The Messed Up History Of The Kent State Massacre

In the 1960s and '70s, US colleges became hotspots for demonstrations as young people joined social justice campaigns like the civil rights movement, the Black Panther Party, and the movement against the Vietnam War. Many of these demonstrations were met with violence by police, National Guard, and other government actors. Some went under the radar: In 1968, highway patrolmen shot 31 South Carolina State students protesting segregation, killing three, in what became known as the Orangeburg massacre.

But what happened at Kent State on May 4, 1970, during a demonstration against the Vietnam War became the most infamous incident of government forces using fatal violence against protesters. Partly, that was because the Kent State massacre — as it became known as — was documented in footage that spread around the world: one photo won a Pulitzer Prize. And partly it was because the victims were white, which made the press and public take more notice.

The shootings ignited an already blazing anti-war protest movement and infuriated conservatives. This is the messed up history of the Kent State massacre, including the build-up, the event itself, and its legacy today.

Richard Nixon's invasion of Cambodia sparked protests nationwide

President Nixon was not known for his strong grasp on the truth (see also: the Watergate scandal.) During his 1968 campaign, he'd promised that he had a "secret plan" to end the war in Vietnam. But on April 30, 1970, Nixon outraged the public by announcing that he'd secretly authorized a US invasion of Cambodia — a neutral country — two days earlier.

Nixon had not only sidestepped Congress, Politico reported that he hadn't even told his Secretary of State and Defense Secretary. The previous year, in March 1969, Nixon had secretly ordered bombings in Cambodia, something Congress and the public didn't learn about until the New York Times published the news that May.

The invasion of Cambodia (which Nixon described as an "incursion") inflamed already strong anti-war sentiment, especially on college campuses. Students at colleges around the country went on strike and held demonstrations. Various states called on the National Guard: for example, in New Haven, the New York Times reported that 3,000 National Guardsmen were brought in over the weekend of May 1 to monitor the 15,000 Yale students and other demonstrators. Many faculty members joined protests too.

In addition to criticizing Nixon, protesters called for their colleges to openly oppose the war and to end connections to the Defense Department and Reserve Officers' Training Corps (ROTC) programs, which serve as a track into the military.

Anti-Vietnam War protests started ramping up in 1965

The wave of anti-war fervor that spread across the US in May 1970 didn't happen overnight. Initially, the movement against the war in Vietnam was run by fringe leftist groups on college campuses, especially the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS).

The US had been involved in the Vietnam conflict since the 1950s, but in 1965, President Lyndon Johnson ordered a sustained three-year bombing campaign against North Vietnam and sent in ground troops. According to the New York Times, the increased demand for manpower saw draft calls for Selective Service triple that year. The involuntary nature of the draft (which was replaced by a highly unpopular lottery system in 1969), the high casualty rate, and reports of messed up things from the Vietnam War led to increased bitterness among the public. By November 1967, 15,058 American soldiers had been killed and 109,527 wounded. The war was also costing taxpayers $25 billion a year.

More people started to join the anti-war movement. On October 21, 1967, 100,000 protesters demonstrated at the Lincoln Memorial. At the 1968 Democratic National Convention, 10,000 protesters took over Chicago's Grant Park in support of anti-war candidate Eugene McCarthy. In November 1969, 500,000 demonstrators marched on Washington to demand peace, backed up by other protests around the world.

