Things The Indiana Jones Movies Get Right About History

Everybody loves Indiana Jones. He's an iconic American character, combining a two-fisted sense of adventure with a sincere love of knowledge (with a spice of imperialist privilege). He respects other cultures while being perfectly willing to steal their precious artifacts, and he does stuff like ride a submarine and casually threaten people with a bazooka. What's not to love?

Of course, these are classic adventure films and not documentaries. You're not wrong to suspect that the Indiana Jones films take a lot of liberties when it comes to the existence and function of ancient artifacts — not to mention the existence and function of actual civilizations. While the Bible makes the existence of the Ark of the Covenant clear, for example, there's no evidence it has ever been found, or that it could be used as a superweapon carried by fascist armies.

On the other hand, you might be surprised at the things the Indiana Jones movies get right about history. Steven Spielberg and George Lucas were willing to sacrifice historical accuracy in exchange for a better story, but they made efforts to ground all of Indy's adventures (yes, even The Crystal Skull) in something approaching historical reality. Doubt us? Read on and find out all the stuff that's actually mostly correct in these classic movies.

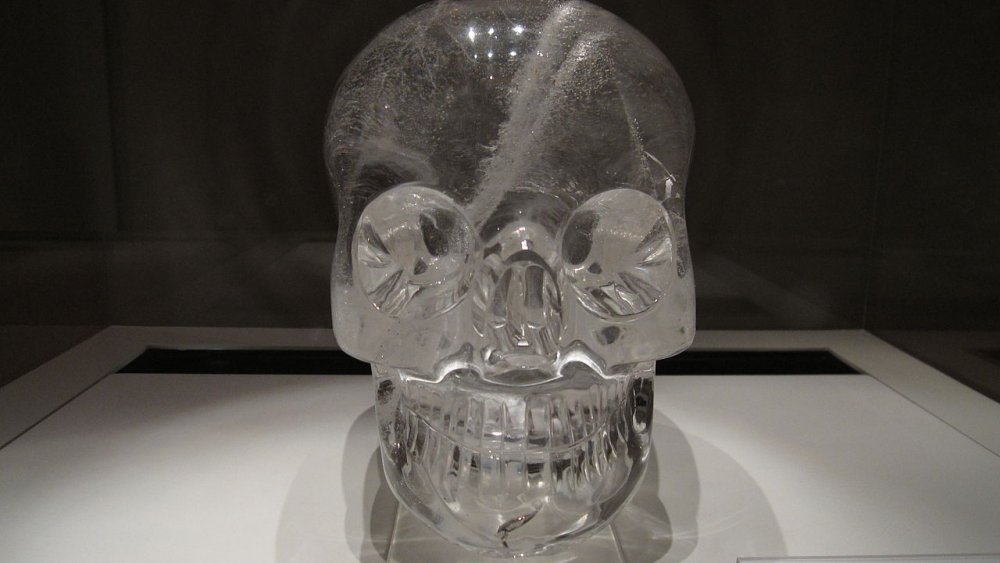

There really are Crystal Skulls

Even fans of the Indiana Jones films complain about the fourth (and so far, final) film, Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull. Set in the 1950s, the film followed an aging Indiana Jones as he battles Soviet agents to claim an ancient crystal skull, and the story gets a little ... weird. After chasing down historically and spiritually meaningful objects like the Ark of the Covenant or the Holy Grail in previous films, a crystal skull seemed a bit hokey.

Crystal skulls are a real historical phenomenon, though scientists and historians are dubious about their provenance. As National Geographic notes, some examples of crystal skulls are believed to be thousands of years old. Some historians believe that some of the crystal skulls in museums around the world date back to the Aztec Empire — or an even older civilization. Some think they might even go back to the lost continent of Atlantis.

Others, however, think most of the skulls were made in the 19th century and sold to gullible tourists. Something else the film got right? According to Gizmodo, the prop crystal skull used in the film is so accurate, the producers were sued by the director of the Institute of Archaeology of Belize because it is an exact copy of a skull stolen from Belize years ago.

The Nazis loved their archaeology

Watching the Indiana Jones films, you might wonder if the Nazi Party in Germany was really that excited about archaeology. Sure, it makes for a great story, but would the Third Reich really have poured so much money and manpower into huge archaeological digs?

Turns out, yes they did. As noted by historian Bettina Arnold, the Nazis were big on the idea that geographical locations were linked to ethnic groups and the culture those groups developed. They saw archaeology as a way to buttress their argument that the German race was descended from a pure "Nordic" race that had historically occupied a vast area of Europe. They based their claim on the land Hitler eventually invaded on these theories.

