The Messed Up History Of Yellow Fever

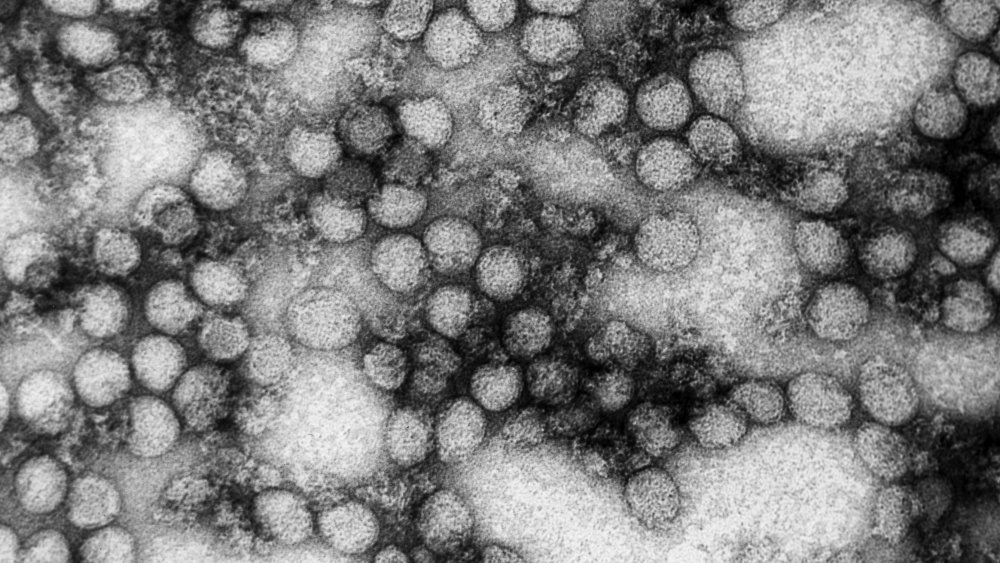

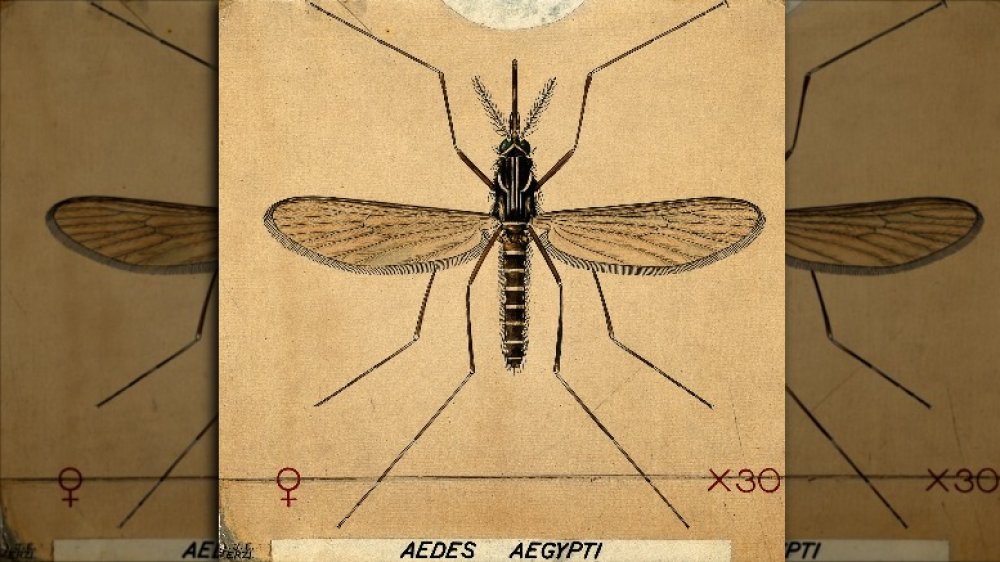

Yellow fever has been literally plaguing humanity for centuries. This viral disease, spread by a subspecies of mosquito known as Aedes aegypti, has sickened many thousands of people and struck fear into the hearts of even the mightiest generals and rulers. It's cut down the populations of whole cities. It's inspired wild theories about its origins, from miasmas to ill-fortuned planetary alignments. Intrepid doctors and scientists have built or broken their reputations on fighting yellow fever and defending others from its ravages.

