What It Was Really Like To Attend A Play At Shakespeare's Globe Theater

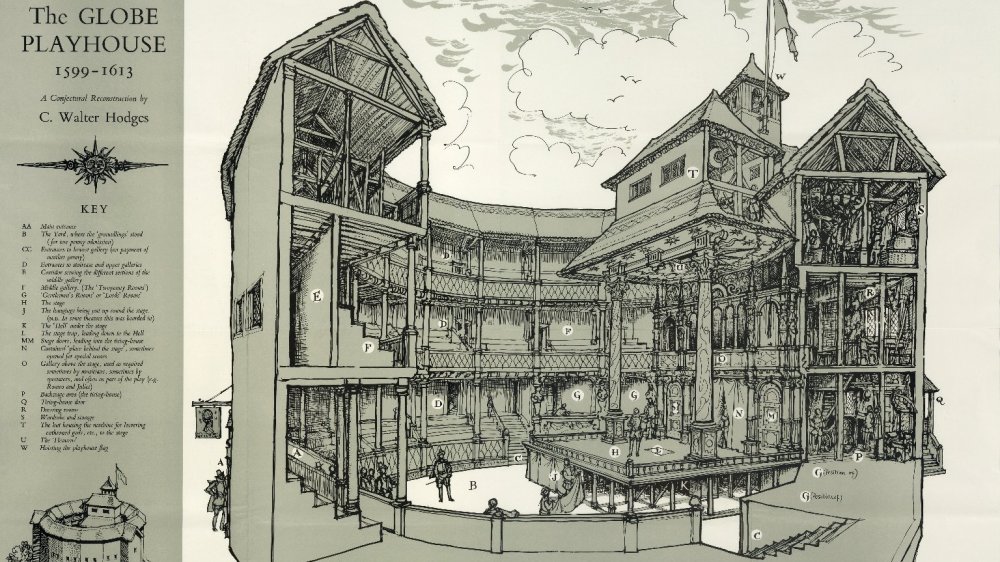

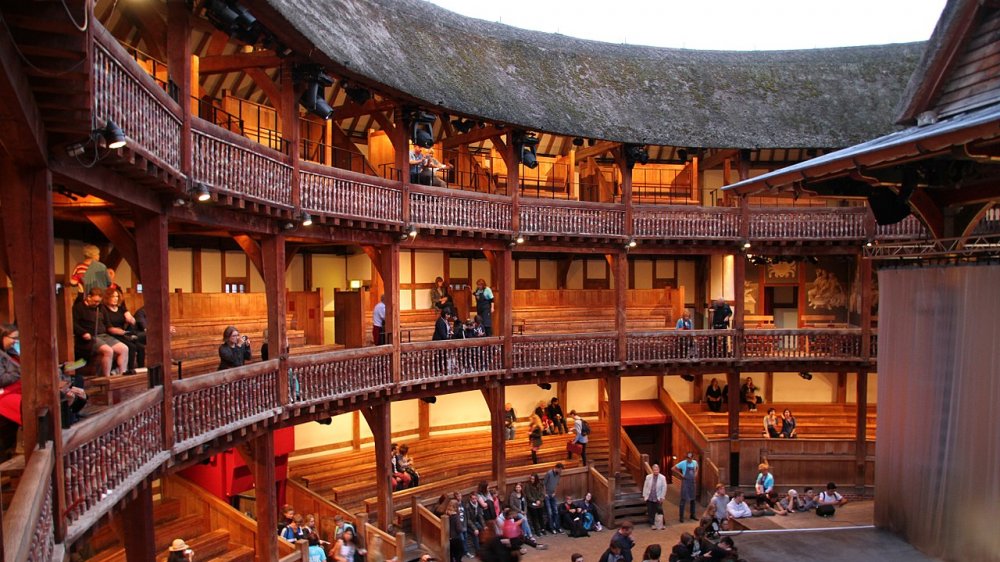

For modern people, the Globe Theater is now legendary. During the time when Shakespeare was acting and writing there, things were much different. The original Globe, built in 1599 and standing until 1613, according to the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, certainly garnered a lot of acclaim and respect for the playwright and actors. Rebuilt and reopened in 1997, the new Globe Theater is now in a respectable part of South London.

The original Globe, which stood only a couple of blocks away from its modern successor, was in a very different time and place. The neighborhood, Southwark, was then just outside the bounds of the city. Taking advantage of its somewhat extralegal situation, Southwark was packed full of less than refined entertainment and, sometimes, dubious characters.

