The Crazy History Of Necromancy Explained

Necromancers have a bit of a bad reputation. Say that you play one in D&D, or any of the scores of online games that have them as an option, and you're bound to get a bit of a funny look before people start backing away. The mere mention of them conjures up images of raising the dead, of leading scores of skeletons and rotting corpses into battle, of sending the dead and diseased into a city to swarm the streets.

The necromancers of our favorite fantasy games and stories were based on a very real practice that tried to cross the boundaries between the living and the dead. For as long as mankind has lived, loved, and lost, we've wanted to know what comes after. We've wanted to reach out to people just one last time, to say the things that went unsaid, to see them one final time. It's a powerful thing, and here's where necromancy comes in.

The history of necromancy goes back thousands of years, and it hasn't always been about creating undead hordes. In fact, it's really never been about that. Let's talk to — and about — the dead.

Necromancy isn't what you think it is

Necromancy, it turns out, wasn't originally about raising the dead at all. According to Andrej Kapcar of Masaryk University's Department of Archaeology and Museology (via ResearchGate), the general term "necromancy" refers to any and all divination practices that involve the spirits of people who have passed on. The precise details of just what that includes has changed a lot over the course of centuries, but necromancy got its start when we started forming complex ideas about the afterlife. Once we believed spirits went somewhere, it wasn't that far-fetched to believe that if we just knew how to dial the celestial telephone, we could reach them.

The idea goes back a long way. Shamanism — which predates Greek antiquity — involved practices where a shaman would enter a trance and then guide souls to the underworld, try to rescue the soul of someone who was sick, deliver messages to the dead, and ask them questions. It has long been believed that spirits have access to knowledge that the living don't, and ancient shamans could tap into that knowledge.

It's also argued that necromancy's origins go back further still, to the Stone Age practice of ancestor worship. Religious beliefs that venerate the dead are among the oldest in the world, with rituals involving the remains of those who have passed on going back to the Neanderthals and to Jericho, with ritual sites dated to between 7220 and 5850 BC.

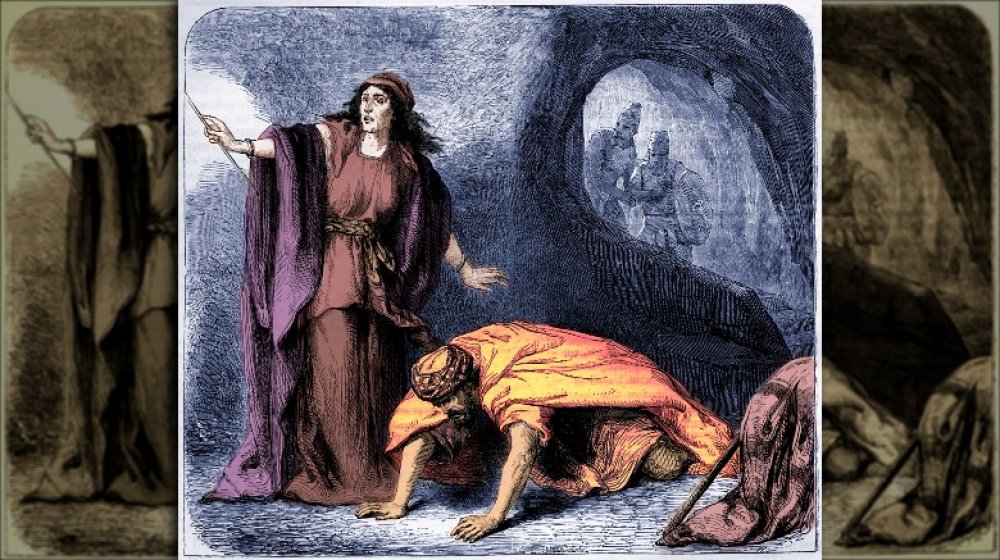

Early necromancers: the Witch of Endor

Necromancers even get a mention in the Old Testament — specifically, 1 Samuel 28:3-25 (via Britannica).

