The Greatest Books Written In Prison

Prison writing has undoubtedly gone on for as long as people have imprisoned one another, but its first recorded incident was in 523 AD, when Boethius, a classical Neoplatonist philosopher, wrote The Consolation of Philosophy while imprisoned for treason. Prison writing has come to be understood as a genre of literature defined by its author's imprisonment and since Boethius's Consolation, countless others have written while imprisoned, creating works such as Martin Luther King Jr.'s "Letter from a Birmingham Jail" and Henry David Thoreau's "Civil Disobedience."

Whether creating works of poetry, fiction, or nonfiction, writing has repeatedly been used as an outlet for imprisoned people. It has also become an inlet for free people towards understanding the conditions by which society claims to rehabilitate people. While some texts have been literally written in prison using smuggled instruments, other texts reflect a person's experiences while locked up, compiled orally during their time in prison, and only given written representation after their release.

This list is by no means exhaustive and unfortunately, prison writing will continue as long as people continue to imprison one another. These are some of the greatest books written in prison.

Oscar Wilde's love letters behind bars

Oscar Wilde was widely known for his skills as a playwright by the end of 1894. But within a year, Wilde found himself notorious for his criminal conviction instead.

According to The Vintage News, Wilde had been engaged in a tumultuous relationship with a young lord named Alfred Douglas since 1891. But when Lord Alfred Douglas's father, the Marquess of Queensberry, found about their affair, he tried various means to end their relationship. Queensberry threatened to disown Douglas and even tried to interrupt the debut of Wilde's The Importance of Being Earnest.

These efforts proving to be unsuccessful, Queensberry left a note with a porter to be given to Wilde that read "For Oscar Wilde, posing Somdomite [sic]." Wilde decided to sue Queensberry for libel, but unfortunately, this brought his sexuality into the public spotlight and Wilde was soon found guilty of gross indecency and sodomy.

According to The Paris Review, although Wilde was sentenced to two years of hard labor at Pentonville, he had been deemed too weak and was instead ordered to unravel rope into strands. After he was transferred to Reading prison, he was granted the right to compose letters, provided that the pages were collected at night. During this time, Wilde composed De Profundis, a 55,000-word letter to Lord Alfred Douglas. The text is a sort of love letter, chronicling Wilde's transformation from an aesthete into a survivor. Upon his release, Wilde and Douglas reunited briefly until threats from their families finally ended their relationship.

Hans Fallada wrote in code

Hans Fallada was the pen name of Rudolf Wilhelm Friedrich Ditzen, born July 21, 1893. Throughout his life, Fallada was imprisoned frequently. In 1911, during a duel that was supposed to be a double suicide, Fallada survived and was instead sent to a mental institution. He was imprisoned again for several months in 1923 on for embezzlement, and again from 1925 to 1928.

Fallada struggled with alcoholism and drug addiction all his life and, per the Independent, was once again arrested and committed to the Neustrelitz-Strelitz psychiatric institution in 1944 for drunkenly shooting at his ex-wife, Anna Issel, with a pistol.

Fallada was known in the literary community for works such as Bauern, Bonzen, und Bomben (Farmers, Bigwigs, and Bombs) and Kleiner Mann—was nun? (Little Man, What Now?). When the Nazis came into power, Fallada sought to avoid political controversy, for example, with the "quite unpolitical" book Wer einmal aus dem Blechnapf frißt (Who Once Eats From the Tin Bowl). While the Nazis attacked his text for its humanizing depiction of convicts, many others considered him opportunistic for continuing to publish under the Nazi regime and taking notes from Joseph Goebbels himself.

During his incarceration, Fallada composed A Stranger in My Own Country: The 1944 Prison Diary and The Drinker, writing in a deliberately illegible scrawl, sometimes writing in code so he wouldn't get in trouble for his "passive resistance" against Nazism. The manuscripts wouldn't be deciphered until several years after his death.