Attending a play at the Globe Theater during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I or her successor, King James VI and I, would have been a boisterous, sometimes stinky affair. Audience members were known to talk back to actors and even throw food onto the stage when they didn't think the play was going well. On at least one occasion, they also had to flee a burning theater after a special effect had gone wrong. So, if you're planning to attend a theater performance in the manner of the Tudor and Stuart audiences that flocked to the Globe, be prepared to get loud, get smelly, and probably get kicked out of the building.

Everybody came to see plays at the Globe Theater

All sorts of Londoners, from servants to nobles, visited the Globe. To stand in the area just before the stage with the other "groundlings" would only cost you a penny, says the Folger Shakespeare Library. That meant you would be without seats, instead standing beneath an open sky in a dirt yard. To actually sit down in the balcony would have cost you twopence, or about half the average cost of food and drink for a man in one day.

For comparison, seats in indoor theaters, which would operate regardless of weather but could only accommodate a limited number of audience members, typically cost a minimum of sixpence. Theatergoers in either place could also spend their money on food and drink, as evidenced by the bottles and oyster shells excavated at historic playhouses.

Upper-class people could also be seen at the plays, says Shakespeare's Globe. A high-rolling Venetian ambassador bought out the priciest seats there in 1607 so that he and his entourage could enjoy Shakespeare's Pericles. They would have sat underneath the roofed area of the Globe, probably with cushions and most certainly with an excellent view of the stage. All the better to avoid the riffraff milling about in the yard just below them.

You would never see the Queen at the Globe

While even the stinky groundlings might see a lord or lady in the theater, they would never have seen a king or queen. Appearing in public was already a bit of an ordeal for a royal, much less slumming it with the hoi polloi at the Globe. Despite what movies like Shakespeare in Love would have you think, Queen Elizabeth I never, ever appeared at the Globe or any other public theater.

Instead, monarchs simply told the actors to come to the palace and do the play there. It was in the players' best interests to do so, given that a royal could bankroll their work for years. In 1603, Queen Elizabeth died and was replaced by her successor, James VI of Scotland and I of England. According to the British Library, James was such a fan of the theater that he became the patron of Shakespeare's theater company, the Lord Chamberlain's Men. The group quickly renamed themselves the King's Men.

Royals are also said to have dictated some creative decisions. Queen Elizabeth loved the character of Falstaff so much that Shakespeare brought him back for The Merry Wives of Windsor, reports Biography. Supposedly, Elizabeth was so eager for more raucous Falstaff content that she pressured Shakespeare to finish the play in two weeks. However, the busy, Catholic-leaning Shakespeare probably wasn't best buds with the equally busy, definitely Protestant queen.

Audience members were tempted away by beer and bears

Southwark, the neighborhood of the Globe Theater, was a rowdy, turbulent place to be. According to History, this thriving entertainment center had a very seedy reputation, in part because it was technically outside of the city of London. For much of the city's history, anyone traveling south out of London had to go through Southwark. That encouraged the spread of taverns, which, in turn, gave rise to a red light district. As time went on, other entertainment options became popular, including numerous playhouses. The first, The Theatre, was built by James Burbage in 1576.

The Globe, which opened in 1599, reports British History Online, was, at the time, just the latest theater in a crowded market. During the late 16th century, visitors to Southwark would have had four distinct playhouses to pick from. This meant that the players at the Globe had to work hard to attract audience members.

Many distractions could have kept people from buying a ticket, from the taverns, to the brothels, to the ever-popular sport of bear baiting. The activity of tormenting a captive bear was so well-known, says History, that it was even referenced in Macbeth. Bear-baiting arenas, where bears engaged in bloody fights with dogs for the amusement of onlookers, were a prime Southwark attraction. Even Queen Elizabeth I was said to be a fan of the brutal pastime, though some critics decried it as inhumane. Bear baiting was banned by Parliament in 1835.

Shakespeare's audience loved gore

Though many modern people have the impression that Shakespeare's work was a mannered, high art sort of affair, the truth is that he needed to write plays that would sell. This meant that much of what was performed at the Globe Theater had to appeal to audience sensibilities of the time. On many occasions, that meant gore, gore, and more bloody gore.