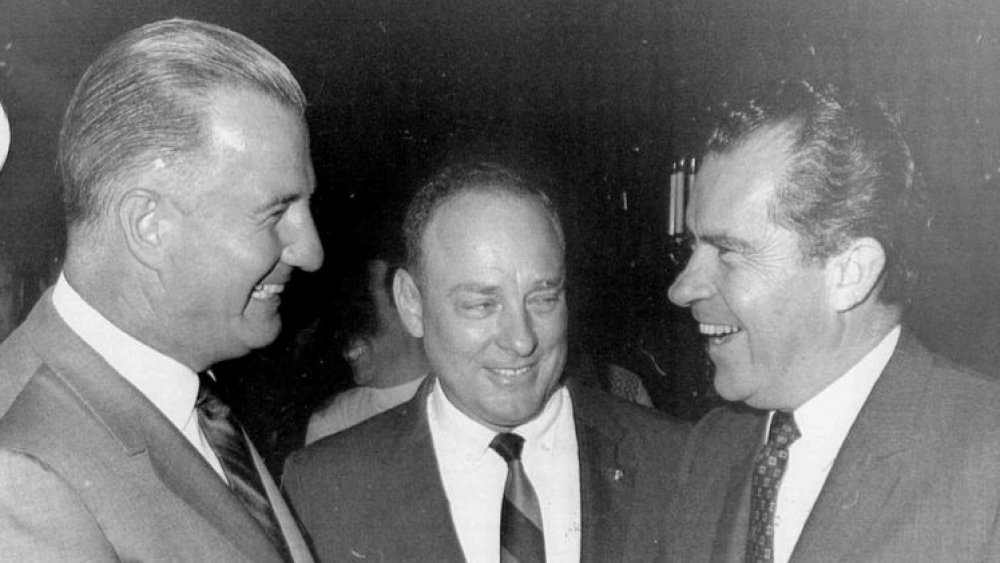

Nixon's administration painted the young protesters as lazy hippies. Vice President Spiro Agnew labeled them, "over-privileged, under-disciplined irresponsible children," while Nixon infamously called them, "Bums blowing up the college campuses."

The start of the Kent State protests

Kent State is a state-supported school that had around 20,000 students in 1970. There had been other protests on the campus. The Report of the President's Commission on Campus Unrest (published in the wake of the massacre) said that the SDS had tried to get the school's administration to ban the ROTC from campus in 1969 in a protest that led to clashes between police, demonstrators, and counterdemonstrators.

According to the report, the Kent State protests against Nixon's invasion of Cambodia started on Friday, May 1, with a peaceful rally of around 500 students. But that night, a rowdy crowd of 500 gathered in a downtown area popular with students. People started a bonfire, broke windows, and harassed bystanders and police. Mayor LeRoy Satrom closed the bars and police used teargas to dispel the crowd.

On Saturday, Satrom officially declared a state of civil emergency and requested the National Guard from Governor Jim Rhodes. That night, 1,000 people (mainly students) marched around campus to the ROTC building, which was set on fire. The National Guard arrived on campus shortly after and used teargas on the demonstrators. The next day, Rhodes visited Kent and held a press conference, where he blamed outsiders for infiltrating the campus. The New York Times reported that he described the protesters as, "worse than the Brown Shirts and the Communist element."

The National Guard had been mobilized regularly throughout the '60s

The National Guard is a volunteer militia that serves both its individual state, district, or territory and the federal government. Unlike the active-duty army, which is for federal use, the National Guard can be mobilized by the federal government or the governor to help in emergencies such as hurricanes — and, yes, pandemics — and to quell unrest.

Activating the National Guard to keep peace is supposed to be a rare event. But in the decade leading up to 1970, multiple units of National Guard had been sent to handle outbreaks of violence. Most of these were related to the racist backlash against the civil rights movement. For example, in 1962, white crowds started a violent protest when Black Air Force veteran James Meredith attempted to enroll in the University of Mississippi. President John F. Kennedy placed the Mississippi National Guard on active federal service and ordered them to restore peace. Presidents Dwight D. Eisenhower and Johnson both federalized at least one National Guard during their times in office.

The student protests that erupted in May 1970 weren't even the first time various National Guard units had been activated that year. As the Washington Post reported, in March, faced with a postal strike that was hobbling the country, Nixon had ordered the National Guard to deliver the mail. When Mayor Satrom called the Ohio National Guard to Kent, they were already deployed in truckers' strikes around the state.

How the Kent State protests escalated

By Monday, May 4, 1970, tensions had reached fever pitch at Kent State. Many students had gone away for the weekend, only to return on Sunday night to find their campus occupied by National Guard soldiers who were tear-gassing their peers. This angered even those students who hadn't been moved to protest by Nixon's invasion of Cambodia.