In its worst form, says the Mayo Clinic, the illness can cause terrible nausea, uncontrollable bleeding, and the yellow-tinged jaundice that gives the disease its name. Even people who are struck with a mild case can be incapacitated for days or weeks at a time.

While today we have the benefit of pest control measures and vaccines to help protect us from yellow fever, we can't ignore its impact on history. Yellow fever may have helped Haiti win its freedom. It doomed the French attempt to construct their own Panama Canal. It upended the social structure of cities like New Orleans. It has changed the course of human history more than once and may continue to do so for a long time to come.

Yellow fever originated in Africa

The origins of yellow fever are difficult to tease out. Humans have only understood how it's transmitted since 1900, says the Journal of the American Medical Association, a mere blip in the long history of the disease.

We can be fairly certain that yellow fever originated somewhere in Africa, as it appears to have a long history on the continent. According to The American Plague, it's likely that yellow fever was transmitted to the Americas via the transatlantic slave trade. This theory has been around since at least the mid-nineteenth century when abolitionists sometimes painted the disease as a divine punishment for those who engaged in the deplorable practice of human slavery.

The first presumed record of yellow fever in the Americas is a 1648 case in the Yucatan, in what's now Mexico, says PBS. The details of this illness line up neatly with the observed effects of confirmed yellow fever. Other accounts hint at an earlier debut for the disease as it crossed the Atlantic. In 1643, the Caribbean island of Guadeloupe was hit by a mysterious illness inhabitants called coup de barre, which caused intense but ultimately temporary fatigue. Another illness struck Barbados in 1647, affecting and killing many people with symptoms that are reminiscent of a viral hemorrhagic disease like yellow fever.

A horrifying outbreak hit Philadelphia in 1793

While yellow fever thrives in the tropics, other places along the coasts of North and South America can be affected. In 1793, the city of Philadelphia, the largest city in the budding United States of America, would learn just how tragic this disease could get.

Yellow fever was no stranger to the British colonies or the newly independent republic, History says, with the first known outbreaks taking place there in the late 1690s. The 1793 epidemic was touched off by people fleeing an already ongoing spread of yellow fever in the Caribbean. In the summer of that year, many colonists left their island homes in an attempt to flee the sickness, not knowing that they were bringing it with them.

Soon after the travelers landed, per the Philadelphia Center for the Book, yellow fever began to spread. The situation quickly grew dire. By October, an estimated 100 people were dying of the fever daily. People saw friends and family grow ill and die in short order, growing frantic once it became obvious that they couldn't contain the spread. What they didn't know was that yellow fever was passed on through mosquitoes, which thrived due to Philadelphia's poor public sanitation.

Doctor Benjamin Rush advocated for a massive cleanup of the city, but it was too late. By the time a cold front finally wiped out the unacknowledged mosquitoes, according to the Washington Post, 10 percent of the city's residents had died.

The disease devastated colonial troops

Soldiers dreaded tropical postings because they knew that they would be facing many deadly diseases. Their commanders knew it, too, per the American Clinical and Climatological Association. Those on both sides of the American Revolution recognized that troops stationed in South Carolina and Georgia were more likely to be struck by illnesses like yellow fever than those farther north.

Overly eager military leaders like Sir Henry Clinton made it worse. Clinton captured Charleston, South Carolina for the British in May of 1780, but his soldiers grew sick along with the rest of Charleston that summer. Patriots also suffered similar issues when they tried to take British Florida in 1776 and 1778.

In the next century, French soldiers would also suffer the scourge of yellow fever as they tried to suppress the Haitian Revolution. According to Montana State University, Toussaint L'Ouverture's 1801 rebellion was actually helped by yellow fever. Nearly a third of French forces succumbed to the virus in what proved to be an exceptionally deadly epidemic. By that summer, up to 50 men were dying each day, pushing their leader, General Victor-Emmanuel LeClerc, to desperation.