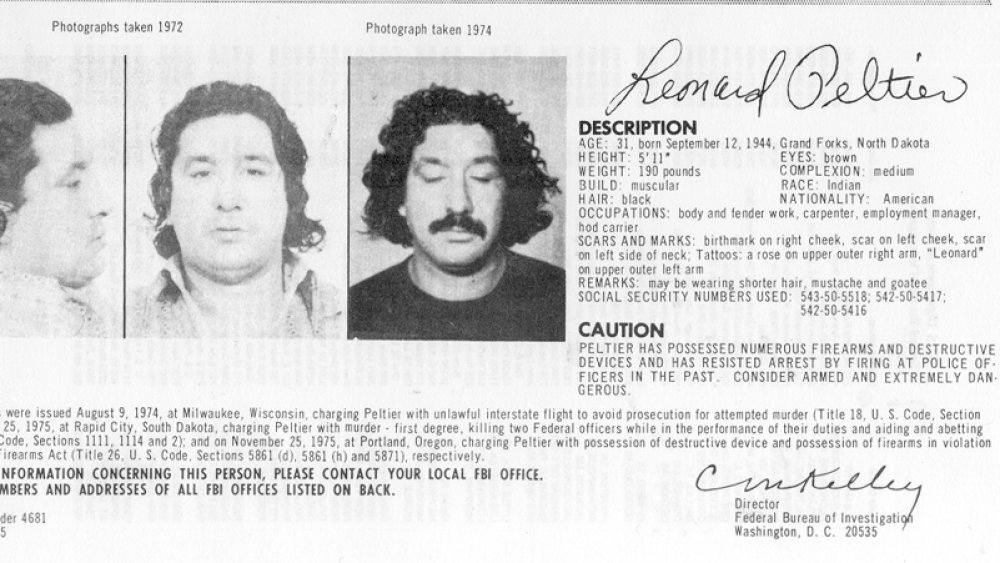

Leonard Peltier's two life sentences

Part of the American Indian Movement, Leonard Peltier, an Ojibwa-Lakota enrolled in the Turtle Mountain Chippewa tribe, was convicted in 1977 for the murder of two FBI agents. According to The New York Review of Books, Peltier, along with Bob Robideau and Dino Butler, were among the participants of the shoot-out with the FBI at the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota in June 1975. While Robideau and Butler were later acquitted based on a self-defense plea, Peltier didn't fare so easily. Having fled to Canada, he was arrested and extradited back to the United States in 1976 and because of a hostile judge, he wasn't allowed to make the same argument of self-defense.

While Peltier has consistently denied murdering the agents and the government admitted that they don't know for certain who fired the final shot that killed the agents, Peltier remains imprisoned and continues to serve his two life sentences. According to Amnesty International, his recent petition for parole was denied in 2009 and he won't be eligible again until 2024.

During his imprisonment, Peltier wrote and published Prison Writings: My Life Is My Sun Dance in 1999. The book is a memoir that passes through his childhood, recollecting the years of Eisenhower's tribal terminations, and runs through his time spent imprisoned. Connecting his own imprisonment to the condition of Indigenous people around the world, Peltier himself has become an international symbol for the continuing struggle of Indigenous people as well as political prisoners.