Arnold notes that many of these efforts were led by Nazi bigwig Heinrich Himmler, who had no scientific training and believed strongly in the occult. He used archaeology as a way to prove that a "German" civilization had existed long before other cultures, thus proving its superiority. As How Stuff Works points out, Hitler also sent teams of archaeologists into the countries he conquered to prove that Germans had lived there long ago, and thus he was just reclaiming Germany's ancient lands.

So yes, the Nazis were big on archaeology and did in fact work up huge digs around the world for nefarious purposes, just as the Indiana Jones films show.

Like in Raiders of the Lost Ark, the Nazis were believers in the occult

If you're thinking that the Nazis and Adolf Hitler were probably too concerned over conquering Europe and committing genocide to get involved in kooky quests for the Holy Grail, you would be ... dead wrong. The Nazis were totally into kooky quests for various occult items they absolutely believed would grant them superpowers.

As reported by The Washington Post, the Nazis as a group of people were absolutely ready to believe in all kinds of crazy stuff. The beliefs that some Nazis actually held included that Germans were descended from the people of Atlantis, that werewolves protected good Germans from Slavic vampires (yes, not just any vampire, but specifically Slavic ones), and that Satan is the actual hero of the Bible.

The Nazis, under Hitler's leadership, were equal-opportunity believers and were actually very focused on acquiring legendary artifacts like the Holy Grail and the Ark of the Covenant. As The Daily Beast reports, Hitler was always obsessed with acquiring these artifacts. As the war began to turn against the Nazi regime and things got kind of grim back in Berlin, Hitler became increasingly convinced that ultimate victory lay in acquiring some nuclear-level holy stuff, like the Grail or the Spear of Destiny. So it's actually not too crazy that Indiana Jones would stumble on a whole lot of Nazis racing to steal various religious icons.

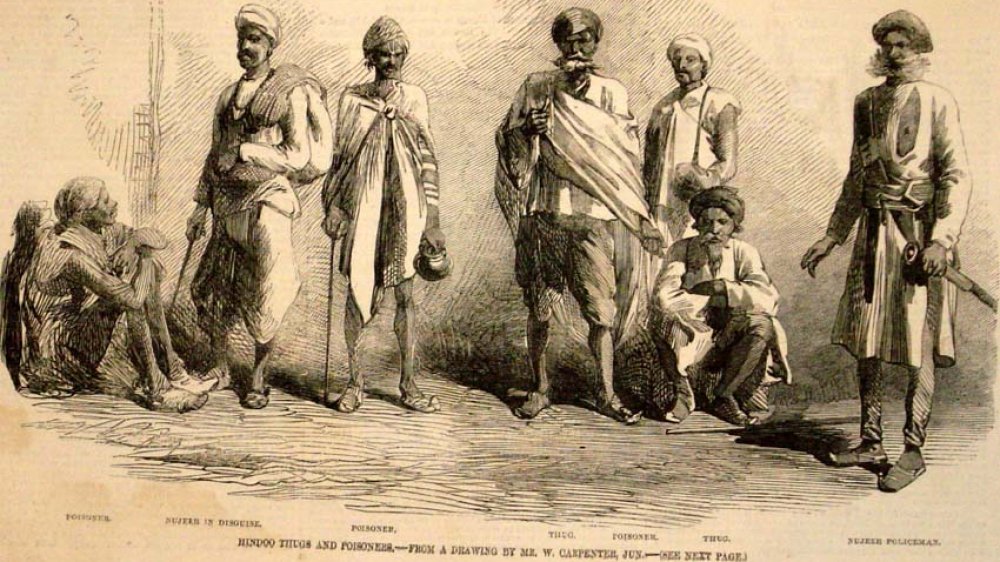

The Thuggees in Indiana Jones were real

In Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, our favorite two-fisted archaeologist stumbles onto a Thuggee cult that is kidnapping children. The leader of the cult rips beating hearts from people's chests and sports supernatural powers. That's some crazy movie plotting, right there.

Except, it's not totally far-fetched. As made clear by author Mike Dash, The Thuggees were a real group that existed in 19th century India — in fact, we get the word "thug" from them. As reported by NPR, the actual Thuggees were more of an organized group of thieves and murderers than a religious cult. They purportedly used deceit and charm to fall in with travelers at a time when the British ruled India, then waited until night and strangled everyone before robbing them.

As The Guardian notes, the Thuggee threat inspired a lot of crazy stories, and this is where the whole Kali Cult stuff came into play. Stories grew in the telling, and soon the Thuggees were super-powered cultists protected by local rajahs. When the British brought in a guy named William Sleeman to wipe out the Thuggees, however, he did so using techniques that would form the basis of modern police work, not magic or occult forces. By the time Indiana Jones arrived in India, the Thuggees were long stamped out after Sleeman's eradication. As NPR notes, many scholars now believe "the Thuggee Cult was in many ways an invention of the British colonizers as a way to better control India."