By this point, peaceful demonstrations had been banned by the mayor, but there was a rally planned for noon on Blanket Hill, a grassy knoll at the center of the campus. According to the Report of the President's Commission on Campus Unrest, it drew about 2,000 students, including people protesting the National Guard as well as the war, and others who were either watching or on their way somewhere else.

The students started chanting for a strike and some threw stones at the troops, who were wearing helmets and gas masks. The National Guard tear-gassed the students in an unsuccessful attempt to drive them off the hill. As the New York Times reports, the soldiers appeared to then retreat into a huddle, which some students took as a sign that they were planning to retreat. Others recall seeing them starting to walk to the top of the hill, away from the students. But instead, at the crest of the hill, the National Guard formed a line and started firing into the crowd.

Four students were killed in the Kent State shootings

According to the New York Times, the shooting lasted for 13 seconds. Many of the students didn't know that the National Guard was armed with live ammunition until they opened fire. The scene descended into chaos as people ran behind cars and dropped to the ground in an effort to escape the bullets. They watched in horror as their friends were hit.

Ellis Berns and his friend Sandra "Sandy" Scheuer had been planning to leave when the shooting started. "It just seemed to last forever. We both hit the ground. I had my arm around her," Berns told IdeaStream in 2020. When it was over, he called out to Scheuer, but she didn't reply. And then he realized she'd been shot in the carotid artery: "there was a lot of blood."

Scheuer was one of four students who died that day. The other three were William Shroeder, Allison Krause, and Jeffrey Miller. Nine others were injured, including Dean Kahler, who was paralyzed from the waist down.

After the shooting subsided, an eerie silence settled on the scene. And then students started screaming, crying, and shouting. Angrier than ever, some threatened to fight the National Guard, who apparently made no move to help the victims. Another violent outburst looked imminent — until the faculty intervened. Through a bullhorn, Professor Glenn Frank begged the students to sit down so the Guard wouldn't fire again, and then to disperse. Slowly, they did.

The photographs of Kent State shook America

The Kent State shootings weren't the first time a student protest had been violently quashed. However, student photographers made sure that this time it was thoroughly documented. Their footage was even used in the Report of the President's Commission on Campus Unrest. John Filo was a student at Kent State who took his camera to document the protest. He thought he'd missed the bulk of the action, as he'd been away at the weekend, but left his photography lab around noon to see what was happening.

When the soldiers started firing, Filo didn't realize it was live ammunition — until he saw a bullet strip the bark off of a tree. After the shooting had stopped, he saw the body of Jeffrey Miller lying face down in the parking lot with blood pouring from his head. As he raised his camera, 14-year-old Mary Ann Vecchio ran over and knelt beside Miller. Filo captured her face as she screamed in horror. The shot won him a Pulitzer Prize and became one of the most iconic photos associated with the anti-war movement and bitter protests of the '70s.

Elsewhere on campus, another Kent State student photographer captured another famous shot. According to Time, Howard Ruffner was freelancing for LIFE magazine while at college. He took a picture of John Cleary, who'd been shot in the chest, which made the cover. Cleary survived: NBC News later reunited the photographer and his subject.

We still don't know why the National Guard opened fire on Kent State

How the Kent State protests escalated from rowdy but mainly peaceful demonstration to a massacre is still a mystery. The report on campus unrest said that some students and members of the National Guard reported hearing an order to fire, and one student said that he thought he saw an officer use his pistol to give the signal to shoot.

In 2007, Kent State survivor Alan Canfora, who was shot in the wrist, released an "enhanced" version of an audio recording of the shootings, made by student Terry Strubbe. Canfora claims that in this version, you can hear someone say, "Right here! Get set! Point! Fire!" followed by gunfire. However, most people remain skeptical: covering the story, the New York Times couldn't discern these words.

It's possible that the already jumpy National Guard heard a noise that one or more mistook for a gunshot, and took that as a sign to fire. One anonymous member of the Guard — who was also a Kent State student — told IdeaStream that he didn't hear an order to shoot, "but knowing that there was firing going on, I would have more than likely emptied my weapon." According to the report, some Guardsmen also claimed that they thought there was a sniper, but no evidence for this was found later.