According to the Proceedings of the Modern Language Association, the blood and guts of Shakespeare's plays were a necessary thing to underscore the high drama and tragedy of works like Titus Andronicus or Macbeth. For audiences, it could have been that they would only believe something was really serious or vengeful if they saw the gory, physical evidence of a character's wrath and pain.

The Globe's audience may have also been more used to death and violence than modern viewers, says the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust. Public executions acted as a kind of twisted entertainment of the day, with beheadings and hangings often attended by large crowds. The facts of life in an agricultural setting, or an urban setting with poor medical care, could also be fairly gruesome. Other bloody entertainments, like the highly popular bear baiting arenas, were close by the Globe in the Southwark neighborhood.

Special effects were a big deal at the Globe Theater

To enhance the experience of watching a play in the Globe, and also to attract audience members away from the temptations of bear baiting, taverns, and the red light district, playhouses had to get creative. One part of their attempts to market the experience of watching a play was to pump it up through special effects.

The players of Shakespeare's day didn't exactly have electric lights or remote-controlled blood packs, but they got pretty ingenious nonetheless. According to Shakespeare's Globe, stagehands could reproduce the sound of thunder simply through drums. If they were feeling a bit more adventurous, they could also roll a heavy cannonball across the "Heavens," the covered area just above the actors' heads.

Thunder required lightning, so people behind the scenes would occasionally play with fire. A resinous powder was used with a candle to create a bright flash, or else the company would employ a firecracker. Some ingredients used here, like sulfur and saltpeter, found in gunpowder, could make a terrible stink when lit.

On a less smelly note, the Globe was also equipped with trapdoors in the Heavens and the floor of the stage. Humans and supernatural characters like gods and demons could make surprising appearances by utilizing these semi-hidden entrances and exits.

The stage was pretty empty

Though special effects and costumes could get pretty elaborate, the actual set dressing of Shakespeare's Globe Theater was quite spare. According to the Folger Shakespeare Library, there's little evidence that the acting company at the Globe put much effort into set design. Actors would have had pieces of furniture, like chairs and tables, necessary to carry out directions in the script. They would have also been given props mentioned in the play, like swords in Macbeth or the poisonous goblet in the final scene of Hamlet.

Otherwise, they had to rely on lavish costumes and Shakespeare's language to grab audience members' attention. Also according to the Folger, the actors' clothing was the real set piece in almost every London play at the time. Acting companies, including the one occupying the Globe, would have spent a large part of their budget on costumes made out of lush materials like velvet, silk, and lace. In many cases, these could be secondhand pieces from actual nobles.

This meant that a certain suspension of disbelief was required from the audience, maybe more than modern theatergoers would be willing to grant. Actors would have made their entrances and exits in plain view, without the benefit of handy props like greenery to hide behind.

The Globe Theater probably smelled awful

Attending a play at the Globe would have required something of a strong stomach. Between the hygiene standards of the day and the smell of various stage effects, the theaters of Southwark would have smelled pretty rank to modern noses. Hopefully, people of the Tudor area would have at least been used to the odors that wafted throughout the theater.

Though people really didn't bathe very often, says Shakespeare's Globe, they might not have smelled as vile as you think they did. Tudors frequently switched out their underclothes to handle body odor, frequently washed their hands and faces, and threw on a bit of perfume if it was available. Literature at the time even gave advice on how to best clean one's teeth.

Humans still generate lots of stink, though, and the hard-working people among the groundlings might have been pretty funky. Shakespeare's Globe also notes that their snacking added to the smell. Visitors complained of the stink of garlic and beer that came from the pit in front of the stage. Some writers, says the BBC, even called the put-upon groundlings "stinkards."

The audience didn't keep quiet

Nowadays, audiences in theaters expect a pretty quiet experience. They go into a darkened, hushed playhouse and sit patiently, enjoying the efforts of the hardworking actors onstage. There will probably be polite clapping at the end. Not so for the audiences at the Globe.

Watching a play in Shakespeare's lifetime was a pretty rowdy experience, reports ThoughtCo. From the groundlings to the fancy folks sitting above them, many people snacked on food during the performance. You wouldn't have heard the quiet crinkling of a candy wrapper coming undone but the much louder noises of someone cracking open oysters, digging into a meat pie, or loudly belching after taking a swig of beer.

If the audience wasn't sufficiently entertained by the action onstage, they might simply walk around and chat with their neighbors. According to the BBC, it wasn't unheard-of for the Globe to turn into a social affair in this manner. If the actors grabbed attention by being simply bad at their jobs, the audience could get involved in a more negative fashion. Accounts say that people sometimes threw food at the actors and spoke back to them when the mood struck them.

