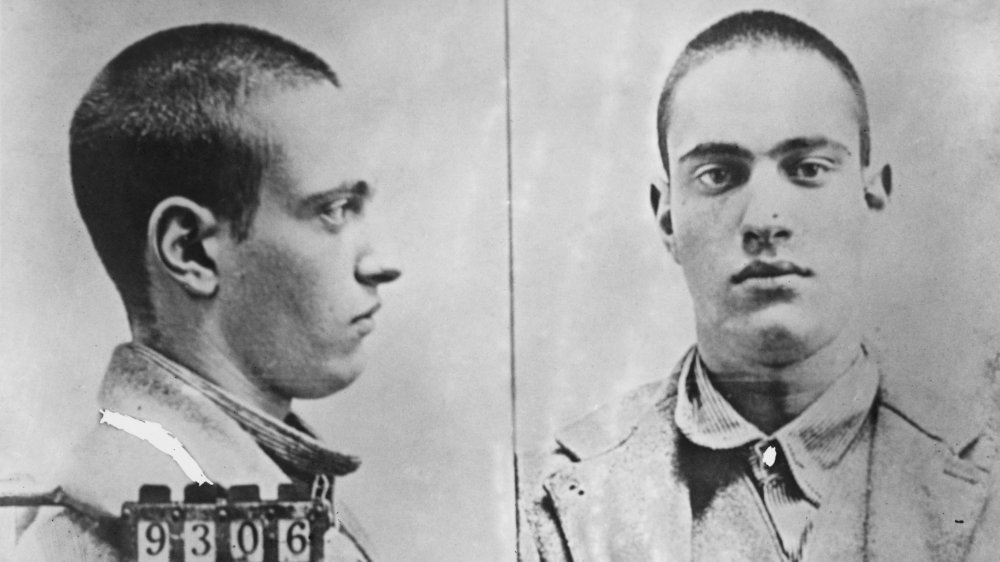

But it wasn't the perfect crime after all. Frank's body was discovered just one day later, leaving no chance they would be able to collect the ransom money. Furthermore, Leopold had lost his glasses at the scene, and Chicago police were easily able to trace them back to him. Within a week, Leopold and Loeb were the case's prime suspects. Only 10 days after committing their so-called "perfect crime," they confessed to the murder.

There was no question that they would be found guilty. Their parents' only hope was to save them from receiving the death penalty. To do this, they hired the country's best lawyer: Clarence Darrow. The famous attorney put in a guilty plea, and Darrow, a staunch opponent of the death penalty, made a compelling case that their lives should be spared.

'Nature made them do it'

Darrow argued that the young men were not entirely to blame for their crime. Instead, he claimed their youth, their traumatic upbringings, and their psychiatric state all contributed to their decision to murder Bobby Frank, and these circumstances should exempt them from receiving capital punishment. In Darrow's closing arguments, he stated: "Nature made them do it, evolution made them do it, Nietzsche made them do it. So they should not be sentenced to death for it," via PBS.

After a 32-day trial, both men received the sentence of life in prison. They were both transferred to Stateville Penitentiary in Illinois, where they maintained a friendship behind bars until Loeb was murdered by a fellow inmate in 1936. Leopold was a model prisoner, attempting to improve conditions at the penitentiary, teaching in the prison school, and working in the prison hospital, according to the UMKC School of Law. He was paroled in 1958, and lived in Puerto Rico until his death in 1971.