As LeClerc wrote in a letter to Napoleon Bonaparte, "My health is so wretched that I would consider myself lucky if I could last for that time! The mortality continues and makes fearful ravages." Yellow fever hit the unacclimated European soldiers harder than it did the Haitian people, helping the new nation gain its independence in 1804.

It's called yellow fever because of its gruesome symptoms

Most people who become ill with yellow fever only get a mild version of the disease. Indeed, according to the World Health Organization, many people don't experience symptoms at all. Those who do usually suffer from fever, muscle soreness, headaches, and nausea. It's certainly no fun to have even the mildest version of yellow fever, but most patients recover within a few days.

A small number of patients affected by the virus aren't so lucky. They appear to make it through the initial phase of the disease, but, within a day or so, enter into a much more dangerous second stage. The fever returns with a vengeance. Organs like the liver and kidneys begin to struggle.

As the liver fails, patients develop jaundice, or yellowing of their skin and eyes. In the worst cases, an individual can begin to bleed from their mouth, nose, and eyes. Of the unfortunate few who make it this far, about half will die within seven to 10 days.

We now understand that yellow fever is a virus spread by the bite of an infected mosquito, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports. That means modern humans can take preventative measures, like insect control and vaccinations, to reduce the effects of this terrible disease. For people living before 1900, however, yellow fever must have been devastating in part because no one knew how it worked.

An outbreak in New Orleans turned tragic

In 1853, a yellow fever outbreak in New Orleans killed 8,000 people, or a tenth of the city's population, as NPR reported. New Orleans' famous above-ground tombs were soon packed with the remains of the dead, earning the city the ghoulish nickname of "Necropolis."

Those lucky enough to survive the illness gained a kind of superpower: they were immune for life. Those who were "acclimated," or were immune to yellow fever, had a better chance of securing a job or landing a romantic partner. It upended the social fabric of the city.

The aftereffects of the 1853 outbreak also created long-lasting and harmful racial stereotypes. According to Stanford Medicine, the elite of New Orleans argued that Black people were "naturally" immune to the disease. People who had to labor out of doors were more likely to be people of color in 19th century New Orleans. They were also more likely to be exposed to yellow fever as the disease-carrying mosquitoes moved freely outside. However, there is no evidence that people of African descent are biologically less likely to catch the disease than any other racial or ethnic group.

Yet, people of the time claimed that they needed to increase the slave trade and distance supposedly less immune white people from dangerous outdoor labor. It was a convenient (and fabricated) line of reasoning for a region that had already benefited from the unpaid servitude of enslaved Africans and their descendants.

It took centuries before someone really understood yellow fever

Before pioneering research proved that yellow fever was spread by mosquitoes, people latched onto a few different explanations for how the disease spread. According to Health Sciences History, some thought it was caused by "miasmas," or bad air, that emanated from trash or stagnant water. The idea was half-right. Foul-smelling areas like swamps and docks could encourage disease-bearing mosquitoes to gather and breed. The more mosquitoes in an area, the higher the chance they could pass yellow fever on to a human.