She's called the Witch of Endor, and she's consulted by Saul, the first king of Israel. Even though the Brooklyn Museum notes that Saul himself outlawed necromancy and communication with the dead, he asked her to use her talisman to summon the spirit of the prophet Samuel. He wanted to know the outcome of an upcoming battle against the Philistines, and it wasn't good news for Saul: The spirit told him that he and his sons would all die in battle, and Israel would fall.

Feminae says there are a few interesting things going on here with the evolution of the story and the imagery that has been used to tell the tale over the centuries. Originally, it was usually Saul at the center of the images, and the woman was referred to as either a necromancer, a sorceress, a phitonissa, a diviner, or a medium. It wasn't until the 15th century that images started to show her front and center, summoning the spirit of Samuel, and it was only in the 16th century that she was given the title "witch." The narrative had shifted, from being about a king who wanted to know the future to the woman who could summon the dead to tell it to him.

The Greek obsession with speaking to the dead

Necromancy was common throughout Greek myth, and it was dark stuff.

Take the tale of Orpheus. Not only did he head into the underworld to rescue his beloved Eurydice (who disappeared the moment he looked back, the one thing that Hades had told him not to do), but his decapitated head did some serious prophesying (via Britannica). His ultimate fate wasn't pleasant: He was decapitated by the women of Thrace, but his head continued to sing and speak. Biblical Archaeology says that it ended up on the island of Lesbos, where it was discovered by the Muses and put into a cave, where so many people came to consult him that Apollo got jealous and demanded that he stop.

That's skull necromancy, the practice of consulting the decapitated head of a person for some inside knowledge. Orpheus wasn't the only head that spent part of his afterlife giving prophecies: Stockholm University says that Sparta's king Cleomenes was said to have kept the head of his friend Archonides in a jar, preserved in honey, brought out to be consulted on important matters. Magical texts from ancient Greece specify some of the ways the skulls were to be prepared in order to open up communication between the living and the dead.

It doesn't always work out for the necromancer

Necromancy in ancient Greece could definitely end poorly, as it did for Periander, the tyrant of Corinth. He summoned his dead wife to find out where she'd buried some money, and while she told him, she also reminded him that he'd gotten too frisky and violated her corpse. She demanded a sacrifice of clothing, which resulted in his orders that the women of the city publicly strip and hand over their clothes.

Biblical Archaeology says that Periander wasn't the only one to find out that dabbling in necromancy could backfire in a terrible way. Pausanias of Sparta was credited with leading Greece to victory over Persia, but after the battle that kicked off the Classical Age of Greece, he descended into tyrannical madness and a bit of treason. He headed to Byzantium, where he fell in love with a girl named Cleonice and had her brought to his chambers one night. The lights were off to protect the modesty he was about to take, and when she arrived, knocked over a lamp, and woke him from a tormented sleep, he leaped up and killed her.

Now harassed by her ghost, Pausanias consulted with an oracle, who revealed that her spirit said all he needed to do to be at peace was to return home to Sparta. Easy! So, he went back. Unfortunately for him, Sparta was waiting to bring him up on treason charges, which they did ... then, they bricked him up inside the wall of a temple.

The Necromanteion of Ephyra

Greek oracles were consulted on matters of extreme importance, and one of the most famous was Apollo's Oracle at Delphi. National Geographic says it was at Delphi where priestesses called the Pythis gained access to Apollo's prophecies, but they weren't the only oracles doing business.

There was another at the top of a hill where three of the five rivers of Hades met. It was the junction of Cocytus, the river of wailing, Acheron, the river of woe, and Pyriphlegethon, the river of fire, and the site includes subterranean rooms and ruins with walls that are 11 feet thick. This was the home of the Oracle of the Dead, a place spoken about in Herodotus's Histories (via Atlas Obscura).