The Globe's actors sometimes spaced out

It wasn't easy to be an actor at the Globe Theater. Though some of best known actors could garner some small measure of fame and fortune, that wasn't the case for most players of the time. Instead, they faced hours of hard work, indifferent or even hostile audiences, and little preparation time. According to ThoughtCo, company members were expected to do a bit of everything. Newbie actors especially had to rise up through the ranks, meaning that the young man playing Ophelia one day would also be required to act as a stagehand or dresser for the next production.

Even the higher-ranking actors still had plenty of work on their plates. On average, theater companies produced a staggering six different plays a week. This tight turnaround sometimes meant that actors had only a single morning to memorize their lines. By the time the afternoon light filled the Globe and made it just right to perform, says Shakespeare's Globe, they were expected to have their parts down. Never mind the fact that they also had to juggle multiple parts and plays the entire time. No wonder that some company members lost track on occasion, spacing out right in front of a waiting audience.

No one expected to see women onstage

Women were allowed to watch plays alongside male audience members at the Globe, but they had better not dare to get up onstage and pretend to be a respectable actor. Officially, women couldn't perform onstage in England until 1660, says the Folger Shakespeare Library. Shakespeare, who died in 1616, would have never worked with a female actor at his theater. Instead, girls and women were played by boys and men.

Outside of England, women did join theater companies, though they sometimes had to deal with a bad reputation for sexual licentiousness. When those troupes did visit England, actresses and all, they faced tense opposition. The earliest recorded instance of women acting in England happened in 1629, says Early Modern Low Countries, when a French company performed at Blackfriars Theater in London and at the court of Henrietta Maria, the queen consort and a fellow Frenchwoman.

While Henrietta seems to have behaved herself, the audience at Blackfriars booed the women offstage. One contemporary viewer wrote, "Glad I am to saye theye were hissed, hooted, and pippin-pelted from the stage." Women wouldn't be welcome on British stages for another 30 years.

The Globe Theater burned to the ground

By 1613, things were going pretty well for the Globe and its actors. Shakespeare was one of the most famous playwrights of his day. The theater company enjoyed the patronage of King James himself. Finances were great, the acting was good, and audiences flocked to the Globe. Then, the theater burned down.

The fire began on June 29, 1613, says BBC's History Extra. Audiences were watching an afternoon performance of All is True, now known as the history play Henry VIII by modern audiences. During a scene where King Henry makes a big appearance, stage direction called for cannon fire. No one would have dared to fire an actual cannonball near the crowded theater, but the company did use real cannons with real gunpowder and cloth wadding in the barrel.

When the effect went off, a cannon fired a piece of flaming wadding into the thatched roof of the theater. At first, no one seemed to notice the smoke curling up from the dry vegetation that made up the thatching, but the fire quickly drew attention. As it grew and took over the roof, the audience flooded out of the theater. After only an hour, the Globe was little more than a smoking pile of timbers.

Though the Globe was rebuilt in 1997, players were reluctant to stage Henry VIII, reports Reuters. It was restaged there in 2010, where, thanks to a modern fire alarm system and better special effects, everything was fine.

You may have seen Shakespeare himself onstage

In a busy theater company, everyone had to do their part. In smaller groups, actors would be called upon to work as stagehands, costume dressers, carpenters, and more. Even Shakespeare, at least in his early days with the Globe Theater, would step out onto the stage and play a role now and then.

Many sources seem to forget that Shakespeare was an actor as well as a playwright, says The Atlantic. That might be simply because actors were rarely high up in the hierarchies of Tudor and Stuart society. But Shakespeare was an actor for many years, apparently doing just fine in a world where the bad players got oranges and apples lobbed at them from the audience. He may not have drawn crowds like the comedic Will Kemp or leading man Richard Burbage, but Shakespeare the actor seems to have been respectable.

Maybe Shakespeare himself was a little reluctant to proclaim his past work as an actor after the critics got to him. Writer Robert Greene, a snobby Cambridge-educated man, played into the stereotype of a shady and unlearned actor in his pamphlet, Green's Groats-Worth of Wit. There, he called Shakespeare an "upstart crow" who "supposes he is as well able to bombast out blank verse as the best of you." Anyway, said Greene, he's not as good as the real artists who went to university. Ouch.