The Tanis Excavation was essentially accurate

In Raiders of the Lost Ark, Indiana Jones follows clues to a massive archaeological excavation in the ancient Egyptian city of Tanis. The Nazis have been there for months, searching for the location of the Ark of the Covenant, but only Indy has the crucial clue to its hiding spot. The excavation is immense, employing hundreds of local laborers and tons of Nazi equipment.

It's all very plausible. First of all, Tanis is a real place. In the film, it vanished after a cataclysmic, biblical-level sandstorm. According to National Geographic, the reality is a little different. Tanis was located on a tributary of the Nile River that offered tremendous natural resources and geographical advantages — but the course of the river shifted, the area silted up and became a desert, and slowly Tanis declined and was abandoned. For centuries it was forgotten, making it seem like a "vanished" city.

So the filmmakers obviously drew inspiration from Tanis and took some storytelling liberties with it. But when it came to the excavation they portray, they got it absolutely correct. According to the Chicago Tribune, the massive excavation work depicted in the film is more or less exactly how those kinds of big digs would be run at the time. As archaeologist William Parkinson notes, the scenes of Tanis in the film look remarkably like actually excavations done by a guy named Henry Field in Iraq at the time.

There was a real Indiana Jones

Indiana Jones is a fantastic character. He's everything you want in an action hero, but with a respect for history and knowledge. Harrison Ford looks so good in his fedora and leather jacket, in fact, National Geographic reports a spike in interest in archaeology as a career due to the films.

Of course, the real work of an archaeologist isn't nearly as adventurous. Ancient tombs are never actually booby-trapped, after all, and there aren't entire armies that need to be hoodwinked. Most archaeological work is done away from the field, cataloging and processing bits and pieces of the past. That doesn't mean Indiana Jones is totally fake. In fact, he closely resembles a real-life legend in the field of archaeology: Roy Chapman Andrews.

Born in 1884, according to Adventure Journal, Chapman moved to New York immediately after high school and took a job at the American Museum of Natural History. It wasn't long before he was in the field. He himself counted 10 times that he almost died in the course of his work, including drowning during typhoons, being charged by a dying whale, being attacked by wild dogs, by fanatical priests, falling over cliffs, several venomous snakes (and one python), and the relatively prosaic danger of mere bandits. While Andrews never squared off against Nazis over the Ark of the Covenant (that we know of), he's proof that the character of Indiana Jones isn't implausible.

The Red Scare was pretty scary

All four of the Indiana Jones films stretch history when it suits them. But the fourth film, Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, is usually seen as the worst example when it comes to its history. While the first three films dealt with religious artifacts that have deep cultural and historical significance, Crystal Skull dealt with, well, aliens. Combined with crystal skulls, a Soviet agent played by Cate Blanchett, and a motorcycle-riding "greaser" played by Shia LaBeouf, it's all very silly.

One thing that the film got right, however, was how easily someone's career could be destroyed with even a hint of communist sympathy. The most accurate moment in the movie, as film critic Alex Flood notes, is when Professor Jones loses his job when he's suspected of associating with communist agents — despite the fact that those agents kidnapped him and tried to kill him.

As Flood points out, the film is set in 1957. While the baleful influence of Senator Joseph McCarthy and his House Un-American Activities Committee was on the decline, it was still a very dangerous time to be suspected of communist sympathies, and many people were fired from their jobs simply for attending a meeting or unknowingly associating with someone who was considered insufficiently patriotic.

Western archaeologists really did steal artifacts like Indy

Most of us remember the Indiana Jones films as fun adventure stories. But a lot has changed since Raiders of the Lost Ark was released in 1981. Ironically, one of the aspects of archaeology that the film portrayed pretty accurately has become its most controversial aspect.

As The Washington Post makes clear, Indiana Jones' line, "That belongs in a museum!" sums up the franchise's attitude towards the fact that Jones is 100 percent stealing priceless treasures from poor, undeveloped countries. The idea that these cultural treasures belong in a museum thousands of miles away from their home is offered as an obvious, generally accepted truth.

As Vice reports, it is definitely a fact that Western archaeologists routinely stole precious treasures from less-powerful areas. That's why museums in London and New York are stuffed with treasure from Egypt, Greece, and South America among other places. There were hundreds of Indys throughout history, and if they didn't use a bullwhip and a revolver, they certainly stole plenty of monkey idols along the way.