Greek High Definition says the Necromanteion of Ephyra was active around the fourth century BC, and visitors who wanted to consult with the dead would descend into the chambers and perform rituals in order to open lines of communication. Just how legit the oracle was is up for debate, as they also note that archaeologists have uncovered certain mechanical devices believed to have been used to create the illusion that those rituals were working. Still, ancient texts suggest the oracle was incredibly popular: It was even the place where Odysseus was said to have summoned Teiresias to learn what the future had in store for him.

Necromancers of the Middle and Far East

Some ancient Greek sources say their necromantic knowledge came from the Middle East, and here's where things get extra surprising. Andrej Kapcar of Masaryk University's Department of Archaeology and Museology says (via ResearchGate) that while some — like Moses — warned against communing with the dead, those who were actually doing it really didn't see anything weird, creepy, or evil about it.

The magi — sometimes called Sha'etemmu, or the Chaldeans, or the Manzuzuu, depending on the area — held some major sway in Egypt, throughout the Middle East, and into India. They were widely respected and often consulted by rulers who wanted to know what the future held. And it makes sense: The souls of the dead were said to be closer to god and to have access to a wealth of information about the past, present, and future. The idea that the living could ask them about things was perfectly normal.

In Egypt, necromancers were associated with the cult of Osiris, and here's the weird thing: Today, we might think of necromancers as raising the dead, but in ancient Egypt, they were behind the rituals and incantations that prevented malevolent spirits from possessing a body and reanimating it. Meanwhile, the magicians of the Sabians were said to get their powers from their influence over the stars and turned that power into prophecy, conjuration, and necromancy.

When necromancy became about something more

Necromancy underwent a major change in the Middle Ages, and starting in around the 13th century, it became much darker. A practice that had largely been written off as superstition started getting the attention of scholars across Western Europe, who began to categorize magic. First, there was "natural magic," which the Encyclopedia of Renaissance Philosophy describes as "active endeavors" where power was drawn from the world around the magician. Think of it as things like chemistry.

While natural magic could coexist quite happily with Christianity, the other kind of magic couldn't. That was necromancy, which had grown from its original meaning to include black magic and anything that tried to control a realm that good, living Christian folk just weren't meant to know about. According to Sciencia, it came down to natural vs. supernatural, and dabbling in the supernatural was something that the Church was vocally opposed to.

The more Christian writers wrote on the subject of necromancy and other types of sorcery, the further from its original definition it got. It became a "fusion of practices of different origins," including things like animal sacrifice, spells, exorcism, and astral magic, and along the way, the spirits that necromancers had been conjuring for generations took on a whole new aspect: They were confused and merged with demons, and suddenly, necromancy was the darkest of dark arts.

The surprising role of religion in necromancy

While Christian writers like Isidore and Thomas Aquinas were talking about how necromancers were busy summoning demons, actual necromantic texts were telling a completely different story. Sciencia says that there's not a single surviving necromantic text that says anything about making a pact with Satan, mocking God, or ridiculing Christianity. In fact, the opposite is true.

At the core of a necromancer's power was the ability to command spirits to obey and answer them, and that power, it was believed, came directly from God. The 14th-century Catalan magician Berenguer Ganell wrote, "Magic is the art that teaches one to exercise coercive control over good and evil spirits through the name of God [...]"

Necromancers, it followed, tended to hold a deeply profound belief in God and prepared for their rituals with fasting, prayer, and washing with holy water. Texts suggest that the general thought among necromancers was that they were something outside of good and evil, capable of achieving a "holy state" that spirits of all kinds had no choice but to obey. So, it shouldn't be entirely surprising that monks and clerics were among the foremost practitioners of necromancy, with alchemists, astrologers, and medical professionals close behind.