There was backlash from the left and right

The Kent State shootings galvanized student protesters who had already mobilized in huge numbers over the invasion of Cambodia. Demonstrations were organized at colleges that had previously been seen as apolitical. According to the New Yorker, four out of five colleges and universities saw demonstrations, while others closed in order to avoid disruption.

On May 9, striking students marched on Washington to protest against the war and the National Guard's actions at Kent State. That day, the New York Times reported that some of the protests had led to more violent clashes with police and National Guard, who used tear gas and bayonets to break up demonstrations. Some colleges were firebombed, but fortunately, no one was hurt or killed.

While many students and anti-war protesters were infuriated by the actions of the National Guard at Kent State, most people in the general public actually blamed the protesters. One student and Vietnam veteran told Ideastream, "My father's only comment was they should've shot them all ... if you were there they should've [shot you]."

Many conservatives felt that the hippy counterculture had gone too far, and blue-collar workers were enraged by students who were protesting the war when their college education was getting them a deferment from the draft. On May 8 in New York, the day after the city hosted Jeffrey Miller's funeral, construction workers attacked anti-war demonstrators in what became known as the Hard Hat Riot.

The student shooting you don't know about

Just ten days after Kent State, more students were shot by government agents. The two incidents were linked in the public mind at the time, but the second — which happened at Jackson State, Mississippi, a predominantly Black college — has largely been forgotten.

In the 1960s, tensions between the Black students and white residents of Jackson often broke out on a road that ran through the Jackson State campus. On May 13, 1970, a large crowd of students gathered on the street and the police moved to break it up. Several police vehicles were damaged. The next night, a crowd gathered again. Some people started fires and shouted at the police and highway patrolmen who had shut down the street and advanced on Alexander Hall, a women's dorm.

The report into campus unrest stated that after a couple of people threw bottles, the highway patrolmen and several police officers suddenly started firing rifles, carbines, and submachine guns into the crowd and the building. The shooting lasted 28 seconds: an FBI investigation found that Alexander Hall had been hit with 400 bullets.

High school student James Earl Green and 20-year-old recent father Phillip Gibbs were both killed, and 12 other people were injured. The report explicitly blamed police racism for the shootings, but according to a 2020 New York Times article, when victims and families sued the city and state, they lost the civil case. No one was ever charged.

None of the National Guardsmen were charged with murder for the Kent State shootings

The first legal action to come out of the Kent State massacre was not aimed at the National Guard who fired on the students, but at the students themselves. In October 1970, 24 students and one faculty member were indicted by a grand jury on various charges, most related to the burning of the ROTC building the night before the shootings. When they went to trial the following December, two pled guilty and the cases against the remaining 23 were dismissed or dropped.

It wasn't until March 1974 that eight of the National Guardsmen were indicted by a grand jury for violating the civil rights of the killed and injured students. And in November that year, the New York Times reported that Federal District Court Judge Frank J. Battisti had acquitted them all, claiming that the government had failed to prove "beyond a reasonable doubt" that the Guard had planned to undermine the students' civil rights. The families and victims turned to civil action. In 1977 and 1979, they reached a settlement of $675,000, over half of which went to paralyzed Dean Kahler.

Kent State is still seen as a turning point in US history

Many have pointed to the Kent State massacre as a pivotal moment in US history. According to the New York Times, the student protests led Nixon to call off the invasion of Cambodia on June 30, 1970. They also contributed to the ratification of the 26th Amendment in 1971, lowering the voting age from 21 to 18. This was partly because lawmakers felt that people who were old enough to be drafted should be old enough to vote, but also because they felt that young people had demonstrated political awareness.

Beyond that, the shootings were another event that symbolized the end of '60s optimism and the start of '70s disillusionment and rage. And the polarized reactions marked the early days of the intensifying political divide between America's right and left. On the one hand, violence perpetrated against the students at Kent and Jackson State and other colleges provoked many previously apolitical people to join social justice movements. But the perception of the students as violent criminals stoked conservative fears about the counterculture — and may have helped Richard Nixon, the man whose actions started it all, get reelected in 1972.