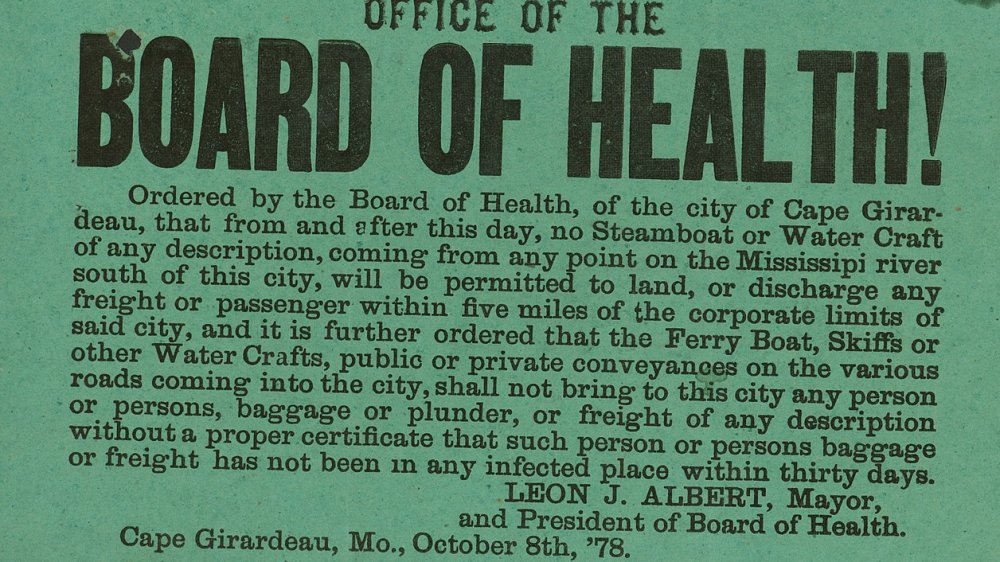

People trying to flee affected areas were met with fierce resistance, The Washington Post reports. During an 1888 outbreak in Jacksonville, Florida, residents who attempted to leave were stopped at city borders. Officials in Waycross, Georgia even threatened to tear up their own railroad tracks before they would allow a train of potentially diseased Floridians to pass through.

Other ill-informed people tried potentially harmful or unpleasant treatments. People who were already seriously ill were subjected to measures that may now seem horrifying. According to Britannica, these treatments usually focused on purging the disease out of the body, sometimes violently. That could mean doses of ipecac to induce vomiting, castor oil to encourage bowel movements, or enemas filled with cold water and turpentine.

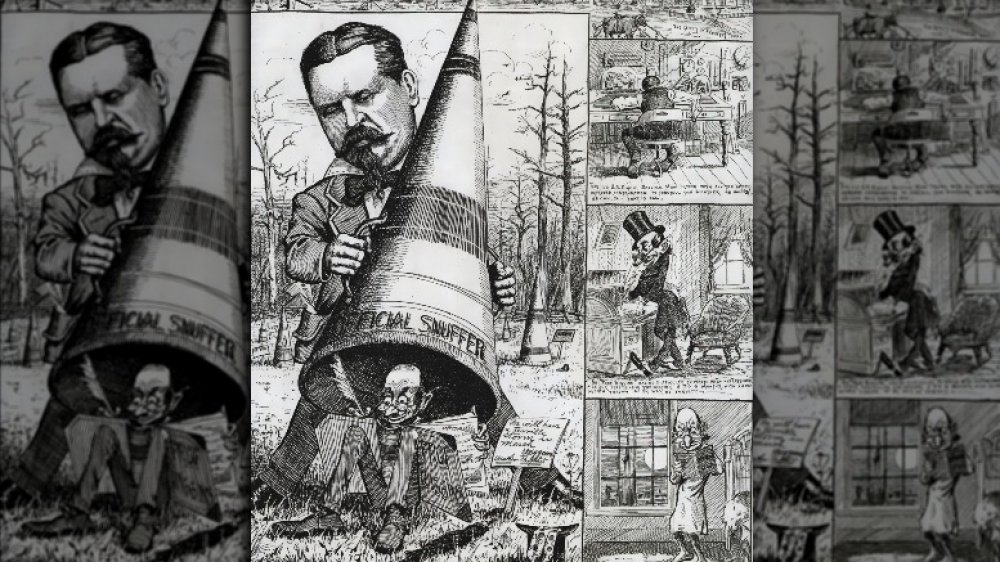

One charlatan said that yellow fever was caused by astronomical issues

Ezekiel Stone Wiggins, the "Ottawa Prophet," was an infamous conman of the late 19th century. He made his reputation as a weather and earthquake predictor, per the Ottawa Citizen, though his success rate was rather uneven.

Wiggins was spectacularly wrong on many scientific fronts, though he never admitted as much. In one of his most head-turning claims, Wiggins said that the sun was cold. More distant planets were, of course, warmer than the ones orbiting our supposedly icy star. On another occasion, he swore that a meteorite that fell near Binghamton, New York in 1897 bore a hieroglyphic message from Martians. Naturally, Wiggins assumed that Mars was already inhabited by intelligent creatures.