The reasons for necromancy

Necromancers summon and speak to the spirits of the dead, but here's a question: Why? Richard Kieckhefer, a professor of Religion Studies and History at Northwestern University, says (via Sciencia) that there are three main reasons for a necromancer to reach out to the great unknown:

First, it could be to gain forbidden knowledge. Spirits, it was believed, could tell a summoner things about the past, present, or future that they would otherwise never know, and that covers a wide range of things, from the outcome of a battle to uncovering the identity of a murderer.

Second, there was a belief that spirits could aid in the manipulation of others. For example, in the Cantigas de Santa Maria, there's a song that tells the story of a priest who dabbled in necromancy in order to compel demons to force a young girl to fall in love with him. They did — and she did — but the Virgin Mary stepped in to save her and condemned the priest to hell.

And third, there are the illusions. Necromancers were believed to have the ability to compel spirits to create illusions on a grand scale, from grand banquets to hordes of troops sweeping across the battlefield to terrify an enemy into retreat. Some of the illusions were a bit more than just images, as there are more than a few stories of necromancers summoning mysterious black horses that could take them anywhere in the world (via "Medieval Magic").

It wouldn't be necromancy without the rituals

According to "Medieval Magic," the necromantic rituals that are preserved in historical texts suggest there were actually two parts to the act. Not only were rituals designed to summon the spirits of the dead or demons, but there were parts — like the drawing of circles — that were solely to protect the necromancer from whatever he might end up summoning.

Sometimes, specifics got pretty dark. It wasn't unheard-of to have a component of an animal sacrifice, but sometimes, Sciencia says, "sacrifices" were more along the lines of offerings like honey, milk, salt, or ash. Circles — which have long been believed to have protective powers — were common, along with the inscription of astrological characters and the use of magic items like candles and swords. Spells were often recited, and, strangely, these often called out the names of Christian figures like Christ or involved reciting prayers or psalms.

At least one form of ritual required an assistant, and that was prediction. Prediction was usually done with mirrors, glass, or liquids in a receptacle that formed a reflective surface, and the images that would form on the surface could only be seen by a young virgin boy.

Even necromancy goes out of style

According to Folklore Thursday, necromancy sort of faded from history post-Renaissance, but it didn't so much disappear as it just sort of ... got rebranded.

As history moved on from the Enlightenment to the Victorian era, people started to think differently about what happened to the dead and how they should be honored. That's also about the time the Fox sisters were capitalizing on a rumor they'd heard around town. Their house was haunted, it was said, and when mysterious noises started happening, that's when Headstuff says Kate and Maggie started claiming they'd been in contact with the spirit making the sounds. They called him "Mr Splitfoot," and it wasn't long before neighbors started asking them what was going on. The first time they demonstrated their "abilities" in public was on November 14, 1849, and that soon escalated into national tours and the development of spiritualism, which essentially involved holding séances to summon spirits.

Even though the whole thing was repeatedly debunked, the movement continued on well past what the Fox sisters had started. It's understandable, after all: The desire to speak to a loved one just one last time is a powerful thing.

Modern necromancy

Folklore Thursday says that while things like the Ouija board and spiritualism have their roots in necromancy, there's one religion that is still based around the entire idea. That's Quimbanda.

According to Learn Religions, Quimbanda is practiced mostly in Brazil, and it's described as one of the "African diasporic religious belief systems." At the center of the religion are spirits called Exus, Pomba Giras, and Ogum, which practitioners call upon during rituals called trabalhos.

The Exus are a group of male spirits, and they're typically consulted by practitioners hoping to get otherworldly intervention in material matters, like bringing someone to justice or signing business contracts. The female spirits are the collective called the Pomba Giras, and they're typically called on to settle relationship issues, or they're often asked to bring some good, old-fashioned bad luck on a rival. The final spirit, the Ogum, is associated with mediation and crossroads.

Rituals have similarities with medieval necromancy in that they typically involve an offering — particularly rum for the Exus and beer for Ogum — along with food, flowers, and candles. The spirits are then asked for help according to specific rituals, which only the initiated are allowed to conduct.