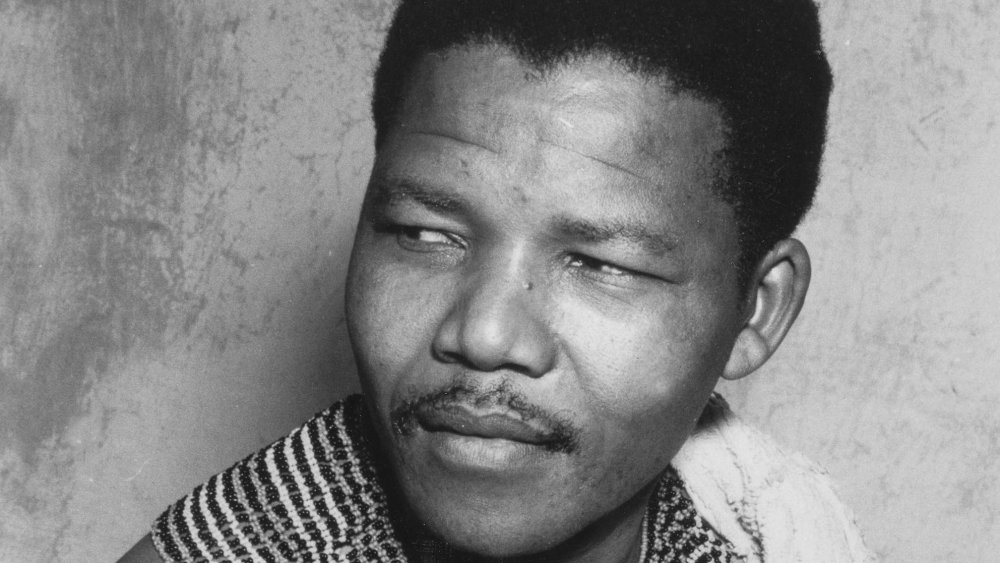

Nelson Mandela's conversations with himself

After joining the African National Congress in 1942, Nelson Mandela campaigned against the South African government and its racist system of apartheid for 20 years. Mandela was arrested in 1962 for having orchestrated a national workers' strike the previous year. He was sentenced to five years, but he was brought to trial again in 1963 for political offenses and was sentenced to life imprisonment.

Mandela was imprisoned from November 1962 to February 1990. During these 27 years, he wrote diaries and drafted letters that later came together to form the book Conversations with Myself. As noted by Booktopia, Conversations with Myself contains not only Mandela's prison writings but his journals written while on the run in the early 1960s as well as speeches written during his presidency. Through this collage-work, the text becomes a literary album, an amalgamation of the disparate moments that spanned Mandela's life.

According to the foreword to Conversations with Myself that was written by Barack Obama, this amalgamated text offers a glimpse into the transformations that a person undergoes throughout their life. And along with its behind-the-scenes look, it reminds the reader that no one is perfect, but it is the imperfections that give people their transformative qualities.