Though Wiggins tended to focus on meteorological matters, he wasn't above chiming in on public health issues of the day. In the case of numerous yellow fever epidemics, he was confident in the cause: planets.

Specifically, says The Martians, Wiggins blamed planetary alignment. According to his theory, if enough planets lined up, it would create on Earth "a denser atmosphere holding more carbon and creating Microbes." Wiggins at least understood that microbes could cause disease. He went on to speculate that Mars probably had a similar problem, but that their canals somehow absorbed the carbon and averted epidemics. Wiggins, it's safe to say, was disregarded by pretty much all of the scientific establishment.

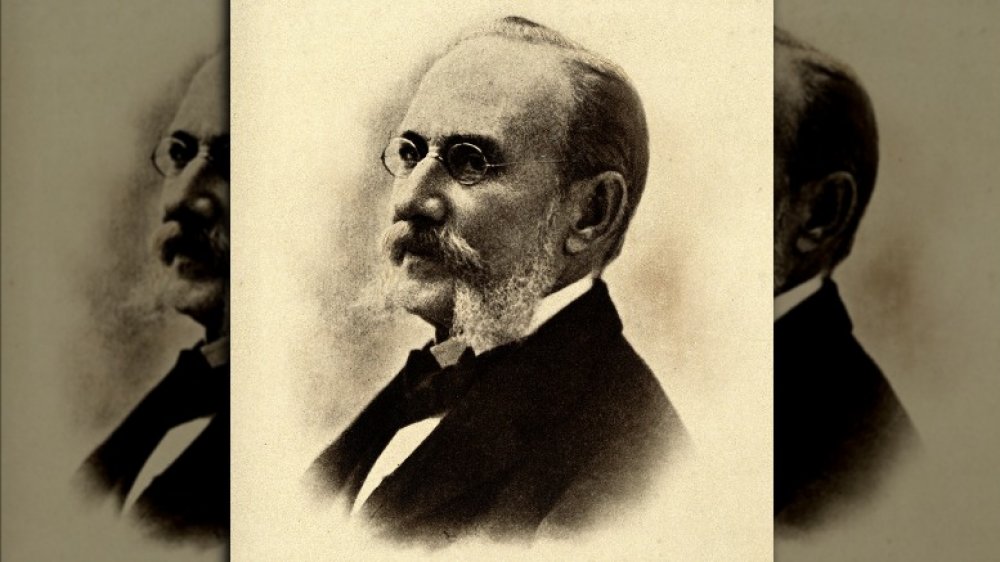

Carlos Finlay figured out the cause of yellow fever, but was ignored

In 1881, Dr. Carlos Juan Finlay, a Cuban doctor and epidemiologist, was the first to theorize that mosquitoes transmit yellow fever from affected patients to unaffected people. He also pinpointed Aedes aegypti as the specific mosquito species to blame for the spread of yellow fever. Other types of mosquitoes could not effectively host the virus, he said. As per Britannica, Finlay published concrete evidence of his findings in 1886, but his work was largely dismissed by the scientific establishment for the next 20 years.

Major Walter Reed, a well-respected U.S. Army physician, was one of the first people to take Finlay's work seriously. In 1900, according to Military Medicine, Reed traveled to Cuba as the head of the U.S. Army Yellow Fever Board, a task force assembled to discover the cause of yellow fever once and for all. The disease had hit U.S. troops hard during the Spanish-American War of 1898. Soldiers stationed in Cuba during the war suffered greatly from the virus, like many past military forces stationed throughout the Caribbean.

Reed's work, which included careful recordkeeping and some hair-raising experimental methods, finally vindicated Finlay, per Epidemiology. Finlay was eventually appointed the Chief Sanitary Officer of Cuba and later elected as the president of the American Public Health Association. He was nominated seven times for the Nobel Prize, though it was never awarded to him. Even without a Nobel medal, Finlay's legacy remains secure.