Times have changed, and this aspect of the films has become increasingly controversial. Indiana Jones would not be considered a dashing hero of archaeology today — he would be considered a looter. As countries like Greece increasingly demand the return of their historical artifacts, the most accurate aspect of Indiana Jones may have to become a bit less accurate in future films.

The Brotherhood of the Cruciform sword existed ... sort of

If Steven Spielberg and George Lucas have ended their run with Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, they'd be remembered for having created a near-perfect trilogy of action-packed adventure films. The third film memorably followed Indy as he raced to locate the Holy Grail. As he does so, he encounters members of the Brotherhood of the Cruciform Sword, an ancient group of knights dedicated to protecting and keeping secret the location of the grail.

Great stuff for a story. The Brotherhood didn't actually exist — but they were certainly based on an ancient order of knights that were very real: The Knights Templar. According to History.com, the Knights were founded in the early 12th century. The Knights Templar originally existed to protect Christian pilgrims traveling to the Holy Land. They were famous for their poverty and lived on donations. As their fame grew, the Pope conferred on them many privileges, including a blanket exemption from taxes. As CNN notes, they were also rumored to be the guardians of the Holy Grail.

The Knights lost influence when Christian forces lost the Holy Land. Their exemption from taxes made them targets, and in the early 14th century, they were brutally suppressed by the King of France after they refused to make loans to him. Rumors persist that they still exist, however, and that they still guard the Grail.

The Raiders Flying Wing was based on real planes

One of the most famous scenes in the Indiana Jones film series involves Indy duking it out with an absolute unit of a German soldier while a BV-38 "flying wing" fighter plane slowly spins, its deadly propellers coming closer and closer (and eventually ending the fight in a definitive and gory fashion).

It's a fantastic scene, but even casual students of history probably realize that no such plane ever actually existed. The BV-38 was created for the film — but as Air & Space Magazine reports, the design of the BV-38 was actually taken from real-life experimental planes that the German Luftwaffe was actively working on during World War II.

The most obvious source of inspiration for the "flying wing" is the Horten Ho 229. Designed in 1943, its compact design promised incredible speed and maneuverability, and the Third Reich committed a half of a million Reich Marks to the project. It was plagued by problems, however, and never went into production. The general idea behind these planes was also being pursued by the Allies — the United States even had the Vought V-173, affectionately known as the Flying Pancake. It was a relatively short leap of logic to imagine that the Nazis had actually gotten a variant on the idea into production.

The Chachapoyans (once) existed

One of the most iconic moments in all four Indiana Jones films is the opening sequence to Raiders of The Lost Ark. Indiana Jones steals a fertility idol from an ancient tomb and is chased through the jungle by Chachapoya warriors. Most people assume both the Chachapoya tribe depicted in the film and the famous golden idol were invented for the movie. They're half right. The golden idol was created for the film — though The Washington Post notes it was based on a real Aztec idol depicting the goddess Tlazolteotl, patron of midwives and adulterers.

The tribe chasing Indy actually existed, albeit a long time ago. As noted by Archaeology Magazine, the Chachapoyas lived in an area of modern-day Peru from the early 9th century until they were destroyed by the Incas in the late 15th century. As Indy in the Classroom notes, the script explicitly imagines a tribe known as the Hovitos to be direct descendants of the Chachapoya tribe.

Of course, the Hovitos never actually existed, as the Chachapoya were wiped out, and there was no hidden tomb with an array of surprisingly sophisticated traps, including a huge boulder poised to crush looters. But credit the filmmakers with basing their fakery on real history.

Indiana Jones' black market for antiquities is real

The scene where Indiana Jones meets up with gangster Lao Che to sell him a priceless artifact in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom might seem unlikely. How many archaeologists were selling historical pieces of art and chunks of history to sketchy dudes on the black market in 1935, after all?

As it turns out, plenty. According to archaeologist William Parkinson, this wasn't uncommon in the 1930s. And as The Conversation makes clear, the practice has been very common for a very long time — and continues today. In fact, the illegal trade of antiquities is so common almost every major law enforcement entity in the world, including the FBI and the UK's Metropolitan Police, has a division dedicated to busting up these black market sales. According to CNN, the Cultural Property, Art, and Antiquities unit of the Department of Homeland Security has recovered artifacts valued at $250 million.

Maybe in 1935 elegant gangsters were running the antiquities business. Today, it's terrorist organizations like ISIS. As Vice notes, the terrorist group was making millions of dollars selling off the antiquities they looted. The worst part is, many of those stolen items will remain hidden for years to come as dealers wait until the heat dies down — or simply keep the pieces for their own private collections.