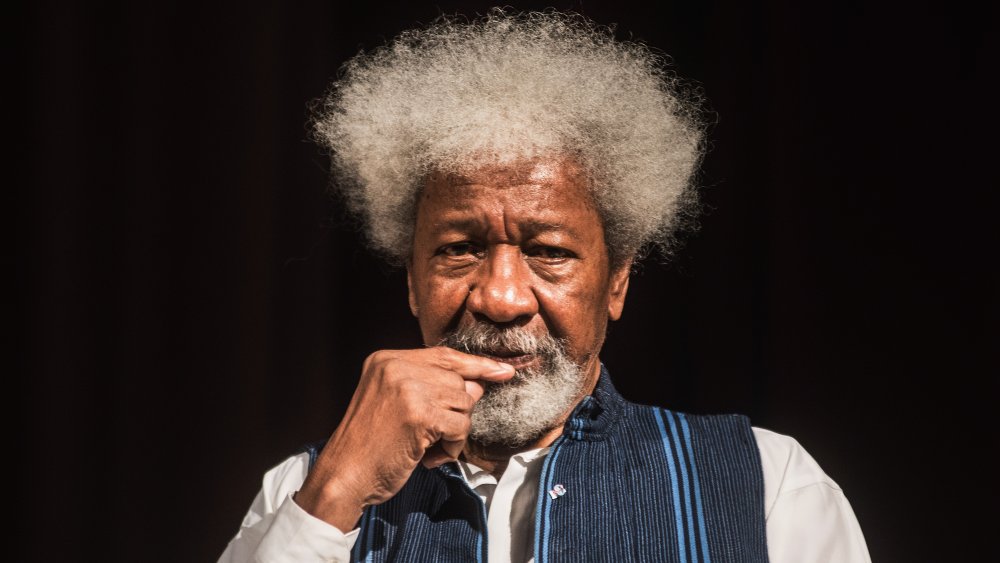

Writing to survive in prison

Wole Soyinka is a Nigerian writer who was imprisoned during the Nigerian civil war that began in 1967. Soyinka was arrested in the first year of the war after writing an article that appealed for a ceasefire. Reuters reports that Soyinka spent almost two years in solitary confinement as a political prisoner. During this time, he composed poems on tissue paper and would later include them in The Man Died: Prison Notes, which compiled his prison poetry and recounted his imprisoned experiences.

Per the Leeds University Library Blog, the prison poems almost never existed. For a majority of his imprisonment, Soyinka was denied anything to write with so he memorized the short verses he'd compose. Eventually, he found some scraps and was able to write the poems down. His poems offer a glimpse into the time spent in solitary confinement; "They hold/ Siege against humanity/ And Truth/ Employing time to drill through to his sanity."

When the civil war ended in 1969, Soyinka was released. However, he ended up leaving the country in exile on several occasions as a result of his continued challenges to the military rule. According to The Atlantic, after Soyinka had his passport confiscated in the 1990s, he managed to sneak out of Nigeria and find asylum in the United States. The dictator at the time, Sani Abacha, tried and convicted Soyinka of treason in absentia and sentenced him to death. Soyinka wouldn't return to Nigeria until after Abacha's death in 1998.

A lifetime in prison

George Jackson was only 18 when he was convicted in 1961 on questionable evidence. According to Soledad Brother: The Prison Letters of George Jackson, he'd later write that he "was captured and brought to prison when I was 18 years old because I couldn't adjust." Because of his prior arrests, Jackson was sentenced to between one year and life in prison.

During his time at San Quentin, Jackson wrote and read frequently. He read Engels, Trotsky, and Mao, and wrote about the experience of prisoners. His writings tapped into the consciousness of a marginalized community; "They live like there was no tomorrow. And for most of them there isn't." After his death, they were compiled in Soledad Brother: The Prison Letters of George Jackson.

In 1969, Jackson was transferred to Soledad Prison. There, Jackson spent over seven and a half years in solitary confinement. Writing became a way to escape the dehumanizing experience of prison in addition to shedding a light on it. At Soledad Prison, Jackson became infamous when he and two other imprisoned people, Fleeta Drumgo and John Cluchette, were falsely accused of killing a white prison guard.

As reported by The Paris Review, on August 21, 1971, Jackson reportedly pulled a gun on the prison guards, tried to escape, and died in the ensuing gunfire.

Prison poetry composed without paper

Out of the many stories that came out of the Russian gulags, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn's Gulag Archipelago is probably the most well-known. But there were dozens of different camps with thousands of different people and Kolyma Tales by Varlam Shalamov offers a literary glimpse into the lives destroyed by a farcical penal system.

According to The Varlam Shalamov Website, Shalamov was first arrested in 1929 when he was caught printing pamphlets titled "Lenin's testament" during a raid of an underground print shop. After spending three years in a labor camp by the North Urals, he lived and worked in Moscow as a writer and journalist until his arrest on January 13th, 1937 for counterrevolutionary Trotskyist activities. This time, he was sentenced to the prison camps in the Kolyma River basin in Magadan at the eastern-most end of Russia.

Shalamov spent almost 17 years in the labor camps, during which time he composed poetry in his head. Around 1949, when he began working as a medical assistant, Shalamov was allowed minor privileges and was able to find scraps of paper and pencil stubs with which to record his poetry.

These poems and Shalamov's experiences came together to become Kolyma Tales, a series of stories that recount tales of death and dying through a lyricism that insists on survival. The Financial Times cites that Shalamov compiled the text in the 1950s but wasn't able to smuggle it out of Russia until the late 1960s.