The U.S. Army conducted dangerous experiments to find the cause

Major Walter Reed, a U.S. Army physician, was part of a major effort to defeat yellow fever. Fear of the disease, the University of Virginia reports, had affected the 50,000 American troops in Cuba during the 1898 Spanish-American War. When Spain transferred control of the island to the U.S. in 1899, the problem became doubly urgent for the Americans.

When the Army appointed Reed the head of the U.S. Army Yellow Fever Board and sent him to Cuba, he was pushed to the front of the fight against the virus. As per the University of Virginia, the Board set up risky experiments to finally learn the cause of the disease. Most notably, Reed and his team created an experimental station where volunteers were exposed to yellow fever through a variety of methods.

Following a theory that it could be carried in soiled textiles, some volunteers were exposed to contaminated linens. Others were enclosed in cabins meant to seal in all manner of odors and infectious agents. Some were intentionally exposed to infected mosquitoes in a lab. The Board proved that it could only be transmitted by mosquitoes.

One researcher, Jesse Lazear, died of yellow fever he may have given himself. According to PBS, Lazear was tasked with "loading" mosquitoes with infected blood, then allowing them to feed on volunteers. He may have also intentionally exposed himself. Either way, Lazear was infected and died from yellow fever on September 25, 1900.

Yellow fever torpedoed French efforts to built a Panama Canal

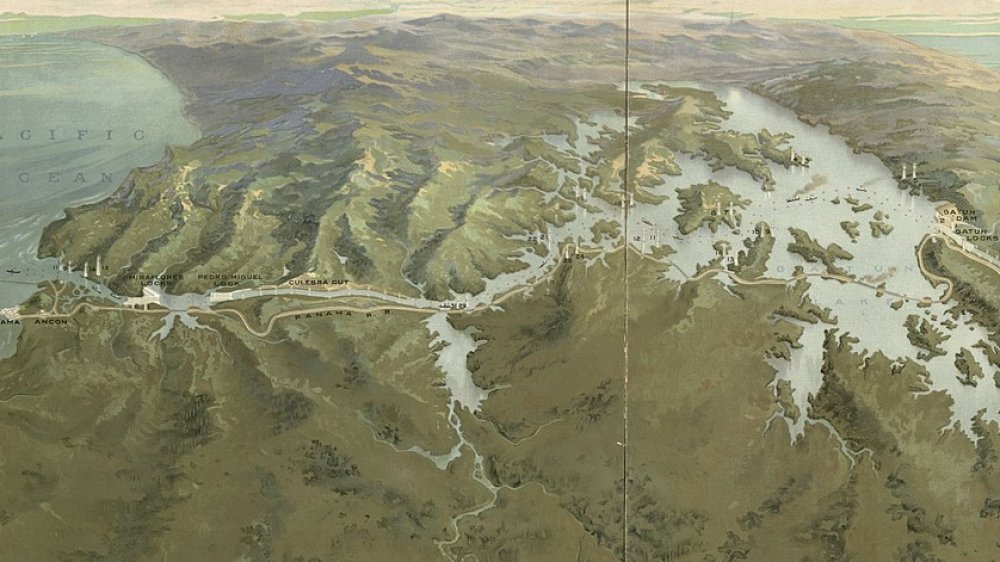

During the late 19th century, different nations were eager to build a canal across Panama. The relatively narrow strip of land in Central America was the best location for such a project, which would finally connect the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans without the need for ships to take on the long, dangerous journey around the southern tip of the continent at Cape Horn. Anyone who constructed and controlled a canal would stand to make a serious profit. The problem was, the project also stood to kill you.

The French tried their hand at the matter in 1881, according to National Insect Week. They weren't the first. Spanish settlers had failed to create a useful passage in the 16th century, while an 18th-century attempt created an economic collapse in what's now Great Britain.

Now, the French were devastated by disease. An estimated 22,000 workers on the project died of tropical illnesses, many of them afflicted by mosquito-borne yellow fever, the University of Kansas claims. All told, the failed project cost the French government $287 million by the time the efforts folded in 1889.

Developing a yellow fever vaccine was tricky

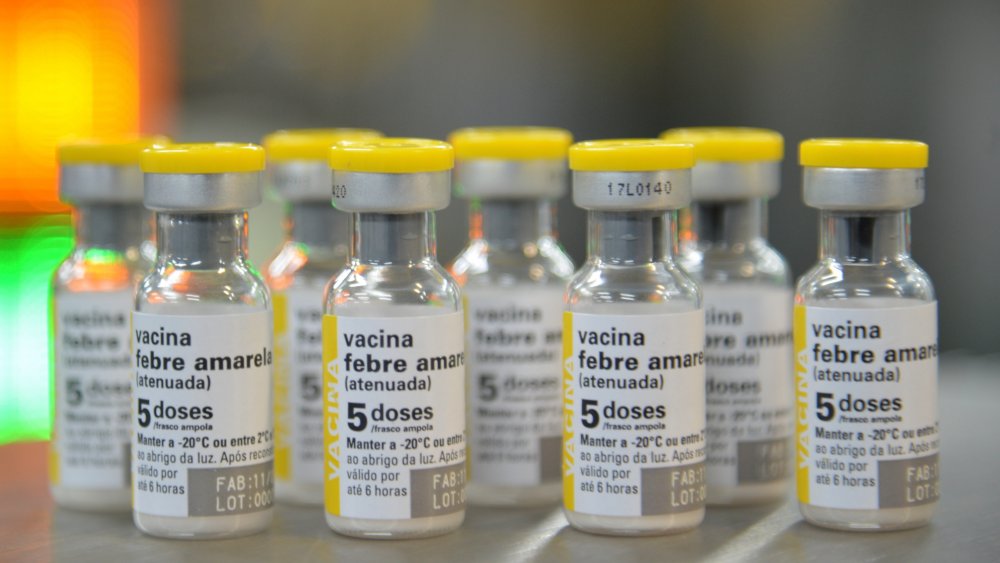

Yellow fever has proven to be a problematic disease. We know now that it's spread by infected mosquitoes and can't be exchanged directly between humans, the College of Physicians of Philadelphia reports. Once someone gets yellow fever, doctors can't do much beyond providing supportive care, like giving pain relief and attempting to lower a patient's fever. A vaccine does exist, however, giving a person an estimated 30 years of immunity, or even longer.

The path to a vaccine wasn't easy. According to the Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine, the opening of the Panama Canal in 1914 brought a large number of unexposed people to the region. People who had already survived yellow fever typically gained immunity for the rest of their life, but visitors to Panama had been given no such opportunity. Authorities generally focused on mosquito control, such as getting rid of stagnant water that attracted the insects.

The first successful vaccine against yellow fever was developed by Max Theiler, a South African virologist, per the Journal of Experimental Medicine. By 1938, Theiler had created a stable, isolated form of the virus that he turned into a highly successful vaccine. The vaccine, which has been distributed in over 400 million doses and is still in use, is now given to people living in areas where yellow fever is regularly found. For his work, Theiler was awarded a Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1951.

Yellow fever isn't done with us yet

Despite the great strides made by scientists and researchers like Max Theiler and Carlos Juan Finlay, yellow fever is still amongst us. If we're not careful, it can still infect and even kill vulnerable people.

For people living in areas where yellow fever is endemic, meaning it occurs regularly, vaccines are a smart move. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), it is a safe, cheap, and single-dose vaccine that can grant immunity for three decades, if not a person's entire life. It's also important to control the spread of the mosquitoes that can transmit yellow fever from person to person. That means measures like eliminating standing water where possible and applying pest control chemicals in other areas.

None of this means we should rest easy, however. The WHO estimates that, in 2013, up to 60,000 people in Africa died of yellow fever. In 2002, the CDC reports, a previously healthy Texas man who had recently traveled to Brazil died after contracting the same disease.

With more and more people moving to urban centers in affected areas, the risk of another devastating outbreak increases, the journal Clinics in Laboratory Medicine claims.