Telling stories over and over again in prison

Born on February 20, 1925, Pramoedya Ananta Toer was one of the most prominent prose writers in Indonesia after its independence. In 1945, after Indonesia revolted against Dutch colonial rule, Pramoedya began working on an Indonesian-language magazine until his arrest in 1947. This was his first experience with writing in prison and his first novel "Perburuan (The Fugitive)" came out of the two years that he spent incarcerated.

Pramoedya was arrested again in 1965 after President Suharto rose to power and ordered the detention of his opponents without trials. According to Culture Trip, Pramoedya's increasingly critical political writings led to him being targeted by the government, and during his imprisonment, he was explicitly denied any writing supplies.

Undaunted, Pramoedya began composing an epic tetralogy orally, reciting the story to the people he was imprisoned with. The works became known as "The Buru Quartet," following the protagonist Minke, a Javanese boy who attempts to work through the complicated process that is the anti-colonialist struggle during the birth of nationalism in Indonesia. Per PBS, once Pramoedya was allowed to write, the other imprisoned people would take on his labor duties so that he had more time to write.

Pramoedya wrote other books in addition to the tetralogy during his imprisonment, but when riverboat men and priests were smuggling out his texts, they were caught and the books were destroyed by prison guards. He was released into house arrest until 1992.

Attacking oppressive systems with an eyebrow pencil

Dr. Nawāl al-Saʿdāwī, also spelled Dr. Nawal El Saadawi, has spent her life advocating for women's political and sexual rights in Egypt. Trained as a physician, al-Saʿdāwī worked at Cairo University and the Egyptian ministry of health from 1955 to 1965.

However, her work was repeatedly suppressed. The magazine she founded, Health, was shut down by Egyptian authorities in 1973. The previous year, in 1972, al-Saʿdāwī was also expelled from her job in the ministry of health because of her book Al-marʾah wa al-jins (Women and Sex).

According to the Index on Censorship, al-Saʿdāwī was one of over 1,000 people who were arrested on September 6, 1981 and held without charge. According to Time, she was reportedly arrested for her outspoken views, which were considered "crimes against the state."

Al-Saʿdāwī was held for almost a year, and during a two-month span, she wrote about her experiences with a smuggled eyebrow pencil and toilet paper. She was finally released, her experience became immortalized in her 1983 text Memoirs from the Women's Prison. Al-Saʿdāwī continues to this day to use her writing to condemn repressive systems and has written that "There is no power in the world that can strip my writings from me." Al-Saʿdāwī continues to write and fight for women's rights.

Folding together a story in solitary

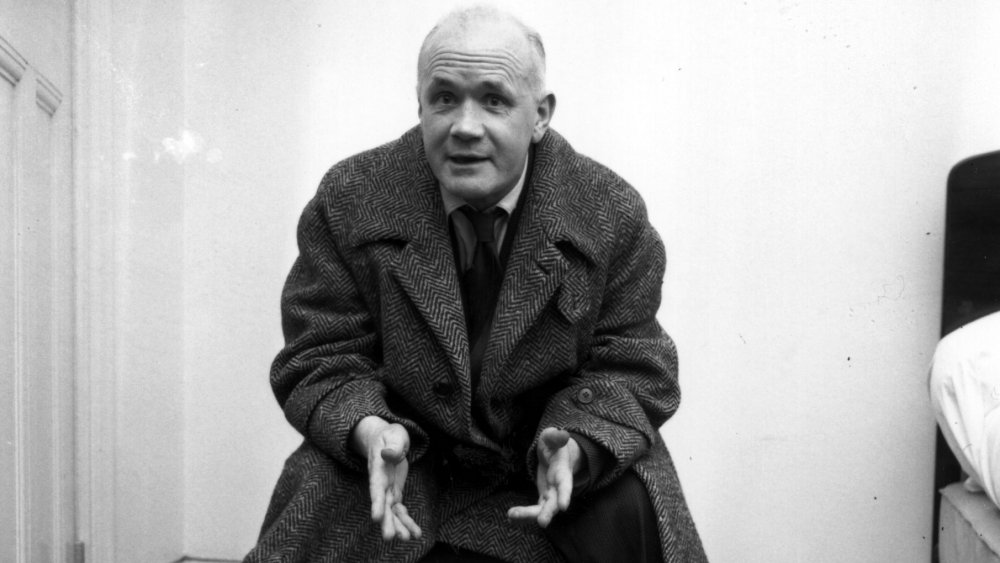

Jean Genet's book Our Lady of the Flowers was published anonymously in 1943 when it first came out. It wouldn't be published under his name until the following year.

Written while Genet was imprisoned at Paris' Prison de la Santé for a string of burglaries, Our Lady of the Flowers tells a sexually explicit tale of the Parisian underworld while the narrator informs the reader that many of the stories are told in order to assist with his self-pleasure while in prison.

The early draft of Our Lady of the Flowers perished early. According to the introduction written by Jean-Paul Sartre, the drafts were written on brown paper that was to be made into bags by imprisoned people. Once, the manuscript was found by guards and it was burned. According to The Paris Review, Genet was sentenced to solitary confinement for three days as punishment for misusing the paper "for literary masterpieces." Undeterred, Genet rewrote his masterpiece and was able to smuggle it out with him upon leaving the prison.

Leaving proof of what happened

Born on July 23, 1983 in Kurdistan, Behrouz Boochani fled his native Iran in 2013, after his work as the editor of Werya, a Kurdish social and political magazine, caught the attention of the authorities. Boochani was repeatedly arrested and interrogated and on February 17, 2013, Sepah raided Werya's offices in Ilam and arrested several of his colleagues. Boochani was in Tehran at the time so he was able to avoid arrest, but he knew that his existence in Iran was precarious.

According to The Guardian, Boochani sought asylum in Australia, arriving in July 2013, and was taken to the Manus Island detention center in Papua New Guinea. He was held there for almost six years with little-to-no prospect of being released other than through deportation. While there, Boochani witnessed fellow imprisoned people murdered by guards and severe mental abuse inflicted on asylum seekers at the detention center.

According to Australian Book Review, Boochani wrote his autobiography, No Friend But the Mountains: Writing from Manus Prison, one text message at a time in Farsi, sent to translator and refugee advocate Moones Mansoubi. Boochani was finally granted asylum in New Zealand in 2020, but over 400 asylum seekers remain imprisoned at Australia's two offshore detention centers on the islands of Nauru and Manus.

A high security woman

Born on October 5, 1955, Susan Rosenberg became active in protesting early on. According to Politico, by age 11 she was attending anti-war and civil rights demonstrations with her parents and during her college years, she supported Vietnamese women's struggle against U.S. imperialism. In 1978, Rosenberg and a handful of other women including Marilyn Buck and Judy Clark formed a far-left organization called May 19th, also known as M19.

According to Smithsonian Magazine, M19 went from making posters and picketing to abetting prison breaks and robbing armored trucks. By 1983, M19 was setting off explosives. Between 1983 and 1984, M19 set off bombs in the north wing of the U.S. Capitol, an FBI office, the South African consulate in New York, the Israel Aircraft Industries building, and D.C.'s Navy Yard and Fort McNair. The bombings were always preceded by a warning call and proceeded by a pre-recorded anti-imperialist message.

Rosenberg was ultimately arrested in 1984 for a crime that she claims she wasn't involved with. She was one of the first imprisoned people at Lexington Prison, America's second high-security prison, where she ended up spending 16 years until her pardon in 2001. According to P.E.N., during her time in prison, she received an MFA from Antioch University and went on to receive four P.E.N. writing awards while incarcerated. Some 10 years after her release, she compiled her experiences and writing in An American Radical: A Political Prisoner in My Own Country.